Funny Louis and Happy Jack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Atchafalaya Basin

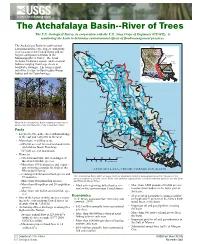

7KH$WFKDIDOD\D%DVLQ5LYHURI7UHHV The U.S. Geological Survey, in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), is monitoring the basin to determine environmental effects of flood-management practices. The Atchafalaya Basin in south-central Louisiana includes the largest contiguous river swamp in the United States and the largest contiguous wetlands in the Mississippi River Valley. The basin includes 10 distinct aquatic and terrestrial habitats ranging from large rivers to backwater swamps. The basin is most noted for its cypress-tupelo gum swamp habitat and its Cajun heritage. Water in the Atchafalaya Basin originates from one or more of the distributaries of the Atchafalaya River. Facts • Located between the cities of Baton Rouge to the east and Lafayette to the west. • More than 1.4 million acres: --885,000 acres of forested wetlands in the Atchafalaya Basin Floodway. --517,000 acres of marshland. • Home to: --9 Federal and State listed endangered/ threatened wildlife species. --More than 170 bird species and impor- tant wintering grounds for birds of the Mississippi Flyway. --6 endangered/threatened bird species and The Atchafalaya Basin offers an opportunity to implement adaptive management practices because of the 29 rookeries. general support of private, local, State, and national organizations and governmental agencies for the State --More than 40 mammalian species. and Federal Master Plans. --More than 40 reptilian and 20 amphibian • Most active-growing delta (land accre- • More than 1,000 pounds of finfish per acre species. tion) in the conterminous United States. in some water bodies in the lower part of --More than 100 finfish and shellfish spe- the basin. -

Landforms & Bodies of Water

Name Date Landforms & Bodies of Water - Vocab Cards hill noun a raised area of land smaller than a mountain. We rode our bikes up and down the grassy hill. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: island noun a piece of land surrounded by water on all sides. Marissa's family took a vacation on an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: 1 lake noun a large body of fresh or salt water that has land all around it. The lake freezes in the wintertime and we go ice skating on it. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: landform noun any of the earth's physical features, such as a hill or valley, that have been formed by natural forces of movement or erosion. I love canyons and plains, but glaciers are my favorite landform. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: 2 mountain noun a land mass with great height and steep sides. It is much higher than a hill. Someday I'm going to hike and climb that tall, steep mountain. Synonyms: peak Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: ocean noun a part of the large body of salt water that covers most of the earth's surface. -

Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed As Part of Sherburne Complex

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Atchafalaya National Wildlife Refuge Managed as part of Sherburne Complex Tom Carlisle This basin contains over one-half million acres of hardwood swamps, lakes and bayous, and is larger than the vast Okefenokee Swamp of Georgia and Florida. It is an immense This blue goose, natural floodplain of the Atchafalaya designed by J.N. River, which flows for 140 miles south “Ding” Darling, from its parting from the Mississippi has become the River to the Gulf of Mexico. symbol of the National Wildlife The fish and wildlife resources Refuge System. of the Atchafalaya River Basin are exceptional. The basin’s dense bottomland hardwoods, cypress- tupelo swamps, overflow lakes, and meandering bayous provide a tremendous diversity of habitat for many species of fish and wildlife. Ecologists rank the basin as one of the most productive wildlife areas in North America. The basin also supports an extremely productive sport and commercial fishery, and provides unique recreational opportunities to hundreds of thousands of Americans each year. Wildlife Every year, thousands of migratory waterfowl winter in the overflow swamps and lakes of the basin, located at the southern end of the great Mississippi Flyway. The lakes of the lower basin support one of the largest wintering concentrations of canvasbacks in Louisiana. The basin’s wooded wetlands also provide vital nesting habitat for wood ducks, and support the nation’s largest concentration of American America’s Great River Swamp woodcock. More than 300 species of Deep in the heart of Cajun Country, resident and migratory birds use the basin, including a large assortment at the southern end of the Lower of diving and wading birds such as egrets, herons, ibises, and anhingas. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

Moving Water Shapes Land

KEY CONCEPT Moving water shapes land. BEFORE, you learned NOW, you will learn •Erosion is the movement of • How moving water shapes rock and soil Earth’s surface • Gravity causes mass movements • How water moving under- of rock and soil ground forms caves and other features VOCABULARY EXPLORE Divides drainage basin p. 579 How do divides work? divide p. 579 floodplain p. 580 PROCEDURE MATERIALS alluvial fan p. 581 •sheet of paper 1 Fold the sheet of paper in thirds and tape delta p. 581 • tape it as shown to make a “ridge.” sinkhole p. 583 •paper clips 2 Drop the paper clips one at a time directly on top of the ridge from a height of about 30 cm. Observe what happens and record your observations. WHAT DO YOU THINK? How might the paper clips be similar to water falling on a ridge? Streams shape Earth’s surface. If you look at a river or stream, you may be able to notice something about the land around it. The land is higher than the river. If a river is running through a steep valley, you can easily see that the river is the low point. But even in very flat places, the land is sloping down to the river, which is itself running downhill in a low path through the land. NOTE-TAKING STRATEGY Running water is the major force shaping the landscape over most A main idea and detail of Earth. From the broad, flat land around the lower Mississippi River notes chart would be a good strategy to use for to the steep mountain valleys of the Himalayas, water running downhill taking notes about streams changes the land. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Reports IGERT 2013 Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science Micah Bennett Southern Illinois University Carbondale Kelley Fritz Southern Illinois University Carbondale Anne Hayden-Lesmeister Southern Illinois University Carbondale Justin Kozak Southern Illinois University Carbondale Aaron Nickolotsky Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports A report in fulfillment of the NSF IGERT Program requirements. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 0903510. Recommended Citation Bennett, Micah; Fritz, Kelley; Hayden-Lesmeister, Anne; Kozak, Justin; and Nickolotsky, Aaron, "Multi-Use Management in the Atchafalaya River Basin: Research at the Confluence of Public Policy and Ecosystem Science" (2013). Reports. Paper 2. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/igert_reports/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IGERT at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MULTI-USE MANAGEMENT IN THE ATCHAFALAYA RIVER BASIN: RESEARCH AT THE CONFLUENCE OF PUBLIC POLICY AND ECOSYSTEM SCIENCE BY MICAH BENNETT, KELLEY FRITZ, ANNE HAYDEN-LESMEISTER, JUSTIN KOZAK, AND AARON NICKOLOTSKY SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CARBONDALE NSF IGERT PROGRAM IN WATERSHED SCIENCE AND POLICY A report -

Overview of the Mississippi River & Tributaries (Mr&T)

1 OVERVIEW OF THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER & TRIBUTARIES (MR&T) - ATCHAFALAYA BASIN PROJECT 237 217 200 80 252 237 217 200 119 174 237 217 200 27 .59 255 0 163 131 239 110 112 62 102 130 Port255 Of0 Morgan163 City132 –65 Stakeholder135 92 Meeting102 56 120 255 0 163 122 53 120 56 130 48 111 Durund Elzey Assistance Deputy District Engineer (ADPM) US Army Corps of Engineers New Orleans District 11 February 2019 2 TOPICS OF DISCUSSION • Passing the MR&T Project Design Flood • The Jadwin Plan • The Morganza Floodway • The Old River Control Complex • MR&T Atchafalaya Basin Flood Control Project • Atchafalaya Basin Levee Construction • Atchafalaya Basin O&M • Atchafalaya River Dredging • The Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System (ABFS) Project • Sedimentation Issues • Path Forward 3 THE FLOOD OF 1927 Flood Control Act of 1928 4 and the Jadwin Plan The Morganza Floodway 5 6 Old River Control Structures Authorized 1973 Flood . The Low Sill Control Structure was undermined and the Wing Wall failed . The Old River Overbank Control Structure and the Morganza Control Structure were opened to relieve stress on the Low Sill Control Structure . Due to severe damage to the Low Sill Control Structure, USACE recommended construction of the Auxiliary Control Structure, which was completed in 1986 Morganza Control Structure Operated for First Time View of Old River Control Complex Old River Lock Auxiliary Control Structure Low Sill Control Structure Overbank Control Structure S.A. Murray Hydro 9 The Flood of 2011 10 Extent of 1927 Flood (in Blue) Versus 2011 Flood (in Green) Passing the Project Design Flood 11 The MR&T Atchafalaya Basin Project The MR&T Atchafalaya Basin Project Major Components • 451 Miles of Levees and Floodwalls • 4 Navigation Locks . -

1698: a Prelude to Louisiana

1698: A PRELUDE TO LOUISIANA Forests of odd-looking trees. Marshes and prairies of waving grasses. Water everywhere… lakes, bayous, a spectacular river, and soggy swamps. Insects galore. Half-naked Indians with strange customs. Strange foods. Unpredictable, unmerciful weather. LaSalle had passed through this landscape in 1682 and claimed it all for France. None of his countrymen, though, made it back until an expedition under the LeMoyne brothers of Canada arrived in 1699. This is the prelude to what they would find as they paddled and slogged through the land that would eventually become New Orleans. It was largely due to these very elements - good and bad – that the City of New Orleans is what it is today. Understanding the original inhabitants and the basic geography of this area is key to understanding how New Orleans came into existence in the first place, and why it is still such a dynamic and economically important city today. The Native Americans By 1650, Spain, Britain, and France had divvied up North America among themselves. No thought, of course, was given to the people who actually lived here. After all, they had no guns, were often migratory, living off the bounty of the earth in cooperation with the needs and requirements of the land. Besides, there were not a whole lot of them. To the European mind, therefore, the American continents were vast, empty lands upon which to plant their civilization. It appears that the French, as opposed to the other Powers, saw the natives as a bit more than half-naked savages. -

Louisiana's Waterways

Section22 Lagniappe Louisiana’s The Gulf Intracoastal Waterways Waterway is part of the larger Intracoastal Waterway, which stretches some three As you read, look for: thousand miles along the • Louisiana’s major rivers and lakes, and U.S. Atlantic coast from • vocabulary terms navigable and bayou. Boston, Massachusetts, to Key West, Florida, and Louisiana’s waterways define its geography. Water is not only the dominant fea- along the Gulf of Mexico ture of Louisiana’s environment, but it has shaped the state’s physical landscape. coast from Apalachee Bay, in northwest Florida, to Brownsville, Texas, on the Rio Grande. Right: The Native Americans called the Ouachita River “the river of sparkling silver water.” Terrain: Physical features of an area of land 40 Chapter 2 Louisiana’s Geography: Rivers and Regions The largest body of water affecting Louisiana is the Gulf of Mexico. The Map 5 Mississippi River ends its long journey in the Gulf’s warm waters. The changing Mississippi River has formed the terrain of the state. Louisiana’s Louisiana has almost 5,000 miles of navigable rivers, bayous, creeks, and Rivers and Lakes canals. (Navigable means the water is deep enough for safe travel by boat.) One waterway is part of a protected water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Map Skill: In what direction Gulf of Mexico. The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway extends more than 1,100 miles does the Calcasieu River from Florida’s Panhandle to Brownsville, Texas. This system of rivers, bays, and flow? manmade canals provides a safe channel for ships, fishing boats, and pleasure craft. -

City of Covington Flood Response Newsletter Fall 2018

CITY OF COVINGTON FLOOD RESPONSE NEWSLETTER FALL 2018 FLOODING IS A KNOWN RANKING HISTORIC CRESTS RECENT CRESTS HAZARD IN COVINGTON 1 19.20 ft on 03/12/2016 9.31 ft on 08/13/2016 Flash flooding, riverine flooding, and rainfall-induced 2 17.10 ft on 01/21/1993 19.20 ft on 03/12/2016 flooding are the most common flood types affecting the City of Covington. Recorded incidents include flash 3 16.63 ft on 07/01/2003 13.20 ft on 02/24/2016 floods and urban small-stream floods. Floods tend to be concentrated in low-lying areas near rivers and 4 16.50 ft on 02/22/1961 6.52 ft on 5/22/2015 streams with damage ranging from negligible cost to millions of dollars. Significant flooding due to high 5 16.50 ft on 06/11/2001 10.16 ft on 06/01/2014 intensity precipitation occurred in November 1979, May and June 1983, May 1995, during Hurricane Katrina in 6 15.39 ft on 08/30/2012 11.55 ft on 01/12/2013 August 2005, and most recently in March 2016. 7 14.20 ft on 01/07/1998 15.39 ft on 08/30/2012 Nested at the confluence of the Tchefuncte River and the Bogue Falaya (which captures the Abita River), the City of Covington is prone to riverine flooding, meaning 8 14.00 ft on 10/04/2002 9.8 ft on 03/27/2009 your house is in a flood-prone area. If you think you may be susceptible to flooding, call (985) 898-4725 to 9 13.80 ft on 09/27/2002 13.26 ft on 09/02/2008 learn more about the flood hazard for your property! 10 13.26 ft on 09/02/2008 9.10 ft on 12/31/2006 11 13.20 ft on 02/24/2016 5.55 ft on 04/30/2006 12 12.40 ft on 04/03/1998 16.63 ft on 07/01/2003 13 11.70 ft on 05/10/1995 3.65 ft on 01/01/2003 14 11.55 ft on 01/12/2013 9.09 ft on 12/25/2002 15 10.34 ft on 08/07/2002 14.00 ft on 10/04/2002 ENSURE YOU ARE NOT A VICTIM Because you are located within a floodplain, ask your insurance agent whether you are covered for flood damage. -

Louisiana Natural and Scenic Rivers' Descriptions

Louisiana Natural and Scenic Rivers' Descriptions (1) Pushepatapa Creek - Washington - From where East Fork and West Fork join near state line to where it breaks up prior to its entrance into the Pearl River. (2) Bogue Chitto River - Washington, St. Tammany - From the Louisiana-Mississippi state line to its entrance into the Pearl River Navigation Canal. (3) Tchefuncte River and its tributaries - Washington, Tangipahoa, St. Tammany - From its origin in Tangipahoa Parish to its juncture with the Bogue Falaya River. (4) Tangipahoa River - Tangipahoa - From the Louisiana-Mississippi state line to the I-12 crossing. (5) (Blank) (6) Tickfaw River - St. Helena - From the Louisiana-Mississippi state line to La. Hwy. 42. (7) Amite River-East Feliciana-From the Louisiana-Mississippi state line to the permanent pool level of the Darlington Reservoir; and from the Darlington Reservoir Dam to La. Hwy. 37; provided that the portion of the Amite River from the Louisiana-Mississippi state line to La. Hwy. 37 shall remain within the Natural and Scenic Rivers System until the issuance of a permit by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issued pursuant to 33 U.S.C. 1344 and 33 C.F.R. 232; provided, that if the Darlington Reservoir and dam are not approved and funded no later than September 1, 1997, the portion of the Amite River within the Natural and Scenic Rivers System shall be as follows: From the Louisiana-Mississippi state line to La. Hwy. 37. (8) Comite River - East Feliciana, East Baton Rouge - From the Wilson-Clinton Hwy. in East Feliciana Parish to the entrance of White Bayou in East Baton Rouge Parish.