Effects of a Shallow Flood Shoal and Friction on Hydrodynamics of A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sedimentary Processes and Geomorphic History of Wreck Shoal, an Oyster Reef of the James River, Virginia

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 THE SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES AND GEOMORPHIC HISTORY OF WRECK SHOAL, AN OYSTER REEF OF THE JAMES RIVER, VIRGINIA Joseph T. DeAlteris College of William and Mary - Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation DeAlteris, Joseph T., "THE SEDIMENTARY PROCESSES AND GEOMORPHIC HISTORY OF WRECK SHOAL, AN OYSTER REEF OF THE JAMES RIVER, VIRGINIA" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539616626. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25773/v5-af3n-wf26 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

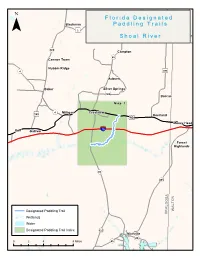

Florida Designated Paddling Trails Shoal River

F ll oCR)"r 6i0i2d a D e s ii g n a tt e d Blackman P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll s C)"R 2 ¯ )"2 C)"R 2 S h o a ll R ii v e r CR)" 147 189 «¬ Campton 85 Cannon Town «¬ Nubbin Ridge «¬4 )"393 Auburn Baker Silver Springs 188 )" Dorcas M a p 1 «¬4 Milligan Crestview )"189 Deerland ¤£90 Mossy Head 10 Holt Galliver ¨¦§ Forest Highlands «¬85 «¬285 A N S O O T O L L A A W Designated Paddling Trail K O Wetlands Water Designated Paddling Trail Index «¬123 Niceville «¬20 0 2 4 8 Miles «¬85 S h o a ll R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 1 )"188 STILLWELL BLVD ¯ NO B RTH AVE R V A A C L K L I N E Y S R T D F Crestview A I L R L C O H Y I L D D S 90 R T CH ¤£ D ES NU T A Þ VE !| 2)"80A Access Point 1: Ray Barnes Boat Ramp/US 90 N: 30.7535 W: -86.5099 OKALOOSA ¨¦§10 JOHN K ING RD L I 85 V ¬ E « O Okaloosa County Shoal River A K Land Acquisition PJ AD C AMS PKWY H U R C H R D A NT Choctawhatchee IOC Choctawhatchee H R Nat'l Forest D Nat'l Forest !|*IÞ Access Point 2: Bill Duggan Jr Park/SR 85 N: 30.6976 W: -86.5712 Shoal River Paddling Trail Eglin Air Force Base !| Canoe/Kayak Launch *I Restrooms Þ Potable Water Florida Conservation Lands 0 0.5 1 2 Miles Wetlands Shoal River Paddling Trail Guide The Waterway A nature photographer’s dream, the shallow, gold-tinted Shoal River threads through a northwest Florida wilderness of high sandy hills, broad sandbars perfect for rest stops, and floodplain forest. -

A Wader Survey of South Gippsland Beaches by WILLIAM A

48 DAVIS, A Wader Survey [ Bird Watcher A Wader Survey of South Gippsland Beaches By WILLIAM A. DAVIS, Melbourne. On February 23, 24 and 25, 1963, a trip was undertaken by four members of the Bird Observers Club in an endeavour to ascertain the wader potentiality of some of the remote South Gippsland beaches. Habitats and bird populations at each locality were noted, and all the birds S€~ on the trip were recorded. Lack of time allowed only a brief survey to be made but, in spite of this, 117 species were positively identified. The members participating in the survey were F. T. H . Smith, F. Fehrer, H . Beste and the writer. At the present time wader haunts within close proximity to Melbourne are regularly visited each season. However, there remain vast areas of suitable habitat more distant from the metro polis which, due to their remoteness, have received little or no attention from observers. The territory covered by our trip extended from Shallow Inlet on the western side of Wilson's Promontory to Jack Smith's Lake, approximately 20 miles west of Seaspray on the Ninety Mile Beach. The localities visited were as follows: Shallow Inlet: A large tidal inlet comprising extensive sand and mud-flats, ocean beach, and typical coastal bushland consisting essentially of banksias, messmate, manna gums, heathlands and open paddocks. This was possibly the best area that we encountered for general bird observation, that also had good wader potentiality although, at the time of our visit, there was a noticeable absence of the small waders. Both the east and west sides of the inlet were examined and 69 species were recorded in six hours. -

Sandbridge Beach FONSI

FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT Issuance of a Negotiated Agreement for Use of Outer Continental Shelf Sand from Sandbridge Shoal in the Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control and Hurricane Protection Project Virginia Beach, Virginia Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Council on Environmental Quality regulations implementing NEPA (40 CFR 1500-1508) and Department of the Interior (DOI) regulations implementing NEPA (43 CFR 46), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) prepared an environmental assessment (EA) to determine whether the issuance of a negotiated agreement for the use of Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) sand from Sandbridge Shoal Borrow Areas A and B for the Sandbridge Beach Erosion Control and Hurricane Protection Project near Virginia Beach, VA would have a significant effect on the human environment and whether an environmental impact statement (EIS) should be prepared. Several NEPA documents evaluating impacts of the project have been previously prepared by both the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and BOEM. The USACE described the affected environment, evaluated potential environmental impacts (initial construction and nourishment events), and considered alternatives to the proposed action in a 2009 EA. This EA was subsequently updated and adopted by BOEM in 2012 in association with the most recent 2013 Sandbridge nourishment effort (BOEM 2012). Prior to this, BOEM (previously Minerals Management Service [MMS]) was a cooperating agency on several EAs for previous projects (MMS 1997; MMS 2001; MMS 2006). This current EA, prepared by BOEM, supplements and summarizes the aforementioned 2012 analysis. BOEM has reviewed all prior analyses, supplemented additional information as needed, and determined that the potential impacts of the current proposed action have been adequately addressed. -

Landforms & Bodies of Water

Name Date Landforms & Bodies of Water - Vocab Cards hill noun a raised area of land smaller than a mountain. We rode our bikes up and down the grassy hill. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: island noun a piece of land surrounded by water on all sides. Marissa's family took a vacation on an island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: 1 lake noun a large body of fresh or salt water that has land all around it. The lake freezes in the wintertime and we go ice skating on it. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: landform noun any of the earth's physical features, such as a hill or valley, that have been formed by natural forces of movement or erosion. I love canyons and plains, but glaciers are my favorite landform. Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: 2 mountain noun a land mass with great height and steep sides. It is much higher than a hill. Someday I'm going to hike and climb that tall, steep mountain. Synonyms: peak Use this word in a sentence or give an example Draw this vocab word or an example of it: to show you understand its meaning: ocean noun a part of the large body of salt water that covers most of the earth's surface. -

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel Columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz

Our Ocean Backyard –– Santa Cruz Sentinel columns by Gary Griggs, Director, Institute of Marine Sciences, UC Santa Cruz. #45 January 2, 2010 Why Monterey Submarine Canyon? Monterey Submarine Canyon forms a deep gash beneath the waters of Monterey Bay. At the risk of beating submarine canyons to death, I’m going to try to wrap up this discussion with some final thoughts on why we have one of the world’s largest submarine canyons in our backyard. Monterey Submarine Canyon has been known for over a century, and as with other offshore drainage systems, there has been considerable speculation over the years as to why we have this huge chasm cutting across the seafloor. Most submarine canyons align with river systems, but Elkhorn Slough hardly provides an adequate onshore source for such a massive feature. We do know that prior to 1910 the Salinas River discharged six miles north of its present mouth into Elkhorn Slough, closer to the head of Monterey Submarine Canyons. But even the Salinas River is not of the scale we would expect for an offshore feature as large as the Grand Canyon. Over 50 years ago, two geologists discovered the presence of a deep buried inland canyon beneath the Santa Cruz Mountains from oil company drill holes. This combined with other geological and geophysical observations strongly suggested that this canyon was eroded by an ancient river drainage system that played a critical role in the initial formation of the Monterey Submarine Canyon. This buried canyon, named Pajaro Gorge by some, was the route that the drainage from California’s vast Central Valley followed to the ocean for million of years. -

Wetland Loss in the Lower Galveston Bay Watershed

Galveston Bay Wetland Permit and Mitigation Assessment Lisa Gonzalez Dr. Erin Kinney Dr. John Jacob Marissa Llosa Transportation Stream & Wetland Mitigation Peer Exchange – June 5-6, 2018 Galveston Bay Watershed ~24,000 square miles ~Half of Texas’ population of 28M TXDOT Districts Beaumont Houston Population Growth 213 % 59 % 65 % * 119 % * 54 % 239 % 106 % 89 % % Change in Population 1990 to 2017 Data Source: U.S. Census, *Texas Demographic Center Population Projection Regional Habitat H-GAC Eco-Logical Map; Wetland Mitigation Opportunities white paper, 2014 Regional Land Cover Change; 1996-2010 • Growth in impervious (107K acres) & developed (254K acres) areas • Wetland net change -54K acres NLDC, NOAA C-CAP Coastal Bottomlands and Blue Elbow Mitigation Banks Mitigation Bank Mitigation Bank HUC8 ORMII Permits ORMII Permits Galveston Bay Mitigation Banks TCWP Ground-truth Wetland Mitigation Assessment • 17 sites: 4 permit mitigation sites not accessible, leaving 13 permits for site review (8 PRM, 5 MB). • Assessment criteria based on three-fold definition of a wetland (Tiner, 1989): – Hydrophytic vegetation (partially or completely submerged in water), – Evidence of hydrology, – Soil indicators consistent with wetland hydrology. • Conservative assessment: – Success: “reasonably wet” with recognizable wetland plants and hydric soils. – Failure: substandard compensatory mitigation site with a lack of any evidence for wetland mitigation TCWP Ground-truth Wetland Mitigation Assessment • Minimum 5% of the total mitigation site inventoried. • Plots (10 m x 10 m) representatively within the tract. • Plant species presence and percent cover assessed. • Cover of various biotic and abiotic surface materials collected in each plot. • Comprehensive list of species compiled. • Pictures of the site and the sample plot taken along with any notable site features. -

A Nonlinear Relationship Between Marsh Size and Sediment Trapping Capacity Compromises Salt Marshes’ Stability Carmine Donatelli1*, Xiaohe Zhang2*, Neil K

https://doi.org/10.1130/G47131.1 Manuscript received 22 October 2019 Revised manuscript received 9 March 2020 Manuscript accepted 26 April 2020 © 2020 The Authors. Gold Open Access: This paper is published under the terms of the CC-BY license. Published online 10 June 2020 A nonlinear relationship between marsh size and sediment trapping capacity compromises salt marshes’ stability Carmine Donatelli1*, Xiaohe Zhang2*, Neil K. Ganju3, Alfredo L. Aretxabaleta3, Sergio Fagherazzi2† and Nicoletta Leonardi1† 1 Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Liverpool, Roxby Building, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZT, UK 2 Department of Earth Sciences, Boston University, 675 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA 3 Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA ABSTRACT tidal flats to keep pace with sea-level rise (Mari- Global assessments predict the impact of sea-level rise on salt marshes with present-day otti and Fagherazzi, 2010). levels of sediment supply from rivers and the coastal ocean. However, these assessments do Regional effects are crucial when evaluating not consider that variations in marsh extent and the related reconfiguration of intertidal area coastal interventions under the management of affect local sediment dynamics, ultimately controlling the fate of the marshes themselves. multiple agencies. Though many studies have We conducted a meta-analysis of six bays along the United States East Coast to show that focused on local marsh dynamics, less atten- a reduction in the current salt marsh area decreases the sediment availability in estuarine tion has been paid to how changes in marsh systems through changes in regional-scale hydrodynamics. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

Moving Water Shapes Land

KEY CONCEPT Moving water shapes land. BEFORE, you learned NOW, you will learn •Erosion is the movement of • How moving water shapes rock and soil Earth’s surface • Gravity causes mass movements • How water moving under- of rock and soil ground forms caves and other features VOCABULARY EXPLORE Divides drainage basin p. 579 How do divides work? divide p. 579 floodplain p. 580 PROCEDURE MATERIALS alluvial fan p. 581 •sheet of paper 1 Fold the sheet of paper in thirds and tape delta p. 581 • tape it as shown to make a “ridge.” sinkhole p. 583 •paper clips 2 Drop the paper clips one at a time directly on top of the ridge from a height of about 30 cm. Observe what happens and record your observations. WHAT DO YOU THINK? How might the paper clips be similar to water falling on a ridge? Streams shape Earth’s surface. If you look at a river or stream, you may be able to notice something about the land around it. The land is higher than the river. If a river is running through a steep valley, you can easily see that the river is the low point. But even in very flat places, the land is sloping down to the river, which is itself running downhill in a low path through the land. NOTE-TAKING STRATEGY Running water is the major force shaping the landscape over most A main idea and detail of Earth. From the broad, flat land around the lower Mississippi River notes chart would be a good strategy to use for to the steep mountain valleys of the Himalayas, water running downhill taking notes about streams changes the land. -

Short Creek and Shoal Creek in the Spring River Watershed Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus

NEOSHO BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody / Assessment Unit: Short Creek and Shoal Creek in the Spring River Watershed Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Spring Counties: Cherokee HUC8: 11070207 HUC10(12): 08(06) & 09(04) Ecoregion: Ozark Highlands, Springfield Plateau (39a) Drainage Area: Shoal Creek = approximately 10.1 square miles in Kansas Short Creek = approximately 5.94 square miles in Kansas Water Quality Limited Segments Covered Under this TMDL: Station Main Stem Segment Tributary Station SC570 Short Creek (881) Station SC212 Shoal Creek (2) Unnamed Stream (886) 2008, 2010, 2012 & 2014 303(d) Listings: Kansas Stream segments monitored by stations SC212 on Short Creek and SC570 on Shoal Creek, are cited as impaired by Total Phosphorus (TP) for the Neosho Basin. Impaired Use: Special Aquatic Life, Expected Aquatic Life, Contact Recreation and Domestic Water Supply. Water Quality Criteria: Nutrients – Narratives: The introduction of plant nutrient into surface waters designated for domestic water supply use shall be controlled to prevent interference with the production of drinking water (K.A.R. 28-16-28e(c)(3)(D)). The introduction of plant nutrients into streams, lakes, or wetlands from artificial sources shall be controlled to prevent the accelerated succession or replacement of aquatic biota or the production of undesirable quantities or kinds of aquatic life (K.A.R. 28-16- 28e(c)(2)(A)). The introduction of plant nutrients into surface waters designated for primary or secondary contact recreational use shall be controlled to prevent the development of objectionable concentrations of algae or algal by-products or nuisance growths of submersed, floating, or emergent aquatic vegetation (K.A.R. -

Understanding the Temporal Dynamics of the Wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, Canada

Earth Surface Processes and Landforms EarthTemporal Surf. dynamicsProcess. Landforms of a wandering 30, 1227–1250 river (2005) 1227 Published online 23 June 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/esp.1196 Understanding the temporal dynamics of the wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, Canada Leif M. Burge1* and Michel F. Lapointe2 1 Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University of Toronto, 100 St. George Street, Toronto, Ontario, M5S 3G3, Canada 2 Department of Geography McGill University, 805 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 2K6, Canada *Correspondence to: L. M. Burge, Abstract Department of Geography and Program in Planning, University Wandering rivers are composed of individual anabranches surrounding semi-permanent of Toronto, 100 St. George St., islands, linked by single channel reaches. Wandering rivers are important because they Toronto, M5S 3G3, Canada. provide habitat complexity for aquatic organisms, including salmonids. An anabranch cycle E-mail: [email protected] model was developed from previous literature and field observations to illustrate how anabranches within the wandering pattern change from single to multiple channels and vice versa over a number of decades. The model was used to investigate the temporal dynamics of a wandering river through historical case studies and channel characteristics from field data. The wandering Renous River, New Brunswick, was mapped from aerial photographs (1945, 1965, 1983 and 1999) to determine river pattern statistics and for historical analysis of case studies. Five case studies consisting of a stable single channel, newly formed anabranches, anabranches gaining stability following creation, stable anabranches, and an abandoning anabranch were investigated in detail.