Bolshevik Myth (Diary 1920–22)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passport of St. Petersburg Industrial Zones

The Committee for industrial policy and innovation of St. Petersburg Passport of St. Petersburg industrial zones 3-d edition 2015 Contents 1. Preamble..................................................................................................................................................................2 2. Industrial zones of St. Petersburg............................................................................................................................8 2.1. Area of industrial zones...................................................................................................................................9 2.2. Branch specialization of industrial zones according to town-planning regulations of industrial zones..............9 2.3. The Master plan of Saint-Petersburg (a scheme of a functional zoning of St. Petersburg)..............................................................................................10 2.4. The Rules of land use and building of St. Petersburg (a scheme of a territorial zoning of St. Petersburg).............................................................................................12 2.5. Extent of development of territories of industrial zones and the carried-out projects of engineering training of territories of industrial zones............................................................................................................................13 2.6. Documentation of planning areas of the industrial zones........................................................................13 -

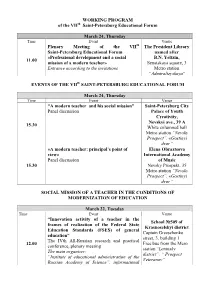

WORKING PROGRAM of the VII Saint-Petersburg Educational

WORKING PROGRAM of the VIIth Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue Plenary Meeting of the VIIth The President Library Saint-Petersburg Educational Forum named after «Professional development and a social B.N. Yeltzin, 11.00 mission of a modern teacher» Senatskaya square, 3 Entrance according to the invitations Metro station “Admiralteyskaya” EVENTS OF THE VIIth SAINT-PETERSBURG EDUCATIONAL FORUM March 24, Thursday Time Event Venue “A modern teacher and his social mission” Saint-Petersburg City Panel discussion Palace of Youth Creativity, Nevskyi ave., 39 A 15.30 White columned hall Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” «A modern teacher: principal’s point of Elena Obraztsova view» International Academy Panel discussion of Music 15.30 Nevsky Prospekt, 35 Metro station “Nevsky Prospect”, «Gostinyi dvor” SOCIAL MISSION OF A TEACHER IN THE CONDITIONS OF MODERNIZATION OF EDUCATION March 22, Tuesday Time Event Venue “Innovation activity of a teacher in the School №509 of frames of realization of the Federal State Krasnoselskyi district Education Standards (FSES) of general Captain Greeschenko education” street, 3, building 1 The IVth All-Russian research and practical 12.00 Free bus from the Mero conference, plenary meeting station “Leninsky The main organizer: district”, “ Prospect “Institute of educational administration of the Veteranov” Russian Academy of Science”, informational and methodological center of Krasnoselskyi district of Saint-Petersburg, School №509 of Krasnoselskyi district March -

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St

List of the Main Directorate of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region № Units Addresses п\п 1 Admiralteysky District of Saint 190013, Saint Petersburg Vereyskaya Street, 39 Petersburg 2 Vasileostrovsky District of Saint 199106, Saint Petersburg, Vasilyevsky Island, 19th Line, 12a Petersburg 3 Vyborgsky District of Saint 194156, Saint Petersburg, Prospekt Parkhomenko, 18 Petersburg 4 Kalininsky District of Saint 195297, Saint Petersburg, Bryantseva Street, 15 Petersburg 5 Kirovsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Avtovskaya Street, 22 Petersburg 6 Kolpinsky District of Saint 198152, Saint Petersburg, Kolpino, Pavlovskaya Street, 1 Petersburg 7 Krasnogvardeisky District of 195027, Saint Petersburg, Bolsheokhtinsky Prospekt, 11/1 Saint Petersburg 8 Krasnoselsky District of Saint 198329, Saint Petersburg, Tambasova Street, 4 Petersburg 9 Kurortny District of Saint 197706, Saint Petersburg, Sestroretsk, Primorskoe Highway, Petersburg 280 10 Kronshtadtsky District of Saint 197760, Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, Lenina Prospekt, 20 Petersburg 11 Moskovsky District of Saint 196135, Saint Petersburg, Tipanova Street, 3 Petersburg 12 Nevsky District of Saint 192171, Saint Petersburg, Sedova Street, 86 Petersburg 13 Petrogradsky District of Saint 197022, Saint Petersburg, Grota Street, 1/3 Petersburg 14 Petrodvortsovy District of Saint 198516, Saint Petersburg, Peterhof, Petersburg Konnogrenaderskaya Street., 1 15 Primorsky District of Saint 197374 Saint Petersburg, Yakhtennaya Street, 7/2 -

The Bolshevik Myth (Diary 1920–22) – Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman The Bolshevik Myth (Diary 1920–22) 1925 Contents Preface . 3 1. The Log of the Transport “Buford” . 5 2. On Soviet Soil . 17 3. In Petrograd . 21 4. Moscow . 29 5. The Guest House . 33 6. Tchicherin and Karakhan . 37 7. The Market . 43 8. In the Moskkommune . 49 9. The Club on the Tverskaya . 53 10. A Visit to Peter Kropotkin . 59 11. Bolshevik Activities . 63 12. Sights and Views . 69 13. Lenin . 75 14. On the Latvian Border . 79 I . 79 II . 83 III . 87 IV . 92 15. Back in Petrograd . 97 16. Rest Homes for Workers . 107 17. The First of May . 111 18. The British Labor Mission . 115 19. The Spirit of Fanaticism . 123 20. Other People . 131 21. En Route to the Ukraina . 137 1 22. First Days in Kharkov . 141 23. In Soviet Institutions . 149 24. Yossif the Emigrant . 155 25. Nestor Makhno . 161 26. Prison and Concentration Camp . 167 27. Further South . 173 28. Fastov the Pogromed . 177 29. Kiev . 187 30. In Various Walks . 193 31. The Tcheka . 205 32. Odessa: Life and Vision . 209 33. Dark People . 221 34. A Bolshevik Trial . 229 35. Returning to Petrograd . 233 36. In the Far North . 241 37. Early Days of 1921 . 245 38. Kronstadt . 249 39. Last Links in the Chain . 261 2 Preface Revolution breaks the social forms grown too narrow for man. It bursts the molds which constrict him the more solidified they become, and the more Life ever striving forward leaves them.In this dynamic process the Russian Revolution has gone further than any previous revolution. -

Vacations in Enter Gauja Manors This Is Your Opportunity to Savour the Jewels That Noblemen Have Safeguarded in the Cusp of the Forest for Time Eternal

EN Vacations in Enter Gauja Manors This is your opportunity to savour the jewels that noblemen have safeguarded in the cusp of the forest for time eternal. Venture forth, rapt in contemplation, essaying your brush back and forth over the canvas, listening to the paint plotting its way into the canvas, and sipping tea in the manor garden, where you will hear the tick tock of the venerable lord’s clock. We invite you to discover Latvia, travelling through time and enjoying the tranquility of the historic residences of the aristocracy fanned by centuries of impressive history. The authentic hospitality of the nobility awaits you, along with the opportunity to step into the world of Latvia’s nobility and to encounter its broad heritage, as well as to embark on a stately journey amid impressive settings nestling among painterly landscapes. During your journey, you will be welcomed at the most important manor houses, castles and palaces in the Gauja region, offering fine dining and accommodation options, and an eclectic offering of additional services, ranging from tours recreating the epochs of the nobility through to scenic horse carriage excursions through the Latvian countryside. TURAIDA MUSEUM RESERVE FROM THE HISTORY Turaida’s historical centre has developed over the course of more than 1,000 years. The events A TREASURE TROVE OF TESTIMONIES TO HISTORY that have taken place here are closely linked to the course of Latvian and European history. Around the 11th century, the Livonian people began living on the shores of the Gauja in Turaida. The rhythm of their daily life was closely attuned to nature. -

Doing Business in St. Petersburg St

Doing business in St. Petersburg St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development – member of Enterprise Europe Network | www.doingbusiness.ru 1 Doing business in St. Petersburg Guide for exporters, investors and start-ups The current publication was developed by and under supervision of Enterprise Europe Network - Russia, Gate2Rubin Consortium, Regional Center - St. Petersburg operated by St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development with the assistance of the relevant legal, human resources, certification, research and real estate firms. © 2014 Enterprise Europe Network - Russia, Gate2Rubin Consortium, Regional Center – St. Petersburg operated by St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development. All rights reserved. International copyright. Any use of materials of this publication is possible only after written agreement of St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development and relevant contributing firms. Doing business in St. Petersburg. – Spb.: Politekhnika-servis, 2014. – 167 p. ISBN 978-5-906555-22-9 Online version available at www.doingbusiness.ru. Doing business in St. Petersburg 2 St. Petersburg Foundation for SME Development – member of Enterprise Europe Network | www.doingbusiness.ru Table of contents 1. The city ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Geography ............................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Public holidays and business hours ...................................................................................... -

St Petersburg Bypass [EBRD

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROJECT FOR CONSTRUCTION OF THE ST. PETERSBURG BY-PASS SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 GENERAL INFORMATION This document covers a brief description of matters related to environmental protection (EP) during the planning, design and construction of the St.Petersburg By- Pass. Ecological Impact Assessment Report sections (EIAR) were prepared during the stage of engineering design, which obtained all the necessary approvals. 1.2 THE NEED FOR THE INVESTMENT To accelerate construction on the basis of the Program of development of the road network "Roads of Russia of XXI century", which was reviewed and approved at the session of the RF Government dated June 28, 2001, the Government of Russian Federation issued directions aimed at speeding up construction of this project. The construction of the By-Pass will divert a considerable part of traffic beyond the borders of the built up areas and thus improve the environmental situation in St.Petersburg by decreasing the traffic volume and increasing the traffic speed. 1.3 BASIC LEGISLATIVE ACTS REGULATING THE USE AND PROTECTION OF CERTAIN KINDS OF RESOURCES S The law of the RSFSR "Protection of environment" of December 19, 1991 (amended by Laws of the Russian Federation of 21 February 1992 No.2397-1, 2 June 1993 No.5076-1, 10 June 2001 No. 93-FZ, 27 December 2000 No. 150-FZ, 30 December 2001 No. 194-FZ, 30 December 2001 No. 196-FZ); 1 S Water Code of the Russian Federation of November 16, 1995. No.167-FZ (amended by Federal Law of 30 December 2001 No. -

Valuation Report PO-36/2017

Valuation Report PO-36/2017 A portfolio of real estate assets in Russia (St Petersburg, Moscow, Yekaterinburg) and Germany (Leipzig, Landshut, Munich) Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Date of issue: March 12, 2018 Contact details LSR Group OJSC, 15-H, liter Ǩ, 36, Kazanskaya St, St Petersburg, 190031, Russia Lyudmila Fradina, Tel. +7 812 3856106, [email protected] Knight Frank Saint-Petersburg AO, Liter A, 3B, Mayakovskogo St., St Petersburg, 191025, Russia Svetlana Shalaeva, Tel. +7 812 3632222, [email protected] Valuation report Ň A portfolio of real estate assets in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow and Moskovskaya Oblast’, Yekaterinburg, Russia and Leipzig, Landshut and Munich, Germany Ň KF Ref: PO-36/2017 Ň Prepared on behalf of LSR Group OJSC Ň Date of issue: March 12, 2018 Page 1 Executive summary The executive summary below is to be used in conjunction with the valuation report to which it forms part and, is subject to the assumptions, caveats and bases of valuation stated herein. It should not be read in isolation. Location The Properties within the Portfolio of real estate assets to be valued are located in St. Petersburg and Leningradskaya Oblast', Moscow, Yekaterinburg, Russia and in Munich, Leipzig and Landshut, Germany. Description The Subject Property is represented by vacant, partly or completely developed land plots intended for residential and commercial development and commercial office buildings with related land plots. Areas Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenure Ɣ Buildings – see the Schedule of Properties below Ɣ Land plots – see the Schedule of Properties below Tenancies As of the valuation date from the data provided by the Client, the office properties are partially occupied by the short-term leaseholders according to the lease agreements. -

Russian Defense Business Directory : St. Petersburg

C 57.121: R 92/996 Prepared by: U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Bureau of Export Administration ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge the contributions of many individuals, agencies and companies to the Directory. The author especially wishes to acknowledge the contributions of Robert May, Dale Slaght, Rich Steffens and Karen Zens of the U.S. & Foreign Commercial Service in Russia and Don Stanton of the Bureau of Export Administration for their contributions. Additional copies of this document*, as well as future installments, may be obtained for a nominal fee from: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Phone: (703) 487-4650, Fax: (703) 321 8547, Telex: 64617 COMNTIS. E-mail: [email protected], Internet: http:Wwww.ntis.gov Order by Publication Number(s): Fifth installment (paper copy): PB96-100177 Copies of the Directory are also available from the: Department of Commerce Economic Bulletin Board (EBB): The Directory highlights and enterprise profiles are available in electronic format through the Department of Commerce's Economic Bulletin Board (EBB). Located under "Defense Conversion Subcommittee Information for Russia and the NIS" (Area 20 on the EBB). For more information regarding access or use, call EBB Info/Help line at (202) 4824986 . National Trade Data Bank: A CD-ROM version of the cumulative version is available in the current edition of the National Trade Data Bank (NTDB) at a cost of $59.00 or annual subscription of $575.00. NTDB's phone number is (202) 482-1986, e-mail: [email protected]. Internet: httpWwww.stat-usa.gov Points of contact for changes and updates to information in the Directory: Franklin J. -

Passport of St. Petersburg

Passport of St. Petersburg Saint Petersburg (St. Petersburg) is situated at the easternmost tip of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea. The exact geographical coordinates of the city centre are 59°57' North Latitude 30°19' East Longitude. St. Petersburg, located in the node of several major sea, river and land transportation routes, is the European gate of Russia and its strategic centre closest to the border with the European Union. Inland waters constitute about 10% of the city territory. The total area (with administrative subjects) covers 1439 km². The population amounts to 5 225.7 people (as of January 1, 2016 by the data from the federal statistical agency “Petrostat”). St. Petersburg is the second (after Moscow) largest city of the Russian Federation and the third (after Moscow and London) largest city in Europe. St. Petersburg is the administrative centre of the Northwestern Federal Region which is characterized by considerable potential in natural resources, well developed industry, a fine traffic network and furthermore provides contact of the Russian Federation with the outside world via the sea ports of the Baltic Sea and the Arctic Ocean. The city hosts the following institutions: • The Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation; • Regional offices of federal ministries and departments; • Representations of 24 entities and 2 cities in the Russian Federation; • 65 consular offices of foreign countries; • Offices of international organizations: CIS Inter-Parliamentary Assembly, Inter-Parliamentary Assembly of the Eurasian Economic Community, representatives of international organizations, funds and associations, UN agencies and representative offices and branches of international banks. • Offices of international cultural institutions: the Goethe German Cultural Center, the French Institute, the Finnish Institute, the Dutch Institute, the Danish Cultural Institute, the Israeli Cultural Center and the Italian Cultural Institute. -

How to Invest in the Industry in Saint Petersburg

The Committee for industrial policy and innovation of St. Petersburg How to invest in the industry in Saint Petersburg 2-d edition | 2015 «HOW TO INVEST IN THE INDUSTRY IN SAINT PETERSBURG» Dear friends! I am glad to welcome the readers of the guide “How to Machines, Admiralteiskie Verfi, Klimov, Concern “Al- invest in the industry in St. Petersburg”. maz – Antey”, “Toyota”, “Hyundai”, “Nissan”, “Novar- St. Petersburg is one of the largest industrial, scien- tis”, “Siemens”, “Bosch”, “Otis”, tific and cultural centers of Russia. Our city is actively Fazer, Heineken and many others. developing such an important sector of the economy Due to the advantageous terms that we offer to as shipbuilding, energy and heavy engineering, auto- investors there are a growing number of residents of motive and pharmaceutical cluster. the Special economic zones, technology parks and To competitive advantages of St. Petersburg is a business incubators, new industrial complexes and unique geographical location, skilled workforce, devel- innovative enterprises in St. Petersburg. oped infrastructure, access to key markets of Russia I invite to St Petersburg of all who aspire to reach new and the European Union, tax and other preferences for heights in business. the investors and operating companies. I am confident that the guide will become your reliable St. Petersburg’s investment climate is considered one source of information and guide in the business world of the best in the country. City Government pays great of the Northern capital. attention to the support and maintenance of invest- ment projects. Welcome to St. Petersburg! St. Petersburg for many years cooperates with the largest Russian and foreign investors. -

Changes in the Population Distribution and Transport Network of Saint Petersburg Xiaoling, Li; Anokhin, Anatolii A.; Shendrik, Alexander V.; Chunliang, Xiu

www.ssoar.info Changes in the population distribution and transport network of Saint Petersburg Xiaoling, Li; Anokhin, Anatolii A.; Shendrik, Alexander V.; Chunliang, Xiu Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Xiaoling, L., Anokhin, A. A., Shendrik, A. V., & Chunliang, X. (2016). Changes in the population distribution and transport network of Saint Petersburg. Baltic Region, 4, 39-60. https://doi.org/10.5922/2079-8555-2016-4-4 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Free Digital Peer Publishing Licence This document is made available under a Free Digital Peer zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den DiPP-Lizenzen Publishing Licence. For more Information see: finden Sie hier: http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ http://www.dipp.nrw.de/lizenzen/dppl/service/dppl/ Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51575-8 L. Xiaoling, A. A. Anokhin, A. V. Shendrik, X. Chunliang The authors explore the interdepend- CHANGES ence between demographic changes and transport network centrality, using Saint IN THE POPULATION Petersburg as an example. The article de- DISTRIBUTION scribes the demographic data for the peri- od 2002—2015 and the transportation net- AND TRANSPORT NETWORK work data of 2006. The authors employ several methods of demographic research; OF SAINT PETERSBURG they identified the centre of gravity of the population, produce the standard devia- tional ellipsis and use the kernel density estimation. The street network centrality of * L. Xiaoling Saint Petersburg was analyzed using the ** A. A. Anokhin Multiple Centrality Assessment Model ** (MCA) and the Urban Network Analysis A.