Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Baikal Russian Federation

LAKE BAIKAL RUSSIAN FEDERATION Lake Baikal is in south central Siberia close to the Mongolian border. It is the largest, oldest by 20 million years, and deepest, at 1,638m, of the world's lakes. It is 3.15 million hectares in size and contains a fifth of the world's unfrozen surface freshwater. Its age and isolation and unusually fertile depths have given it the world's richest and most unusual lacustrine fauna which, like the Galapagos islands’, is of outstanding value to evolutionary science. The exceptional variety of endemic animals and plants make the lake one of the most biologically diverse on earth. Threats to the site: Present threats are the untreated wastes from the river Selenga, potential oil and gas exploration in the Selenga delta, widespread lake-edge pollution and over-hunting of the Baikal seals. However, the threat of an oil pipeline along the lake’s north shore was averted in 2006 by Presidential decree and the pulp and cellulose mill on the southern shore which polluted 200 sq. km of the lake, caused some of the worst air pollution in Russia and genetic mutations in some of the lake’s endemic species, was closed in 2009 as no longer profitable to run. COUNTRY Russian Federation NAME Lake Baikal NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SERIAL SITE 1996: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription. Justification for Inscription The Committee inscribed Lake Baikal the most outstanding example of a freshwater ecosystem on the basis of: Criteria (vii), (viii), (ix) and (x). -

The Fluvial Geochemistry of the Rivers of Eastern Siberia: I. Tributaries Of

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 62, No. 10, pp. 1657–1676, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd Pergamon Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0016-7037/98 $19.00 1 .00 PII S0016-7037(98)00107-0 The fluvial geochemistry of the rivers of Eastern Siberia: I. Tributaries of the Lena River draining the sedimentary platform of the Siberian Craton 1, 1 2 1 YOUNGSOOK HUH, *MAI-YIN TSOI, ALEXANDR ZAITSEV, and JOHN M. EDMONd 1Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA 2Laboratory of Erosion and Fluvial Processes, Department of Geography, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia (Received June 11, 1997; accepted in revised form February 12, 1998) ABSTRACT—The response of continental weathering rates to changing climate and atmospheric PCO2 is of considerable importance both to the interpretation of the geological sedimentary record and to predictions of the effects of future anthropogenic influences. While comprehensive work on the controlling mechanisms of contemporary chemical and mechanical weathering has been carried out in the tropics and, to a lesser extent, in the strongly perturbed northern temperate latitudes, very little is known about the peri-glacial environments in the subarctic and arctic. Thus, the effects of climate, essentially temperature and runoff, on the rates of atmospheric CO2 consumption by weathering are not well quantified at this climatic extreme. To remedy this lack a comprehensive survey has been carried out of the geochemistry of the large rivers of Eastern Siberia, the Lena, Yana, Indigirka, Kolyma, Anadyr, and numerous lesser streams which drain a pristine, high-latitude region that has not experienced the pervasive effects of glaciation and subsequent anthropogenic impacts common to western Eurasia and North America. -

Chronicles of Nature Calendar, a Long-Term and Large-Scale Multitaxon Database on Phenology

www.nature.com/scientificdata OPEN Chronicles of nature calendar, DATA DESCRIPTOR a long-term and large-scale multitaxon database on phenology Otso Ovaskainen et al.# We present an extensive, large-scale, long-term and multitaxon database on phenological and climatic variation, involving 506,186 observation dates acquired in 471 localities in Russian Federation, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan. The data cover the period 1890–2018, with 96% of the data being from 1960 onwards. The database is rich in plants, birds and climatic events, but also includes insects, amphibians, reptiles and fungi. The database includes multiple events per species, such as the onset days of leaf unfolding and leaf fall for plants, and the days for frst spring and last autumn occurrences for birds. The data were acquired using standardized methods by permanent staf of national parks and nature reserves (87% of the data) and members of a phenological observation network (13% of the data). The database is valuable for exploring how species respond in their phenology to climate change. Large-scale analyses of spatial variation in phenological response can help to better predict the consequences of species and community responses to climate change. Background & Summary Phenological dynamics have been recognised as one of the most reliable bio-indicators of species responses to ongoing warming conditions1. Together with other adaptive mechanisms (e.g. changes in the spatial distribution and physiological adaptations), phenological change is a key mechanism by which plants and animals adapt to a changing world2,3. Many studies have documented that in the northern hemisphere, spring events have become earlier whereas autumn events are occurring later than before, mostly due to rising temperatures4–6. -

Preserving the Symbol of Siberia, Moving On: Sobol' and The

EA-13 • RUSSIA • JULY 2009 ICWA Letters INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Preserving the Symbol of Siberia, Moving On: Sobol’ and the Elena Agarkova is studying management Barguzinsky Zapovednik (Part I) of natural resources and the relationship between By Elena Agarkova Siberia’s natural riches and its people. Previously, Elena was a Legal Fellow at the LAKE BAIKAL–I started researching this news- University of Washington’s letter with a plan to write about the Barguzin- School of Law, at the sky zapovednik, a strict nature reserve on the Berman Environmental eastern shore of Baikal, the first and the old- Law Clinic. She has clerked est in the country.1 I went to Nizhneangarsk, a for Honorable Cynthia M. Rufe of the federal district small township at the north shore of the lake, court in Philadelphia, and where the zapovednik’s head office is located has practiced commercial now. I crossed the lake and hiked on the east- litigation at the New York ern side through some of the zapovednik’s ter- office of Milbank, Tweed, ritory. I talked to people who devoted their lives Hadley & McCloy LLP. Elena to preserving a truly untouched wilderness, on was born in Moscow, Rus- a shoestring budget. And along the way I found sia, and has volunteered for myself going in a slightly different direction environmental non-profits than originally planned. An additional protago- in the Lake Baikal region of Siberia. She graduated nist emerged. I became fascinated by a small, from Georgetown Universi- elusive animal that played a central role not ty Law Center in 2001, and only in the creation of Russia’s first strict nature has received a bachelor’s reserve, but in the history of Russia itself. -

The Potential for Integration of the Transport Complex of the East of Russia Into the International Market of Transport Services

BRANCH-WISE ECONOMY DOI: 10.15838/esc.2019.6.66.8 UDC 332.1+339.924, LBC 65.049(2) © Bardal’ A.B. The Potential for Integration of the Transport Complex of the East of Russia into the International Market of Transport Services Anna B. Bardal’ Economic Research Institute, Far Eastern Branch of RAS Khabarovsk, Russian Federation, 153,Tikhookeanskaya Street, 680042 E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-9944-4714; ResearcherID: V-7615-2017 Abstract. The eastern regions of Russia are the convenient zone in which Russia cooperates with the actively developing Asian region. The key states of North-East Asia such as China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea are the largest participants in world trade at the present stage. The servicing of large- scale commodity flows with the European Union and the U.S. is provided by the market of transport services, by means of which the most effective schemes of delivery are built. Under these conditions, the transport system of the East of Russia has objective prerequisites for integration into the international transport system. The goal of our present study is to assess the potential of integration of the transport system of the Far East in the market of transport services in North-East Asia. At the same time, we assess integration opportunities with the help of dividing the territory of the East of Russia into districts based on the results of cluster analysis. Considering the achievement of the research goal, this approach is a new one. The need for division is due to the fact that the Far East is quite a large region, extremely heterogeneous in its internal composition, economic-geographical and socio-economic characteristics. -

Амурский Зоологический Журнал Amurian Zoological Journal

Амурский зоологический журнал Amurian zoological journal Том VIII. № 1 Март 2016 Vol. VIII. No 1 March 2016 Амурский зоологический журнал ISSN 1999-4079 Рег. свидетельство ПИ № ФС77-31529 Amurian zoological journal Том VIII. № 1. Vol. VIII. № 1. Март 2016 www.bgpu.ru/azj/ March 2016 РЕДАКЦИОННАЯ КОЛЛЕГИЯ EDITORIAL BOARD Главный редактор Editor-in-chief Член-корреспондент РАН, д.б.н. Б.А. Воронов Corresponding Member of R A S, Dr. Sc. Boris A. Voronov к.б.н. А.А. Барбарич (отв. секретарь) Dr. Alexandr A. Barbarich (exec. secretary) к.б.н. Ю. Н. Глущенко Dr. Yuri N. Glushchenko д.б.н. В. В. Дубатолов Dr. Sc. Vladimir V. Dubatolov д.н. Ю. Кодзима Dr. Sc. Junichi Kojima к.б.н. О. Э. Костерин Dr. Oleg E. Kosterin д.б.н. А. А. Легалов Dr. Sc. Andrei A. Legalov д.б.н. А. С. Лелей Dr. Sc. Arkadiy S. Lelej к.б.н. Е. И. Маликова Dr. Elena I. Malikova д.б.н. В. А. Нестеренко Dr. Sc. Vladimir A. Nesterenko д.б.н. М. Г. Пономаренко Dr. Sc. Margarita G. Ponomarenko к.б.н. Л.А. Прозорова Dr. Larisa A. Prozorova д.б.н. Н. А. Рябинин Dr. Sc. Nikolai A. Rjabinin д.б.н. М. Г. Сергеев Dr. Sc. Michael G. Sergeev д.б.н. С. Ю. Синев Dr. Sc. Sergei Yu. Sinev д.б.н. В.В. Тахтеев Dr. Sc. Vadim V. Takhteev д.б.н. И.В. Фефелов Dr. Sc. Igor V. Fefelov д.б.н. А.В. Чернышев Dr. Sc. Alexei V. Chernyshev к.б.н. -

New Bryophyte Records. 4 – Новые Бриологические Находки

Arctoa (2015) 24: 224-264 doi: 10.15298/arctoa.24.23 NEW BRYOPHYTE RECORDS. 4 – НОВЫЕ БРИОЛОГИЧЕСКИЕ НАХОДКИ. 4 Sofronova E.V. (ed.), O.M. Afonina, T.V. Akatova, Софронова Е.В. (ред.), О.М. Афонина, Т.В. Ака- E.N. Andrejeva, E.Z. Baisheva, A.G. Bezgodov, I.V. това, Е.Н. Андреева, Э.З. Баишева, А.Г. Безгодов, И.В. Blagovetshenskiy, E.A. Borovichev, E.V. Chemeris, A.M. Благовещенский, Е.А. Боровичев, Е.В. Чемерис, А.М. Chernova, I.V.Czernyadjeva, G.Ya. Doroshina, N.V. Du- Чернова, И.В. Чернядьева, Г.Я. Дорошина, Н.В. Дуда- dareva, S.V. Dudov, M.V. Dulin, V.E. Fedosov, S.M. рева, С.В. Дудов, М.В. Дулин, В.Э. Федосов, С.М. Gabitova, M.S. Ignatov, E.A. Ignatova, O.A. Kapitono- Габитова, М.С. Игнатов, Е.А. Игнатова, О.А. Капи- va, S.G. Kazanovsky, V.M. Kotkova, O.V. Lavrinenko, тонова, С.Г. Казановский, В.М. Коткова, О.В. Лаври- Yu.S. Mamontov, A. Mežaka, O.A. Mochalova, I.A. Ni- ненко, Ю.С. Мамонтов, А. Межака, О.А. Мочалова, kolajev, E.Yu. Noskova, A.A. Notov, D.A. Philippov, И.А. Николаев, Э.Ю. Носкова, A.A. Нотов, Д.А. Филип- O.Yu. Pisarenko, N.N. Popova, A.D. Potemkin, E.I. Ro- пов, О.Ю. Писаренко, Н.Н. Попова, А.Д. Потёмкин, Е.И. zantseva, V.V. Teleganova, Ts. Tsegmed, V.I. Zolotov Розанцева, В.В. Телеганова, Ц. Цэгмэд, В.И. Золотов New liverwort records from Murmansk Province. евой (Afonina & Czernyadjeva, 1995) этот вид указы- 5. -

The Petroleum Potential of the Riphean–Vendian Succession of Southern East Siberia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/253369249 The petroleum potential of the Riphean–Vendian succession of southern East Siberia CHAPTER in GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LONDON SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS · MAY 2012 Impact Factor: 2.58 · DOI: 10.1144/SP366.1 CITATIONS READS 2 95 4 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Olga K. Bogolepova Uppsala University 51 PUBLICATIONS 271 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Alexander P. Gubanov Scandiz Research 55 PUBLICATIONS 485 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Olga K. Bogolepova Retrieved on: 08 March 2016 Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on March 25, 2013 Geological Society, London, Special Publications The petroleum potential of the Riphean-Vendian succession of southern East Siberia James P. Howard, Olga K. Bogolepova, Alexander P. Gubanov and Marcela G?mez-Pérez Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2012, v.366; p177-198. doi: 10.1144/SP366.1 Email alerting click here to receive free e-mail alerts when service new articles cite this article Permission click here to seek permission to re-use all or request part of this article Subscribe click here to subscribe to Geological Society, London, Special Publications or the Lyell Collection Notes © The Geological Society of London 2013 Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on March 25, 2013 The petroleum potential of the Riphean–Vendian succession of southern East Siberia JAMES P. HOWARD*, OLGA K. BOGOLEPOVA, ALEXANDER P. GUBANOV & MARCELA GO´ MEZ-PE´ REZ CASP, West Building, 181a Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DH, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The Siberian Platform covers an area of c. -

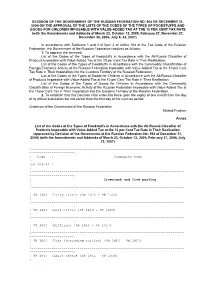

Decision of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 908 of December 31, 2004 on the Approval of the Lists of the Codes of T

DECISION OF THE GOVERNMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION NO. 908 OF DECEMBER 31, 2004 ON THE APPROVAL OF THE LISTS OF THE CODES OF THE TYPES OF FOODSTUFFS AND GOODS FOR CHILDREN IMPOSABLE WITH VALUE-ADDED TAX AT THE 10 PER CENT TAX RATE (with the Amendments and Addenda of March 23, October 12, 2005, February 27, November 27, December 30, 2006, July 9, 23, 2007) In accordance with Subitems 1 and 2 of Item 2 of Article 164 of the Tax Code of the Russian Federation, the Government of the Russian Federation resolves as follows: 1. To approve the annexed: List of the Codes of the Types of Foodstuffs in Accordance with the All-Russia Classifier of Products Imposable with Value-Added Tax at the 10 per Cent Tax Rate in Their Realisation; List of the Codes of the Types of Foodstuffs in Accordance with the Commodity Classification of Foreign Economic Activity of the Russian Federation Imposable with Value-Added Tax at the 10 per Cent Tax Rate in Their Importation into the Customs Territory of the Russian Federation; List of the Codes of the Types of Goods for Children in Accordance with the All-Russia Classifier of Products Imposable with Value-Added Tax at the 10 per Cent Tax Rate in Their Realisation; List of the Codes of the Types of Goods for Children in Accordance with the Commodity Classification of Foreign Economic Activity of the Russian Federation Imposable with Value-Added Tax at the 10 per Cent Tax in Their Importation into the Customs Territory of the Russian Federation. -

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1

RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 1 No. 33 Summer 2003 Special issue: The Transformation of Protected Areas in Russia A Ten-Year Review PROMOTING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN RUSSIA AND THROUGHOUT NORTHERN EURASIA RCN #33 21/8/03 13:57 Page 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS Voice from the Wild (Letter from the Editors)......................................1 Ten Years of Teaching and Learning in Bolshaya Kokshaga Zapovednik ...............................................................24 BY WAY OF AN INTRODUCTION The Formation of Regional Associations A Brief History of Modern Russian Nature Reserves..........................2 of Protected Areas........................................................................................................27 A Glossary of Russian Protected Areas...........................................................3 The Growth of Regional Nature Protection: A Case Study from the Orlovskaya Oblast ..............................................29 THE PAST TEN YEARS: Making Friends beyond Boundaries.............................................................30 TRENDS AND CASE STUDIES A Spotlight on Kerzhensky Zapovednik...................................................32 Geographic Development ........................................................................................5 Ecotourism in Protected Areas: Problems and Possibilities......34 Legal Developments in Nature Protection.................................................7 A LOOK TO THE FUTURE Financing Zapovedniks ...........................................................................................10 -

NATIONAL PROTECTED AREAS of the RUSSIAN FEDERATION: of the RUSSIAN FEDERATION: AREAS PROTECTED NATIONAL Vladimir Krever, Mikhail Stishov, Irina Onufrenya

WWF WWF is one of the world’s largest and most experienced independent conservation WWF-Russia organizations, with almost 5 million supporters and a global network active in more than 19, bld.3 Nikoloyamskaya St., 100 countries. 109240 Moscow WWF’s mission is to stop the degradation of the planet’s natural environment and to build a Russia future in which humans live in harmony with nature, by: Tel.: +7 495 727 09 39 • conserving the world’s biological diversity Fax: +7 495 727 09 38 • ensuring that the use of renewable natural resources is sustainable [email protected] • promoting the reduction of pollution and wasteful consumption. http://www.wwf.ru The Nature Conservancy The Nature Conservancy - the leading conservation organization working around the world to The Nature Conservancy protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and people. Worldwide Office The mission of The Nature Conservancy is to preserve the plants, animals and natural 4245 North Fairfax Drive, Suite 100 NNATIONALATIONAL PPROTECTEDROTECTED AAREASREAS communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters Arlington, VA 22203-1606 they need to survive. Tel: +1 (703) 841-5300 http://www.nature.org OOFF TTHEHE RRUSSIANUSSIAN FFEDERATION:EDERATION: MAVA The mission of the Foundation is to contribute to maintaining terrestrial and aquatic Fondation pour la ecosystems, both qualitatively and quantitatively, with a view to preserving their biodiversity. Protection de la Nature GGAPAP AANALYSISNALYSIS To this end, it promotes scientific research, training and integrated management practices Le Petit Essert whose effectiveness has been proved, while securing a future for local populations in cultural, 1147 Montricher, Suisse economic and ecological terms. -

Chapter 5. Project Environmental Impact 63 5.1

E1188 TRANSLATION FROM RUSSIAN Preparation stage for the Project on Fire Management in High Conservation Value Forests of the Amur-Sikhote-Alin Ecoregion Grant GEF PPG TF051241 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized F I N A L R E P O R T Project on Fire Management in High Conservation Value Forests of the Amur- Sikhote-Alin Ecoregion Environmental Impact Assessment Public Disclosure Authorized EIA Leader D.Biol. B.A. Voronov Public Disclosure Authorized Khabarovsk – February 2005 2 Summary Report: 125 pages, figures 4, tables 12, references 70, supplements 2 AMUR-SIKHOTE-ALIN ECOREGION, HIGH CONSERVATION VALUE FORESTS, MODEL TERRITORIES, RESERVES, FOREST FIRE MANAGEMNT, CONSERVATION, BIODIVERSITY Analysis and assessment of Project on Fire Management in High Conservation Value Forests of the Amur-Sikhote-Alin Ecoregion Goals: assessment of Project environmental impact and contribution to the implementation of the program on forest fire prevention, elimination and control in the Amur-Sikhote-Alin ecoregion. Present-day situation, trends and opportunities for developing a fire prevention, elimination and control system were in the focus of attention. Existing data and materials have been studied to reveal forest fire impact on environment as well as Project environmental impact. Project under consideration is aimed at improving current fire management system and strengthening protection of ecoregion forests from degradation, which make it extremely socially and ecologically valuable and important. 3 List of Specialists Senior researcher, C.Biol.Sc. A.L. Antonov (Chapter 3) Senior researcher, D.Biol. B.A. Voronov (Introduction, Chapters 2,5,6) Senior researcher, C.Agr.Sc. A.K. Danilin (Chapter 4) Senior researcher, C.Biol.Sc.