Improving the Aesthetic and Other Experiential Design Aspects of Bicycle Paths in Western Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines

AUSTRALIAN ADAPTIVE MOUNTAIN BIKING GUIDELINES A detailed guide to help land managers, trail builders, event directors, mountain bike clubs, charities and associations develop inclusive mountain bike trails, events and programs for people with disabilities in Australia. Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines AUSTRALIAN ADAPTIVE MOUNTAIN BIKING GUIDELINES Version 1.0.0 Proudly supported and published by: Mountain Bike Australia Queensland Government Acknowledgements: The authors of this document acknowledge the contribution of volunteers in the preparation and development of the document’s content. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to the following contributors: Denise Cox (Mountain Bike Australia), Talya Wainstein, Clinton Beddall, Richard King, Cameron McGavin and Ivan Svenson (Kalamunda Mountain Bike Collective). Photography by Kerry Halford, Travis Deane, Emily Dimozantos, Matt Devlin and Leanne Rees. Editing and Graphics by Ripe Designs Graphics by Richard Morrell COPYRIGHT 2018: © BREAK THE BOUNDARY INC. This document is copyright protected apart from any use as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Author. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to the Author at www.breaktheboundary.com Fair-use policy By using this document, the user agrees to this fair-use policy. This document is a paid publication and as such only for use by the said paying person, members and associates of mountain bike and adaptive sporting communities, clubs, groups or associations. Distribution or duplication is strictly prohibited without the written consent of the Author. The license includes online access to the latest revision of this document and resources at no additional cost and can be obtained from: www.breaktheboundary.com Hard copies can be obtained from: www.mtba.asn.au 3 Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines CONTENTS 1. -

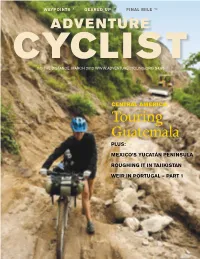

Adventure Cyclist and Dis- Counts on Adventure Cycling Maps

WNTAYPOI S 8 GEARED UP 40 FINAL MILE 52 A DVENTURE C YCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. MARCH 2012 WWW.ADVentURECYCLING.ORG $4.95 CENTRAL AMERICA: Touring Guatemala PLUS: MEXIco’S YUCATÁN PENINSULA ROUGHING IT IN TAJIKISTAN WEIR IN PORTUGAL – PART 1 3:2012 contents March 2012 · Volume 39 Number 2 · www.adventurecycling.org A DVENTURE C YCLIST is published nine times each year by the Adventure Cycling Association, a nonprofit service organization for recreational bicyclists. Individual membership costs $40 yearly to U.S. addresses and includes a subscrip- tion to Adventure Cyclist and dis- counts on Adventure Cycling maps. The entire contents of Adventure Cyclist are copyrighted by Adventure Cyclist and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from Adventure Cyclist. All rights reserved. OUR COVER Cara Coolbaugh encounters a missing piece of road in Guatemala. Photo by T Cass Gilbert. R E LB (left) Local Guatemalans are sur- GI prised to see a female traveling by CASS bike in their country. MISSION CYCLE THE MAYAN KINGDOM ... BEFORE IT’s TOO LATE by Cara Coolbaugh The mission of Adventure Cycling 10 Guatemela will test the mettle of both you and your gear. But it’s well worth the effort. Association is to inspire people of all ages to travel by bicycle. We help cyclists explore the landscapes and THE WONDROUS YUCATÁN by Charles Lynch history of America for fitness, fun, 20 Contrary to the fear others perceived, an American finds a hidden gem for bike touring. and self-discovery. CAMPAIGNS TAJIKISTAN IS FOR CYCLISTS by Rose Moore Our strategic plan includes three 26 If it’s rugged, spectacular bike travel that you seek, look no further than Central Asia. -

Tandems Owner’S Manual Supplement 116831.PDF Revision 2

READ THIS MANUAL CAREFULLY! It contains important safety information. Keep it for future reference. Tandems Owner’s Manual Supplement 116831.PDF Revision 2 CONTENTS GENERAL SAFETY INFORMATION ......... 2 TECHNICAL SECTION ............................12 About This Supplement ............................... 2 Stoker Handlebar System ...........................12 Special Manual Messages ........................... 2 About Tandem Forks ....................................13 Intended Use ................................................. 3 Brake Systems ...............................................13 Building Up A Frameset ............................... 3 Rim, Hydraulic and Rear Drum Brakes .....14 TANDEM RIDING ................................... 4 Timing Chain Tension ..................................12 The Captain’s Responsibility ....................... 4 Derailleur BB Cable Routing ......................15 The Stoker ........................................................ 5 Adjusting the Timing Chain .......................18 Tandem Bike Fit .............................................. 5 MAINTENANCE .................................... 22 Getting Underway ........................................6 GEOMETRY ........................................... 23 Starting Off .....................................................6 Stopping ..........................................................8 REPLACEMENT PARTS (KITS) .................25 Slow Speed Riding .........................................8 OWNER NOTES ................................... -

Download the Toronto Cycling Handbook: Family Edition

The Toronto Cycling Handbook: Family Edition Everything you need to know about family cycling in the city, all in one book First edition, 2019 1 /// Contents IN PARTNERSHIP WITH CultureLink is a settlement and Reasons to ride as a family 3 community organization with 30 The bicycle 4 years’ experience in developing and delivering services to meet the needs of diverse Biking while pregnant 6 communities. They are dedicated to facilitating the Biking with babies & toddlers (age 0-4) 7 active participation and integration of newcomers and the broader community, recognizing the Biking with kids on board (age 3-7) 8 interdependence of these groups in our society. Learn more at www.culturelink.ca Learning to bike to school (age 6-10) 10 Biking to school (age 9-13) 12 Cycle Toronto is a member-supported FAQs and Nice-to-haves 14 not-for-profit organization that works to make Toronto a healthy, safe, and vibrant cycling city for all. They Join over 1.4 million Torontonians focus on advocacy, education and encouragement who ride bicycles because it’s to shape policy and infrastructure, and build convenient, healthy, affordable community to transform Toronto’s cycling culture. They engage a diversity of people in their work, and fun. pursuing evidence-based solutions that make This handbook will teach you about family cycling a viable option for all Torontonians. Become cycling, from pregnancy through grade 8. a member: www.cycleto.ca/join When riding your bikes in Toronto, always remember to use your best judgement, take The Toronto Cycling Think & your time and have fun! For the original Do Tank is a multidisciplinary, handbook, go to www.cycleto.ca/handbook multi-sector research project focused on increasing cycling as The Toronto Cycling Handbook: a primary transportation choice. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Shooting Star: a Biography of a Bicycle

SHOOTING STAR: A BIOGRAPHY OF A BICYCLE Geoff Mentzer 2 SHOOTING STAR: A BIOGRAPHY OF A BICYCLE Copyright © 2020 by Geoff Mentzer All rights reserved. 3 In a scientific study of various living species and machines, the most efficient at locomotion – that is, the least amount of energy expended to move a kilometre – was found to be a man on a bicycle. –SS Wilson, Scientific American, March 1973, Volume 228, Issue 3, 90 The Dandy Horse of 1818, said to be the first velocipede man-motor carriage. Sharp, Bicycles & Tricycles: An Elementary Treatise On Their Design And Construction, Longmans, Green, and Co, London, New York and Bombay, 1896, 147 4 INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What began as a brief biograph of the author's forebear Walter William Curties soon doubled into a study of two men, and expanded into an account of early bicycle – and a little motoring – history in New Zealand. Curties is mostly invisible to history, while Frederick Nelson Adams – who rose to national pre-eminence in motoring circles – by his reticence and reluctance for public exposure is also largely overlooked. Pioneering New Zealand cycling and motoring history – commercial, industrial and social – have been variously covered elsewhere, in cursory to comprehensive chronicles. Sadly, factual errors that persist are proof of copy and paste research. As examples, neither Nicky Oates nor Frederick Adams' brother Harry was the first person convicted in New Zealand for a motoring offence, nor was the world's first bicycle brass band formed in New Zealand. It must be said, however, that today we have one great advantage, ie Papers Past, that progeny of the Turnbull Library in Wellington. -

Bicycles, Tandems and More

2008 BICYCLES, TANDEMS AND MORE SINCE 1973 5627 University Way NE Seattle, WA 98105 206-527-4822 Fax 206-527-8931 35 Years and still rollin’ strong! www.rodcycle.com 1. Who are we? “Buy a shop? Me?”, you ask. Yes, you. That’s the As you look through our 2008 catalog, you’ll notice that best advice that you can get when you are shopping we manufacture more than just bikes. You’ll notice that for a bicycle. What it means is the difference be- we write software, manufacture highly specialized bicycle tween shops is greater than the difference between parts, and made our own phenomenal adjustable fi tting bike brands. machine. All of these products were designed, engi- neered, and produced right here in our shop by people Our philosophy is that when you choose your bi- who have dedicated their lives to the bicycle business. cycle, you should choose it based on the folks who will not only build your bicycle, but also those who A lot of people are surprised when they learn that we will help you get comfortable on the bike, as well as are just 15 people, fi tting, selling, manufacturing, and provide service down the road as you need it. servicing bicycles all in one shop in Seattle’s University District. The truth is, the talented people that work Have you heard of us? here do it because of their love for bicycles and our If you’ve heard of us, it’s not because you saw us in customers who ride them. -

4-H Bicycling Project – Reference Book

4-H MOTTO Learn to do by doing. 4-H PLEDGE I pledge My HEAD to clearer thinking, My HEART to greater loyalty, My HANDS to larger service, My HEALTH to better living, For my club, my community and my country. 4-H GRACE (Tune of Auld Lang Syne) We thank thee, Lord, for blessings great On this, our own fair land. Teach us to serve thee joyfully, With head, heart, health and hand. This project was developed through funds provided by the Canadian Agricultural Adaptation Program (CAAP). No portion of this manual may be reproduced without written permission from the Saskatchewan 4-H Council, phone 306-933-7727, email: [email protected]. Developed in January 2013. Writer: Leanne Schinkel Table of Contents Introduction Objectives .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Getting the Most from this Project ....................................................................................................... 1 Achievement Requirements for this Project ..................................................................................... 2 Safety and Bicycling ................................................................................................................................. 2 Online Safety .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Resources for Learning ............................................................................................................................ -

This Instruction Booklet Contains Important Safety Information. Please Read and Keep for Future Reference

THIS INSTRUCTION BOOKLET CONTAINS IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION. PLEASE READ AND KEEP FOR FUTURE REFERENCE. FOR SERVICE ASSISTANCE CALL KENT TOLL FREE 1.800.451.5368 Monday - Friday 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time Congratulations on the purchase of your new bike! With proper assembly and maintenance it will offer you years of enjoyable riding! IMPORTANT: Carefully read and follow this manual (and any other materials included with this bike) before riding. Please retain this manual for future use. If this bike was purchased for a child, it is the responsibility of the purchaser to verify the bike has been properly assembled, and that the user has been properly trained and instructed in use of the bike. This manual is provided to assist you and is not intended to be a comprehensive manual covering all aspects of maintaining and repairing your bicycle. The bicycle you have purchased is a complex piece of equipment that must be properly assembled and maintained in order to be ridden safely. If you have any doubts about the assembly or your ability to properly assemble and maintain the bicycle. You must have it assembled and maintained by a professional bicycle mechanic. DANGER! Failure to properly assemble and maintain your bicycle could result in serious injury or death to the rider. ALWAYS WEAR A PROPERLY FITTED Check and read this decal on HELMET WHEN YOU RIDE YOUR your bicycle before each ride: BICYCLE. DO NOT RIDE AT NIGHT. AVOID RIDING IN WET CONDITIONS. RESPONSIBILITY OF THE OWNER! IMPORTANT: Reading and following the information and instructions in this manual are essential to your ability to ride safely. -

Inclusion/Adaptive Recreation Office 1301 Valley Road Reno, NV 89512 (775) 333-7765 Reno.Gov/Adaptive

EQUIPMENT RENTAL PROGRAM Our adaptive recreation equipment is available for rent. Renting makes it affordable for participants to try before they buy, be a weekend warrior, gain skills, and be involved in more than one sport. Please note -- A minimum of 48 hours advance notice is preferred. Equipment inventory is limited and an appointment for proper fit is required. Inclusion/Adaptive Recreation Office 1301 Valley Road Reno, NV 89512 (775) 333-7765 Reno.Gov/Adaptive FEES & AGREEMENTS • The rental fee must be paid in advance. The daily fee is $15, weekend fee is $50 and full-week fee is $75. INCLUSION • A valid credit card is required. Its image will be CITY OF RENO held to make repairs on damaged, lost or stolen equipment, if necessary. The renter is responsible for replacement and repair costs. • The renter agrees to be the sole authorized user of ADAPTIVE the equipment. • A Release Agreement will be read and signed prior to leaving the premises. The Release Agreement EQUIPMENT requires the signature of either a parent or legal guardian if the renter is under the age of 18 or not their own guardian. RENTAL • The renter must be at least one-year post injury and must be their own legal guardian if over the age of 18. Equipment provided by a grant from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation 1 7 1 CATRIKE RECUMBENT TRIKES 8 TOP END FORCE HANDCYCLE Sizes Available: Adult | Models: Villager, Road, 700 Sizes Available: Adult | Models: Force R, Gold, Force 3 The Catrike is a premium grade Recumbent trike suited for all Quad Elite, Quad Exelerator day touring and spirited rides. -

The Physiological Effects of Cycling on Tandem and Single Bicycles J G Seifert, D W Bacharach, E R Burke

50 Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.50 on 1 February 2003. Downloaded from ORIGINAL ARTICLE The physiological effects of cycling on tandem and single bicycles J G Seifert, D W Bacharach, E R Burke ............................................................................................................................. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:50–53 Objective: The purpose of this field study was to compare the physiological responses from cycling on a tandem road bicycle to those from cycling on a single road bicycle. Methods: Nine pairs of experienced, recreational tandem cyclists rode a tandem or their single bicy- cle for 5 min at each velocity of 19.3, 22.5, 25.8, and 29.0 kph on a flat, paved surface. Heart rate See end of article for (HR), rating of perceived exertion (RPE), and lactic acid (LA) data were collected after each interval. authors’ affiliations Results: Riding a tandem resulted in lower HR, RPE, and LA mean values across the four velocities ....................... compared to the single bicycle. Mean (SD) HR, RPE, and LA for tandem and single bicycles were 126 Correspondence to: (20.7) v 142 (20.1) bpm, 10.1 (1.7) v 11.3 (2.6), and 1.46 (1.0) mM/L v 2.36 (1.7) mM/L, respec- J G Seifert, Department of tively. No position differences were observed between the captain and stoker (front and rear positions) Physical Education & Sport when both were on the tandem. Stokers had significantly lower HR, LA, and RPE values when they rode Science, Human a tandem compared to a single bicycle. No statistical differences were observed between bicycles for Performance Laboratory, St. -

The Journal Journal

The Journal of the International Veteran Cycle Association Issue No. 52 March 2014 For more information see pages 23, 24 in this Journal or email [email protected] Contents President’s message…………..page 3 Le mot du President…………..page 3 Bericht des Prasedente…….....Seite 4 Items of Interest………………......5-7 Points d'intérêt …………………..5-7 Interessante Artikel ……….…….5-7 New books……………………....8-10 Nouveaux livres ………………...8-10 Neue Bücher …………..……….8-10 Reports of events…………..…..11-17 Rapport………………...………11-17 Berichte ……………...………..11-17 Calendar of events………….….18-23 Calendrier des événements ..…..18-23 Veranstaltungskalender ……….18-23 Next Rally 2014 in Hungary..…24-25 Rallye 2014 en Hongrie …….…24-25 Nächste Rallye in Ungarn …….24-25 Advertisements………………..25-26 Annonces ……………………...25-26 Werbung ………………...…….25-26 The International Veteran Cycle ASSOCIATION The International Veteran Cycle Association (IVCA) is an association of organizations and individuals interested in vintage bicycles: riding, collecting, restoration, history and their role in society. Statement of Purpose The International Veteran Cycle Association is dedicated to the preservation of the history of the bicycle and bicycling and the enjoyment of the bicycle as a machine. On 26th May 1986, at Lincoln ,UK, the International Veteran Cycle Association (IVCA in short) was formed by Veteran Cycle Clubs, Museums and Collectors of old pedal cycles and related objects from various countries. The Objectives of the Association are: To encourage interests and activities relating to all old human-powered vehicles of one or more wheels deriving from the velocipede tradition. To support and encourage research and classification of their history and to act as a communication medium between clubs, societies and museums world-wide on mutual matters relating to old cycles.