Shooting Star: a Biography of a Bicycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines

AUSTRALIAN ADAPTIVE MOUNTAIN BIKING GUIDELINES A detailed guide to help land managers, trail builders, event directors, mountain bike clubs, charities and associations develop inclusive mountain bike trails, events and programs for people with disabilities in Australia. Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines AUSTRALIAN ADAPTIVE MOUNTAIN BIKING GUIDELINES Version 1.0.0 Proudly supported and published by: Mountain Bike Australia Queensland Government Acknowledgements: The authors of this document acknowledge the contribution of volunteers in the preparation and development of the document’s content. The authors would also like to extend their gratitude to the following contributors: Denise Cox (Mountain Bike Australia), Talya Wainstein, Clinton Beddall, Richard King, Cameron McGavin and Ivan Svenson (Kalamunda Mountain Bike Collective). Photography by Kerry Halford, Travis Deane, Emily Dimozantos, Matt Devlin and Leanne Rees. Editing and Graphics by Ripe Designs Graphics by Richard Morrell COPYRIGHT 2018: © BREAK THE BOUNDARY INC. This document is copyright protected apart from any use as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Author. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to the Author at www.breaktheboundary.com Fair-use policy By using this document, the user agrees to this fair-use policy. This document is a paid publication and as such only for use by the said paying person, members and associates of mountain bike and adaptive sporting communities, clubs, groups or associations. Distribution or duplication is strictly prohibited without the written consent of the Author. The license includes online access to the latest revision of this document and resources at no additional cost and can be obtained from: www.breaktheboundary.com Hard copies can be obtained from: www.mtba.asn.au 3 Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines Australian Adaptive Mountain Biking Guidelines CONTENTS 1. -

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516 Phone: 518-329-1142 December 1, 2012 Pedaling History Bicycle Museum Auction 12/1/2012 LOT # LOT # 1 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed 6 Royal Doulton Pitcher and Tumbler 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed. Site, 81" x 41". English Doulton Lambeth Pitcher 161, and "Niagara Lith. Co. Buffalo, NY 1898". Superb Royal-Doulton tumbler 1957. Estimate: 75.00 - condition, probably the best known example. 125.00 Estimate: 3,000.00 - 5,000.00 7 League Shaft Drive Chainless Bicycle 2 46" Springfield Roadster High Wheel Safety Bicycle C. 1895 League, first commercial chainless, C. 1889 46" Springfield Roadster high wheel rideable, very rare, replaced headbadge, grips safety. Rare, serial #2054, restored, rideable. and spokes. Estimate: 3,200.00 - 3,700.00 Estimate: 4,500.00 - 5,000.00 8 Wood Brothers Boneshaker Bicycle 3 50" Victor High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. 1869 Wood Brothers boneshaker, 596 C. 1888 50" Victor "Junior" high wheel, serial Broadway, NYC, acorn pedals, good rideable, #119, restored, rideable. Estimate: 1,600.00 - 37" x 31" diameter wheels. Estimate: 3,000.00 - 1,800.00 4,000.00 4 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle 9 Elliott Hickory Hard Tire Safety Bicycle C. 1886 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel C. 1891 Elliott Hickory model B. Restored and "Challenge", older restoration, incorrect step. rideable, 32" x 26" diameter wheels. Estimate: Estimate: 1,700.00 - 1,900.00 2,800.00 - 3,300.00 4a Gormully & Jeffery High Wheel Safety Bicycle 10 Columbia High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. -

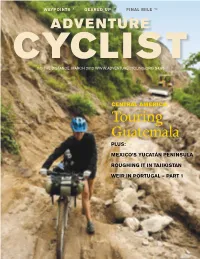

Adventure Cyclist and Dis- Counts on Adventure Cycling Maps

WNTAYPOI S 8 GEARED UP 40 FINAL MILE 52 A DVENTURE C YCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. MARCH 2012 WWW.ADVentURECYCLING.ORG $4.95 CENTRAL AMERICA: Touring Guatemala PLUS: MEXIco’S YUCATÁN PENINSULA ROUGHING IT IN TAJIKISTAN WEIR IN PORTUGAL – PART 1 3:2012 contents March 2012 · Volume 39 Number 2 · www.adventurecycling.org A DVENTURE C YCLIST is published nine times each year by the Adventure Cycling Association, a nonprofit service organization for recreational bicyclists. Individual membership costs $40 yearly to U.S. addresses and includes a subscrip- tion to Adventure Cyclist and dis- counts on Adventure Cycling maps. The entire contents of Adventure Cyclist are copyrighted by Adventure Cyclist and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from Adventure Cyclist. All rights reserved. OUR COVER Cara Coolbaugh encounters a missing piece of road in Guatemala. Photo by T Cass Gilbert. R E LB (left) Local Guatemalans are sur- GI prised to see a female traveling by CASS bike in their country. MISSION CYCLE THE MAYAN KINGDOM ... BEFORE IT’s TOO LATE by Cara Coolbaugh The mission of Adventure Cycling 10 Guatemela will test the mettle of both you and your gear. But it’s well worth the effort. Association is to inspire people of all ages to travel by bicycle. We help cyclists explore the landscapes and THE WONDROUS YUCATÁN by Charles Lynch history of America for fitness, fun, 20 Contrary to the fear others perceived, an American finds a hidden gem for bike touring. and self-discovery. CAMPAIGNS TAJIKISTAN IS FOR CYCLISTS by Rose Moore Our strategic plan includes three 26 If it’s rugged, spectacular bike travel that you seek, look no further than Central Asia. -

Stalking the Bamboo Bike by Joe Lapp December 2013

Stalking the Bamboo Bike by Joe Lapp December 2013 In an African country with few safari animals, what’s to pounce on instead? Locally grown two-wheelers. The first time I see Craig Calfee, creator of the carbon fiber bicycle and pioneer of the modern bamboo bike movement, he’s leaning out of a moving minivan in Ghana, West Africa, trying to get my attention. His gray curls dance as the van races toward a green left-turn arrow. His right arm waves madly from a torso stretched out of the careening van’s side-door window. He’s a man committed. I’d been standing on that corner – with West African practicality called Kaneshie First Light, the first stoplight after Kaneshie market – hoping he’d show. It’s not hard for two white guys in Ghana to find each other. Our meeting is a fluke, though Craig’s presence in Accra, Ghana’s coastal capital, is no accident. He’s checking up on Ghanaian bike builders he trained to make two-wheeled wonders from a plant. Yes, a plant. Africa. Name it and an American might think: starving babies, stark deserts, dense jungles, rebel groups high on drugs. The continent doesn’t often present itself as a center of innovative design fueling a green revolution. But if Craig Calfee has his way, that’s going to change. Ghana. Name the nation and the American looks thoughtful: here’s a country she knows she’s heard of, though she couldn’t place it on a map. Think famed West African slave castles. -

Upper Riccarton Cemetery 2007 1

St Peter’s, Upper Riccarton, is the graveyard of owners and trainers of the great horses of the racing and trotting worlds. People buried here have been in charge of horses which have won the A. J. C. Derby, the V.R.C. Derby, the Oaks, Melbourne Cup, Cox Plate, Auckland Cup (both codes), New Zealand Cup (both codes) and Wellington Cup. Area 1 Row A Robert John Witty. Robert John Witty (‘Peter’ to his friends) was born in Nelson in 1913 and attended Christchurch Boys’ High School, College House and Canterbury College. Ordained priest in 1940, he was Vicar of New Brighton, St. Luke’s and Lyttelton. He reached the position of Archdeacon. Director of the British Sailors’ Society from 1945 till his death, he was, in 1976, awarded the Queen’s Service Medal for his work with seamen. Unofficial exorcist of the Anglican Diocese of Christchurch, Witty did not look for customers; rather they found him. He said of one Catholic lady: “Her priest put her on to me; they have a habit of doing that”. Problems included poltergeists, shuffling sounds, knockings, tapping, steps tramping up and down stairways and corridors, pictures turning to face the wall, cold patches of air and draughts. Witty heard the ringing of Victorian bells - which no longer existed - in the hallway of St. Luke’s vicarage. He thought that the bells were rung by the shade of the Rev. Arthur Lingard who came home to die at the vicarage then occupied by his parents, Eleanor and Archdeacon Edward Atherton Lingard. In fact, Arthur was moved to Miss Stronach’s private hospital where he died on 23 December 1899. -

Reconnection to Cleared Site in Christchurch Architecture for the Rememberer

Reconnection to Cleared Site in Christchurch Architecture for the Rememberer Abigail Michelle Thompson A thesis submitted in ful! lment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture (professional), The University of Auckland, 2012 Fig 1: Project. Surface study model by author. Abstract The loss of life and buildings due to the devastating and continuing earthquakes in Canterbury (since 9th September, 2010) have created a need to examine the issue of memory with concerns to architecture in a New Zealand context. This thesis was initiated with concern to addressing the cleared (destroyed, demolished) buildings of Christchurch and architecture’s role in reconnecting Cantabrians mnemonically to the cleared sites in their city. This is an investigation of architecture’s ability to trigger memories in order to speci! cally address the disorientation experienced by Cantabrians subsequent to the loss of built fabric in their city. The design intention is to propose an architectural method for reconnecting people’s memories with site, which will have implications to other sites throughout the city of Christchurch. Consequently, two signi! cant sites of destruction have been chosen, the Methodist Church site at 309 Durham St (community) and the house at 69 Sherborne St (domestic). With the only original material left on these cleared sites being the ground itself, two issues were made apparent. Firstly, that ground should play a signi! cant role in substantiating the memory of the site(s), and secondly the necessary task of designing a mnemonic language without tangible links (other than ground). Collective memory is examined with regards to theory by Maurice Halbwachs, Piere Nora, and Peter Carrier. -

Tandems Owner’S Manual Supplement 116831.PDF Revision 2

READ THIS MANUAL CAREFULLY! It contains important safety information. Keep it for future reference. Tandems Owner’s Manual Supplement 116831.PDF Revision 2 CONTENTS GENERAL SAFETY INFORMATION ......... 2 TECHNICAL SECTION ............................12 About This Supplement ............................... 2 Stoker Handlebar System ...........................12 Special Manual Messages ........................... 2 About Tandem Forks ....................................13 Intended Use ................................................. 3 Brake Systems ...............................................13 Building Up A Frameset ............................... 3 Rim, Hydraulic and Rear Drum Brakes .....14 TANDEM RIDING ................................... 4 Timing Chain Tension ..................................12 The Captain’s Responsibility ....................... 4 Derailleur BB Cable Routing ......................15 The Stoker ........................................................ 5 Adjusting the Timing Chain .......................18 Tandem Bike Fit .............................................. 5 MAINTENANCE .................................... 22 Getting Underway ........................................6 GEOMETRY ........................................... 23 Starting Off .....................................................6 Stopping ..........................................................8 REPLACEMENT PARTS (KITS) .................25 Slow Speed Riding .........................................8 OWNER NOTES ................................... -

A History of the Barbadoes Street Cemetery

A HISTORY OF THE BARBADOES S~REE~ 0EMET}~Y. (A) IR~RODUCTION. ( 1) G·eneral. A brief note on the location, division and religious composition of' the three cemeteries, and the signif icance of the Cemetery in the history of Christchurch. (2) Early European Settlement of Canterbury. A brief note on the early settlement of Christchurch, Banks Peninsula and the ~lains prior to the arrival of the Canterbury Pilgrims. / (3) Edward Gibbon Wakefield and an. exclusive Church of England Settlement. A brief note on Wakefield's idea of an exclusive Church of England settlemen~ in Canterbury. (4) The Siting and Surveying of Christchurch. A brief note on the acquisition: of land in Canterbury, the siting and Surveying of Christchurch by Captain ~oseph Thomas and Edward Jollie, and the provision made for cemetery reserves. (5) The Canterbury Pilgrims. A brief note on the arrival of the Canterbury Pilgrims, /) their first impressions, conditions, religious . G. composition and numbers. j (B) THE THREE CEMETERIES. (1851 - 1885). /' j (1) General. if< ·rr::!.o~Ac..T1or,j (1 - d . A brief note on the Church of Bngland, Dissenter.and Roman Catholic religious developMents during the early years and the provision made for ~esbyterian burials. Early burials and undertakers. (2) The Setting-up and nevelopment of the 8emeteries • ./ (a) ,Church of England Gemetery• ./(i) The F..arl y V'ears. / (ii) The Construcciion of the Mortuary Chapel. .iii) Consecreation of the Cemetery. j (iv) The Setting-up of the I;emetery Board. / (v) Rules and Regulations. ~ (vi) The laying out, boundaries, plans, registers and maintenance of the r;emetery, and extensions to the Cemetery. -

Cortes Island

Accommodation Shops & Groceries Restaurants & Cafes Barbara’s B&B Cortes Market Cortes Natural Food Co-op Bakery & Cafe 14 250.935.6383 ~ www.cortesislandbandb.com 23 250.935.6626 ~ www.cortesmarket.com 32 250.935.6505 ~ www.cortescoop.ca Deluxe, full organic breakfast. Homemade breads, Located in uptown Manson’s. Largest selection on the Meet up, hang out, and get food! We offer espresso pastries, jams. Private entrance and patio. Water view. island for groceries and produce. drinks, breakfast, and lunch along with fresh bread and baked treats using local and natural ingredients. Fully licensed, seating Brilliant by the Bay Bed & Breakfast Cortes Natural Food Co-op inside and out. Call for hours as they vary with the seasons. 15 250.935.0022 ~ www.brillbybay.com 24 250.935.8577 ~ www.cortescoop.ca Located on the island’s sunny south end. The Co-op brings Cortes Island farmers, fishers and The Cove Restaurant foodies straight to your table! We feature fresh, local, and organic 33 250.935.6350 ~ www.squirrelcove.com Cortes Island Boathouse products, including produce, dairy, meat, seafood, and a full Relax in the comfort of our casual dining room or on our 16 250.935.6795 ~ www.cortesislandboathouse.com selection of other eco-friendly food items. Everyone welcome! fabulous deck with spectacular views overlooking world famous Waterfront accommodation at the high tide line. Stunning Desolation Sound. Delicious fresh and varied menu with coastal mountain/ocean views. Perfect honeymoon or family holiday! Dandy Horse Bikes flavours. Daily specials and take out service. Licensed. 25 250.857.3520 ~ www.dandyhorsebikes.ca Cortes Island Motel Dandy Horse exists to serve the Cortes cycling 17 250.935.6363 ~ www.cortesislandmotel.com community. -

Blade Propelled Bicycle Shitansh Jain1, Mayur Bidwe2, Samrudhi Godse3, Gaurang Patil4 and Manoj Patil5

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 07 Issue: 07 | July 2020 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Blade Propelled Bicycle Shitansh Jain1, Mayur Bidwe2, Samrudhi Godse3, Gaurang Patil4 and Manoj Patil5 1-4Student, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, KBTCOE, Nashik, Maharashtra, India; 5Professor, Dept. of Mechanical Engineering, KBTCOE, Nashik, Maharashtra, India; ---------------------------------------------------------------------***---------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - The world today heavily relies on fossil fuels for and commuter cyclists has grown. For those groups, the power consumption. It is only a matter of time that fossil fuels industry responded with the hybrid bicycle, occasionally will be completely used up and no longer available. In such advertised as a town bike, cross bike, or commuter bike. scenario, riding a bicycle is the best suitable option to go from Hybrid bicycles combine factors of avenue racing and one place to another. An alternative to this is the electric mountain bikes, even though the term is applied to a wide bicycles which have greater speed and require less effort to variety of bicycle types. ride the bicycle. Also there are some research papers on motion of bicycle with the help of compressed air. Contrary, to By 2007, e-motorcycles were notion to make up ten to already existing technology, the purpose of this research is to twenty percent of all two-wheeled vehicles at the street of get boosted power (thrust). The research mainly involves many primary Chinese localities. A standard unit requires 8 designing the bicycle frame and giving it electrical power hours to rate the battery, which offers the variety of 25 to 30 support for motion of the structure with the help of batteries, miles, at a speed of 20km/h. -

Kewanee's Love Affair with the Bicycle

February 2020 Kewanee’s Love Affair with the Bicycle Our Hometown Embraced the Two-Wheel Mania Which Swept the Country in the 1880s In 1418, an Italian en- Across Europe, improvements were made. Be- gineer, Giovanni Fontana, ginning in the 1860s, advances included adding designed arguably the first pedals attached to the front wheel. These became the human-powered device, first human powered vehicles to be called “bicycles.” with four wheels and a (Some called them “boneshakers” for their rough loop of rope connected by ride!) gears. To add stability, others experimented with an Fast-forward to 1817, oversized front wheel. Called “penny-farthings,” when a German aristo- these vehicles became all the rage during the 1870s crat and inventor, Karl and early 1880s. As a result, the first bicycle clubs von Drais, created a and competitive races came into being. Adding to two-wheeled vehicle the popularity, in 1884, an Englishman named known by many Thomas Stevens garnered notoriety by riding a names, including Drais- bike on a trip around the globe. ienne, dandy horse, and Fontana’s design But the penny-farthing’s four-foot high hobby horse. saddle made it hazardous to ride and thus was Riders propelled Drais’ wooden, not practical for most riders. A sudden 50-pound frame by pushing stop could cause the vehicle’s mo- off the ground with their mentum to send it and the rider feet. It didn’t include a over the front wheel with the chain, brakes or pedals. But rider landing on his head, because of his invention, an event from which the Drais became widely ack- Believed to term “taking a header” nowledged as the father of the be Drais on originated. -

Julius Haast Towards a New Appreciation of His Life And

JULIUS HAAST TOWARDS A NEW APPRECIATION OF HIS LIFE AND WORK __________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury by Mark Edward Caudel University of Canterbury 2007 _______ Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... i List of Plates and Figures ...................................................................................... ii Abstract................................................................................................................. iii Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 Chapter 2: Who Was Julius Haast? ...................................................................... 10 Chapter 3: Julius Haast in New Zealand: An Explanation.................................... 26 Chapter 4: Julius Haast and the Philosophical Institute of Canterbury .................. 44 Chapter 5: Julius Haast’s Museum ....................................................................... 57 Chapter 6: The Significance of Julius Haast ......................................................... 77 Chapter 7: Conclusion.......................................................................................... 86 Bibliography ......................................................................................................... 89 Appendices ..........................................................................................................