Evaluating the "Salesmanship" of the Vietnam War in 1967 Gregory A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US Army Was Already Upset About Its Losses from Deep Personnel and White House Photo Via National Archives Budget Cuts When Gen

National Park Service photo by Abbie Rowe By John T. Correll US Army was already upset about its losses from deep personnel and White House photo via National Archives budget cuts when Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor arrived as the new Chief of Defense Technical Information Center photo Staff in June 1955. Army strength was down by almost a third since the Korean War and the Army share of the budget was dropping steadily. These reductions were the result of the “New Look” defense program, introduced in 1953 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and the “Massive Retaliation” strategy that went with it. New Look was focused on the threat of Soviet military power, putting greater reliance on strategic airpower and nuclear weapons and less emphasis on the kind of wars the Army fought. US planning was based on the standard of general war; the limited conflict in Korea was regarded as an aberration. If for some reason another small or limited war had to be fought, the US armed forces, organized and equipped for general war, would handle it as a “lesser included contingency.” New Look—so called because Eisenhower had ordered a “new fresh survey of our military capabilities”—was driven by the belief that adequate security was possible at lower cost, especially if general purpose forces overseas were thinned out. Another factor was the recognition that NATO could not match the con- ventional forces of the Soviet Union, which had 175 divisions—30 of them in Europe—and 6,000 aircraft based forward. So in 1952, the US and its allies had adopted a strategy centered on a nuclear response to attack. -

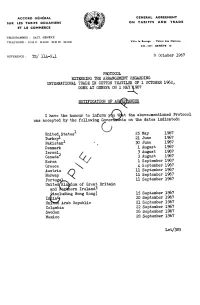

9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING the ARRANGEMENT

ACCORD GÉNÉRAL GENERAL AGREEMENT SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ON TARIFFS AND TRADE ET LE COMMERCE m TELEGRAMMES : GATT, GENÈVE TELEPHONE: 34 60 11 33 40 00 33 20 00 3310 00 Villa le Bocage - Palais des Nations CH-1211 GENÈVE tO REFERENCE : TS/ 114--5*! 9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING THE ARRANGEMENT REGARDING INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN COTTON TEXTILES OF 1 OCTOBER 1962, DONE AT GENEVA ON 1 MAY U967 NOTIFICATION OF ACCEPTANCES I have the honour to inform yew. tHat the above-mentioned Protocol was accepted by the following Governments on the dates indicated: United States G 25 May 1967 Turkeys- 21 June 1967 Pakistan 30 June 1967 Denmark 1 August 1967 Israel, 3 August 1967 Canada* 3 August 1967 Korea 1 September 1967 Greece U September 1967 Austria 11 September 1967 Norway 11 September 1967 Portuga 11 Septembei• 1967 United/kinkdom of Great Britain and ItacAnern Ireland^ ^including Hong Kong) 15 September 1967 Irttia^ 20 September 1967 Unrtrea Arab Republic 21 September 1967 Colombia 22 September 1967 Sweden 26 September 1967 Mexico 28 September 1967 Let/385 - 2 - Republic of China 28 September 1967 Finland 29 September 1967 Belgium 29 September 1967 France 29 September 1967 Germany, Federal Republic 29 September 1967 Italy 29 September 1967 Luxemburg 29 September 1967 Netherlands, Kingdom of the (for its European territory only) 29 September 1967 Japan ,. 30 September 1967 Australia 30 September 1967 Jamaica 2 October 1967 Spain 3 October 1967 Acceptance by the Governments of Italy and of the Federal Republic of Germany was made subject to ratification. The Protocol entered into force on 1 October 1967, pursuant to its paragraph 5. -

The Pulitzer Prizes for International Reporting in the Third Phase of Their Development, 1963-1977

INTRODUCTION THE PULITZER PRIZES FOR INTERNATIONAL REPORTING IN THE THIRD PHASE OF THEIR DEVELOPMENT, 1963-1977 Heinz-Dietrich Fischer The rivalry between the U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. having shifted, in part, to predomi- nance in the fields of space-travel and satellites in the upcoming space age, thus opening a new dimension in the Cold War,1 there were still existing other controversial issues in policy and journalism. "While the colorful space competition held the forefront of public atten- tion," Hohenberg remarks, "the trained diplomatic correspondents of the major newspa- pers and wire services in the West carried on almost alone the difficult and unpopular East- West negotiations to achieve atomic control and regulation and reduction of armaments. The public seemed to want to ignore the hard fact that rockets capable of boosting people into orbit for prolonged periods could also deliver atomic warheads to any part of the earth. It continued, therefore, to be the task of the responsible press to assign competent and highly trained correspondents to this forbidding subject. They did not have the glamor of TV or the excitement of a space shot to focus public attention on their work. Theirs was the responsibility of obliging editors to publish material that was complicated and not at all easy for an indifferent public to grasp. It had to be done by abandoning the familiar cliches of journalism in favor of the care and the art of the superior historian .. On such an assignment, no correspondent was a 'foreign' correspondent. The term was outdated. -

Cy Martin Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Cy Martin Collection Martin, Cy (1919–1980). Papers, 1966–1975. 2.33 feet. Author. Manuscripts (1968) of “Your Horoscope,” children’s stories, and books (1973–1975), all written by Martin; magazines (1966–1975), some containing stories by Martin; and biographical information on Cy Martin, who wrote under the pen name of William Stillman Keezer. _________________ Box 1 Real West: May 1966, January 1967, January 1968, April 1968, May 1968, June 1968, May 1969, June 1969, November 1969, May 1972, September 1972, December 1972, February 1973, March 1973, April 1973, June 1973. Real West (annual): 1970, 1972. Frontier West: February 1970, April 1970, June1970. True Frontier: December 1971. Outlaws of the Old West: October 1972. Mental Health and Human Behavior (3rd ed.) by William S. Keezer. The History of Astrology by Zolar. Box 2 Folder: 1. Workbook and experiments in physiological psychology. 2. Workbook for physiological psychology. 3. Cagliostro history. 4. Biographical notes on W.S. Keezer (pen name Cy Martin). 5. Miscellaneous stories (one by Venerable Ancestor Zerkee, others by Grandpa Doc). Real West: December 1969, February 1970, March 1970, May 1970, September 1970, October 1970, November 1970, December 1970, January 1971, May 1971, August 1971, December 1971, January 1972, February 1972. True Frontier: May 1969, September 1970, July 1971. Frontier Times: January 1969. Great West: December 1972. Real Frontier: April 1971. Box 3 Ford Times: February 1968. Popular Medicine: February 1968, December 1968, January 1971. Western Digest: November 1969 (2 copies). Golden West: March 1965, January 1965, May 1965 July 1965, September 1965, January 1966, March 1966, May 1966, September 1970, September 1970 (partial), July 1972, August 1972, November 1972, December 1972, December 1973. -

The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945-1965

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Publications Communication, College of 9-1-2018 The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945-1965 Gregory R. Olson Marquette University George N. Dionisopoulos San Diego State University Steven R. Goldzwig Marquette University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/comm_fac Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Olson, Gregory R.; Dionisopoulos, George N.; and Goldzwig, Steven R., "The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945-1965" (2018). College of Communication Faculty Research and Publications. 511. https://epublications.marquette.edu/comm_fac/511 The Rhetorical Antecedents to Vietnam, 1945–1965 Gregory A. Olson, George N. Dionisopoulos, and Steven R. Goldzwig 8 I do not believe that any of the Presidents who have been involved with Viet- nam, Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, or President Nixon, foresaw or desired that the United States would become involved in a large scale war in Asia. But the fact remains that a steady progression of small decisions and actions over a period of 20 years had forestalled a clear-cut decision by the President or by the President and Congress—decision as to whether the defense of South Vietnam and involvement in a great war were necessary to the security and best interest of the United States. —Senator John Sherman Cooper (R-KY), Congressional Record, 1970 n his 1987 doctoral thesis, General David Petraeus wrote of Vietnam: “We do not take the time to understand the nature of the society in which we are f ght- Iing, the government we are supporting, or the enemy we are f ghting.”1 After World War II, when the United States chose Vietnam as an area for nation building as part of its Cold War strategy, little was known about that exotic land. -

OCTOBER, 1967 Copied from an Original at the History Center

Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 OCTOBER, 1967 Copied from an original at The History Center. www.TheHistoryCenterOnline.com 2013:023 rom the PRESIDENT'S DESK ... Fellow Employees: There is a certain quality in some people which makes them a good team member whether it be at play or in th e workshop. This quality is usually inherent in a Winner. In a football game, th e coach would call it " team spirit." On the school campus, th e student or professor refers to it as "school pride." Jn th e armed services, the soldier or sailor expresses it as a phrase called "esprit de Corps." But in this work-a-day world, it is merely called " loyalty." On the wall in Mutt Barr's office is a plaque containing these famous words by Elbert Hubbard: "If you work for a man, in heaven's name work for him; Speak well of him and stand by the institution he represents. Remember, an ounce of loyalty is worth a pound of clever- ness. If you must growl, condemn and enternally find fault, why re ign your position. And when you are outside, damn to your heart's content But as long as you are part of the institution do not con demn it. If you do, the first high wind that comes along will blow you away and probably yo u will never know why." I don't believe there is another quality more important to the success of an organization than the loyalty of its employees. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Beil & Howell Iniormation Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313,761-4700 800,521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

The Two Koreas: Revised and Updated a Contemporary History

[PDF] The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Don Oberdorfer - download pdf The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History PDF Download, Download The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History PDF, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Download PDF, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History by Don Oberdorfer Download, PDF The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Popular Download, Read Best Book Online The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History, I Was So Mad The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Don Oberdorfer Ebook Download, PDF The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Free Download, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Free Read Online, read online free The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Don Oberdorfer pdf, Don Oberdorfer epub The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History, pdf Don Oberdorfer The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History, Download The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Online Free, Read Best Book Online The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History, Read The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Books Online Free, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Ebooks Free, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Read Download, The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Free PDF Online, Free Download The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Books [E-BOOK] The Two Koreas: Revised And Updated A Contemporary History Full eBook, CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD The historic cash animal. -

Inside the News

News. Society of National Association Publications - Award Winning Newspaper Published by the Association of the U.S. Army VOLUME 42 NUMBER 2 www.ausa.org December 2018 Inside the News 2018 Annual Meeting Award Presentations – 9, 12 to 16 – New Army Uniform – 2 – Piggee on Logistics – 2 – AUSA Family Readiness Building a Battle Plan – 3 – AUSA Book Program Secret War in Laos – 6 – Capitol Focus New Army Vets in Congress – 10 – Future Vertical Lift – 10 – Synthetic Training Environment – 21 – Chapter Highlights Redstone-Huntsville 3 NCOs Honored – 18 – Charleston VA Nurse Honored – 21 – Sniper teams from across the globe travelled to Fort Benning, Ga., to compete Robert E. Lee in the Annual International Sniper Competition. The goal of this competition Vietnam War Anniversary is to identify the best sniper team from a wide range of agencies and organiza- – 22 – tions that includes the U.S. military, international militaries, and local, state and federal law enforcement. (Photo by Master Sgt. Michel Sauret) Redstone-Huntsville The Wall That Heals See NCO Report on Page 8 – 24 – 2 AUSA NEWS q December 2018 ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY Piggee: Command maintenance, supply discipline are essential AUSA Staff In the past two years, the Army has regained its footing with improvements in the supply of spare he Army’s ability to sustain itself in an aus- parts across the Army and standardized brigade tere environment against a capable adversary combat team supply stockage, which has resulted in Twill depend on leveraging today’s technol- more weapon system repairs in forward locations. ogy more quickly, the Army’s chief logistician says. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

(D91e214) Pdf Patriots: the Vietnam War Remembered from All

pdf Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered From All Sides Christian G. Appy - free pdf download Read Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Full Collection Christian G. Appy, Download Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides E-Books, pdf free download Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides, online free Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides, Read Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Books Online Free, Read Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Ebook Download, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Download PDF, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides PDF Download, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Christian G. Appy pdf, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides PDF read online, pdf Christian G. Appy Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides, book pdf Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Free Download, free online Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides, Download Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Online Free, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Free PDF Download, Pdf Books Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Full Collection, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides PDF Download, Read Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides Full Collection Christian G. Appy, CLICK HERE - DOWNLOAD epub, azw, kindle,