Berry, Richard (2013) Radio with Pictures: Radio Visualization in BBC National Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music-Week-1993-05-0

4 Morechoice 8 Town crier 10 Wisdom Kenyon'smaintain vowR3's to Take This Town Vintage comic is musical range visitsCroydon the streets active Marketsurprise Preview star of ■ ^ • H itmsKweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 1 MAY 1993 £2.65 iiistargetCO mftl17 Adestroy forced the eut foundationsin CD prices ofcould the half-hourtives were grillinggiven a lastone-and-a- week. wholeliamentary music selectindustry, committee the par- MalcolmManaging Field, director repeating hisSir toldexaraining this week. CD pricing will be reducecall for dealer manufacturers prices by £2,to twoSenior largest executives and two from of the "cosy"denied relationshipthat his group with had sup- a thesmallest UK will record argue companies that pricing in pliera and defended its support investingchanges willin theprevent new talentthem RichardOur Price Handover managing conceded director thatleader has in mademusic. the UK a world Kaufman adjudicates (centre) as Perry (left) and Ames (right) head EMI and PolyGram délégations atelythat his passed chain hadon thenot immedi-reduced claimsTheir alreadyarguments made will at echolast businesspeople rather without see athose classical fine Tradingmoned. has also been sum- industryPrivately profitability. witnesses who Warnerdealer Musicprice inintroduced 1988. by Goulden,week's hearing. managing Retailer director Alan of recordingsdards for years that ?" set the stan- RobinTemple Morton, managing whose director label othershave alreadyyet to appearedappear admit and managingIn the nextdirector session BrianHMV Discountclassical Centre,specialist warned Music the tionThe was record strengthened companies' posi-last says,spécialisés "We're intrying Scottish to put folk, out teedeep members concem thatalready the commit-believe lowerMcLaughlin prices saidbut addedhe favoured HMV thecommittee music against industry singling for outa independentsweek with the late inclusionHyperion of erwise.music that l'm won't putting be heard oth-out CDsLast to beweek overpriced, committee chair- hadly high" experienced CD sales. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Technical Specification

ETSI TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Technical Specification Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB); MOT SlideShow; User Application Specification European Broadcasting Union Union Européenne de Radio-Télévision EBU·UER 2 ETSI TS 101 499 V2.2.1 (2008-07) Reference RTS/JTC-DAB-57 Keywords audio, broadcasting, DAB, digital, PAD ETSI 650 Route des Lucioles F-06921 Sophia Antipolis Cedex - FRANCE Tel.: +33 4 92 94 42 00 Fax: +33 4 93 65 47 16 Siret N° 348 623 562 00017 - NAF 742 C Association à but non lucratif enregistrée à la Sous-Préfecture de Grasse (06) N° 7803/88 Important notice Individual copies of the present document can be downloaded from: http://www.etsi.org The present document may be made available in more than one electronic version or in print. In any case of existing or perceived difference in contents between such versions, the reference version is the Portable Document Format (PDF). In case of dispute, the reference shall be the printing on ETSI printers of the PDF version kept on a specific network drive within ETSI Secretariat. Users of the present document should be aware that the document may be subject to revision or change of status. Information on the current status of this and other ETSI documents is available at http://portal.etsi.org/tb/status/status.asp If you find errors in the present document, please send your comment to one of the following services: http://portal.etsi.org/chaircor/ETSI_support.asp Copyright Notification No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. -

Replacing Digital Terrestrial Television with Internet Protocol?

This is a repository copy of The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94851/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Ala-Fossi, M and Lax, S orcid.org/0000-0003-3469-1594 (2016) The short future of public broadcasting: Replacing digital terrestrial television with internet protocol? International Communication Gazette, 78 (4). pp. 365-382. ISSN 1748-0485 https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048516632171 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Short Future of Public Broadcasting: Replacing DTT with IP? Marko Ala-Fossi & Stephen Lax School of Communication, School of Media and Communication Media and Theatre (CMT) University of Leeds 33014 University of Tampere Leeds LS2 9JT Finland UK [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Public broadcasting, terrestrial television, switch-off, internet protocol, convergence, universal service, data traffic, spectrum scarcity, capacity crunch. -

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa Radio is by far the dominant and most important mass medium in Africa. Its flexibility, low cost, and oral character meet Africa's situation very well. Yet radio is less developed in Africa than it is anywhere else. There are relatively few radio stations in each of Africa's 53 nations and fewer radio sets per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Radio remains the top medium in terms of the number of people that it reaches. Even though television has shown considerable growth (especially in the 1990s) and despite a widespread liberalization of the press over the same period, radio still outstrips both television and the press in reaching most people on the continent. The main exceptions to this ate in the far south, in South Africa, where television and the press are both very strong, and in the Arab north, where television is now the dominant medium. South of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo River, radio remains dominant at the start of the 21St century. The internet is developing fast, mainly in urban areas, but its growth is slowed considerably by the very low level of development of telephone systems. There is much variation between African countries in access to and use of radio. The weekly reach of radio ranges from about 50 percent of adults in the poorer countries to virtually everyone in the more developed ones. But even in some poor countries the reach of radio can be very high. In Tanzania, for example, nearly nine out of ten adults listen to radio in an average week. -

Warburton, John Henry. (2010). Picture Radio

! ∀# ∃ !∃%& ∋ ! (()(∗( Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? John Henry Warburton Master of Philosophy Southampton Solent University Faculty of Media, Arts and Society July 2010 Tutor Mike Richards 3 of 3 Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? By John Henry Warburton Abstract This work looking at radio over the last 80 years and digital radio today will consider picture radio, one way that the recently introduced DAB1 terrestrial digital radio could be used. Chapter one considers the radio history including early picture radio and television, plus shows how radio has come from the crystal set, with one pair of headphones, to the mains powered wireless with built in speakers. These radios became the main family entertainment in the home until television takes over that role in the mid 1950s. Then radio changed to a portable medium with the coming of transistor radios, to become the personal entertainment medium it is today. Chapter two and three considers the new terrestrial digital mediums of DAB and DRM2 plus how it works, what it is capable of plus a look at some of the other digital radio platforms. Chapter four examines how sound is perceived by the listener and that radio broadcasters will need to understand the relationship between sound and vision. We receive sound and then make pictures in the mind but to make sense of sound we need codes to know what it is and make sense of it. Chapter five will critically examine the issues of commercial success in radio and where pictures could help improve the radio experience as there are some things that radio is restricted to as a sound only medium. -

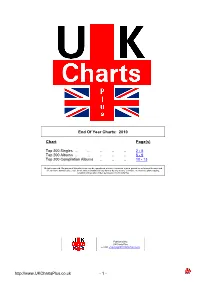

End of Year Charts: 2010

End Of Year Charts: 2010 Chart Page(s) Top 200 Singles .. .. .. .. .. 2 - 5 Top 200 Albums .. .. .. .. .. 6 - 9 Top 200 Compilation Albums .. .. .. 10 - 13 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, posted on an Internet/Intranet web site or forum, forwarded by email, or otherwise transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording without prior written permission of UKChartsPlus Published by: UKChartsPlus e-mail: [email protected] http://www.UKChartsPlus.co.uk - 1 - Symbols: Platinum (600,000) Gold (400,000) Silver (200,000) 12” Vinyl only 2010 7” Vinyl only Download only Entry Date 2010 2009 2008 2007 Title - Artist Label (Cat. No.) (w/e) High Wks 1 -- -- -- LOVE THE WAY YOU LIE - Eminem featuring Rihanna Interscope (2748233) 03/07/2010 2 28 2 -- -- -- WHEN WE COLLIDE - Matt Cardle Syco (88697837092) 25/12/2010 13 3 3 -- -- -- JUST THE WAY YOU ARE (AMAZING) - Bruno Mars Elektra ( USAT21001269) 02/10/2010 12 15 4 -- -- -- ONLY GIRL (IN THE WORLD) - Rihanna Def Jam (2755511) 06/11/2010 12 10 5 -- -- -- OMG - Usher featuring will.i.am LaFace ( USLF20900103) 03/04/2010 1 41 6 -- -- -- FIREFLIES - Owl City Island ( USUM70916628) 16/01/2010 13 51 7 -- -- -- AIRPLANES - B.o.B featuring Hayley Williams Atlantic (AT0353CD) 12/06/2010 1 31 8 -- -- -- CALIFORNIA GURLS - Katy Perry featuring Snoop Dogg Virgin (VSCDT2013) 03/07/2010 12 28 WE NO SPEAK AMERICANO - Yolanda Be Cool vs D Cup 9 -- -- -- 17/07/2010 1 26 All Around The World/Universal -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

Through the Iris TH Wasteland SC Because the Night MM PS SC

10 Years 18 Days Through The Iris TH Saving Abel CB Wasteland SC 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10,000 Maniacs 1,2,3 Redlight SC Because The Night MM PS Simon Says DK SF SC 1975 Candy Everybody Wants DK Chocolate SF Like The Weather MM City MR More Than This MM PH Robbers SF SC 1975, The These Are The Days PI Chocolate MR Trouble Me SC 2 Chainz And Drake 100 Proof Aged In Soul No Lie (Clean) SB Somebody's Been Sleeping SC 2 Evisa 10CC Oh La La La SF Don't Turn Me Away G0 2 Live Crew Dreadlock Holiday KD SF ZM Do Wah Diddy SC Feel The Love G0 Me So Horny SC Food For Thought G0 We Want Some Pussy SC Good Morning Judge G0 2 Pac And Eminem I'm Mandy SF One Day At A Time PH I'm Not In Love DK EK 2 Pac And Eric Will MM SC Do For Love MM SF 2 Play, Thomas Jules And Jucxi D Life Is A Minestrone G0 Careless Whisper MR One Two Five G0 2 Unlimited People In Love G0 No Limits SF Rubber Bullets SF 20 Fingers Silly Love G0 Short Dick Man SC TU Things We Do For Love SC 21St Century Girls Things We Do For Love, The SF ZM 21St Century Girls SF Woman In Love G0 2Pac 112 California Love MM SF Come See Me SC California Love (Original Version) SC Cupid DI Changes SC Dance With Me CB SC Dear Mama DK SF It's Over Now DI SC How Do You Want It MM Only You SC I Get Around AX Peaches And Cream PH SC So Many Tears SB SG Thugz Mansion PH SC Right Here For You PH Until The End Of Time SC U Already Know SC Until The End Of Time (Radio Version) SC 112 And Ludacris 2PAC And Notorious B.I.G. -

The Meaning of Katrina Amy Jenkins on This Life Now Judi Dench

Poor Prince Charles, he’s such a 12.09.05 Section:GDN TW PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 11/9/2005 17:09 troubled man. This time it’s the Back page modern world. It’s all so frenetic. Sam Wollaston on TV. Page 32 John Crace’s digested read Quick Crossword no 11,030 Title Stories We Could Tell triumphal night of Terry’s life, but 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Author Tony Parsons instead he was being humiliated as Dag and Misty made up to each other. 8 Publisher HarperCollins “I’m going off to the hotel with 9 10 Price £17.99 Dag,” squeaked Misty. “How can you do this to me?” Terry It was 1977 and Terry squealed. couldn’t stop pinching “I am a woman in my own right,” 11 12 himself. His dad used to she squeaked again. do seven jobs at once to Ray tramped through the London keep the family out of night in a daze of existential 13 14 15 council housing, and here navel-gazing. What did it mean that he was working on The Elvis had died that night? What was 16 17 Paper. He knew he had only been wrong with peace and love? He wound brought in because he was part of the up at The Speakeasy where he met 18 19 20 21 new music scene, but he didn’t care; the wife of a well-known band’s tour his piece on Dag Wood, who uncannily manager. “Come back to my place,” resembled Iggy Pop, was on the cover she said, “and I’ll help you find John 22 23 and Misty was by his side. -

Commissioning Brief

RADIO COMMISSIONING FRAMEWORK Commissioning Brief Commissioning Brief No: 107001 Production of BBC Radio 5 Live’s new ‘Sport Entertainment’ podcast for BBC Sounds CONTENTS SECTION A: EDITORIAL OPPORTUNITY........................................................................... 3 SECTION B: THE COMMISSIONING PROCESS ................................................................. 8 1. TIMETABLE .......................................................................................................... 8 2. THE FIVE STAGES ................................................................................................. 9 3. ASSESSMENT CRITERIA ..................................................................................... 11 SECTION C: FULL PROPOSALS ...................................................................................... 12 1. WHAT WE NEED FROM YOU ............................................................................. 12 2. WHAT TO EXPECT FROM US ............................................................................. 13 3. IMPORTANT POINTS TO NOTE .......................................................................... 14 SECTION D: KEY CONTRACT TERMS…………………………………………………………………………15 2 of 15 SECTION A: EDITORIAL OPPORTUNITY Commissioning Brief 107001 Sports Entertainment Podcast Commission contact Richard Maddock Duration Average 30-60 minutes per episode Number of programmes available Minimum initial run of 15 eps with option to extend. Transmission period Starting early 2020 Guide price per episode £2k -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.