The Illusory Distinction Between Lexical and Encyclopedic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Words of the World: a Global History of the Oxford English Dictionary

DOWNLOAD CSS Notes, Books, MCQs, Magazines www.thecsspoint.com Download CSS Notes Download CSS Books Download CSS Magazines Download CSS MCQs Download CSS Past Papers The CSS Point, Pakistan’s The Best Online FREE Web source for All CSS Aspirants. Email: [email protected] BUY CSS / PMS / NTS & GENERAL KNOWLEDGE BOOKS ONLINE CASH ON DELIVERY ALL OVER PAKISTAN Visit Now: WWW.CSSBOOKS.NET For Oder & Inquiry Call/SMS/WhatsApp 0333 6042057 – 0726 540316 Words of the World Most people think of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) as a distinctly British product. Begun in England 150 years ago, it took more than 60 years to complete, and when it was finally finished in 1928, the British prime minister heralded it as a ‘national treasure’. It maintained this image throughout the twentieth century, and in 2006 the English public voted it an ‘Icon of England’, alongside Marmite, Buckingham Palace, and the bowler hat. But this book shows that the dictionary is not as ‘British’ as we all thought. The linguist and lexicographer, Sarah Ogilvie, combines her insider knowledge and experience with impeccable research to show that the OED is in fact an international product in both its content and its making. She examines the policies and practices of the various editors, applies qualitative and quantitative analysis, and finds new OED archival materials in the form of letters, reports, and proofs. She demonstrates that the OED,in its use of readers from all over the world and its coverage of World English, is in fact a global text. sarah ogilvie is Director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre, Reader in Linguistics at the Australian National University, and Chief Editor of Oxford Dictionaries, Australia. -

The Blueprints of Definition in Technical Dictionary

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 108 Social Sciences, Humanities and Economics Conference (SoSHEC 2017) The Blueprints of Definition in Technical Dictionary Fitri Amilia Kisyani Laksono Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra UniversitasNegeri Surabaya UniversitasNegeri Surabaya Surabaya, Indonesia Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] Budinuryanta Yohanes Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra UniversitasNegeri Surabaya Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Definition which refers to the term concept with Numbers of norms are considered in the conception of different formation of the form of specific words in a dictionary lemma. First, based on the argument of Lanur [1], Sudibya [2] has been the reason of the study. Collected data were in the form and Mundiri [3] it is the semantic consideration which rules the of definian taken from document record, identification and features to include or cover in the concept. Those features are classification of the norms found in the dictionaries. The data the term concepts which will differ the meaning of a term when collection technique was documentation done through note it is used in different context. These must be shortly and clearly taking, identification, and classification of the definiandum written. This norm shows the importance of semantic in formats. The data analysis was content analysis, similarities and defining lemma in a dictionary, and Ogden and Richards argue distributions of the definian. The result of the study shows that this will be completed through understanding the semantic patterns of genus definition and differentia, synonymous, triangle [4]. antonymous, negation, and broad and narrow, collocations, dual and multi, circular, context-bounded and context-unbounded, Another important norm is called contextual norms. -

Words and Phrases Guide

ACT Parliamentary Counsel’s Office WWoorrddss aanndd PPhhrraasseess GGuuiiddee A Guide to Plain Legal Language December 2016 The ACT Parliamentary Counsel’s Office has endeavoured to ensure that the material in this guide is as accurate as possible. If you believe that this guide contains copyrighted work in a way that constitutes a copyright infringement, or if you are a copyright owner who is not appropriately acknowledged in this guide, please tell us so that we can make the necessary corrections. We may be contacted at [email protected] Contents Page Some thoughts iv How to use this guide v Classification of entries viii References xxiii Alphabetical list of words and phrases A–W Use of figures Other–1 Words and Phrases: A Guide to Plain Legal Language December 2016 iii Some thoughts ‘Make everything as simple as possible—but no more simple than that.’ Albert Einstein ‘(L)aws are not abstract propositions. They are expressions of policy arising out of specific situations and addressed to the attainment of particular ends.’ Justice Felix Frankfurter ‘The main aim of communication is clarity and simplicity. Usually they go together— but not always. ‘Communication is always understood in the context and experience of the receiver—- no matter what was intended. ‘If unnecessary things add to clarity or simplicity they should be retained.’ Edward De Bono ‘Legislation should be written so that it is feasible for the ordinary person of ordinary intelligence and ordinary education to have a reasonable expectation of understanding and comprehending legislation and of getting the answers to the questions he or she has. -

Chapter 02 Test A

MULTIPLE CHOICE 1 : Which of the following statements has primarily cognitive meaning? A : Private insurance companies regularly overbill the Medicare program. B : From what I saw last night, its clear that your little brother is a brat. C : Justin Timberlakes latest CD is positively stunning. D : Professor Gibson delivered a moronic lecture today on Platos metaphysics. E : Everyone with a functioning brain rejects religious fundamentalism. Correct Answer : A 2 : Which of the following statements expresses a value claim? A : Animal rights groups argue that live animals should not be used as mascots. B : The recent jobs report raised fears of a recession among Wall Street investors. C : Piracy continues to be a drag on the motion picture industry. D : The Los Angeles Times is a better paper than the San Francisco Chronicle. E : Diabetes poses a serious threat to the health of the elderly. Correct Answer : D 3 : Which of the following statements is vague? A : Tahiti is located in French Polynesia. B : American workers are more productive than the workers in any other country. C : Art work at the Genesis gallery tends to be expensive. D : Mabel shot her husband while taking a bath. E : Polar bears are threatened by global warming. Correct Answer : C 4 : Which of the following statements is ambiguous? A : Anniversaries are usually occasions for celebration. B : Homes in the new River Front development are reasonably priced. C : The Thanksgiving holiday always occurs in November. D : Boalt Hall is part of the University of California. E : Professor Hays talked about sex in the seminar room. -

Grammatical Information in Dictionaries: How Categorical Should It Be?

Colin Yallop, Macquarie University Grammatical Information in Dictionaries: How Categorical should it be? Abstract Dictionaries vary in their presentation of grammatical information but agree in assigning words to discrete grammatical categories, or at least in implying such assignment. But linguists like Halliday and Sinclair have argued that grammar is probabilistic rather than categorical. Corpus evidence shows that it is indeed more realistic to describe typical patterns than to insist on categorisation. Carefully chosen examples can signal typical usage without the need for rigid categorisation. 1. Introduction This paper draws on research into grammar and lexis carried out at Macquarie University by Emeritus Professor Ruqaiya Hasan, Dr Carmel Cloran and myself, supported by the Australian Research Council and by the Macquarie University Research Grant scheme. The paper also makes use of data from the Macquarie Dictionary corpus of Australian English, known as Ozcorp, made available by Macquarie Library Pty Ltd, the publishers of the dictionary. Most of the examples are verbs of saying: these verbs illustrate complex patterning of a kind that is elusive, to lexicographers and to users and learners of the language. 2. Current practice in presenting grammatical information Dictionaries vary in their presentation of grammatical information but agree in assigning words to discrete grammatical categories, or at least in implying such assignment. The Macquarie, for example, is relatively conservative, confining itself to category labels such as n., v.i. and v.t. Thus, say has entries not only as v.i. and v.t. but also as n., because of uses like it is now my say. Some dictionaries, especially those intended for advanced learners, give more elaborate grammatical information. -

A Study Guide by Katy Marriner

Based on the television series Randling, produced by Zapruder’s other films and the ABC © ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-171-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au randle. n. A nonsensical poem recited by Irish schoolboys as an apology for farting at a friend. Randling – created for ABC1 by Andrew Denton and Jon Casimir, the creators of The Gruen Transfer – is a game show about words. The game show pits ten teams, with two players a side, against each other over twenty-seven rounds of fiery and fierce word play. Each team is vying for a place in the 2012 Randling Grand Final and the chance to take home the Randling premiership trophy. Designed to enlighten, educate and amuse viewers, Randling is the only game show that comes with a guarantee that every episode will leave you at least 1 per cent smarter and 100 per cent happier. Learn more about Randling, the randlers and how to randle online at <http://www.abc.net.au/tv/randling/>. How to make an English lesson funner-er. One of the stated aims of The understanding and skills within the LEARNING OUTCOMES Australian Curriculum: English is to strand of Language and within this ensure that students appreciate, enjoy strand to examine the substrands Students learn that language is and use the English language in all its of: language variation and change; constantly evolving due to historical, variations and develop a sense of its language for interaction; expressing social and cultural changes, richness and power to evoke feelings, and developing ideas; and sound and demographic movements and technological innovations; convey information, form ideas, facili- letter knowledge. -

Whinger! Wowser! Wanker! Aussie English: Deprecatory Language and the Australian Ethos

Proceedings of the 2003 Conference of the Australian Linguistic Society 1 Whinger! Wowser! Wanker! Aussie English: Deprecatory language and the Australian ethos Karen Stollznow University of New England [email protected] 1. Introduction Abusive epithets form a significant part of the vocabulary of many people and have become a colourful and expressive part of the Australian lexicon, surfacing with great frequency within Australian television, radio, literature, magazines, newspapers and in domestic, social and work domains. Australian terms of abuse are unique compared to those found in other varieties of English. Geoffrey Hughes (1991:176) comments: “the Australian speech community has developed its distinctive array of insults and swear words”. The aim of this study is to examine the meaning, usage and cultural significance of the popular abusive epithets whinger, wowser and wanker as they are used in contemporary Australian English. Australians are often perceived as honest, forthright and upfront. Renwick (1980:22-29) observes: “Australian men and women are friendly, humorous and sardonic and can also be derisive, disdainful and scornful. They readily express negative feelings and opinions about both situations and people, sometimes about people they are with.” The words selected for this study are culturally significant and representative of social values in that they express characteristics deemed undesirable in Australian society. Abusive epithets are labels that admonish deviant social behaviour and can be considered to be keys to understanding synchronic cultural values. E.g. the socially leveling term wanker ridicules a person who is pretentious and arrogant, thereby suggesting that humility, solidarity and being down-to-earth are highly valued qualities in Australian society. -

A Note on Analysis and Circular Definitions

A Note on Analysis and Circular Definitions Francesco Orilia Department of Philosophy, University of Macerata (Italy) Achille C. Varzi Department of Philosophy, Columbia University, New York (USA) (Published in Grazer philosophische Studien 54 (1998), 107–115.) I An analysis—in its simplest form—is an assertion aiming to capture a cer- tain intimate link between a given concept (the analysandum) and another, typically more precise and fully explicit concept (the analysans). For in- stance, the following are classical examples of analyses proposed for the geometric concept of a circle and the epistemic concept of knowledge, re- spectively: (1) A circle is a locus of points in the same plane equidistant from some common point. (2) Knowledge is justified true belief. In some cases, even a whole theory may be regarded as a constituting an analysis. For example, Russell’s celebrated theory of definite descriptions may be viewed as an analysis of that formal concept which in natural lan- guage can be expressed by means of the definite article.1 Analyses are also called philosophical, real, or simply analyzing defi- nitions. This is appropriate, since analyses are implicitly assumed to fulfill the following Definition Constraint: (DC) An analysis must obey the laws governing definitions, where the expression standing for the analysans is viewed as a defi- niens and the expression standing for the analysandum as a corresponding definiendum. 2 1 Given the ordinary account of definitions, (DC) in turn implies the follow- ing Substitutivity Principle: (SP) The expression standing for the analysandum and the one standing for the analysans are mutually substitutable, salva veritate. -

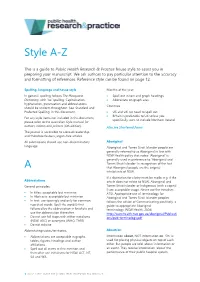

A to Z Style Guide

Style A-Z This is a guide to Public Health Research & Practice house style to assist you in preparing your manuscript. We ask authors to pay particular attention to the accuracy and formatting of references. Reference style can be found on page 12. Spelling, language and house style Months of the year: In general, spelling follows The Macquarie • Spell out in text and graph headings Dictionary, with ‘ise’ spelling. Capitalisation, • Abbreviate on graph axes. hyphenation, punctuation and abbreviations Countries: should be uniform throughout. See ‘Standard and Preferred Spelling’ in this document. • US and UK: no need to spell out • Britain is preferable to UK unless you For any style items not included in this document, specifically want to include Northern Ireland. please refer to the Australian Style manual for authors, editors and printers (6th edition). Also see Shortened forms The journal is accessible to a broad readership and therefore favours jargon-free articles. All submissions should use non-discriminatory Aboriginal language. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are generally referred to as Aboriginal in line with NSW Health policy that notes: ‘Aboriginal’ is generally used in preference to ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ in recognition of the fact A that Aboriginal people are the original inhabitants of NSW. If a distinction for clarity must be made, e.g. if the Abbreviations article does not relate to NSW, Aboriginal and General principles: Torres Strait Islander or Indigenous (with a capital I) are acceptable usage. Never use the initialism • In titles: acceptable but minimise ATSI. Appropriate use of terminology for • In Abstracts: acceptable but minimise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples • In text: use sparingly and only for common, follows the advice of Communicating positively: a repeated words. -

Dictionary of Lexicography

Dictionary of Lexicography Anyone who has ever handled a dictionary will have wondered how it was put together, where the information has come from, and how and why it can benefit so many of its users. The Dictionary of Lexicography addresses all these issues. The Dictionary of Lexicography examines both the theoretical and practical aspects of its subject, and how they are related. In the realm of dictionary research the authors highlight the history, criticism, typology, structures and use of dictionaries. They consider the subjects of data-collection and corpus technology, definition-writing and editing, presentation and publishing in relation to dictionary-making. English lexicography is the main focus of the work, but the wide range of lexicographical compilations in other cultures also features. The Dictionary gives a comprehensive overview of the current state of lexicography and all its possibilities in an interdisciplinary context. The representative literature has been included and an alphabetically arranged appendix lists all bibliographical references given in the more than 2,000 entries, which also provide examples of relevant dictionaries and other reference works. The authors have specialised in various aspects of the field and have contributed significantly to its astonishing development in recent years. Dr R.R.K.Hartmann is Director of the Dictionary Research Centre at the University of Exeter, and has founded the European Association for Lexicography and pioneered postgraduate training in the field. Dr Gregory James is Director of the Language Centre at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, where he has done research into what separates and unites European and Asian lexicography. -

Questions and Answers Dictionary Convenient Definitions of the Word

Questions And Answers Dictionary convenient definitions of the word. This question is not about LMGTFY questions and answers. It is only about whether Google Dictionary is a valid reference. SAP ABAP Data Dictionary Job Interview Questions with Answer for company placement. sappage.blogspot.com/ sap abap interview questions for experienced sap. I am attempting to save this dictionary to playerprefs: String, Dictionary._String The best place to ask and answer questions about development with Unity. Python Questions and Answers – Dictionary – 1. This set of Python Questions & Answers focuses on “Dictionaries”. 1. Which of the following statements create. A Yahoo Answer trolls is usually someone who enjoys to annoy everyone else on The Reporter Trolls: Reports innocent questions and answers that are not. Questions And Answers Dictionary Read/Download Definitionado Questions & Answers for iPhone - iPod - The longest word in the dictionary. To evaluate if an answer is correct you perform the following comparison: string.Equals( SelectedAnswer, question(RandomQuestion).Answer. This month we're talking to Erin McKean about her ideal dictionary Shop Talk The dictionary is seen as this arbiter of the One True Answer to any question. Which is the best offline dictionary for Ubuntu ? It should be Some Ubuntu Questions and Answers Installing English dictionary databeses (gcide, wn, devil): Recent questions and answers in Alien Dictionary. 0 votes. 1 answer 11 answered 2 days ago in Alien Dictionary by StefanPochmann (98,070 points). 0 votes. BusinessDictionary.com. BusinessDictionary Community one language to another? 0 answer. 1. judyfaggard asked on Aug 15, 2015. On a personal financial. I need to write a function get_value(dictionary, key) which returns the value of Top questions and answers, Important announcements, Unanswered questions. -

Abstract Introduction

Stephen Keith McGrath, Stephen Jonathan Whitty, (2018)," Accountability and responsibility defined", International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 11 Issue 3, pp.687-707, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-06-2017-0058 __________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract Purpose – To remove confusion surrounding the terms responsibility and accountability from the general and project management arenas by creating ‘refined’ (with unnecessary elements removed) definitions of these terms. Design/methodology/approach – A method of deriving refined definitions for a group of terms by ensuring there is no internal conflict or overlap is adopted and applied to resolve the confusion. Findings – The confusion between responsibility and accountability can be characterised as a failure to separate the obligation to satisfactorily perform a task (responsibility) from the liability to ensure that it is satisfactorily done (accountability). Furthermore, clarity of application can be achieved if legislative and organisational accountabilities are differentiated and it is recognised that accountability and responsibility transition across organisational levels. A difficulty in applying accountability in RACI tables is also resolved. Research limitations/implications – Clear definition of responsibility and accountability will facilitate future research endeavours by removing confusion surrounding the terms. Verification of the method used through its success in deriving these ‘refined’ definitions suggests its suitability for application to other contested terms. Practical implications – Projects and businesses alike can benefit from removal of confusion around the definitions of responsibility and accountability in the academic research they fund and attempt to apply. They can also achieve improvements in both efficiency and effectiveness in undertaking organisation-wide exercises to determine organisational responsibilities and accountabilities as well as in the application of governance models.