State-Corporate-Military Power and Post-Photographic Interventions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas J. Wright Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Thomas J. Wright 电影 串行 (大全) Blind Date https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/blind-date-3076846/actors Epiphany https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/epiphany-7885312/actors A Room With No View https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-room-with-no-view-4659273/actors In Arcadia Ego https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/in-arcadia-ego-19969055/actors Lily Sunder Has Some Regrets https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/lily-sunder-has-some-regrets-28149529/actors Baby https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/baby-25219029/actors Mamma Mia https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mamma-mia-27877368/actors All in the Family https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/all-in-the-family-25218480/actors Reichenbach https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/reichenbach-25218814/actors Backwash https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/backwash-4839830/actors Collateral Damage https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/collateral-damage-25217111/actors No Holds Barred https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/no-holds-barred-1194108/actors 10-8: Officers on Duty https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/10-8%3A-officers-on-duty-163851/actors ...Thirteen Years Later https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/...thirteen-years-later-16745526/actors Shell Shock (Part II) https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shell-shock-%28part-ii%29-16745684/actors Squall https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/squall-16746059/actors Oil & Water https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/oil-%26-water-16746300/actors Roosters https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/roosters-18153627/actors -

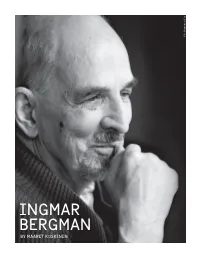

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Blood Meridian Or the Evening Redness in the West Dianne C

European journal of American studies 12-3 | 2017 Special Issue of the European Journal of American Studies: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12252 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12252 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference European journal of American studies, 12-3 | 2017, “Special Issue of the European Journal of American Studies: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds” [Online], Online since 27 November 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12252; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas. 12252 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. European Journal of American studies 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Cormac McCarthy Between Worlds James Dorson, Julius Greve and Markus Wierschem Landscapes as Narrative Commentary in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian or the Evening Redness in the West Dianne C. Luce The Novel in the Epoch of Social Systems: Or, “Maps of the World in Its Becoming” Mark Seltzer Christ-Haunted: Theology on The Road Christina Bieber Lake On Being Between: Apocalypse, Adaptation, McCarthy Stacey Peebles The Tennis Shoe Army and Leviathan: Relics and Specters of Big Government in The Road Robert Pirro Rugged Resonances: From Music in McCarthy to McCarthian Music Julius Greve and Markus Wierschem Cormac McCarthy and the Genre Turn in Contemporary Literary Fiction James Dorson The Dialectics of Mobility: Capitalism and Apocalypse in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road Simon Schleusener Affect and Gender -

TRANS 20 (2016) DOSSIER: INDIGENOUS MUSICAL PRACTICES and POLITICS in LATIN AMERICA Dancing in the Fields: Imagined Landscapes A

TRANS 20 (2016) DOSSIER: INDIGENOUS MUSICAL PRACTICES AND POLITICS IN LATIN AMERICA Dancing in the Fields: Imagined Landscapes and Virtual Locality in Indigenous Andean Music Videos Henry Stobart (Royal Holloway, University of London) Resumen Abstract El paso del casete de audio analógico al VCD (Video Compact Disc) The move from analogue audio cassette to digital VCD (Video Compact digital como soporte principal para la música gravada alrededor del Disc) in around 2003, as a primary format for recorded music, opened año 2003, abrió una nueva era para la producción y el consumo de up a new era for music production and consumption in the Bolivian música en la región de los Andes bolivianos. Esta tecnología digital Andes. This cheap digital technology both created new regional markets barata creó nuevos mercados regionales para los pueblos indígenas among low-income indigenous people, quickly making it almost de bajos ingresos, haciendo impensable para los artistas regionales unthinkable for regional artists to produce a commercial music producir una grabación comercial sin imágenes de vídeo desde recording without video images. This paper explores the character of entonces. Este artículo explora el carácter de estas imágenes, these images, reflecting in particular on the tendency to depict considerando en particular la tendencia a representar a los músicos musicians and dancers performing in rural landscapes. It charts a long y bailarines actuando en paisajes rurales. Traza la larga asociación association between Andean music and landscape, both in the global histórica entre la música andina y el paisaje, tanto en la imagination and in local practices, relating this to the idea of an Andean imaginación global como en las prácticas locales, relacionándola arcadia; a concept rooted in European classical imaginaries. -

Tricks of the Light

Tricks of the Light: A Study of the Cinematographic Style of the Émigré Cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan Submitted by Tomas Rhys Williams to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film In October 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to explore the overlooked technical role of cinematography, by discussing its artistic effects. I intend to examine the career of a single cinematographer, in order to demonstrate whether a dinstinctive cinematographic style may be defined. The task of this thesis is therefore to define that cinematographer’s style and trace its development across the course of a career. The subject that I shall employ in order to achieve this is the émigré cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, who is perhaps most famous for his invention ‘The Schüfftan Process’ in the 1920s, but who subsequently had a 40 year career acting as a cinematographer. During this time Schüfftan worked throughout Europe and America, shooting films that included Menschen am Sonntag (Robert Siodmak et al, 1929), Le Quai des brumes (Marcel Carné, 1938), Hitler’s Madman (Douglas Sirk, 1942), Les Yeux sans visage (Georges Franju, 1959) and The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961). -

100 Anni Di Ingmar Bergman

100 ANNI DI INGMAR BERGMAN settembre - dicembre 2018 UFFICIO CINEMA Collana a cura dell’Ufficio Cinema del Comune di Reggio Emilia piazza Casotti 1/c - 42121 Reggio Emilia telefono 0522/456632 - 456763 fax 0522/585241 cura rassegna e organizzazione 100 ANNI DI INGMAR BERGMAN Sandra Campanini cura catalogo Angela Cervi impaginazione Angela Cervi amministrazione Cinzia Biagi servizi tecnici Ero Incerti servizi diversi Giorgio Guerri Cinema Rosebud settembre - dicembre 2018 PROGRAMMA SOMMARIO lunedì 17 settembre 7 CIÒ CHE RISPONDE INGMAR BERGMAN, QUANDO RISPONDE • IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE (1957) 91’ 9 INTRODUZIONE di Jacques Mandelbaum lunedì 24 settembre 15 LO SCHIAFFO DI “LUCI D’INVERNO” • MONICA E IL DESIDERIO (1952) 92’ di Aldo Garzia mercoledì 7 novembre 21 I COLLEGHI REGISTI, LA CURIOSITÀ PER I GIOVANI di Aldo Garzia • IL SETTIMO SIGILLO (1957) 96’ LE SCHEDE lunedì 26 novembre 31 IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE • SUSSURRI E GRIDA (1972) 91’ 41 MONICA E IL DESIDERIO lunedì 10 dicembre 51 IL SETTIMO SIGILLO • SCENE DA UN MATRIMONIO (1975) 168’ 61 SUSSURRI E GRIDA 71 SCENE DA UN MATRIMONIO mercoledì 19 dicembre 79 FANNY E ALEXANDER • FANNY E ALEXANDER (1982) 188’ 93 BIOGRAFIA 101 FILMOGRAFIA 4 5 “”CIÒ CHE RISPONDE INGMAR BERGMAN, QUANDO RISPONDE” (Il regista)... È un illusionista. Se guardiamo l’elemento fondamentale dell’arte cinematografica constatiamo che questa si compone di piccole immagini rettangolari ognuna delle quali è separata dalle altre da una grossa riga nera. Guardando più da vicino si scopre che questi minuscoli rettangoli, i quali a prima vista sembrano contenere lo stesso motivo, differiscono l’uno dall’altro per una modificazione quasi impercettibile di tale motivo. -

Index, BYU Studies

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 43 Issue 4 Article 14 10-1-2004 Index, BYU Studies BYU Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Studies, BYU (2004) "Index, BYU Studies," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 43 : Iss. 4 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol43/iss4/14 This Index is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Studies: Index, BYU Studies X BYU Studies, Volume 43 These indexes will be added to our cumulative indexes, available on our ;i: website at http://byustudies.byu.edu. Authors Allen, James B., review of An Insider's View of Mormon Origins, by Grant H. Palmer, 43:2:175-89. Barsch, Wulf, "To Depict Infinity: The Artwork of Wulf Barsch," 43:4:33-38. Bessey, Kent A., "To Journey Beyond Infinity," 43:4:23-32. Brady, Jane D., "Falling Leaves," 43:4:137-39. Burton, Gideon O., "Mormons, Opera, and Mozart," 43:3:23-29. Chadwick, Bruce A. See McClendon, Richard J. Crandall, David P., "Monostatos, the Moor," 43:3:170-79. Cutler, Edward S., review of By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scrip ture That Launched a World Religion, by Terryl L. Givens, 43:4:150-56. Dalton, Aaron, "Diese Aufnahme ist bezaubernd schon: Deutsche Grammo- phon's 1964 Recording of The Magic Flute," 43:3:251-69. Duncan, Dean, "Adaptation, Enactment, and Ingmar Bergman's Magic Flute," 43:3:229-50. -

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918. -

·ļ¯Æ ¼Æ›¼ Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

è‹±æ ¼çŽ›Â·ä¼¯æ ¼æ›¼ 电影 串行 (大全) Ingmar Bergman's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ingmar-bergman%27s-cinema-59725709/actors Cinema Herr Sleeman kommer https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/herr-sleeman-kommer-28153912/actors FÃ¥rö trilogy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-trilogy-12043076/actors Crisis https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/crisis-1066211/actors The Blessed Ones https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-blessed-ones-1079728/actors Port of Call https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/port-of-call-1108471/actors Thirst https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/thirst-1188701/actors FÃ¥rö Document 1979 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-document-1979-18239069/actors Stimulantia https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stimulantia-222633/actors The Venetian https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-venetian-2276647/actors The Image Makers https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-image-makers-2755257/actors Don Juan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/don-juan-3035815/actors FÃ¥rö Document https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/f%C3%A5r%C3%B6-document-64768851/actors metaphysical trilogy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/metaphysical-trilogy-98970250/actors 女人的秘密 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E5%A5%B3%E4%BA%BA%E7%9A%84%E7%A7%98%E5%AF%86-1078811/actors é¢ å” https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E9%9D%A2%E5%AD%94-1078890/actors 愛的一課 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E6%84%9B%E7%9A%84%E4%B8%80%E8%AA%B2-1091180/actors -

Lisa Barnard 32 Smiths Square Photographic Commission

8 Paddock Road Lisa Barnard Lewes East Sussex BN7 1UU 32 Smiths Square Mob: 07796 374 237 Photographic Commission Web: lisabarnard.co.uk MAGGIE 7 OF 8 32 Smiths Square The old conservative party headquarters at 32 Smiths Square is synonymous with Margaret Thatcher smiling and waving gleefully out of the window on the 2nd floor, after winning the elections of 1979/83/87. The building was the home of the Conservative party from1958 to 2003 and thus represents an important period within our political history. It is common knowledge that Thatcher took a vehement stand against persistently contested European integration and hence the photographic representation of the space will perhaps suggest a degree of satire –the building will re-open as ‘Europe House’ in October 2010. The symbolism of the dulled shades of blue, peeling paintwork and iconography of past alliances will inevitably draw comparisons between the previous use of the building and the hope and importance of the buildings future inhabitants. The building had a notorious reputation for being partly responsible for the demise of the conservative party with its ‘rabbit warren’ style layout, encouraging descent and backstabbing. It is well documented that Michael Howard, during his brief time as leader, made it a priority to move the Conservative Central Office to an environment more ‘aesthetically pleasing’. Lord Parkinson –chairman of the Conservative Party from 1981 to 1983 and again from 1997 to 1998-, said: “a distinctly shabby feel at Central Office was encouraged by the then-treasurer Lord McAlpine, to create a parsimonious air to encourage donors to be generous. -

Millennium – Opening Episode Quotations and Proverbs

MillenniuM – Opening Episode Quotations and Proverbs Pilot Season: 1 MLM Code: 100 Production Code: 4C79 Quotation: None Gehenna Season: 1 MLM Code: 101 Production Code: 4C01 Quotation: I smell blood and an era of prominent madmen - W.H. Auden Dead Letters Season: 1 MLM Code: 102 Production Code: 4C02 Quotation: For the thing I greatly feared has come upon me. And what I dreaded has happened to me, I am not at ease, nor am I quiet; I have no rest, for trouble comes. - Job 3:25,26 Kingdom Come Season: 1 MLM Code: 103 Production Code: 4C03 Quotation: And there will be such intense darkness, That one can feel it. - Exodus 10:21 The Judge Season: 1 MLM Code: 104 Production Code: 4C04 Quotation: ...the visible world seems formed in love, the invisible spheres were formed in fright. - H. Melville 1819-1891 522666 Season: 1 MLM Code: 105 Production Code: 4C05 Quotation: I am responsible for everything... except my very responsibility. - Jean-Paul Sartre ©2006 http://Millennium-ThisIsWhoWeAre.net Blood Relatives Season: 1 MLM Code: 106 Production Code: 4C06 Quotation: This generation is a wicked generation; it seeks for a sign, and yet no sign shall be given to it... - Luke 11:29 The Well-Worn Lock Season: 1 MLM Code: 107 Production Code: 4C07 Quotation: The cruelest lies are often told in silence. - Robert Louis Stevenson Wide Open Season: 1 MLM Code: 108 Production Code: 4C08 Quotation: His children are far from safety; They shall be crushed at the gate Without a rescuer. - Job 5:4 Weeds Season: 1 MLM Code: 109 Production Code: 4C09 Quotation: But know ye for certain..