Lisa Barnard 32 Smiths Square Photographic Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bpb Guide Vaw.Indd

Festival Magazine Sponsors EVENTS Thursday 2 October 5pm–6pm ETHICS AND THE PUBLIC USE OF FILM PROGRAMME EDUCATION EVENTS Looking at or making images of war and pain Julian Stallabrass IMAGES OF WAR: A DEBATE raises important questions about how we view Julian Stallabrass (BPB 2008 Guest Duke of York’s Picturehouse, POST UP: THE WAR OF IMAGES human suffering. This event, with contributions BPB 2008 CONFERENCE Curator) explores the festival themes in Fabrica 40 Duke Street, Brighton, bn1 1ag Preston Circus, Brighton from University of Brighton students, explores MEMORY OF FIRE: THE WAR OF conversation with Helen Cadwallader Wednesday 12 November Sunday 26 October Jubilee Square, Brighton: (Project Hub at some of these issues. Suitable for those studying IMAGES AND IMAGES OF WAR (BPB Executive Director). Julian Stallabrass 6pm–8pm Matinee – please check with cinema for Lighthouse, 28 Kensington Street, Brighton) Media, Politics, Humanities, Photography, 15.10.09 lectures in modern and contemporary To book: contact [email protected] or 01273 778646 exact screening time and ticket prices Friday 14 November and Saturday 15 November Philosophy, History, Religious Studies or Art. art at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Admission: free T:0871 7042056 10am–4pm Sallis Benney Theatre A collaboration with the Mass Observation Archive An event for FE students. Presented in partnership University of Brighton, Grand Parade Friday 3 October 5pm–6pm Do we NEED to see what war does to people? Ought Standard Operating Procedure (cert 15) with the University of Brighton. Saturday 15 November Ashley Gilbertson we HAVE TO see it? When does shock give way to Director: Errol Morris. -

Mark-Power-CV.Pdf

MARK POWER / CURRICULUM VITAE PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE 2007 - present Member of Magnum Photos 2004 - present Professor of Photography, University of Brighton 2005 - 2007 Associate of Magnum Photos 2002 - 2005 Nominee of Magnum Photos 1992 - 2004 Senior Lecturer in Photography, University of Brighton 1988 – 2002 Member of Network Photographers EDUCATION 1977 – 1978 Loughborough College of Art: Foundation ! 1978 - 1981 Brighton Polytechnic: BA Hons Visual Communication (1st Class) MONOGRAPHS 2014 DIE MAUER IST WEG! (Globtik Books/Self-Published) ISBN 978-0-9930830-0-6 2013 MASS (Gost) ISBN 978-0-9574272-1-1 2012 MARK POWER’S BLACK COUNTRY STORIES (magazine) (Multistory) 2010 THE SOUND OF TWO SONGS (Photoworks) ISBN 978-1-903796-39-9 2010 DESTROYING THE LABORATORY FOR THE SAKE OF THE EXPERIMENT (Self-published, with Daniel Cockrill) 2008 SIGNES (Gulbenkian exhibition catalogue) ISBN 978-972-8462-46-8 2007 26 DIFFERENT ENDINGS (Photoworks) ISBN 1-903796-21-0 2002 THE TREASURY PROJECT (Photoworks) ISBN 1-903796-05-9 2000 SUPERSTRUCTURE (Harper Collins Illustrated) ISBN 0-00-220205-0 1996 THE SHIPPING FORECAST (Zelda Cheatle Press/Network)! (2nd printing 1997 / 3rd printing 1998) ISBN 1-899823-02-6 1988 WESTMINSTER CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL (Photographers Gallery catalogue) SOLO EXHIBITIONS (selected) 2014 – 2015 THE CITY OF SIX TOWNS Hanley City Centre, Stoke-on-Trent (outdoor exhibition) 2014 OPEN FOR BUSINESS – BOMBARDIER and NISSAN National Railway Museum, York, UK 2012 MARK POWER’S BLACK COUNTRY STORIES The New Art Gallery, Walsall, UK 2010 - 2012 -

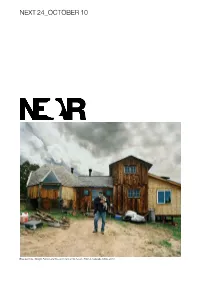

Next24 October10

NEXT 24_OCTOBER 10 Élisa Larvego, George Parrish and his cat in front of his house, Triple A, Colorado (USA), 2010 NEXT 24_OCTOBER 10_P3 SOMMAIRE / CONTENTS Élisa Larvego, Huerfano Valley's view from Jim Fowler's house, Libre, Colorado (USA), 2010 NEAR • association suisse pour la photographie contemporaine • avenue vinet 5 • 1004 lausanne • www.near.li • [email protected] NEXT 24_OCTOBER 10_P4 SOMMAIRE / CONTENTS Élisa Larvego, Mary Ann's actual oat house, Libre, Colorado (USA), 2010 RUBRIQUES NEAR P7 INTERVIEW P19 EVENEMENTS / EVENTS P35 EXPOSITIONS / EXHIBITIONS P49 FESTIVALS P143 PUBLICATIONS P163 PRIX / AWARDS P177 FORMATION / EDUCATION P191 EDITO DE NEXT C'est avec grand plaisir que nous présentons dans NEXT24 une interview de la photographe Anne Golaz qui s'entretient avec Emmanuelle Bayart à propos de sa nouvelle série, Chasses, et un portfolio d'images récentes d'Elisa Larvego consacré à deux communautés hippies du Colorado. Les photographes de NEAR sont également présents dans les festivals et de nombreuses expositions en Suisse comme ailleurs… Cet automne offre plusieurs occasions de participer à des prix, concours ou appels à la création de festivals, profitez-en ! ! ! Excellente lecture ! Nassim Ont contribué à ce numéro : Interview : Emmanuelle Bayart ; Maquette : Ilaria Albisetti, www.latitude66.net ; Rédaction : Nassim Daghighian, présidente de NEAR Pour recevoir NEXT ou pour nous informer de vos activités liés à la photographie (en) Suisse, prière de nous contacter par e-mail : [email protected] NEAR • association suisse pour la photographie contemporaine • avenue vinet 5 • 1004 lausanne • www.near.li • [email protected] NEXT 24_OCTOBER 10_P5 PORTFOLIO Élisa Larvego, Mary Ann Flood in her house, Libre, Colorado (USA), 2010 PORTFOLIO Elisa Larvego www.vego.ch Communautés de Huerfano Valley, Triple A et Libre " De toute évidence, dans mes portraits, les lieux sont souvent aussi importants que les personnes photographiées. -

How Margaret Thatcher's HQ Turned Into Chateau Despair by Sean O

3/14/13 How Margaret Thatcher's HQ turned into Chateau Despair | Art and design | guardian.co.uk Welcome Lisa Barnard, sign into the Guardian with Facebook How Margaret Thatcher's HQ turned into Chateau Despair Lisa Barnard's photographs of the drab former Tory party headquarters show the fleeting nature of political power – with Thatcher's image left to get damp and discoloured in a cupboard Sean O'Hagan guardian.co.uk, Thursday 28 February 2013 17.24 GMT Empty smiles … mouldy photographs of Iain Duncan Smith at 32 Smith Square Eight identikit portraits of Margaret Thatcher, steelyeyed, almost smiling, punctuate www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/feb/28/chateau-despair-photography-margaret-thatcher 1/5 3/14/13 How Margaret Thatcher's HQ turned into Chateau Despair | Art and design | guardian.co.uk the pages of Chateau Despair. Each one is blemished to a different degree by creeping mould, which has vividly discoloured the lower edges of the paper. The old photographs were uncovered in a damp, disused cupboard in 32 Smith Square, Westminster, which was the head office of the Conservative party from 1958 to 2004. They provide a distinctly Warholian undertow to the main body of work in Lisa Barnard's new book, a psychic investigation of this empty, neglected space where political power used to reside – and where a freemarket ideology was created that continues to shape our lives. Chateau Despair Chateau Despair is one of three books that launch the new by Lisa Barnard independent imprint Gost Books. Its pointed title may or may not reflect Barnard's view of Thatcher's reign and, by extension, the Britain the socalled Iron Lady made in her own image. -

State-Corporate-Military Power and Post-Photographic Interventions

Strategies of Visualisation: State-Corporate-Military Power and Post-Photographic Interventions Nicolette Barsdorf-Liebchen, BA(Hons), MA PhD in Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies Cardiff University May 2018 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgments Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Overview and Aims of the Enquiry 3 1.1 Time Frame 5 1.2 Selection of Image-makers 6 2 Questions and Objectives, Contexts and Literatures 11 2.1 Making Distinctions: Visual Studies, Visual Culture, Critical Visuality 14 2.2 Note on Methodology 18 3. Critical Review of Literatures, Debates and Concepts 27 3.1 Historical Background 39 3.2 Grasping the Socially Abstract: Visualising the Post-photographic 47 3.3 Traditional vs Social Media? 48 4. Key Concepts 49 4.1 "War": a Fare of Mediality, Media Ecology and Mediatization 49 4.2 Plexus: on the Search for a Term 54 4.3 Corporate Personhood and the Corporate Veil 60 4.4 Visualisation and Ostension 67 4.5 The Post-photographic 69 5. Chapter Outlines 75 Chapter One: Complicity, Secondary Witnessing and the Journey from Atrocity to Facelessness 1.1 Introduction 82 1.2 Themes and Structure 86 1.3 Note on Extant Literature, Frameworks and Debates 89 1.4 Complicity in historical context: “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” 90 1.5 Secondary Witnessing and "Gegenwärtige Bewältigung" 94 1.6 The Watchful Gaze and Complicity as Biblical Trope 95 1.7 Whither Complicity for the Post-photographic? 99 1.8 In Conclusion 104 Chapter Two: The (an)Iconic Challenge and Post-photographic Discontents 2.1 Introduction: Aims, Themes and Questions 107 -

Book XII Photographers

V VV VV V VVVVon.com VVVV Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XII - Photographers Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Photographer ............................................. 1 1.1.1 Duties and functions ..................................... 1 1.1.2 Selling photographs ..................................... 3 1.1.3 Photo sharing ......................................... 5 1.1.4 References .......................................... 5 1.1.5 External links ......................................... 5 1.2 Truth claim (photography) ....................................... 5 1.2.1 Indexicality .......................................... 5 1.2.2 Visual accuracy ........................................ 5 1.2.3 Consequences of the “truth claim” .............................. 6 1.2.4 Digital photography ...................................... 6 1.2.5 Criticism of the “truth claim” ................................. 7 1.2.6 References .......................................... 7 2 Day 2 9 2.1 List of photographers ......................................... 9 2.1.1 Albania ............................................ 10 2.1.2 Argentina ........................................... 10 2.1.3 Australia ........................................... 10 2.1.4 Austria ............................................ 11 2.1.5 Azerbaijan .......................................... 11 2.1.6 Bangladesh .......................................... 12 2.1.7 Belgium ............................................ 12 2.1.8 Benin ............................................ -

Press Release BRIGHTON PHOTO FRINGE 2

Press Release BRIGHTON PHOTO FRINGE 2 Oct – 14 Nov 2010 Various locations Brighton Photo Fringe is a vibrant event that engages with photographers, lens-based artists and a diverse public audience. Every two years Brighton Photo Fringe coordinates a city-wide festival of exhibitions and events in partnership with Brighton Photo Biennial. This October Brighton Photo Fringe returns with its largest festival to date. Continuing to grow and expand, this year’s festival includes over 130 exhibitions, projects and events, spreading as far as Hastings and Chichester. New for 2010 are major national and international projects, including groups from Belfast, Liverpool and Africa. Integral to Brighton Photo Fringe is a programme of events, workshops and activities that create opportunities for everyone to participate. Appearing in every corner of the city and beyond, highlights include: NOTHING IS IN THE PLACE AVI, Anonymous (Value Action), Donald Christie, Vicki Churchill, Brett Dee, Nigel Dickinson, Chris Dyer, Jason Evans, Anna Fox, Ken Grant, Nick Knight, Mark Lally, Clive Landen, Gordon MacDonald, Martin Parr, Vinca Petersen, Mark Power, Paul Reas, Richard Sawdon-Smith, Helen Sear, Paul Seawright, Nigel Shafran, Wolfgang Tillmans, Nick Waplington, Jack Webb, Tom Wood, Dan Wootton. A curatorial project by Jason Evans. 2 Oct – 14 Nov Fringe Focus, The Old Co-op Building, 94-101 London Rd, Brighton, BN1 4LB Nothing is in the Place is a subjective survey that remembers life in 1990’s Britain. The show is an introduction to some of the photography that was made at that time offering glimpses of political unrest, social upheaval and analogue youth culture. -

Newsletter 17.Indd

CRD Centre for Research Development UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON researchnewsFACULTY OF ARTS AND ARCHITECTURE Performance and Visual Art Students International Success How We Are: Folk Pottery Photographing Museum Britain Northeast Georgia At the Tate 23 2 CRD Centre for Research Development UNIVERSITY OF BRIGHTON ����������������������������������� ����������������������� �������������������������������������������� Performance and Visual Art The Research Students researchnews International Success Collective for Dress Spring 2007/Edition 17 History and Fashion How We Are Performance and Visual Studies Research Photographing Britain 2 Art students: International Collective visit Paris 20 How We Are: Folk Pottery Photographing Museum Britain Northeast Georgia At the Tate 23 Studies Successes 8 2 The Research Collective Researching new dye for Dress History and The Spring Group: colours: in the mid- COVER IMAGE: The Research Collective for Dress History and Fashion Studies has been Fashion Studies 3 Research Activities nineteenth century 22 A German Grandchild’s Funeral directed by Silke Mansholt. recently formed at the University of Brighton, based in the School of January - April 2007 10 Historical and Critical Studies. This has been formed in order to enable, Kill House: An Folk Pottery Museum: Photograph by Billy Cowie. enhance and publicise collective research and debate in the fields of architecture of fear 4 Historiographic practice Northeast Georgia 23 Performance and Visual Art and a whiff of sulphur! 12 Students: International Success. dress history and fashion studies amongst those in the University of Include 2007: Conference Chain: at the Chinese Art Full story on page 8. Brighton and its surrounding communities who have an interest in, or on Inclusive Design 5 Staff News 16 Centre, Manchester 23 are undertaking study in these and related fields.