Theory and Practice of Self-Translation in the Basque Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 6 The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre Their History and Their Traditions by Philippe Veyrin Translated by Andrew Brown Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 6 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2011 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2011 by Jose Luis Agote Cover illustration: Xiberoko maskaradak (Maskaradak of Zuberoa), drawing by Paul-Adolph Kaufman, 1906 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veyrin, Philippe, 1900-1962. [Basques de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre. English] The Basques of Lapurdi, Zuberoa, and Lower Navarre : their history and their traditions / by Philippe Veyrin ; with an introduction by Sandra Ott ; translated by Andrew Brown. p. cm. Translation of: Les Basques, de Labourd, de Soule et de Basse Navarre Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic book on the Basques of Iparralde (French Basque Country) originally published in 1942, treating Basque history and culture in the region”--Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-877802-99-7 (hardcover) 1. Pays Basque (France)--Description and travel. 2. Pays Basque (France)-- History. I. Title. DC611.B313V513 2011 944’.716--dc22 2011001810 Contents List of Illustrations..................................................... vii Note on Basque Orthography......................................... -

Basque Studies

Center for BasqueISSN: Studies 1537-2464 Newsletter Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R Basque Literature Series launched at Frankfurt Book Fair FALL Reported by Mari Jose Olaziregi director of Literature across Frontiers, an 2004 organization that promotes literature written An Anthology of Basque Short Stories, the in minority languages in Europe. first publication in the Basque Literature Series published by the Center for NUMBER 70 Basque Studies, was presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair October 19–23. The Basque Editors’ Association / Euskal Editoreen Elkartea invited the In this issue: book’s compiler, Mari Jose Olaziregi, and two contributors, Iban Zaldua and Lourdes Oñederra, to launch the Basque Literature Series 1 book in Frankfurt. The Basque Government’s Minister of Culture, Boise Basques 2 Miren Azkarate, was also present to Kepa Junkera at UNR 3 give an introductory talk, followed by Olatz Osa of the Basque Editors’ Jauregui Archive 4 Association, who praised the project. Kirmen Uribe performs Euskal Telebista (Basque Television) 5 was present to record the event and Highlights 6 interview the participants for their evening news program. (from left) Lourdes Oñederra, Iban Zaldua, and Basque Country Tour 7 Mari Jose Olaziregi at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Research awards 9 Prof. Olaziregi explained to the [photo courtesy of I. Zaldua] group that the aim of the series, Ikasi 2005 10 consisting of literary works translated The following day the group attended the Studies Abroad in directly from Basque to English, is “to Fair, where Ms. Olaziregi met with editors promote Basque literature abroad and to and distributors to present the anthology and the Basque Country 11 cross linguistic and cultural borders in order discuss the series. -

Canonical and Non-Canonical Narrative in the Basque Context

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hedatuz Canonical and non-canonical narrative in the basque context Olaziregi Alustiza, María José Euskal Herriko Unib. Filologia, Geografia eta Historia Fak. Unibertsitateko ibilbidea, 5. 01006 Vitoria-Gateiz [email protected] BIBLID [0212-7016 (2001), 46: 1; 325-336] Artikulu honetan euskal narratibaren egungo egoeraz egiten da hausnarketa. XX. mendean sendotuz joan den generoa dugu narratibazkoa eta gaur egungo euskarazko literatur produkzioan protagonismo erabatekoa du. Horretaz hitz egiten da artikuluan, narratibaren bilakaeraz eta egungo egoeraz. Guztiaren osagarri, euskal literatur sistema, euskal literaturak Espainian nahiz atzerrian duen proiekzio eskasa eta azken urteotako eleberriaren joera nagusiak aztertzen dira. Giltza-Hitzak: Literatur kritika. Literaturaren Historia. Euskal Literatura. Literatura Konparatua. En el presente artículo se reflexiona sobre la situación actual de la literatura vasca. La narrativa es un género que ha ido fortaleciéndose durante el siglo XX y que hoy en día detenta el protagonismo absoluto en la producción de la literatura en lengua vasca. De todo ello se habla en este artículo, de la evolución de la narrativa y de su situación actual. Para completar el trabajo se estudian la escasa proyección que en España y en en el extranjero tiene el sistema de literatura vasca, la literatura vasca, y las principales tendencias de la novela en estos últimos años. Palabras Clave: Crítica Literaria. Historia de la Literatura. Literatura Vasca. Literatura Comparada. Dans cet article, on examine la situation actuelle de la littérature basque. Le roman est un genre qui s’est affirmé durant le XXe siècle et qui détient aujourd’hui la primeur absolue dans la production de la littérature en langue basque. -

Procès-Verbal De La Séance Du Conseil Municipal Du Vendredi 20 Juillet 2012 À 18H00

Procès-verbal de la séance du Conseil municipal du vendredi 20 juillet 2012 à 18h00 M. le Maire Nous désignons un secrétaire de séance en la personne de M. André Larrasoain qui va procéder à l’appel. Le quorum étant atteint, nous procédons à l’approbation du procès-verbal de la séance du Conseil municipal du 1er juin 2012. Adopté à l’unanimité ________________________ N° 1 - FINANCES BUDGET GENERAL : DECISION MODIFICATIVE N° 2 M. le Maire expose : Dans le cadre de l’exécution budgétaire 2012, il convient de prévoir une décision modificative n° 2 afin d’ajuster certaines lignes comptables de la section d’investissement. En section d’investissement • Une nouvelle opération de constructions de 36 logements locatifs sociaux sur le programme «Itsas Larrun» a été lancée et donne lieu à versement d’une participation de la commune à hauteur de 3 % du prix total soit 99.823,60 € (versement de 50 % au démarrage des travaux en 2012 et 50 % à la livraison des logements en 2013). La CCSPB verse une participation financière de 20 % de cette subvention sur l’opération (soit 19.964,72 €). Ainsi, sur l’exercice 2012, la commune versera une subvention de 49.911,80 € au démarrage des travaux, et percevra en recettes la somme de 9.982,35 € de la CCSPB (cf annexe). • L’opération d’aménagement du carrefour giratoire Erromardie (Pavillon Bleu), réalisée sous co-maîtrise d’ouvrage avec le Conseil général des Pyrénées-Atlantiques, initialement prévue en 2013, peut débuter dès 2012. 2 Son lancement nécessite l’ouverture d’une AP/CP avec des crédits sur le budget primitif 2012 d’un montant de 100.000 €. -

Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: a 21St Century Perspective

MULTILINGUAL MATTERS 116 Series Editor: John Edwards Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective Edited by Joshua A. Fishman MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Can Threatened Languages Be Saved? Reversing Language Shift Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective/Edited by Joshua A. Fishman. Multilingual Matters: 116 Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Language attrition. I. Fishman, Joshua A. II. Multilingual Matters (Series): 116 P40.5.L28 C36 2000 306.4’4–dc21 00-024283 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1-85359-493-8 (hbk) ISBN 1-85359-492-X (pbk) Multilingual Matters Ltd UK: Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon BS21 7HH. USA: UTP, 2250 Military Road, Tonawanda, NY 14150, USA. Canada: UTP, 5201 Dufferin Street, North York, Ontario M3H 5T8, Canada. Australia: P.O. Box 586, Artarmon, NSW, Australia. Copyright © 2001 Joshua A. Fishman and the authors of individual chapters. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Index compiled by Meg Davies (Society of Indexers). Typeset by Archetype-IT Ltd (http://www.archetype-it.com). Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd. In memory of Charles A. Ferguson 1921–1998 thanks to whom sociolinguistics became both an intellectual and a moral quest Contents Contributors . vii Preface . xii 1 Why is it so Hard to Save a Threatened Language? J.A. -

Basque Studies Newsletter ISSN: 1537-2464 Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for Basque Studies Newsletter ISSN: 1537-2464 Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R An Interview with 2009-2010 Douglass Scholar Santiago de Pablo Fall Vitoria, October 6, 2010. University of the Basque Country 2010 By Oscar Álvarez Gila. Oscar: Let’s start by getting to know you. NUMBER 78 photo: L. Corcostegui Could you give us a brief summary of your life experience and your career as a In this issue: historian? (Earth Without Peace. Civil War, Film and Propaganda in the Basque Country, Madrid, Santi: I was born in 1959 in Tabuenca, Biblioteca Nueva, 2006) in which I explore Santi de Pablo Interview 1 a small town in Aragon, near southern the use of film for the dissemination of propaganda during the Civil War in Euskadi. Oscar Álvarez 3 Navarra, where my father worked as a doctor. When I was seven years old my I have also organized an annual conference, Co-Directors’ Message 3 family moved to Vitoria-Gasteiz and, except History through Cinema, since 1998 in Vitoria, and I am a member of the Academy of Publications Coordinator for three years in which I studied at the 4 University of Navarra, my career has always Motion Picture Arts and Sciences of Spain. Lehendakari Visit 4 been linked to the capital of Alava and Euskadi. With regard to Basque contemporary history, I Current Research 5 would mention my books Los problemas de la 2010 Conference 6 In 1987 I obtained a Ph.D. in History from autonomía vasca en el siglo XX (Problems of the University of the Basque Country, Basque Autonomy in the Twentieth Century) Highlights 7 where I’ve been employed since then: (Oñate, MVI, 1991), Trabajo, diversión y vida Bieter Grant 8 first in the School of Social Sciences and cotidiana. -

The Basques and Announcement of a Publication

Center for Basque Studies Basque Classics Series, No. 9 Selected Basque Writings: The Basques and Announcement of a Publication Wilhelm von Humboldt With an Introduction by Iñaki Zabaleta Gorrotxategi Translated by Andreas Corcoran Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada This book was published with generous financial support obtained by the Association of Friends of the Center for Basque Studies from the Provincial Government of Bizkaia. Basque Classics Series, No. 9 Series Editors: William A. Douglass, Gregorio Monreal, and Pello Salaburu Center for Basque Studies University of Nevada, Reno Reno, Nevada 89557 http://basque.unr.edu Copyright © 2013 by the Center for Basque Studies All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Cover and series design © 2013 by Jose Luis Agote Cover painting: “Aurresku ante la Iglesia” [Aurresku in front of Church] by José Arrúe. © Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa–Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Humboldt, Wilhelm, Freiherr von, 1767-1835. Selected basque writings : the Basques and announcement of a publication / Willhelm von Humboldt with an Introduction by Inaki Zabaleta Gorrotxategi ; translated by Andreas Corcoran. pages cm. -- (Basque classics series, no. 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. Summary: “Classic texts on the Basque people and language by the German man of letters Wilhelm von Humboldt with a new scholarly introduction to his Basque works”-- Provided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-935709-44-2 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-935709-45-9 (cloth) 1. Basques--History. 2. Basques--Social life and customs. 3. Basque language I. Title. GN549.B3H85 2013 305.899’92--dc23 2013036442 Contents Note on Basque Orthography ..................................... -

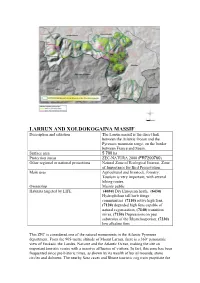

Larrun and Xoldokogaina Massif

LARRUN AND XOLDOKOGAINA MASSIF Description and situation The Larrun massif is the direct link between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pyrenees mountain range, on the border between France and Spain. Surface area 5 700 ha Protection status ZEC-NATURA 2000 (FR7200760) Other regional or national protections Natural Zone of Ecological Interest, Zone of Importance for Bird Preservation. Main uses Agricultural and livestock, forestry. Tourism is very important, with several hiking routes. Ownership Mainly public Habitats targeted by LIFE (4030) Dry European heath, (6430) Hydrophilous tall herb fringe communities (7110) active high fens, (7120) degraded high fens capable of natural regeneration, (7140) transition mires, (7150) Depressions on peat substrates of the Rhynchosporion, (7230) low alkaline fens This ZEC is considered one of the natural monuments in the Atlantic Pyrenees department. From the 905-metre altitude of Mount Larrun, there is a 360º panoramic view of Euskadi, the Landes, Navarre and the Atlantic Ocean, making the site an important touristic centre with a massive affluence of visitors. In fact, this zone has been frequented since pre-historic times, as shown by its wealth of burial mounds, stone circles and dolmens. The nearby Sara caves and Rhune touristic cog train propitiate the presence of tourists in the zone all year long. The climate is Atlantic, due to the ocean's proximity to it, with abundant precipitation year-round. 66% of the surface area is occupied by mountain pastures, and 25% by deciduous forests. Marshes and fens are also present in the area. Of the 30 natural habitats described in this site, 22 are on the list of community interest, and seven of them are considered priority. -

Matching National Stereotypes? Eating and Drinking in the Basque Borderland

A. Leizaola: Matching national stereotypes? Eating and drinking in the Basque borderland Matching national stereotypes? Eating and drinking in the Basque borderland Aitzpea Leizaola University of the Basque Country, [email protected] ABSTRACT: Focusing on tourism practices, this article discusses the role of food in the construction and reconstruction of identities and stereotypes in the Basque borderland. Borderlands, as places where national identities meet and perceptions of otherness merge, offer an interest- ing perspective on how identities are enacted. In the Basque Country, food in general and Basque cuisine in particular are considered significant markers of identity as well as hall- marks of tradition. Now a major tourist destination, thousands of Spaniards come to the Basque Country to enjoy the tastes of the much-praised Basque cuisine. At the same time, many French tourists come to the Basque borderland in search of Spanish experiences, including food. Thus, border tourism provides differing representations of this issue. Draw- ing from ethnographic data, different examples of the ways in which specific dishes and drinks come to conform to stereotypes of national identities will be presented. The analysis of food consumption patterns and their symbolic representation in the borderland offers a stimulating context in which to study how these images match stereotypes of national identity, but also contribute to the creation of new aspects of identity. KEY WORDS: food and identity, national stereotypes, border, tourism, Basque cuisine. Introduction Food plays a central role in the construction of identities. Both cooking and food con- sumption have long been considered identity markers to the point that some scholars talk of ‘alimentary identities’ (Bruegel and Laurioux 2002). -

Annual Report the Royal Academy of the Basque Language (Euskaltzaindia)

Annual Report The Royal Academy of the Basque Language (Euskaltzaindia) 2006 Bilbao, 2007 Introduction 2006 was an eventful year for Euskaltzaindia, the Royal Academy of the Basque Language. Changes to the Academy’s internal regulations, unanymously approved at Euskaltzaindia’s internal conference held at Argomaiz in 2005, came into effect in 2006 ushering in for the first time the creation of the figure of Emeritus Member of the Academy. Six full academy members over 75 years of age, Jose Antonio Arana Martija, Piarres Xarritton, Xabier Diharce “Iratzeder”, Jean Haritschelhar, Emile Larre and Antonio Zavala, entered the Emeritus category while retaining their former privileges as full members, providing they attend meetings. Sadly, the year deprived us of Patxi Altuna, full member of Euskaltzaindia, and Gaizka Barandiaran and Jose Mari Etxaburu “Kamiñazpi”, corresponding members, who passed away in 2006 and whose presence among us will be sorely missed. In the course of Euskaltzaindia’s ongoing process of self-rejuvenation, three new academy members were appointed during the year: Jose Irazu “Bernardo Atxaga”, Mikel Zalbide and Andoni Sagarna. Although all three hail from the same province, Gipuzkoa, they differ widely in professional backgrounds, and we look forward to the expertise they will contribute to the Basque Language Academy in the fields of literary production, educational administration and computer science, respectively. Two full academy members admitted the previous year delivered their inaugural lectures this year, Ana Toledo in Antzuola (in the Deba Valley), and Patxi Salaberri in Uxue (in southern Navarre). Twenty-five new corresponding members of the Academy from different parts of our country were also appointed, in acknowledgment of and gratitude for their efforts in support of the Basque language in cooperation with Euskaltzaindia over past years, and hopefully well into the future too. -

Procès-Verbal De La Séance Du Conseil Municipal Du Vendredi 11 Décembre 2015 À 18H00

Procès-verbal de la séance du conseil municipal du vendredi 11 décembre 2015 à 18h00 M. le Maire Nous allons débuter cette séance de conseil municipal, la dernière de l’année. La tradition veut qu’après la dernière séance, nous partagions tous ensemble un verre de l’amitié, sur place, et j’invite également la presse et le public à se joindre à nous. Je propose Valérie Othaburu-Fischer comme secrétaire de cette assemblée, merci de bien vouloir procéder à l’appel. Je précise que nous n’avons pas de procès-verbal à approuver, celui de la séance du 27 novembre dernier n’est pas encore rédigé, nous l’approuverons lors de la prochaine séance du conseil. ________________________ N° 1 – FINANCES Budget général : décision modificative n° 2 Mme Ithurria, adjoint, expose : Dans le cadre de l’exécution budgétaire 2015, il convient de prévoir une décision modificative n° 2 afin d’ajuster certaines lignes comptables. A titre de provisions A la demande du Trésor Public, il convient de passer des écritures pour provisionner à 100 % des titres émis à l’encontre de : - Hélianthal : suite à la décision de la cour administrative d’appel, des crédits avaient été inscrits au budget 2015 sur le compte 673.01 afin de permettre le remboursement à l’occupant de travaux de copropriété sur le bâtiment de la Pergola pour un montant de 243.703,64 €. Aujourd’hui, il convient de constituer une provision du même montant sur le compte 6815.01, dans l’attente du règlement de la somme. - SCI Neretzat : montant de 324.493,02 € au titre de la participation pour non réalisation des aires de stationnement (PNRAS) contestée par le titulaire du permis de construire. -

Le Carnaval I Ituren Et I Bie Sie Ta (Navarre)

Le carnaval iIturen et i bie ta (Navarre) du déb siecle au lendemain de guerre civile M. O. ECHEGUT INTRODUCTION pres une longue période de léthargie forcée, les carnavals refleurissent A súr le territoire espagnol et plus particulierement au Pays Basque. C'est en assistant par hasard icelui de Saint Sebastien, en février 1983, que l'idée m'est venue d'étudier cette fete. De la ville la curiosité s'est vite tour- née vers la campagne, pour dépasser le cadre de la Communauté autonome basque et s'arreter sur deux petits villages de Navarre: Ituren (en particulier le quartier dYAurtiz)ee Zubieta. Tres vite, le projet apparemment trop limité s'est avéré riche et complexe. Les articles et les ouvrages généraux sur ce the- me n'en donnaient qu'une vision incomplete. 11 a fallu aller plus loin, ne pas se contenter de l'écrit mais s'intégrer dans la vie de ces deux localités rurales. Trois séjours m'ont permis de sortir des chemins battus, de prendre du recul par rapport ice que j'avais pu lire. J'avais initialement choisi de traiter du carnaval au début du siecle. Mais en fouillant dans les souvenirs des gens, je me suis apercue que la période postérieure ila guerre civile ne constituait pas une rupture. Au contraire elle marquait une évolution, des changements dans la fete meme. Tout était donc ireconsidérer. L'étude ne parlera donc que de ce siecle. Elle passera sous silence le pro- bleme délicat des origines de ce carnaval. En l'absence de documents sérieux il aurait été difficile de procéder autrement.