Father Confessors and Clerical Intervention in Witch-Trials in Seventeenth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murder by Poison in Scotland During the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Merry, Karen Jane (2010) Murder by poison in Scotland during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2225/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Murder by Poison in Scotland During the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Karen Jane Merry Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Law Department of Forensic Medicine Faculty of Law, Business and Social Science Faculty of Medicine © Karen Jane Merry July 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the history of murder by poison in Scotland during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in the context of the development of the law in relation to the sale and regulation of poisons, and the growth of medical jurisprudence and chemical testing for poisons. The enquiry focuses on six commonly used poisons. Each chapter is followed by a table of cases and appendices on the relative scientific tests and post-mortem appearances. The various difficulties in testing for these poisons in murder and attempted murder cases during the period are discussed and the verdicts reached by juries in poisoning trials considered. -

Poisoned Relations: Medicine, Sorcery, and Poison Trials in the Contested Atlantic, 1680-1850

POISONED RELATIONS: MEDICINE, SORCERY, AND POISON TRIALS IN THE CONTESTED ATLANTIC, 1680-1850 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Chelsea L. Berry, B.A. Washington, DC March 25, 2019 Copyright 2019 by Chelsea L. Berry All Rights Reserved ii POISONED RELATIONS: MEDICINE, SORCERY, AND POISON TRIALS IN THE CONTESTED ATLANTIC, 1680-1850 Chelsea L. Berry, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Alison Games, Ph.D. ABSTRACT From 1680 to 1850, courts in the slave societies of the western Atlantic tried hundreds of free and enslaved people of African descent for poisoning others, often through sorcery. As events, poison accusations were active sites for the contestation of ideas about health, healing, and malevolent powers. Many of these cases centered on the activities of black medical practitioners. This thesis explores changes in ideas about poison through the wave of poison cases over this 170-year period and the many different people who made these changes and were bound up these cases. It analyzes over five hundred investigations and trials in Virginia, Bahia, Martinique, and the Dutch Guianas—each vastly different slave societies that varied widely in their conditions of enslaved labor, legal systems, and histories. It is these differences that make the shared patterns in the emergence, growth, and decline of poison cases, and of the relative importance of African medical practitioners within them, so intriguing. Across these four locations, there was a specific, temporally bounded, and widely shared relationship between poison, medicine, and sorcery in this period. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

A FACIE INIMICI: LA DIMENSIÓN POLÍTICA DE LA DEMONOLOGÍA CRISTIANA EN EL FORTALITIUM FIDEI DE ALONSO DE ESPINA (CASTILLA, SIGLO XV) * ‘A facie inimici’: The Political Dimension of Christian Demonology in Alonso de Espina’s Fortalitium Fidei (Castile, 15th Century) Constanza CAVALLERO** Universidad de Buenos Aires RESUMEN:El presente trabajo se ocupa de reconstruir el lazo que torna inseparables la cuestión demonológica y la dimensión estrictamente “política” –aislable únicamente a efectos analíticos– en la sociedad castellana del siglo XV. A partir del estudio del Fortalitium fidei de Alonso de Espina, se intenta definir en qué medida el discurso demo- nológico, incluso en su versión “moderada”, opera como criterio político por antonomasia en la época y como el lenguaje que permite identificar enemigos, zanjar conflictos y, también, declarar batallas y clausurar otras posibles. Tomando como punto de partida el criterio político expuesto por el discutido jurista alemán Carl Schmitt –esto es, la contraposición Freund-Feind–, se analiza el vínculo medular establecido entre el demonio y los restantes enemigos de la ecclesia combatidos por Espina: herejes judaizantes, judíos y sarracenos. El presente análisis permite no sólo ejemplificar la potencialidad política de la demonología cristiana sino también desplegar las particularidades del discurso sobre el demonio del fraile castellano Alonso de Espina. PALABRAS CLAVE: Demonología. Política. Judíos. Herejes judaizantes. Sarracenos. * Fecha de recepción del artículo: 2011-03-18. Comunicación de evaluación al autor: 2011-07-21. Versión definitiva: 2011-07-27. Fecha de publicación: 2012-06-30. ** Licenciada en Historia. Profesora de la Universidad de Buenos Aires. Becaria de posgrado del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). -

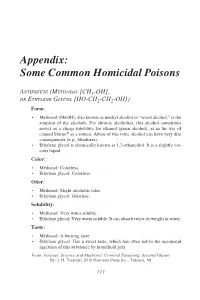

Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons

Appendix 111 Appendix: Some Common Homicidal Poisons ANTIFREEZE (METHANOL [CH3-OH], OR ETHYLENE GLYCOL [HO-CH2-CH2-OH]) Form: • Methanol (MeOH), also known as methyl alcohol or “wood alcohol,” is the simplest of the alcohols. For chronic alcoholics, this alcohol sometimes serves as a cheap substitute for ethanol (grain alcohol), as in the use of canned Sterno® as a source. Abuse of this toxic alcohol can have very dire consequences (e.g., blindness). • Ethylene glycol is chemically known as 1,2-ethanediol. It is a slightly vis- cous liquid. Color: • Methanol: Colorless. • Ethylene glycol: Colorless. Odor: • Methanol: Slight alcoholic odor. • Ethylene glycol: Odorless. Solubility: • Methanol: Very water soluble. • Ethylene glycol: Very water soluble. It can absorb twice its weight in water. Taste: • Methanol: A burning taste. • Ethylene glycol: Has a sweet taste, which has often led to the accidental ingestion of this substance by household pets. From: Forensic Science and Medicine: Criminal Poisoning, Second Edition By: J. H. Trestrail, III © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 111 112 Common Homicidal Poisons Source: • Methanol: Is a common ingredient in windshield-washing solutions, dupli- cating fluids, and paint removers and is commonly found in gas-line anti- freeze, which may be 95% (v/v) methanol. • Ethylene glycol: Is commonly found in radiator antifreeze (in a concentration of ~95% [v/v]), and antifreeze products used in heating and cooling systems. Lethal Dose: • Methanol: The fatal dose is estimated to be 30–240 mL (20–150 g). • Ethylene glycol: The approximate fatal dose of 95% ethylene glycol is esti- mated to be 1.5 mL/kg. -

L'affaire Des Poisons : Les Origines Du Satanisme

L’AFFAIRE DES POISONS : LES ORIGINES DU SATANISME par Daniel Cardinal Thèse de maîtrise présentée au département d’études anciennes et de sciences des religions de la Faculté des Arts de l’Université d’Ottawa. © Daniel Cardinal, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Résumé L’affaire des poisons est une célèbre enquête policière qui se déroula à la fin du XVIIe siècle en France sous le règne de Louis XIV. Les rapports officiels de la police de l’époque allaient dévoiler l’implication de membres des plus hautes sphères de la société française, y compris du clergé, du parlement, de la noblesse et de l’aristocratie. Mais l’enquête fut rapidement mise sous silence lorsque le roi découvrit l’implication de son ancienne maitresse en titre, la marquise de Montespan, avec qui il avait passé neuf ans de sa vie. Le nom de la dame fut mentionné par de nombreux témoins qui l’impliquèrent dans plusieurs méfaits, dont l’achat et l’utilisation de philtres d’amour et de divers poisons. Mais pis encore, Montespan fut compromise dans des cérémonies de nature blasphématoires organisées en secret par une devineresse du nom de Catherine Montvoisin - dites la Voisin - et son complice, l’abbé Étienne Guibourg. Ces rituels allaient plus tard prendre le nom de messe noire et inspirer une nouvelle forme de religiosité qui allait prendre le nom de satanisme. À partir des éléments révélés durant l’enquête de l’affaire des poisons, le satanisme allait pour la première fois se distinguer des pratiques de la sorcellerie et de la magie rituelle et se définir en tant que système de croyances. -

Folke Gernert Divination on Stage

Folke Gernert Divination on stage Folke Gernert Divination on stage Prophetic body signs in early modern theatre in Spain and Europe Publication funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) ISBN 978-3-11-069574-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-069575-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-073480-5 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110695755 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950024 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Folke Gernert, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover image: Georges de La Tour (ca. 1630), “The Fortune Teller”, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons: File:Georges de La Tour 016.jpg. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements The present book is mainly an English translation of the chapters about theatre of my monograph on the textualization of physiognomic lore in Spanish Golden Age literature together with an article about birthmarks in Calderón: Gernert, Folke. Lecturas del cuerpo. Fisiognomía y literatura en la España áurea.Salamanca: Universidad, 2018. Gernert, Folke. “La devoción de la Cruz desde la fisiognomía. La violencia de Eusebio entre predeterminación y libre albedrío.” La violencia en Calderón. Ed. Gero Arnscheidt and Manfred Tietz. -

MONTSÉGUR: a « CATHAR CITADEL » Puilaurens Quéribus

MONTSÉGUR: A « CATHAR CITADEL » Puilaurens Quéribus Peyrepertuse Puivert MAP OF THE CATHAR COUNTRY Robert Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, Oxford, Blackwell, 2007. Socially sanctioned violence directed through established governmental, judicial and social institutions against groups of people defined by general characteristics such as race (Jews), religion or way of life (sodomites / gays). Which often led to their execution on the stake Burning of the knight Hohenburg and his valet, Zurich, 1482 Evolution of the target groups from the 13th to the 17th century: Cathars Knights Templars Joan of Arc The witch-hunt Demoniacs 1208. Murder of Pierre de Castelnau, legate of pope Innocent III. 1209-1229 : military campaign led by Simon de Montfort 1233. Inquisitorial campaign : Pope Gregory IX gave Dominicans (the order founded by St. Dominic in 1217) the primary charter to act as Inquisitors, joined shortly after by the Franciscans Dualism or Manicheism : the world is the creation of Evil, everything material is corrupt. God rules the invisible, the spiritual Pope Innocent III excommunicating the Cathars Massacre by the crusaders Massacre of Béziers, July 1209 “Kill them all, God will know his own” Attributed to the Cistercian monk Arnaut Amaury, the pontifical legate The entire population (20000) was murdered August 1209. Siege of Carcassonne The people of Carcassonne were told that they had to leave the town. They deserted their city keeping just their shirt with them. “Not even the value of a button were they allowed to take with them” told a chronicler. In April 1210, a procession of about 100 men arrived from the fortified town of Bram, twenty-five miles away, that had yielded to Simon de Montfort. -

Prologue 1 Witchcraft in Context: Histories and Historiographies

Notes Prologue 1. APP AM Kalisz, I/158, pp. 347–60. 2. R. Briggs, ‘ “Many Reasons Why”: Witchcraft and the Problem of Multiple Explanation’, in J. Barry, M. Hester and G. Roberts (eds), Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe: Studies in Culture and Belief (Cambridge, 1998), p. 53. 3. See M. Zakrzewska, Procesy o czary w Lublinie w XVII i XVIII w. (Łódź, 1947), p. 3; J. Wijaczka, ‘Procesy o czary w regionie świętokrzyskim w XVII–XVIII wieku’, in J. Wijaczka (ed.), Z przeszłości regionu świętokrzyskiego od XVI do XX wieku. Materiały konferencji naukowej, Kielce, 8 kwietnia 2003 (Kielce, 2003); and idem, Procesy o czary w Prusach Książęcych (Brandenburskich) w XVI–XVIII wieku (Toruń, 2007). 4. F. Spee, Cautio criminalis seu de processibus contra sagas (Frankfurt, 1632), and Czarownica powołana, abo krótka nauka y przestroga z strony czarownic... (Poznań, 1639). 5. M. Bogucka, Women in Early Modern Poland, against the European Background (Aldershot, 2004), pp. 106–9; M. Pilaszek, Procesy o czary w Polsce w wiekach XV–XVIII (Cracow, 2008). 6. B. Baranowski, Procesy czarownic w Polsce w XVII i XVIII w. (Łódź, 1952). 7. S. Clark, Thinking with Demons (Oxford, 1999 [1997]); Briggs, ‘Many Reasons Why’; and A. Rowlands, ‘Telling Witchcraft Stories: New Perspectives on Witchcraft and Witches in the Early Modern Period’, Gender and History 10, no. 2 (1998), 294–302. 1 Witchcraft in Context: Histories and Historiographies 1. R. Briggs, Witches and Neighbours (London, 1996), p. 4. 2. For a better insight into Polish history between 1500–1800 see N. Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland (2 vols, Oxford, [1981] 1991); R.I. -

Potions, Poisons and •Œinheritance Powdersâ•Š

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Chapman University Digital Commons Voces Novae Volume 4 Article 2 2018 Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders”: How Chemical Discourses Entangled 17th Century France in the Brinvilliers Trial and the Poison Affair Erika Carroll Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Carroll, Erika (2018) "Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders”: How Chemical Discourses Entangled 17th Century France in the Brinvilliers Trial and the Poison Affair," Voces Novae: Vol. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol4/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Carroll: Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders”: How Chemical Discours Potions, Poisons and “Inheritance Powders” Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Carroll Potions, Poisons and "Inheritance Powders": How Chemical Discourses Entangled 17th Century France in the Brinvilliers Trial and the Poison Affair. Erika Carroll The trial of the Marquise de Brinvilliers for poisoning her father and her two brothers has long attracted the attention of historians as a prelude to the more famous Affair of the Poisons two years later. At the Marquise' execution, famed seventeenth-century chronicler Madame de Sevigné commented that her "ashes were to the winds, so that we shall breathe her, and ...we shall develop a poisoning urge which will astonish us all."[1] Madame de Sévingé's prediction was correct; France did develop a "poisoning urge" as a result of a growing interest in chemicals. -

Thin Black Line: the Order of St Cecil

Thin Black Line The Order of Saint Cecil Thin Black Line The Order of Saint Cecil Written by Chad Underkoffl er Illustrations by Christian N. St. Pierre Produced by Jeff Tidball Published by John Nephew Special Thanks to J. Andrew Byers and Kenneth Hite Unknown Armies Created by Greg Stolze and John Tynes A Supplement For Digital Edition 1.0. With the exception of any and all previously published elements of the Unknown Armies intellectual property (which are all ©1998-02 and ™ Greg Stolze & John Tynes) this work is ©2013 Trident, Inc. The Atlas Games logo is ©2013 and ™ Trident, Inc d/b/a Atlas Games and John Nephew. All rights reserved worldwide. Except for purposes of review, no portions of this work may be reproduced by any means without the permission of the relevant copyright holders. This is a work of fiction. Any similarity with actual people or events, past or present, is purely coincidental and unintentional. Part 1: The Light of Truth Blinds The Legend of St. Cecil The Moor looked at me with his sorcerous eyes. RTFM “You belong to my servants” said the Moor, and unleashed his demonic spirits upon me. References I was drowned under the assault. Spirits clawed This supplement contains lots of references to their way into my body and my mind—but existing Unknown Armies material. For easy not my soul. It was days, it was weeks, it was reading, most are abbreviated. months of unchristian behavior. It was wrong. † AOTM: Ascension of the Magdalene Still, a part of me fought against † BT: Break Today his unnatural dominance. -

Read- Ings in Eco- Extrem- Ism #2

Atassa: Read- ings in Eco- extrem- ism #2 on the cover: “The importance of boundaries and the circle and cross motif cropped up frequently in the decoration of ceremonial gorgets worn by Mississippian chiefs or priests in sacred ceremonies. Figure 3 depicts such a gorget, and it shows that the space beyond the orderly sacred circle was filled with horrible anomalous creatures who embodied the chaos and power of the outside world. By mixing the Underworld (a serpent’s body), the Upper World (an eagle’s wings), and This World (a panther’s head), the creatures violated the separation of the planes that was necessary if bal- ance was to be maintained. Moreover, the representation of male and female genitalia in the circular and elliptical designs that covered their serpentine bodies suggests the equally terrible consequences of mixing genders. Such monsters offered people a ter- rifying reminder of the need to follow prescribed social conventions to save their world and themselves. From the sleepy rivers and fetid swamps that represented the pathways between This World and the Underworld to the dark arboreal embrace of the forests beyond the pale of human habitation, the outside world that surrounded the Choctaws was home to many terrible creatures. Those who ventured beyond the circle’s safe confines could expect to encounter monsters like the Nalusa Falaya, the Long Evil Being. Its beady eyes, set in a small shriveled head, peered over a protruding nose and searched the night for hunters. When it spotted prey the monster crept up behind the hunting parties and called to them. -

Satan Rehabilitated? a Study Into Satanism in the Nineteenth Century Van Luijk, R.B

Tilburg University Satan rehabilitated? A study into satanism in the nineteenth century van Luijk, R.B. Publication date: 2013 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): van Luijk, R. B. (2013). Satan rehabilitated? A study into satanism in the nineteenth century. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. sep. 2021 SATAN REHABILITATED? A Study into Satanism during the Nineteenth Century Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University, op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 19 april 2013 om 14.15 uur door Ruben Benjamin van Luijk geboren op 9 juli 1976 te Rotterdam 2 Promotores: Prof.