Esfandiary Ku 0099D 15854 D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranian Women's Quest for Self-Liberation Through

IRANIAN WOMEN’S QUEST FOR SELF-LIBERATION THROUGH THE INTERNET AND SOCIAL MEDIA: AN EMANCIPATORY PEDAGOGY TANNAZ ZARGARIAN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATION YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO December 2019 © [Tannaz Zargarian, 2019] i Abstract This dissertation examines the discourse of body autonomy among Iranian women. It approaches the discourse of body autonomy by deconstructing veiling, public mobility, and sexuality, while considering the impact of society, history, religion, and culture. Although there are many important scholarly works on Iranian women and human rights that explore women’s civil rights and freedom of individuality in relation to the hijab, family law, and sexuality, the absence of work on the discourse of body autonomy—the most fundamental human right—has created a deficiency in the field. My research examines the discourse of body autonomy in the context of liberation among Iranian women while also assessing the role of the internet as informal emancipatory educational tools. To explore the discourse of body autonomy, I draw upon critical and transnational feminist theory and the theoretical frameworks of Derayeh, Foucault, Shahidian, Bayat, Mauss, and Freire. Additionally, in-depth semi-structured interviews with Iranian women aged 26 to 42 in Iran support my analysis of the practice and understanding of body autonomy personally, on the internet, and social media. The results identify and explicate some of the major factors affecting the practice and awareness of body autonomy, particularly in relation to the goal of liberation for Iranian women. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

Jamal Rostami

CURRICULUM VITAE JAFAR KHADEMI HAMIDI, Ph.D. Mining Eng. Dept., Faculty of Engineering Phone: +98 21-82884364 Tarbiat Modares University Fax: +98 21-82884324 Jalal Ale Ahmad Highway, Nasr Bridge Email: [email protected] P.O. Box: 14115-143, Tehran, Iran http://www.modares.ac.ir/~jafarkhademi SUMMARY OF EXPERIENCE Jafar Khademi Hamidi received his PhD degree in Mining Engineering from Amirkabir University of Technology (Tehran Polytechnic) in January 2011 with dissertation entitled "A model for hard rock TBM performance prediction". As a PhD student in Tehran Polytechnic, he was a recipient of several competitive awards that include honored and top-rank recognition student, selected young researcher, sabbatical opportunity and INEF awards. He worked as a consultant in the area of underground construction, mechanical excavation, geotechnical investigations, construction bid preparation, tunneling in difficult ground conditions and longwall coal mine design between 2006 and 2013. He has started faculty job at Tarbiat Modares University (TMU) from spring 2012. Currently, as an Assistant Professor of Mining Engineering and founder of Mechanized Excavation Laboratory in TMU, he is to pursue basic and applied researches in the field of mechanical mining and excavation. RESEARCH INTEREST Underground mining (geotechnical engineering, design and planning, risk analysis) Mechanical mining and excavation (rock drillability/cuttability/boreability, design and fabrication of rock cuttability index tests, rock abrasion and tool wear) GIS -

US Television Icon Mary Tyler Moore Dead at 80

Lifestyle FRIDAY, JANUARY 27, 2017 Iran actress to boycott Oscars over 'racist' Trump visa ban he Iranian star of Oscar-nominated film foreign language film at the Academy "The Salesman" said yesterday she Awards, which take place next month. Twould boycott the awards in protest at Farhadi won an Oscar in 2012 for his film "A President Donald Trump's "racist" ban on Separation". Visa applications from Iraq, Syria, Muslim immigrants. "Trump's visa ban for Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Yemen are all Iranians is racist. Whether this will include a expected to be stopped for a month under a cultural event or not, I won't attend the draft executive order published in the #AcademyAwards 2017 in protest," tweeted Washington Post and New York Times. The Taraneh Alidoosti, the film's 33-year-old lead draft order also seeks to suspend the US actress. Trump is reportedly poised to stop refugee program for four months as officials visas for travellers from seven Muslim coun- draw up a list of low risk countries. —AFP tries, including Iran, for 30 days. He told ABC News on Wednesday that his plan was not a "Muslim ban", but targeted This image released by Cohen Media countries that "have tremendous terror." "The group shows Shahab Hosseini, left, Salesman", directed by acclaimed Iranian film- and Taraneh Alidoosti in a scene maker Asghar Farhadi is nominated for best from "The Salesman." — AP US television icon Mary Tyler Moore dead at 80 egendary actress Mary Tyler Moore, who delighted a genera- 'Effortless piece of cake' also married in real life. -

Sydney Film Festival 6-17 June 2012 Program Launch

MEDIA RELEASE Wednesday 9 May, 2012 Sydney Film Festival 6-17 June 2012 Program Launch The 59th Sydney Film Festival program was officially launched today by The Hon Barry O’Farrell, MP, Premier of NSW. “It is with great pleasure that I welcome the new Sydney Film Festival Director, Nashen Moodley, to present the 2012 Sydney Film Festival program,” said NSW Premier Barry O’Farrell. “The Sydney Film Festival is a much-loved part of the arts calendar providing film-makers with a wonderful opportunity to showcase their work, as well as providing an injection into the State economy.” SFF Festival Director Nashen Moodley said, “I’m excited to present my first Sydney Film Festival program, opening with the world premiere of the uplifting Australian comedy Not Suitable for Children, a quintessentially Sydney film. The joy of a film festival is the breadth and diversity of program, and this year’s will span music documentaries, horror flicks and Bertolucci classics; and the Official Competition films made by exciting new talents and masters of the form, will continue to provoke, court controversy and broaden our understanding of the world.” “The NSW Government, through Destination NSW, is proud to support the Sydney Film Festival, one of Australia’s oldest films festivals and one of the most internationally recognised as well as a key event on the NSW Events Calendar,” said NSW Minister for Tourism, Major Events and the Arts, George Souris. “The NSW Government is committed to supporting creative industries, and the Sydney Film Festival firmly positions Sydney as Australia’s creative capital and global city for film.” This year SFF is proud to announce Blackfella Films as a new programming partner to jointly curate and present the best and newest Indigenous work from Australia and around the world. -

Habib Majidi, SMPSP © Design : Laurent Pons / Troïka CREDITS

© photos : Habib Majidi, SMPSP © Design : Laurent Pons / TROÏKA DESIGN LAURENT PONS/ TROÏKA DESIGN LAURENT PONS/ PSP M S ABIB MAJIDI, ABIB MAJIDI, H CREDITS NON CONTRACTUAL - PHOTO MEMENTO FILMS PResents official selection cannes festival SHAHAB TARANEH HOssEINI THE ALIDOOSTI SALESMAN A FILM BY ASGHAR FARHADI 125 min - 1.85 - 5.1 - Iran / France download presskit and stills on www.memento-films.com World Sales & Festivals press Vanessa Jerrom t : 06 14 83 88 82 t : +33 1 53 34 90 20 Claire Vorger [email protected] t : 06 20 10 40 56 [email protected] [email protected] http://international.memento-films.com/ t : + 33 1 42 97 42 47 SYNOPSIS Their old flat being damaged, Emad and Rana, a young couple living in Tehran, is forced to move into a new apartment. An incident linked to the previous tenant will dramatically change the couple's life. INTERVIEW WITH ASGHAR FARHADI After making THE PAST in France and in Everything depends on the viewer’s own French, why did you go back to Tehran particular preoccupations and mindset. If for THE SALESMAN? you see it as social commentary, you’ll re- When I finished THE PAST in France, I member those elements. Somebody else started to work on a story that takes place might see it as a moral tale, or from a totally in Spain. We picked the locations and different angle. What I can say is that once I wrote a complete script, without the again, this film deals with the complexity of dialogue. We discussed about the project human relations, especially within a family. -

Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran

Negotiating a Position: Women Musicians and Dancers in Post-Revolution Iran Parmis Mozafari Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Music January 2011 The candidate confIrms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 2011 The University of Leeds Parmis Mozafari Acknowledgment I would like to express my gratitude to ORSAS scholarship committee and the University of Leeds Tetly and Lupton funding committee for offering the financial support that enabled me to do this research. I would also like to thank my supervisors Professor Kevin Dawe and Dr Sita Popat for their constructive suggestions and patience. Abstract This research examines the changes in conditions of music and dance after the 1979 revolution in Iran. My focus is the restrictions imposed on women instrumentalists, dancers and singers and the ways that have confronted them. I study the social, religious, and political factors that cause restrictive attitudes towards female performers. I pay particular attention to changes in some specific musical genres and the attitudes of the government officials towards them in pre and post-revolution Iran. I have tried to demonstrate the emotional and professional effects of post-revolution boundaries on female musicians and dancers. Chapter one of this thesis is a historical overview of the position of female performers in pre-modern and contemporary Iran. -

Abstracts Electronic Edition

Societas Iranologica Europaea Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the State Hermitage Museum Russian Academy of Sciences Abstracts Electronic Edition Saint-Petersburg 2015 http://ecis8.orientalstudies.ru/ Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts CONTENTS 1. Abstracts alphabeticized by author(s) 3 A 3 B 12 C 20 D 26 E 28 F 30 G 33 H 40 I 45 J 48 K 50 L 64 M 68 N 84 O 87 P 89 R 95 S 103 T 115 V 120 W 125 Y 126 Z 130 2. Descriptions of special panels 134 3. Grouping according to timeframe, field, geographical region and special panels 138 Old Iranian 138 Middle Iranian 139 Classical Middle Ages 141 Pre-modern and Modern Periods 144 Contemporary Studies 146 Special panels 147 4. List of participants of the conference 150 2 Eighth European Conference of Iranian Studies. Abstracts Javad Abbasi Saint-Petersburg from the Perspective of Iranian Itineraries in 19th century Iran and Russia had critical and challenging relations in 19th century, well known by war, occupation and interfere from Russian side. Meantime 19th century was the era of Iranian’s involvement in European modernism and their curiosity for exploring new world. Consequently many Iranians, as official agents or explorers, traveled to Europe and Russia, including San Petersburg. Writing their itineraries, these travelers left behind a wealthy literature about their observations and considerations. San Petersburg, as the capital city of Russian Empire and also as a desirable station for travelers, was one of the most important destination for these itinerary writers. The focus of present paper is on the descriptions of these travelers about the features of San Petersburg in a comparative perspective. -

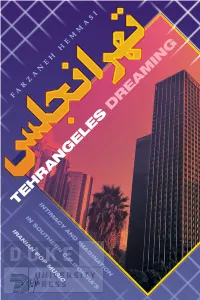

Read the Introduction

Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING IRANIAN POP MUSIC IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION TEHRANGELES DREAMING Farzaneh hemmasi TEHRANGELES DREAMING INTIMACY AND IMAGINATION IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA’S IRANIAN POP MUSIC Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Portrait Text Regular and Helvetica Neue Extended by Copperline Book Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Hemmasi, Farzaneh, [date] author. Title: Tehrangeles dreaming : intimacy and imagination in Southern California’s Iranian pop music / Farzaneh Hemmasi. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019041096 (print) lccn 2019041097 (ebook) isbn 9781478007906 (hardcover) isbn 9781478008361 (paperback) isbn 9781478012009 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Music. | Popular music—California—Los Angeles—History and criticism. | Iranians—California—Los Angeles—Ethnic identity. | Iranian diaspora. | Popular music—Iran— History and criticism. | Music—Political aspects—Iran— History—20th century. Classification:lcc ml3477.8.l67 h46 2020 (print) | lcc ml3477.8.l67 (ebook) | ddc 781.63089/915507949—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041096 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041097 Cover art: Downtown skyline, Los Angeles, California, c. 1990. gala Images Archive/Alamy Stock Photo. To my mother and father vi chapter One CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 38 1. The Capital of 6/8 67 2. Iranian Popular Music and History: Views from Tehrangeles 98 3. Expatriate Erotics, Homeland Moralities 122 4. Iran as a Singing Woman 153 5. A Nation in Recovery 186 Conclusion: Forty Years 201 Notes 223 References 235 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There is no way to fully acknowledge the contributions of research interlocutors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family members to this book, but I will try. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

VOICES OF A REBELLIOUS GENERATION: CULTURAL AND POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN IRAN’S UNDERGROUND ROCK MUSIC By SHABNAM GOLI A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Shabnam Goli I dedicate this thesis to my soul mate, Alireza Pourreza, for his unconditional love and support. I owe this achievement to you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. I thank my committee chair, Dr. Larry Crook, for his continuous guidance and encouragement during these three years. I thank you for believing in me and giving me the possibility for growing intellectually and musically. I am very thankful to my committee member, Dr. Welson Tremura, who devoted numerous hours of endless assistance to my research. I thank you for mentoring me and dedicating your kind help and patience to my work. I also thank my professors at the University of Florida, Dr. Silvio dos Santos, Dr. Jennifer Smith, and Dr. Jennifer Thomas, who taught me how to think and how to prosper in my academic life. Furthermore, I express my sincere gratitude to all the informants who agreed to participate in several hours of online and telephone interviews despite all their difficulties, and generously shared their priceless knowledge and experience with me. I thank Alireza Pourreza, Aldoush Alpanian, Davood Ajir, Ali Baghfar, Maryam Asadi, Mana Neyestani, Arash Sobhani, ElectroqutE band members, Shahyar Kabiri, Hooman Ajdari, Arya Karnafi, Ebrahim Nabavi, and Babak Chaman Ara for all their assistance and support. -

Ceramics Lab for People with Special Needs

FEBRUARY 27, 2021 MMirror-SpeirTHEror-SpeARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXXI, NO. 32, Issue 4674 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 IN BRIEF Erdogan to Attend Grey Wolves School Groundbreaking in Shushi ISTANBUL (PanARMENIAN.Net) — Turkish and Azerbaijani Presidents Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Ilham Aliyev, respectively, are expected to attend the groundbreak ceremony for a school funded by Grey Wolves leader Devlet Bahçeli in Shushi, an Armenian city in Nagorno-Karabakh that has come under Azerbaijan's control in the recent 44-day war, media reports from Turkish reveal. Yusuf Ziya Günaydın, an aide to Bahçeli, broke the news last week, Hurriyet reports. The Grey Wolves are closely linked to the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), which has a political alliance with Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). The Grey Wolves are regarded as the militant wing of the MHP and are known for causing havoc throughout the world. Prosecutors in Turkey To Strip Immunity of MPs, Including Paylan A throng of demonstrators on Saturday, February 20 ANKARA (Bianet) — The Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office has prepared summaries of pro- Dozens Detained at Anti-Government Protest in Yerevan ceedings for nine lawmakers from the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), seeking to lift their leg- islative immunity. YEREVAN (RFE/RL) — Dozens of members and supporters of The high-rise was cordoned off in the morning by scores of riot The HDP lawmakers, along with 99 other defen- an Armenian opposition alliance were detained on Tuesday, police that kept protesters at bay and enabled Pashinyan to enter dants, are facing life sentences for having allegedly February 23, as they attempted to stop Prime Minister Nikol it and hold a meeting with senior officials from the Armenian organized the deadly “Kobane protests” in Kurdish- Pashinyan from entering a government building in Yerevan. -

Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström

Online version of Music Media Multiculture. Changing Musicscapes. by Dan Lundberg, Krister Malm & Owe Ronström Stockholm, Svenskt visarkiv, 2003 Publications issued by Svenskt visarkiv 18 Translated by Kristina Radford & Andrew Coultard Illustrations: Ann Ahlbom Sundqvist For additional material, go to http://old.visarkiv.se/online/online_mmm.html Contents Preface.................................................................................................. 9 AIMS, THEMES AND TERMS Aims, emes and Terms...................................................................... 13 Music as Objective and Means— Expression and Cause, · Assumptions and Questions, e Production of Difference ............................................................... 20 Class and Ethnicity, · From Similarity to Difference, · Expressive Forms and Aesthet- icisation, Visibility .............................................................................................. 27 Cultural Brand-naming, · Representative Symbols, Diversity and Multiculture ................................................................... 33 A Tradition of Liberal ought, · e Anthropological Concept of Culture and Post- modern Politics of Identity, · Confusion, Individuals, Groupings, Institutions ..................................................... 44 Individuals, · Groupings, · Institutions, Doers, Knowers, Makers ...................................................................... 50 Arenas .................................................................................................