Regional Highlight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Travis Major – Curriculum Vitae

Travis Major – Curriculum Vitae Travis Major Contact University of California – Los Angeles (785)218-8183 Department of Linguistics [email protected] 3125 Campbell Hall Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543 Education Present PhD student in Linguistics University of California Los Angeles 2014 Master of Arts in Linguistics University of Kansas Thesis title: Syntactic Islands in Uyghur Thesis committee: Harold Torrence, Jason Kandybowicz, Arienne Dwyer 2011 B.A. Linguistics, English University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2011 Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Certificate University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Adult/University Level TESOL Undergraduate Certificate Program Interests Syntax, semantics, field linguistics, morphology, comparative syntax Conference Presentations 2017 Wh Interrogatives in Ibibio: Movement, Agreement and Complementizers (with Harold Torrence). The 48th Annual Conference of African Linguistics. Bloomington, Indiana. The role of logophoricity in Turkic Anaphora (with Sözen Ozkan). The 91st Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America. Austin, TX. 2016 Anaphora in two Turkic languages: Condition A is not enough (with Sözen Ozkan). Turkish, Turkic, and Languages of Turkey 2. Bloomington, Indiana. Serial Verb Constructions in Ibibio. The 47th Annual Conference of African Linguistics. Berkeley, CA. 1 Travis Major – Curriculum Vitae Conference Presentations 2016 Verb and Predicate Coordination in Ibibio (With Phillip Duncan and Mfon Udoinyang).The 47th Annual Conference of African Linguistics. Berkeley, CA. 2015 Uyghur Contrastive Polarity Questions: A case of verb-stranding “TP- ellipsis”. Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics 12; New Britain, CT. An ERP investigation of the role of prediction and individual differences in semantic priming (With L. Covey, C. Coughlin, A. Johnson, X. Yang, C. Siew, and R. Fiorentino). -

Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map

SVENSKA FORSKNINGSINSTITUTET I ISTANBUL SWEDISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE IN ISTANBUL SKRIFTER — PUBLICATIONS 5 _________________________________________________ Lars Johanson Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map Svenska Forskningsinstitutet i Istanbul Stockholm 2001 Published with fõnancial support from Magn. Bergvalls Stiftelse. © Lars Johanson Cover: Carte de l’Asie ... par I. M. Hasius, dessinée par Aug. Gottl. Boehmius. Nürnberg: Héritiers de Homann 1744 (photo: Royal Library, Stockholm). Universitetstryckeriet, Uppsala 2001 ISBN 91-86884-10-7 Prefatory Note The present publication contains a considerably expanded version of a lecture delivered in Stockholm by Professor Lars Johanson, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, on the occasion of the ninetieth birth- day of Professor Gunnar Jarring on October 20, 1997. This inaugu- rated the “Jarring Lectures” series arranged by the Swedish Research Institute of Istanbul (SFII), and it is planned that, after a second lec- ture by Professor Staffan Rosén in 1999 and a third one by Dr. Bernt Brendemoen in 2000, the series will continue on a regular, annual, basis. The Editors Discoveries on the Turkic Linguistic Map Linguistic documentation in the field The topic of the present contribution, dedicated to my dear and admired colleague Gunnar Jarring, is linguistic fõeld research, journeys of discovery aiming to draw the map of the Turkic linguistic world in a more detailed and adequate way than done before. The survey will start with the period of the classical pioneering achievements, particu- larly from the perspective of Scandinavian Turcology. It will then pro- ceed to current aspects of language documentation, commenting brief- ly on a number of ongoing projects that the author is particularly fami- liar with. -

Uyghur Language Under Attack: the Myth of “Bilingual” Education in the People's Republic of China

Uyghur Language Under Attack: The Myth of “Bilingual” Education in the People’s Republic of China Uyghur Human Rights Project July 24, 2007 I. Overview of the Report new “bilingual” education imperative is designed to transition minority students from Uyghur language is under attack in East education in their mother tongue to education Turkistan1 (also known as the Xinjiang in Chinese. The policy marks a dramatic shift Uyghur Autonomous Region or XUAR). In away from more egalitarian past policies that the past decade, and with increasing intensity provided choice for Uyghur parents in their since 2002, the People’s Republic of China children’s languages of instruction. In the (PRC) has pursued assimilationist policies PRC “bilingual” education amounts to aimed at removing Uyghur as a language of compulsory Chinese language education. instruction in East Turkistan. Employing the term “bilingual” education, the PRC is, in “Bilingual” education in East Turkistan is reality, implementing a monolingual Chinese responsible for: language education system that undermines the linguistic basis of Uyghur culture.2 The • Marginalizing Uyghur in the educational sphere with the goal of eliminating it as a language of instruction in East Turkistan. 1 Use of the term ‘East Turkistan’ does not define a • Forcing Uyghur students at levels ‘pro-independence’ position. Instead, it is used by ranging from preschool to university to Uyghurs wishing to assert their cultural distinctiveness from China proper. ‘Xinjiang’, meaning ‘new study in a second language. boundary’ or ‘new realm’, was adopted by the • Removing Uyghur children from their Manchus in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) and reflects cultural environment and placing them the perspective of those who gave it this name. -

Our 'Messy' Mother Tongue: Language Attitudes Among Urban Uyghurs and Desires for 'Purity' in the Public Sphere

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks Our ‘messy’ mother tongue: Language attitudes among urban Uyghurs and desires for ‘purity’ in the public sphere. By ©2013 Ashley C. Thompson Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ____________________________ Dr. Arienne M. Dwyer, Chairperson ____________________________ Dr. Majid Hannoum ____________________________ Dr. Carlos M. Nash Date defended: January 17, 2013 The Thesis Committee for Ashley C. Thompson certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Our ‘messy’ mother tongue: Language attitudes among urban Uyghurs and desires for ‘purity’ in the public sphere ________________________ Dr. Arienne M. Dwyer, Chairperson Date approved: February 3, 2013 ii ABSTRACT Ashley Thompson Department of Anthropology University of Kansas 2013 This thesis is a qualitative study investigating how ‘purified’ language in Uyghur- language broadcast media is interpreted by Uyghurs living in urban Ürümchi, the regional capital of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwest China. ‘Purity’ refers to the intentional avoidance of Mandarin Chinese loanwords, otherwise heard often in everyday conversations, but expunged in television news. The participants in my research, urban Uyghurs who received mother-tongue education, viewed ‘pure’ language used in broadcast media as a pedagogical tool, holding it to prescriptive standards not deemed necessary for everyday language practice. Recent education reforms have greatly decreased exposure and use of Uyghur in the classroom, and increased the importance in the work environment to be proficient in Mandarin Chinese. -

89 Annual Meeting

Meeting Handbook Linguistic Society of America American Dialect Society American Name Society North American Association for the History of the Language Sciences Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas The Association for Linguistic Evidence 89th Annual Meeting UIF+/0 7/-+Fi0N i0N XgLP(+I'L 5/hL- 7/-+Fi0N` 96 ;_AA Ti0(i-e` @\A= ANNUAL REVIEWS It’s about time. Your time. It’s time well spent. VISIT US IN BOOTH #1 LEARN ABOUT OUR NEW JOURNAL AND ENTER OUR DRAWING! New from Annual Reviews: Annual Review of Linguistics linguistics.annualreviews.org • Volume 1 • January 2015 Co-Editors: Mark Liberman, University of Pennsylvania and Barbara H. Partee, University of Massachusetts Amherst The Annual Review of Linguistics covers significant developments in the field of linguistics, including phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and their interfaces. Reviews synthesize advances in linguistic theory, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics, language change, biology and evolution of language, typology, and applications of linguistics in many domains. Complimentary online access to the first volume will be available until January 2016. TABLE OF CONTENTS: • Suppletion: Some Theoretical Implications, • Correlational Studies in Typological and Historical Jonathan David Bobaljik Linguistics, D. Robert Ladd, Seán G. Roberts, Dan Dediu • Ditransitive Constructions, Martin Haspelmath • Advances in Dialectometry, Martijn Wieling, John Nerbonne • Quotation and Advances in Understanding Syntactic • Sign Language Typology: The Contribution of Rural Sign Systems, Alexandra D'Arcy Languages, Connie de Vos, Roland Pfau • Semantics and Pragmatics of Argument Alternations, • Genetics and the Language Sciences, Simon E. Fisher, Beth Levin Sonja C. -

Uyghur Voices on Education: China’S Assimilative ‘Bilingual Education’ Policy in East Turkestan

Uyghur Voices on Education: China’s Assimilative ‘Bilingual Education’ Policy in East Turkestan A Report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project Washington, D.C. Table of Contents I. Background ..................................................................................................................................2 II. Personal Reflections on the Bilingual Education System.........................................................16 Essay 1: Reflections on min kao han education: My perception as a min kao han student on bilingual education with Chinese characteristics......................................................................16 Essay 2: Uyghur university graduates’ difficulties finding employment sends the message that “schooling is worthless” .........................................................................................................21 Essay 3. Views on the bilingual education system in East Turkestan...........................................26 Essay 4. My beloved school’s name will be wiped out from East Turkestan history...................29 III. Recommendations ...................................................................................................................31 IV. Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................33 Cover image: Uyghur students study Mandarin Chinese in Hotan Experimental Bilingual School, October 13, 2006. (Getty Images) 1 I. Background Policy Throughout the history of the People’s Republic -

The Lower Mississippi Valley As a Language Area

The Lower Mississippi Valley as a Language Area By David V. Kaufman Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Carlos M Nash ________________________________ Bartholomew Dean ________________________________ Clifton Pye ________________________________ Harold Torrence ________________________________ Andrew McKenzie Date Defended: May 30, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for David V. Kaufman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Lower Mississippi Valley as a Language Area ________________________________ Chairperson Carlos M Nash Date approved: June 9, 2014 iii Abstract It has been hypothesized that the Southeastern U.S. is a language area, or Sprachbund. However, there has been little systematic examination of the supposed features of this area. The current analysis focuses on a smaller portion of the Southeast, specifically, the Lower Mississippi Valley (LMV), and provides a systematic analysis, including the eight languages that occur in what I define as the LMV: Atakapa, Biloxi, Chitimacha, Choctaw-Chickasaw, Mobilian Trade Language (MTL), Natchez, Ofo, and Tunica. This study examines phonetic, phonological, and morphological features and ranks them according to universality and geographic extent, and lexical and semantic borrowings to assess the degree of linguistic and cultural contact. The results -

Tonogenesis in Southeastern Monguor Arienne M. Dwyer

Dwyer, Arienne M. 2008. Tonogenesis in Southeastern Monguor. In Harrison, K. David, David Rood, and Arienne Dwyer, eds. Lessons from documented endangered languages. Typological Studies in Language 78. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 111–128. Preprint Tonogenesis in Southeastern Monguor Arienne M. Dwyer University of Kansas [email protected] Dr. Arienne M. Dwyer University of Kansas Anthropology 1415 Jayhawk Blvd. - Fraser Hall Lawrence, KS 66045 USA Tel. +1 (785) 864-2649 Fax.+1 (785) 864-5224 [email protected] Italics are used for emphasis and for foreign language words. 12 pt. DoulosSIL Unicode font is used for linguistic transcriptions in IPA. Its subscripted numbers (here representing tone) are unstable, and may differently each time the document is opened. 12 pt. PMingLiU Unicode font is used for Chinese characters; 11 pt in linguistic examples. Tonogenesis in Southeastern Monguor Arienne M. Dwyer University of Kansas Abstract As the result of language contact in the northern Tibetan region, one variety of the Mongolic language Monguor (ISO 639-3: MJG) realizes prosodic accent as a rising pitch contour. Furthermore, a small number of homophones have come to be distinguished by tonal contour. Although at least two Turkic and Mongolic languages have occasionally copied the most salient tonal features of some Chinese loanwords, this is the first known example of both distinctive pitch contrasts in native lexemes, as well as default prosodic accent at the utterance level. Such an incipient tonal system offers insight into the relationship between often-contested types of prosodic accent as well as the effects of intensive language contact. Tonogenesis in Southeastern Monguor Arienne M. -

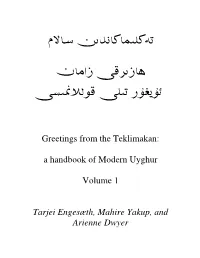

A Handbook of Modern Uyghur

ﺗﻪﻛﻠﯩﻤﺎﻛﺎﻧﺪﯨﻦ ﺳﺎﻻﻡ ھﺎﺯﯨﺮﻗﻰ ﺯﺍﻣﺎﻥ ﺋﯘﻳﻐﯘﺭ ﺗﯩﻠﻰ ﻗﻮﻟﻼﳕﯩﺴﻰ Greetings from the Teklimakan: a handbook of Modern Uyghur Volume 1 Tarjei Engesæth, Mahire Yakup, and Arienne Dwyer Teklimakandin Salam / A Handbook of Modern Uyghur (Vol. 1) Version 1.0 ©2009 by Tarjei Engesæth, Mahire Yakup and Arienne Dwyer University of Kansas Scholarworks Some rights reserved The authors grant the University of Kansas a limited, non-exclusive license to disseminate the textbook and audio through the KU ScholarWorks repository and to migrate these items for preservation purposes. Bibliographic citation: Engesæth, Tarjei, Mahire Yakup, and Arienne Dwyer. 2009. Teklimakandin Salam: hazirqi zaman Uyghur tili qollanmisi / Greetings from the Teklimakan: a handbook of Modern Uyghur. ISBN 978-1-936153-03-9 (textbook), ISBN 978-1-936153-04-6 (audio) Lawrence: University of Kansas Scholarworks. Online at: http://hdl.handle.net/1808/5624 You are free to share (to download, print, copy, distribute and transmit the work), under the following conditions: Attribution 1. — You must attribute any part or all of the work to the authors, according to the citation above. 2. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. 3. No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. ii Engesæth, Yakup & Dwyer TABLE OF CONTENTS page i-xiii ﻛﯩﺮﯨﺶ ﺳﯚز Preface What is Uyghur? Why study Uyghur? Why is this a free textbook? How to use this textbook How to enhance your learning experience Contributions of each co-author Acknowledgements Abbreviations used in this textbook References Introduction 1 ﺋﻮﻣﯘﻣﻰ ﭼﯜﺷﻪﻧﭽﻪ Uyghur Grammar 1. General Characteristics 2. Sound system 3. -

Arienne M. Dwyer

Arienne M. Dwyer University of Kansas Department of Anthropology 1415 Jayhawk Blvd. - Fraser Hall 638 Lawrence, KS 66045 USA [email protected] Tel. +1 (785) 864-2649 Co-Director, Institute for Digital Research in the Humanities , University of Kansas, 2010–. Professor of Linguistic Anthropology, University Kansas, 8/2012–. Courtesy affiliations in Linguistics and Indigenous Nations Studies, University of Kansas, 2003–. Associate Professor of Linguistic Anthropology, University of Kansas, 2008–2012. Assistant Professor of Linguistic Anthropology, University of Kansas, 2001–2008. Humboldt Scholar and Lecturer, Seminar für Orientkunde, Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, 1997–2001. EDUCATION Ph.D. in Chinese and Altaic Linguistics, University of Washington, 1996. M.A. in Chinese Language and Literature, University of Washington, 1990. B.A. in Linguistics, University of British Columbia, 1984. Fluent in Mandarin, Uyghur, German and (somewhat rusty) French; native speaker of Am. English. High intermediate competence in Japanese and NW Chinese, Salar, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh. Reading competence in Classical Chinese, Manchu, pre-13th c. Turkic, and some Russian. Learning Monguor, Wutun and ASL. RESEARCH INTERESTS Language Contact and variation (areal processes, linguistic creolization, discourse and ideologies) Digital Humanities, Media Archives, cyberinfrastructure: Computing applications, cultural practices and standards for analyzing data and representing knowledge; corpora, relational databases, XML tools, Unicode. China; Chinese Inner Asia (especially Xinjiang and Qinghai); Kyrgyzstan Language Endangerment and Revitalization; Less-commonly taught language pedagogy Sinitic, Turkic, and Mongolic languages Performance, narrative structure and ethnopoetics SPONSORED RESEARCH (all as sole P.I. unless otherwise indicated) P.I. Light verbs in Uyghur. NSF-BCS 1053152 (2011-2014). Project website: http://uyghur.ittc.ku.edu P.I. -

The State of Documentation of Kalahari Basin Languages

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 15 Refections on Language Documentation 20 Years afer Himmelmann 1998 ed. by Bradley McDonnell, Andrea L. Berez-Kroeker & Gary Holton, pp. 210–223 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ 21 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24823 Te state of documentation of Kalahari Basin languages Tom Güldemann Humboldt University Berlin Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History Jena Te Kalahari Basin is a linguistic macro-area in the south of the African continent. It has been in a protracted process of disintegration that started with the arrival of Bantu peoples from the north and accelerated dramatically with the European colonization emanating from the southwest. Before these major changes, the area hosted, and still hosts, three independent linguistic lineages, Tuu, Kx’a, and Khoe-Kwadi, that were traditionally subsumed under the spurious linguistic concept “Khoisan” but are beter viewed as forming a “Sprachbund”. Te languages have been known for their quirky and complex sound systems, notably involving click phonemes, but they also display many other rare linguistic features—a profle that until recently was documented and described very insufciently. At the same time, spoken predominantly by relatively small and socially marginalized forager groups, known under the term “San”, most languages are today, if not on the verge of extinction, at least latently endangered. Tis contribution gives an overview of their current state of documentation, which has improved considerably within the last 20 years.