V0 / Intellectuals and National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GV-Vorlage Präsident

Eine Initiative von Wissenschaft, Politik und Wirtschaft Die Eröffnung des Harnack-Hauses am 7. Mai 1929 war für Berliner Wissenschaftler, Politiker und Spitzenvertreter der Wirtschaft ein großer Tag, hatten sie doch mit vereinten Kräften erreicht, dass Berlin endlich ein Vortrags- und Begegnungszentrum für die Mitglieder der berühmten Dahlemer Institute und gleichzeitig ein Gästehaus für Wissenschaftler aus aller Welt bekam. Initiatoren des Hauses waren vor allem Adolf von Harnack und Friedrich Glum, die energisch für die Realisierung des Projektes gekämpft hatten. Der Theologe Adolf von Harnack, erster Präsident der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Robert Andrews Millikan im Harnack-Haus © Bundesarchiv Bild 102-12631 / CC-BA-SA,/Fotograf: hatte vor allem ein Ziel: Die Isolation der deutschen Georg Pahl Wissenschaft nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg zu über- winden und durch internationale Zusammenarbeit Spitzenleistungen zu ermöglichen. Harnacks Bestrebungen, ein internationales Forscher- zentrum in Dahlem aufzubauen, wurden tatkräftig unterstützt von Generaldirektor Glum, der innerhalb der KWG, bei Firmen und Privatleuten für die Idee einer internationalen Begeg- nungsstätte Werbung gemacht hatte. Im Juni 1926 beschloss der Senat der Kaiser- Wilhelm-Gesellschaft die Gründung des Harnack- Hauses - auch mit dem Ziel, Dank abzustatten für die Gastfreundschaft, die deutsche Forscher im Ausland erfahren hatten. Als wichtigste politische Paten des Harnack-Hauses stellten sich Reichsau- ßenminister Gustav Stresemann, Reichskanzler Wilhelm Marx und der einflussreiche Zentrums- Abgeordnete Georg Schreiber heraus, die der Idee Harnacks die nötige politische Lobby verschafften und öffentliche Mittel für den Bau des Hauses durchsetzten. Konkret bedeutete das: Das Reich Einweihung des Kaiser-Wilhelm-Instituts in Berlin Dahlem, 28. Oktober 1913 zahlte 1,5 Millionen Reichsmark, während Preußen © Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R15350 / CC-BY-SA das Grundstück zur Verfügung stellte. -

Knut Døscher Master.Pdf (1.728Mb)

Knut Kristian Langva Døscher German Reprisals in Norway During the Second World War Master’s thesis in Historie Supervisor: Jonas Scherner Trondheim, May 2017 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Preface and acknowledgements The process for finding the topic I wanted to write about for my master's thesis was a long one. It began with narrowing down my wide field of interests to the Norwegian resistance movement. This was done through several discussions with professors at the historical institute of NTNU. Via further discussions with Frode Færøy, associate professor at The Norwegian Home Front Museum, I got it narrowed down to reprisals, and the cases and questions this thesis tackles. First, I would like to thank my supervisor, Jonas Scherner, for his guidance throughout the process of writing my thesis. I wish also to thank Frode Færøy, Ivar Kraglund and the other helpful people at the Norwegian Home Front Museum for their help in seeking out previous research and sources, and providing opportunity to discuss my findings. I would like to thank my mother, Gunvor, for her good help in reading through the thesis, helping me spot repetitions, and providing a helpful discussion partner. Thanks go also to my girlfriend, Sigrid, for being supportive during the entire process, and especially towards the end. I would also like to thank her for her help with form and syntax. I would like to thank Joachim Rønneberg, for helping me establish the source of some of the information regarding the aftermath of the heavy water raid. I also thank Berit Nøkleby for her help with making sense of some contradictory claims by various sources. -

The Historic Dahlem District and the Fritz-Haber-Institut

Sketch of the south-west border of Berlin today Berlin 1885 1908 Starting with a comparison of sciences in Prussia with that in France, England, and USA, Adolf von Harnack (a protestant theologian) suggested to the Kaiser to found research institutes named "Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes for Scientific Research". The Kaiser liked the idea and was fully supportive: 1910 "... We need institutions that exceed the boundaries of the universities and are unimpaired by the objectives of education, but in close association with academia and universities, serving only the purpose of research ... it is my desire to establish under my protectorate and under my name a society whose task it is to establish and maintain such institutes .... 1911 Foundation of the "KWI for Chemistry" and the "KWI for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry" (first director: Fritz Haber) -- about 10 more institutes were founded during the coming 10 years. 1 1912 Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry and for Physical- Chemistry and Electrochemistry -- Most right: Villa of Fritz Haber. Kaiser Wilhelm II, Adolf von Harnack, followed by Emil Fischer and Fritz Haber walking to the opening cere- mony of the first two KWG institutes October 1912 Arial view of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes for "Chemistry" and for "Physical-Chemistry and Electrochemistry" -- around 1918 2 A glimpse at the history of the Fritz-Haber- Institute of the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1911 Foundation of the Kaiser- Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electro- chemistry (first director: Fritz Haber) 1914 Research and production -1918 of chemical weapons (mustard gas, etc.) 1918 Haber received the Nobelprize for the development of the ammonia synthesis Fritz Haber and 1933 Haber leaves Germany Albert Einstein at (see also FHI- webpages: history and the "FHI" -- 1915 2 brief PBS reports.) A glimpse at the history of the Fritz-Haber- Institute of the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft 1911 Foundation of the Kaiser-Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry (1. -

2018 • Vol. 2 • No. 2

THE JOURNAL OF REGIONAL HISTORY The world of the historian: ‘The 70th anniversary of Boris Petelin’ Online scientific journal 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 Cherepovets 2018 Publication: 2018 Vol. 2 No. 2 JUNE. Issued four times a year. FOUNDER: Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education ‘Cherepovets State University’ The mass media registration certificate is issued by the Federal Service for Supervi- sion of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor). Эл №ФС77-70013 dated 31.05.2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: O.Y. Solodyankina, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) DEPUTY EDITORS-IN-CHIEF: A.N. Egorov, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) E.A. Markov, Doctor of Political Sciences (Cherepovets State University) B.V. Petelin, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Cherepovets State University) A.L. Kuzminykh, Doctor of Historical Sciences (Vologda Institute of Law and Economics, Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia) EDITOR: N.G. MELNIKOVA COMPUTER DESIGN LAYOUT: M.N. AVDYUKHOVA EXECUTIVE EDITOR: N.A. TIKHOMIROVA (8202) 51-72-40 PROOFREADER (ENGLISH): N. KONEVA, PhD, MITI, DPSI, SFHEA (King’s College London, UK) Address of the publisher, editorial office and printing-office: 162600 Russia, Vologda region, Cherepovets, Prospekt Lunacharskogo, 5. OPEN PRICE ISSN 2587-8352 Online media 12 standard published sheets Publication: 15.06.2018 © Federal State Budgetary Educational 1 Format 60 84 /8. Institution of Higher Education Font style Times. ‘Cherepovets State University’, 2018 Contents Strelets М. B.V. Petelin: Scientist, educator and citizen ............................................ 4 RESEARCH Evdokimova Т. Walter Rathenau – a man ahead of time ............................................ 14 Ermakov A. ‘A blood czar of Franconia’: Gauleiter Julius Streicher ...................... -

Otto Hahn Medal 2015

Outstanding! Junior scientists of the Max Planck Society June 2016, Saarbrücken Contents Foreword ......................... 2 The Otto Hahn Medal .......... 4 – 35 The Otto Hahn Award .............36 The Dieter Rampacher Prize .......40 The Nobel Laureate Fellowship ....42 The Reimar Lüst Fellowship ........48 Impressum ......................49 1 Outstanding! The Max Planck Society is always on the lookout for the most creative, innovative minds in almost every discipline of the basic sciences. We offer such pioneers ideal conditions for the achieve ment of their research goals. From the Directors to our doctoral students, Max Planck researchers of all career stages have the courage and intellec tual strength to open up new chapters in science. Especially in the case of junior scientists, our aim is to make them more aware of their own abilities and to encourage them to find their own way in research. Support of junior scientists is there fore an essential element of the Max Planck Society. We are fully aware that the same universal law holds true in science as elsewhere: the future depends on the upandcoming generation! The level at which our junior scientists pursue their research is consistently high across all 83 Institutes. Nevertheless, every year we single out a small number of junior scientists whose achievements we deem to be particularly out standing. They have succeeded – right at the start of their careers – in demonstrating a high degree of scientific creativity. The laureates featured in this booklet will be honoured at a ceremony at the 2016 Annual General Meeting in Saarbrücken in the presence of all the members of the Max Planck Society. -

Gilbert Molinier Lorsqu'alain Badiou Se Fait Historien : Heidegger, La

Texto ! Textes et cultures, vol. XXIV, n°3 (2019) Gilbert Molinier Lorsqu’Alain Badiou se fait historien : Heidegger, la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, et coetera « [L]e spectacle que m’a offert l’université a contribué à m’exorciser complètement, à me délivrer d’une catharsis qui s’est achevée à la Sorbonne quand j’ai vu mes collègues, tous ces singes qui lisaient Heidegger et le citaient en allemand. »1 Vladimir Jankélévitch Résumé. — Cette étude traite d’une dénégation collective. Situant ses recherches au niveau et dans la lignée des prestigieux penseurs de la question de l’Être, Parménide, Aristote, Malebranche…, Alain Badiou rencontre Martin Heidegger. Or, celui-ci est soupçonné d’avoir été et/ou d’avoir toujours été un nazi inconditionnel. Souhaitant effacer une telle tache, Alain Badiou affirme, d’une part : « [Il] n’y a absolument pas besoin de chercher dans sa philosophie des preuves qu’il était nazi, puisqu’il était nazi, voilà ! […] » ; d’autre part et en même temps, il infirme : « C’est bien plutôt dans ce qu’il a fait, ce qu’il a dit, etc. » Cet « etc. » contient donc « ce qu’il a pensé, ce qu’il a écrit » . C’est sur une telle dénégation collective que s’appuient encore l’enseignement et la recherche universitaires dans de nombreux pays, en particulier en France. Or, une dénégation si marquée ne va pas sans produire des effets négatifs. Resümee. — Ursprung der folgenden Bemerkungen ist eine kollektive Verneinung. Alain Badiou, der es liebt, seine Forschungen auf die Ebene und in Übereinstimmung mit den angesehenen Denkern zur Frage des Seins, Parménides, Aristoteles, Malebranche… zu stellen, trifft einen gewissen Martin Heidegger. -

Außenpolitik, Öffentlichkeit, Öffentliche Meinung Deutsche Streitfälle in Den „Langen 1960Er Jahren“ Vo N Peter Hoeres

Außenpolitik, Öffentlichkeit, öffentliche Meinung Deutsche Streitfälle in den „langen 1960er Jahren“ Vo n Peter Hoeres Am 17. März 1966 legte der Leiter des Pressereferats Hans Jörg Kastl sei- nem Dienstherrn, Außenminister Gerhard Schröder, einen Vermerk über ein Gespräch zwischen Axel Springer und Ludwig Erhard vor: „Axel Springer habe im Verlauf dieses Gesprächs geäußert, er werde die Politik des Herrn Bundeskanzlers solange nicht unterstützen, wie Dr. Schröder Bundesaußenminister sei. Der Bundeskanzler habe geantwortet, dann müs- se er eben auf die Unterstützung des Springer-Konzerns verzichten.“1 Der angeblich so mächtige Medienzar konnte seine Personalvorstellun- gen also selbst bei „Ludwig, dem Kind“, wie der weiche Erhard in Adenau- ers Umgebung genannt wurde2, nicht ansatzweise zur Geltung bringen. Er hatte es aber in aller Deutlichkeit versucht, sogar mit diesem offenen Junk- tim. Man könnte viele weitere Beispiele für die versuchte Steuerung der Politik durch die Medien aus dieser Zeit anführen, bekannt ist Rudolf Aug- steins Maxime, Strauß dürfe es niemals ins Kanzleramt schaffen.3 Die Politiker waren aber nicht nur tatsächliche oder vermeintliche Opfer anmaßender Großpublizisten. Sie spielten das Spiel auch mit, und zwar nicht nur Adenauer, der es mit seiner „Off the Record“-Technik schaffte, in- und ausländische Journalisten ungefragt zu Verbündeten zu machen.4 Trotz der Schröder-Feindschaft des Springer-Verlages hielt auch der Au- 1 Vermerk Kastl 17.3.1966, in: Archiv für Christlich-Demokratische Politik (ACDP), 01–483/214–1. 2 Vgl. Franz Josef Strauß, Die Erinnerungen. Berlin 1989, 414. 3 Vgl. Rudolf Augstein über Franz Josef Strauß in seiner Zeit, in: Der Spiegel 10.10.1988, 18–27. -

One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research

Bretislav Friedrich · Dieter Hoffmann Jürgen Renn · Florian Schmaltz · Martin Wolf Editors One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences Bretislav Friedrich • Dieter Hoffmann Jürgen Renn • Florian Schmaltz Martin Wolf Editors One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare: Research, Deployment, Consequences Editors Bretislav Friedrich Florian Schmaltz Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Max Planck Institute for the History of Society Science Berlin Berlin Germany Germany Dieter Hoffmann Martin Wolf Max Planck Institute for the History of Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Science Society Berlin Berlin Germany Germany Jürgen Renn Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Berlin Germany ISBN 978-3-319-51663-9 ISBN 978-3-319-51664-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-51664-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017941064 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncom- mercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. -

James, Steinhauser, Hoffmann, Friedrich One Hundred Years at The

James, Steinhauser, Hoffmann, Friedrich One Hundred Years at the Intersection of Chemistry and Physics Published under the auspices of the Board of Directors of the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society: Hans-Joachim Freund Gerard Meijer Matthias Scheffler Robert Schlögl Martin Wolf Jeremiah James · Thomas Steinhauser · Dieter Hoffmann · Bretislav Friedrich One Hundred Years at the Intersection of Chemistry and Physics The Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society 1911–2011 De Gruyter An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Aut ho rs: Dr. Jeremiah James Prof. Dr. Dieter Hoffmann Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Institute for the Max Planck Society History of Science Faradayweg 4–6 Boltzmannstr. 22 14195 Berlin 14195 Berlin [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Thomas Steinhauser Prof. Dr. Bretislav Friedrich Fritz Haber Institute of the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society Max Planck Society Faradayweg 4–6 Faradayweg 4–6 14195 Berlin 14195 Berlin [email protected] [email protected] Cover images: Front cover: Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry, 1913. From left to right, “factory” building, main building, director’s villa, known today as Haber Villa. Back cover: Campus of the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society, 2011. The Institute’s his- toric buildings, contiguous with the “Röntgenbau” on their right, house the Departments of Physical Chemistry and Molecular Physics. -

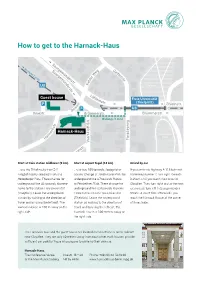

How to Get to the Harnack-Haus

How to get to the Harnack-Haus ............................................ ............................................ ............................................ ............................................ t ............................................ Saargemünderstr. ............................................ t ............................................ Krumme Lanke ............................................ S g G ............................................ a e e ............................................ a lfe ............................................ rg W r ............................................ e r ts ............................................ m le t ............................................ ü r. ............................................ n h ............................................ d e ............................................ e K ............................................Thielpark U3 r ............................................ s ............................................ t ............................................ r. ............................................ q ............................................ L ............................................ ö ............................................ Guest house hle Freie............................................ Universität ins ............................................ tr. ............................................(Thielplatz) P tr ............................................Löhleinstr. s t ............................................t -

Verlag C. H. Beck München Mit 22 Abbildungen

Verlag C. H. Beck München Mit 22 Abbildungen Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Hach meist er, Lutz: Der Gegnerforscher: die Karriere des SS-Führers Franz Alfred Six / Lutz Hachmeister. – München: Beck, 1998 ISBN 3-406-43507-6 ISBN 3 406 43507 6 © C. H. Beck’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Oscar Beck), München 1998 Satz: Janss, Pfungstadt. Druck und Bindung: Ebner, Ulm Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (Hergestellt aus chlorfrei gebleichtem Zellstoff) Printed in Germany Eingescannt mit OCR-Software ABBYY Fine Reader Inhalt I. Vorbemerkung ........................................................................... 7 II. «Durch Tod erledigt» Das «Einsatzkommando Österreich»: Wien 1938 ................................................................................... 10 III. «Als gäb’ es nichts Gemeines auf der Welt» Die Studentenzeit des Gegnerforschers: Heidelberg 1930-1934................................................................. 38 IV. «Abends Zusammensein im ,Bhitgericht‘» Von der Zeitungskunde zur politischen Geistesgeschichte: Königsberg und Berlin 1934-1940 ............................................. 77 V. «Der Todfeind aller rassisch gesunden Völker» Franz Alfred Six im SD-Hauptamt: Berlin 1933-1939 144 VI. «Möglichst als Erster in Moskau» Von der Gründung des RSHA bis zum «Osteinsatz»: 1939-1941 .................................................................................. 199 VII. «Ad majorem Sixi gloriam» Im Auswärtigen Amt: 1942-1943 239 VIII. «In a state of chronic tension» Die Verhöre -

Drama Around a War-Time Heisenberg Letter

Stephan Schwarz 12 April 2016 Drama around a war-time Heisenberg letter Abstract Das Ideal lässt sich am besten A recently published 1943 Heisenberg letter has been interpreted as an den Opfern messen, die es verlangt. reporting on a sudden chasm in a close relation between Heisenberg and (Ascribed to C.F.v. Weizsäcker; Carl Friedrich v. Weizsäcker. With reference to other sources concerning Untranslatable since ”Opfer” can the relations and attitudes of these protagonists it is argued that there was mean either sacrifices or victims) from the beginning an imbalance and lack of congruence in important ways, persisting over time, the 1943 incident rather being an atypical expression of frustration, with little repercussion on the relationship. This letter can even be interpreted as a unique expression of its author’s resentment of phraseology with roots in Nazi rhetoric. Keywords: Heisenberg, Weizsäcker, Heidegger, relations, National Socialist rhetoric 1. Heisenberg’s version 1 In a letter to his wife Elisabeth, called ”Li”(14 October 1943; Hirsch-Heisenberg, 2011, p.224), who had moved with the children to the family’s secondary residence in the Bavarian Alps, Werner Heisenberg (WH) reports on ”a long conversation” the evening before with his friend and former protégé Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker (CFvW). A section of this letter (which is reproduced here in extenso as Appendix) has recently been given an interpretation as evidence of a dramatic rupture of a presumably close friendship: In these days, there are ubiquitous arguments over wartime efforts. Carl Friedrich v. Weizsäcker [CFvW was, since a year, full professor of Theoretical Physics at the Kamfuniversität in Strasbourg] is here Elisabeth o.