Sacred Text References: Reflection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Vegetarianism’ Is a Case for Returning to Our Essence As Beings Created in the Image and Likeness of God

“This important pamphlet helps us advance the supreme Jewish goals of tikkun olam (healing and improving our world) and kiddush haShem (sanctifying the Divine Name).” —RABBI DAVID ROSEN, FORMER CHIEF RABBI OF IRELAND “The authors have powerfully united scientific and spiritual perspectives on why we—as Jews, as human beings, and as members of the global commons—should ‘go vegetarian.’” —RABBI FRED SCHERLINDER DOBB, COALITION ON THE ENVIRONMENT AND JEWISH LIFE A CASE FOR ‘“A Case for Jewish Vegetarianism’ is a case for returning to our essence as beings created in the image and likeness of God. It is a guide to be ... read and a guideline to be followed.” —RABBI RAMI M. SHAPIRO, SIMPLY JEWISH AND ONE RIVER FOUNDATION EWISH “Judaism … inspires and compels us to think before we eat. ‘A Case for J Jewish Vegetarianism’ provides many powerful reasons for us to be even VEGETARIANISM more compassionate through the foods we choose to consume.” —RABBI JONATHAN K. CRANE, HARVARD HILLEL “The case for Jewish vegetarianism is increasingly compelling, for ethical, environmental and health reasons--this provocative and important booklet makes that case lucidly from all three perspectives.” —RABBI BARRY SCHWARTZ, CENTRAL CONFERENCE OF AMERICAN RABBIS TASK FORCE ON KASHRUT FOR ANIMALS, FOR YOURSELF, AND FOR THE ENVIRONMENT People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals • GoVeg.com VEG314 1/05 RABBINIC STATEMENTS OF SUPPORT INTRODUCTION The Variety of Jewish Arguments for Vegetarianism “In contemporary society, more than ever before, vegetarianism should be an imperative Vegetarianism is becoming more and more popular in North for Jews who seek to live in accordance with Judaism’s most sublime teachings. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations. -

The Papers of Roberta Kalechofsky

BROOKLYN COLLEGE LIBRARY ARCHIVES & SPECIAL COLLECTIONS 2900 BEDFORD AVENUE BROOKLYN NEW YORK 11210 718 951 5346 http://library.brooklyn.cuny.edu THE PAPERS OF ROBERTA KALECHOFSKY Accession #2010-003 Dates Inclusive dates: 1950s-1970s Bulk dates: 1960s-1970s Extent 3 boxes / 1½ cubic feet Creator Roberta Kalechofsky Access/Use This collection is open for research. Copyright is retained by Dr. Kalechofsky. Materials can be accessed at the Brooklyn College Library Archive, 2900 Bedford Avenue (Room 130), Brooklyn, New York. Languages English Finding Aid Guide is presently available in-house and online. Acquisition/ Appraisal Collection was donated to the college archive by Dr. Kalechofsky in 2010. Description Control Finding aid content adheres to that prescribed by Describing Archives: A Content Standard. Collection was processed by Edythe Rosenblatt. Preferred Citation Item, folder title, box number, The Papers of Roberta Kalechofsky, Brooklyn College Archives & Special Collections, Brooklyn College Library Subject Headings Kalechofsky, Roberta. Satire, English – History and criticism. Dystopias in literature. Jews–Latin America. Latin American literature – Jewish authors – Translations into English. Jewish literature – Women authors. Jewish women – Literary collections. Jewish women – Biography. Women and literature. Australian literature – Jewish authors. th Australian literature – 20 century. New Zealand literature – Jewish authors. th New Zealand literature – 20 century. Jews – Australia – Literary collections. Jews – New Zealand – Literary collections. Vegetarianism – Religious aspects – Judaism. Jewish ethics. Animal welfare – Religious aspects – Judaism. Animal welfare (Jewish law). Animal rights – Religious aspects – Judaism. Biographical Note Roberta Kalechofsky, (1931- ), was born and raised in Brooklyn and received her undergraduate degree from Brooklyn College (1952). She earned her master’s in 1956 and her Ph.D. -

Democracy, Dialogue, and the Animal Welfare Act

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Michigan School of Law University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 51 2018 Beyond Rights and Welfare: Democracy, Dialogue, and the Animal Welfare Act Jessica Eisen Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Animal Law Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Jessica Eisen, Beyond Rights and Welfare: Democracy, Dialogue, and the Animal Welfare Act, 51 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 469 (2018). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol51/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND RIGHTS AND WELFARE: DEMOCRACY, DIALOGUE, AND THE ANIMAL WELFARE ACT Jessica Eisen* ABSTRACT The primary frameworks through which scholars have conceptualized legal pro- tections for animals—animal “rights” and animal “welfare”—do not account for socio-legal transformation or democratic dialogue as central dynamics of animal law. The animal “rights” approach focuses on the need for limits or boundaries preventing animal use, while the animal “welfare” approach advocates balancing harm to animals against human benefits from animal use. Both approaches rely on abstract accounts of the characteristics animals are thought to share with humans and the legal protections they are owed as a result of those traits. -

Those Hardy Vegetarians Their Ucculent Cuisine

The Journal of the Association of Adventist Forums Those Hardy Vegetarians Their ucculent Cuisine HARVARD PROFESSOR APPLAUDS POSITIVE VEGETARIANISM MOST VEGETARIANS LIVE SIX YEARS LONGER (AT LEAST} BEST OF THE VEGETARIAN COOKBOOKS SHORT STORY: SDAs IN CHIAPAS, MEXICO PURGES AT WALLA WALLA? e Aamodt® 1997 Commission • Patzer e Watts SCRIVEN, PIPIM DEBATE FUNDAMENTALISM September 1997 Volume 26, Number 3 Spectrum Editorial Board Consulting Editors Editor Beverly Beem Karen Bottomley Edna May• Lovel..,. English, Chair History English Roy Branson Walla Walla College Canadian Union College La Sierra University Bonnie L. y Edward Lugenbeal Roy Benton c ... Anthropology Malbematical Sciences Writer/Editor Atlantic Union College Senior Editor Columbia Union_ College Washington, D.C Donald R. McAdamo TomDybdahl Roy Branson Raymond Cottrell President Etbics, Kennedy Institute Tbeology McAdams, Faillace, and Assoc. Georgetown University Lorna linda, California ClarkDavlo Ronald Numbers Assistant Editor Joy c-ano Coleman History of Medicine Fteelance Writer History Chip Cassano University of Wisconsin Federalsburg, Maryland La Sierra University Lawrence Geraty Benjamin Reaves MolleurUiii Couperus President P!Jysiclan President Book Review Editor Oakwood College St. Helena, California La Sierra University Gary Chartier Fritz Guy Gerhard Svrcek..Seiler Gene Daffern Psychiatrist P!Jysiclan Tbeology Vienna, Austria Frederick, Maryland La Sierra University Production Helen Ward Thomp&On Bonnie Dwyer Karl Hall Educational Administration Journalism Doctoral -

ROBERTA KALECHOFSKY Lslims and W03)

:inctfrom s. Rather, .ecially in mmunion Hierarchy, Kinship, and Responsibility The Jewish Relationship to The Animal World tHer in the ROBERTA KALECHOFSKY lslims and W03). P·59· lAnswers" ce of Ani liatry and Its, p. 30!. oss to Ani o. imals," in Under the biblical perspective, a change took of law. Like any body of law, these decisions place in the status ofanimals from what had pre rest on precedent and authoritative statements, als," p. 32. vailed in Babylonian and Egyptian cultures: ani in this case by rabbis in the Talmud, or by rab ifo in Jew mals were demythologized-as were humans. bis throughout the centuries whose decisions are NewYork: There are no animal deities in the Bible; there called "responsa." However strong the aggadic are no human deities in the Bible. Animal life tradition might be on any issue, halachic deci .-Sherbok, was neither elevated nor degraded because of sions take precedent in governing the behavior {Theology the demythologizing process. Animals were no of the observant Jew, though they do not always longer worshipped, singly or collectively, but express the underlying ethos of the tradition. they were accorded an irreducible value in the As in any culture, sentiment is often stronger divine pathos, which is expressed in the cove than law. nantal statements, in halachic decisions or laws, The biblical and Talmudic position with re and in aggadic materiaL These three branches spect to animals is summarized in the statement of Jewish expression determine the tradition by Noah Cohen: known in Judaism as tsa'ar ba'alei chaim (cause no sorrow to living creatures). -

Animal Justice and Moral Mendacity∗ by Purushottama Bilimoria

Pacific Coast Theological Society Spring 2016 Animal Justice and Moral Mendacity∗ by Purushottama Bilimoria Introduction There is always the risk of romanticization when it comes to tackling the topic of animals, in classical discourses to contemporary practices. There are numerous issues to consider where animals are depicted and represented, or misrepresented. These may pertain to human sacrifice of animals, symbolic imagery in high-order astral practices, mythic and hybrid iconography in ancient mythologies, art and religions. We might next mention the depiction of animals as the denizens of monstrous evil, as threatening part of ‘brutish nature’, living out the law of the jungle, and hence requiring to be subdued under the law of the survival of the fittest. Huge dinosaurs, mammoths and other ‘monsters’ (think of "Jaw", "Armageddon", "Avatar", etc) are reconstructed (often digitally) or virtually resurrected from fossils and archeological excavations, with a certain degree of imaginative extrapolation, albeit without theoretical sophistication, which end up being projected on large cinemascope screens. Then there is the utilitarian deployment of animals in agro- culture, farming – the importance of the poultry, bovine, sea-and- water creatures, and a variety of other animal species ("delicacies") in dietary praxis and food consumption (meat industry, factory farming); but also in game hunting; the circus and the zoo, domestic pet culture; animal guide (for the challenged human); veterinarian vivisection; animal exhibitions (at annual shows and sale-yards, as once the practice with slaves in this country); not to mention beastiality and ∗ A version of this paper appeared in the e-journal : Berkeley Journal for Religion and Theology, vol 1 no 1, 2015: 56-79. -

JVS Mag No.164 – March 2008

The Jewish Vegetarian Wishing all members a Happy and Kosher Pesach TAN HOON SIANG MIST HOUSE – SINGAPORE © Dean & Tom No. 164 March 2008 Adar 5768 £1.50 Quarterly “...They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain” (Isaiah) The Official Journal of the Jewish Vegetarian and Ecological Society Founded by Philip L. Pick. Registered Charity No. 258581 (Affiliated to the International Vegetarian Union) Administrative Headquarters: 853/855 Finchley Road, London NW11 8LX, England. Tel: 020 8455 0692 Fax: 020 8455 1465 E-mail: [email protected] Committee Chairperson: Honorary Secretary: Shirley Labelda Honorary Treasurer: Michael Freedman FCA Honorary Auditors: Michael Scott & Co. ISRAEL Honorary President: Rabbi David Rosen Honorary Solicitors: Shine, Hunter, Martin & Co. 119 Rothschild Boulevard, 65271, Tel Aviv. The Jerusalem Centre: Rehov Balfour 8, Jerusalem 92102, Israel Tel/Fax: 1114. Email: [email protected] Friendship House (Orr Shalom Children’s Homes Ltd): Beit Nekofa, POB 80, DN Safon Yehuda 90830. Tel: (972)2 5337059 ext 112. www.orr-shalom.org.il AUSTRALASIA Honorary President: Stanley Rubens, LL.B. Convener: Dr Myer Samra Victoria Secretary: Stanley Rubens. 12/225 Orrong Road, East St Kilda. Vic 3183. THE AMERICAS Honorary President: Prof. Richard Schwartz Ph.D. (Representation in most Western Countries) PATRONS Rabbi Raymond Apple (Israel); Mordechai Ben Porat (Israel); Chief Rabbi Shear Yashuv Cohen (Israel); Rabbanit Goren (Israel); Prof. Alex Hershaft (Israel); Dr. Michael Klaper (USA); Prof. Richard -

Peoples-Theology-In-Asia-Final.Pdf

M. Amaladoss, S.J. MICHAEL AMALADOSS, S.J. (1936-PRESENT) A Publication of the Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacic (JCAP) Fr. Amaladoss is a world-renowned Asian theologian from Tamil Nadu, South India. He has a Ph.D. from the Catholic Institute, Paris. He has taught theology at Vidyajyoti College of eology in Delhi and has been a visiting lecturer in Asia, Europe, and America. He is the author of 35 books and nearly 500 articles in theology, some of which have been translated into other languages. PEOPLES’ THEOLOGY IN ASIA eology is our search for a better understanding of our faith in relation to our lives. It Collection of the Lectures: PEOPLES’ THEOLOGY IN ASIA PEOPLES’ THEOLOGY is encountering God in the way God challenges our lives and our relationships. is is East Asia eological Encounter Program (2006-2018) aected by the historical, geographical, cultural, and religious circumstances in which we live. For those of us living in Asia, our situation will aect our experience of God and the way we speak about it. is is Asian theology. is book is an attempt to share my reections and provoke your own thinking! Michael Amaladoss, S.J. Michael Amaladoss, S.J JCAP BUDDHIST STUDIES & DIALOGUE GROUP e Jesuit Conference of Asia Pacic (JCAP) promotes interreligious dialogue with two world religious traditions: Islam and Buddhism. Since 2010 the JCAP Buddhist Studies & Dialogue group has conducted yearly workshops in various nations in Asia to facilitate Buddhist-Christian dialogue with a holistic approach: academically, spiritually, and practically. In 2015, the group published its rst anthology entitled e Buddha & Jesus, which comprises sixteen articles, while a second publication is scheduled for 2021, with even more articles. -

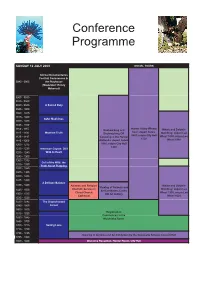

Conference Programme

Conference Programme SUNDAY 12 JULY 2009 SOCIAL TOURS Animal Documentaries Festival Commences in 0845 - 0900 the Playhouse (Moderator: Randy Malamud) 0900 - 0915 0915 - 0930 0930 - 0945 A Sacred Duty 0945 - 1000 1000 - 1015 1015 - 1030 Safer Medicines 1030 - 1045 1045 - 1100 1100-1115 Hunter Valley Winery Bushwalking and Whale and Dolphin Tour: depart hotels 1115 - 1130 Meat the Truth Birdwatching OR Watching: depart Lee 0845, return City Hall 1130 - 1145 Canoeing in the Hunter Wharf 1000, return Lee 1530 1145 - 1200 Wetlands: depart hotels Wharf 1300 1200 - 1215 0900, return City Hall 1430 1215 - 1230 American Coyote: Still 1230 - 1245 Wild At Heart 1245 - 1300 1300 - 1315 Cull of the Wild: the 1315 - 1330 Truth About Trapping 1330 - 1345 1345 - 1400 1400 - 1415 1415 - 1430 A Delicate Balance 1430 - 1445 Animals and Religion Whale and Dolphin Viewing of Animals and Interfaith Service in Watching: depart Lee 1445 - 1500 Art Exhibition, Cooks Christ Church Wharf 1330, return Lee 1500 - 1515 Hill Art Gallery Cathedral Wharf 1630 1515 - 1530 1530 - 1545 The Disenchanted 1545 - 1600 Forest 1600 - 1615 Registration 1615 - 1630 Commences in the 1630 - 1645 Mulubinba Room 1645 - 1700 1700 - 1715 Saving Luna 1715 - 1730 1730 - 1745 Viewing of Animals and Art Exhibition by the Newcastle School, Concert Hall 1745 - 1800 1800 - 1930 Welcome Reception, Hunter Room, City Hall MONDAY 13 JULY 2009 Banquet Room 0800 - 0900 Registration Concert Hall 0900 - 0905 Introductions: Rod Bennison and Jill Bough, Minding Animals Conference Co-convenors, Animals -

A Quaker Weekly

A Quaker Weekly VOLUME 4 NOVEMBER 15, 1958 NUMBER 41 IN THIS ISSUE ~air ~ P•n•trat•d by the brightness and heat of the The "Song of the Lord" sun, and iron is penetrated by by Gilbert Wright fire; so that it wor.ks through fire the works of fire, since it burns and shines like fire ..• yet each of these keeps its own. The Nurture of Preparative Meetings nature-the fire does not be by Robert 0. Blood, Jr. come iron, and the iron does not become fire, for the iron is within the fire and the fire within the iron, so likewise Where the Need for Understanding God is in the being of the soul. The creature never becomes Is Greatest God as God never becomes by Richard Taylor creature. -JAN VAN RUYSBROECK Letter from Japan by Jackson H. Bailey Conference of the Lake Erie Association FIFTEEN CENTS A COPY $4.50 A YEAR 658 FRIENDS JOURNAL November 15, 1958 Conference of the Lake Erie Association FRIENDS JOURNAL HE Lake Erie Association of Friends Meetings held its T nineteentll annual conference on August 22 to 24, 1958, at Friends Boarding School, near Barnesville, Ohio. The quiet peace of rolling hills and surrounding farmlands provided the setting_for the "soul searching and practical concerns" of the weekend gathering. J. Floyd Moore of the Religion Department of Guilford College spoke on tlle conference theme, "A Spiritual Ministry for Our Times." He emphasized the need for a life of prayer Published weekly, except during July and August when and worship, for keeping channels open when there is disagree published biweekly, at 1616 Cherry Street, Philadel ment, and for tlle practice of the personal ministry of love.