Manifestation of Latvian National Identity Through Contemporary Latvian Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

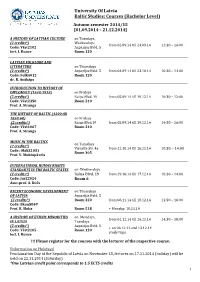

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Download Download

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 27–36 LIVONIAN LANDSCAPES IN THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF LIVONIA AND THE DIVISION OF THE LIVONIAN TRIBES Urmas Sutrop Institute of the Estonian Language, Tallinn, and the University of Tartu Abstract. There is no exact consensus on the division and sub-division of the former Livonian territories at the end of the ancient independence period in the 12th century. Even the question of the Coastal Livonians in Courland – were they an indigenous Livonian tribe or a replaced eastern Livonian tribe – remains unsolved. In this paper the anonymously published treatise on the historical geography of Livonia by Johann Christoph Schwartz (1792) will be analysed and compared with the historical modern views. There is an agreement on the division of the Eastern Livonian territories into four counties: Daugava, Gauja, Metsepole, and Idumea. Idumea had a mixed Livo- nian-Baltic population. There is no consensus on the parochial sub-division of these counties. Keywords: Johann Christoph Schwartz, historical geography, Livonian tribes, Livonians DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.02 1. Introduction It is commonly believed that Livonians (like Estonians) did not form either territorial or political unity at the end of the ancient independence period in the 12th century (see e.g. Koski 1997: 45). The first longer document where Livonians are described is the Livonian Chronicle (Heinrici Cronicon Lyvoniae) for the period 1180 to 1227 written by Henry of Livonia, an eyewitness of these events. Modern ideas on the division of Eastern Livonian peoples and territories go back to the cartographic work of Heinrich Laakmann, who divided Livonians into three territories – Daugava, Thoreida, and Metsepole; and added that there was a mixed Livonian-Baltic population at the end of the 12th century in Idumea (see the map Baltic Lands: population about 1200 AD and explanation to this map in Laakmann 1954). -

Personal Names and Denomination of Livonians in Early Written Sources

ESUKA – JEFUL 2014, 5–1: 13–26 PERSONAL NAMES AND DENOMINATION OF LIVONIANS IN EARLY WRITTEN SOURCES Enn Ernits Estonian University of Life Sciences Abstract. This paper presents the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; specifies their chronology; and analyses the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. If we consider the dating of the event, the earliest sources mentioning Livonians are Gesta Danorum and the Tale of Bygone Years (both 10th century), but both sources present rather dubious information: in the first the battle of Bråvalla itself or the date are dubious (6th, 8th or 10th century); in the latter we cannot be sure that the member of the Rus delegation was really a Livonian. If we consider the time of recording, the earliest sources are two rune inscriptions from Sweden (11th century), and the next is the list of neighbouring peoples of the Russians from the Tale of Bygone Years (12th century). The personal names Bicco and Ger referred in Gesta Danorum, and Либи Аръфастовъ in Tale of Bygone Years are very problematic. The first certain personal name of a Livonian is *Mustakka, *Mustukka or *Mustoikka (from Finnic *musta ‘black’) written in 1040–1050s on a strip of birch bark in Novgorod. Keywords: Livs, Finnic peoples, ethnonyms, anthroponyms, onomastics DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.01 1. Introduction This paper (1) seeks to present the timeline of ethnonyms denoting Livonians; (2) to specify their chronology; (3) and to analyse the names used for this ethnos and possible personal names. It is supple- mental to the paper by Mauno Koski on words denoting Livonians (Koski 2011). -

Kumulativna Medčasovna Datoteka CEEB 1-8

Evrobarometer Srednje in Vzhodne Evrope 1990-1997: Kumulativna medčasovna datoteka CEEB 1-8 Reif, Karlheinz ADP - IDNo: CEEB1_8 Izdajatelj: Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov URL: https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/opisi/ceeb1_8 E-pošta za kontakt: [email protected] Opis raziskave Osnovne informacije o raziskavi ADP - IDNo: CEEB1_8 Glavni avtor(ji): Reif, Karlheinz, European Comission, Brussels Ostali (strokovni) sodelavci: Cunningham, George Kuzma, Malgorzata Hersom, Louis Vantomme, Jacques Izdelava: ZA - Zentralarchiv für Empirische Sozialforschung, ZEUS - Zentrum für Europäische Umfrageanalysen und Studien (Berlin, Nemčija, Köln, Nemčija, Mannheim, Nemčija; 2004) Datum izdelave: 2004 Kraj izdelave: Berlin, Nemčija, Köln, Nemčija, Mannheim, Nemčija Uporaba računalniškega programa za izdelavo podatkov: ni podatka Finančna podpora: CEC - Komisija evropskih skupnosti - Commission of European Communities, Brusel Številka projekta: ni podatka Izdajatelj: ADP - Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov - Univerza v Ljubljani Od: Izročil: ZA - Zentralarchiv für Empirische Sozialforschung Datum: 2005-09-14 Raziskava je del serije: CEEB - Evrobarometer srednje in vzhodne Evrope Raziskava Evrobarometer v srednji in vzhodni Evropi (CEEB) se je izvajala med letoma 1990 in 1997 pod okriljem Evropske komisije. Vodila sta jo Karlheinz Reif (do 1995) in George Cunningham. Izvedena je bila osemkrat v več kot 20 državah vzhodne Evrope (seznam sodelujočih po posameznih letih http://www.gesis.org/en/data_service/eurobarometer/ceeb/countries.htm). Vsako leto jeseni so ponovno spremljali odnos ljudi v posameznih državah do ekonomskih in demokratičnih reform v njihovih državah in zavest o dogajanju v Evropski uniji. Raziskava je sorodna standardnemu Evrobarometru, ki poteka v polletnih obdobjih v državah članicah Evropske unije in se prav tako osredotoča na javno podporo EU in drugih tem, ki so tičejo Evrope nasploh. -

East Baltic Vikings - with Particular Consideration to the Ctrronians

East Baltic Vikings - with particular consideration to the Ctrronians Swedish Allies in the Saga World EAST BALTIC At the mythical battlefield of Bravellir (Sw. VIKINGS - WITH Bnl.vallama), Danes and the Swedes clashed in a PARTICULAR fight of epic dimensions. The over-aged Danish king Harald Hildetand finally lost his life, and CONSIDERA his nephew king Sigurdr hringr won Denmark TION TO THE for the Swedes. The story appears in a fragment CURONIANS of a Norse saga from around 1300. But since Sa xo Grammaticus tells it, the written tradition Nils Blornkvist must go back at least to the late 12th century. Wri ting in Latin he prefers to call it bellum Suetici, 'the Swedish war'. It's for several reasons ob vious that Saxo has built his text on a Norse text that must have been quite similar to the preser ved fragment. The battle of Bravellir- the Norse fragment claims - was noteworthy in ancient tales for having be en the greatest, the hardest and the most even and uncertain of the wars that had been fought in the Nordic countries.1 Both sources give long lists of the famous heroes that joined the two armies in a way that recalls the list of ships in Homer's Iliad. These champions are the knight errants of Germanic epics, to some degree rela ted with those of chansons de geste. They are pre sented with characteristic epithets and eponyms that point out their origins in a town, a tribe or a country. When summed up they communicate a geographic vision of the northern World in the 11 th and 12th centuries. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Thinking Through the Growth of the Fashion Design Industry in Kenya

AFRICA ISSN: 2524-1354 (Online), ISSN: 2519-7851 (Print) Africa Habitat Review Journal Volume 14 Issue 2 (July 2020) HABITAT http://uonjournals.uonbi.ac.ke/ojs/index.php/ahr REVIEW 14(2) (2020) Thinking Through the Growth of The Fashion Design Industry in Kenya * Lilac Osanjo Received on 1st May, 2020; Received in revised form 19th June, 2020; Accepted on 29th June, 2020. Abstract This research aimed at investigating the foundation and environment that surrounded the government directive to the public to wear African clothes every Friday. It sought to unearth information on the status of the fashion industry in Kenya. Data was collected from media reports, internet sources and available literature coupled with information from the Kenya Fashion Council, in which the author serves as a council member. The findings indicate that Kenya, does not have a strong indigenous textile production history and depends on fabric mainly from West Africa; designers used cultural, style, handcrafted finishes and natural fabrics in their fashion products; and, government, models, institutions and red carpet events are important to the industry growth. The failure of the Kenya national dress was due to several factors, including omission of the Maasai shuka. The Kenya Fashion Council is expected to mobilize resources necessary to develop a vibrant fashion industry. Keywords: Fashion designers, African fabric, Kenya national dress, Maasai shuka, Kenya Fashion Council. INTRODUCTION and European markets coupled with influx of In October 2019, the Kenya Government issued cheaper second hand clothes imports. It was seen a directive that all public officers wear African that an organized fashion industry would see garments every Friday. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

The Nineteenth Century (History of Costume and Fashion Volume 7)

A History of Fashion and Costume The Nineteenth Century Philip Steele The Nineteenth Century Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2005 Bailey Publishing Associates Ltd Steele, Philip, 1948– Produced for Facts On File by A history of fashion and costume. Bailey Publishing Associates Ltd The Nineteenth Century/Philip Steele 11a Woodlands p. cm. Hove BN3 6TJ Includes bibliographical references and index. Project Manager: Roberta Bailey ISBN 0-8160-5950-0 Editor:Alex Woolf 1. Clothing and dress—History— Text Designer: Simon Borrough 19th century. 2. Fashion—History— Artwork: Dave Burroughs, Peter Dennis, 19th century. Tony Morris GT595.S74 2005 Picture Research: Glass Onion Pictures 391/.009/034—dc 22 Consultant:Tara Maginnis, Ph.D. 2005049453 Associate Professor of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and creator of the website,The The publishers would like to thank Costumer's Manifesto (http://costumes.org/). the following for permission to use their pictures: Printed and bound in Hong Kong. Art Archive: 17 (bottom), 19, 21 (top), All rights reserved. No part of this book may 22, 23 (left), 24 (both), 27 (top), 28 be reproduced or utilized in any form or by (top), 35, 38, 39 (both), 40, 41 (both), any means, electronic or mechanical, including 43, 44, 47, 56 (bottom), 57. photocopying, recording, or by any information Bridgeman Art Library: 6 (left), 7, 9, 12, storage or retrieval systems, without permission 13, 16, 21 (bottom), 26 (top), 29, 30, 36, in writing from the publisher. For information 37, 42, 50, 52, 53, 55, 56 (top), 58. contact: Mary Evans Picture Library: 10, 32, 45. -

803 Black Markets, Foreign Clothing, Identity Construction In

Volumen 10, Número 1 Otoño, 2018 Black Markets, Foreign Clothing, Identity Construction in Contemporary Urban Cuba Introduction Cuba is a fascinating island on which to conduct anthropological studies, as its exceptional political and economic situation has an enormous impact on Cuban people’s life. Due to the unique character of Cuba’s socialist governmental structure and policies, as well as the economic embargo imposed by the United States on Cuba, in combination with the economic hardship Cubans faced (and still face) after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Many Cubans rely on remittances, gifts, and imported goods from abroad to fulfill their (basic) consumption needs. Nevertheless, a new generation of young Cubans seems to be paying more attention to obtaining consumer goods–such as fashionable clothes, shoes, and smartphones–from abroad. As black markets flourish on the island as a result of the tendencies stated above, it is worthwhile to study what kind of goods are wanted and available, how they are provided and obtained, by whom they are sold and bought, and with what objectives. Geographically, Cuba belongs to the world, but it does not economically and politically participate fully in it. In relation to globalization, I noticed while I was there that Cubans, especially young Cubans, imagine their island as participating in 803 Volumen 10, Número 1 Otoño, 2018 global economies and politics while concomitantly feeling fettered by the restrictions and limitations that the reality of their current socioeconomic organization presents. As Foucault (1967) described, “there is a certain kind of heterotopia which I would describe as that of crisis; it comprises privileged or sacred or forbidden places that are reserved for the individual who finds himself in a state of crisis with respect to the society or the environment in which he lives” (331).