Improving Consumer Protection in the Prepaid Calling Card Market Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Bank Foreign Travel Card Rate May Be Applied (For Example: Register After the Transaction Debit Date

Welcome to the State Bank Multi-Currency Foreign Travel Card FIND OUT HOW TO; USE YOUR CARD OVERSEAS RELOAD YOUR CARD MANAGE YOUR BUDGET AND MUCH MORE... USER GUIDE Welcome to your new State Bank Multi-Currency Foreign Travel Card MasterCard® The CHIP and PIN protected prepaid card Here are some easy to follow instructions on using your Card On possession of your Card - Reload your Card l Please sign on the back of your Card as soon as you get it, and memorise your Personal Identification Number (PIN) (please note that you cannot change the PIN - for a PIN reminder, you can call Card Services to access the automated PIN read back service, at any time). Disputed Transactions l Register your Card on ‘My Account’ at www.sbitravelcard.com, It is recommended that you check by following the instructions on the screen. Load up to four your transaction history and Card Currenciesb onto one easy-to-use Card, in whatever combination balance at least once a fortnight. suits you#. If you have any queries about 1 your State Bank Multi-Currency Please note: The Card may not be used in India, Nepal and Bhutan . Foreign Travel Card balance or If you are entitled to a refund for you notice a Card transaction How to use your State that you do not recognise, please Bank Multi-Currency goods or services purchased using the Card, or another credit for any notify the 24 hour Card Services Foreign Travel Card other reason, this will be made to Checking your balance team without undue delay, and in Just like a debit card, you can use the Card and a foreign exchange Simply go to ‘My Account’ at any event no later than 30 days your State Bank Foreign Travel Card rate may be applied (For example: www.sbitravelcard.com, register after the transaction debit date. -

Recommendation for a Tactile Identifier on Machine Readable Cards for Telecommunication Terminals

ETSI ETR 165 TECHNICAL January 1995 REPORT Source: ETSI TC-HF Reference: DTR/HF-02010 ICS: 33.020, 33.040.40 Key words: Telephone prepayment cards, ID-1 cards, machine readable cards, tactile identifier, blind people, visually impaired people, older people, People with Special Needs (PWSN) Human Factors (HF); Recommendation for a tactile identifier on machine readable cards for telecommunication terminals ETSI European Telecommunications Standards Institute ETSI Secretariat Postal address: F-06921 Sophia Antipolis CEDEX - FRANCE Office address: 650 Route des Lucioles - Sophia Antipolis - Valbonne - FRANCE X.400: c=fr, a=atlas, p=etsi, s=secretariat - Internet: [email protected] Tel.: +33 92 94 42 00 - Fax: +33 93 65 47 16 Copyright Notification: No part may be reproduced except as authorized by written permission. The copyright and the foregoing restriction extend to reproduction in all media. New presentation - see History box © European Telecommunications Standards Institute 1995. All rights reserved. Page 2 ETR 165: January 1995 Whilst every care has been taken in the preparation and publication of this document, errors in content, typographical or otherwise, may occur. If you have comments concerning its accuracy, please write to "ETSI Editing and Committee Support Dept." at the address shown on the title page. Page 3 ETR 165: January 1995 Contents Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction....................................................................................................................................................5 -

June 2020 Program Handbook

PROGRAM HANDBOOK ® STAND WITH ISRAEL. IN ISRAEL. June 2020 Thank you for making a commitment to help Israel by serving in the Volunteers for Israel® (VFI) program. You are about to have one of the most rewarding and memorable experiences of your life. We have developed this booklet to assist you while getting ready for your adventure and while you are in Israel. Take it with you. It’s packed with information and helpful suggestions that will be useful to you — but only if you read every page carefully NOW and refer to it later. If you wait until you are on the plane, it could be too late. If you have any questions that have not been answered by our brochures, interviewers, or this handbook, please let us know. Because program details may change, we suggest that you check www.vfi-usa.org from time to time for the most current information. IMPORTANT: Miri Sharon is SAR-EL’s Program Coordinator. Keep her cell phone number with you in Israel: 054-755-0137. Add it to your phone contact list. Also add the phone number(s) of your madrichim. Volunteers for Israel® is a registered trademark of Volunteers for Israel. ©Volunteers for Israel, 2010. Revised June 2020. TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUNTEERING ON AN IDF BASE .................................................. 2 Madrichim – (group leaders) ....................................................................... 2 Work .......................................................................................................... 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION ................................................................. -

Simcard Cloning and Crimes: a Critical Analysis

I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 LEX FORTI L E G A L J O U R N A L V O L - I I S S U E - V I A U G U S T 2 0 2 0 I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form by any means without prior written permission of Editor-in-chief of LexForti Legal Journal. The Editorial Team of LexForti Legal Journal holds the copyright to all articles contributed to this publication. The views expressed in this publication are purely personal opinions of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Editorial Team of LexForti. Though all efforts are made to ensure the accuracy and correctness of the information published, LexForti shall not be responsible for any errors caused due to oversight otherwise. I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 EDITORIAL BOARD E D I T O R I N C H I E F R O H I T P R A D H A N A D V O C A T E P R I M E D I S P U T E P H O N E - + 9 1 - 8 7 5 7 1 8 2 7 0 5 E M A I L - L E X . F O R T I I @ G M A I L . C O M E D I T O R I N C H I E F M S . -

Call Home Economy

C all HOME Economy – NOW INCLUDED ON Telefonkarte COMFORT Germany > africa, arabic countries, eastern europe, central asia, central and south america | Änderungen und Irrtümer vorbehalten SIMPLY DIAL 0800 33 00321, ENTER THE PIN HELPFUL FEATURES FOR FREQUENT USERS 9 AND CALL THE DESIRED NUMBER PIN-less dialing: dial the access number 0800 33 00321 and enter your PIN, then press Free access number – no dial-up fee and 1 . When you dial the access number again, you won’t have to reenter your PIN. Stand 07/201 Available via landline or mobile phone – no new SIM card required Just enter the number you wish to call. You’ll only be charged if the call is connected Speed dial: enter and 4 , followed by a one- or two-digit speed-dial number and the telephone number (including prefix) you want to match with this speed dial. Call Home Economy – the low-priced and fair way to make Once PIN-less dialing has been set up with 1 and speed dial with 4 you only international calls! need to dial 0800 33 00321 followed by the one- or two-digit speed-dial number to connect to the desired phone number (if calling from the phone you have chosen to set up the features). NUMBER OF MINUTES YOU’LL RECEIVE WITH TELEFONKARTE COMFORT (EXAMPLE: WITH 10 EURO BALANCE) › › › › › › › › Ägypten / Egypt 91 71 45 40 Gabun / Gabon 25 22 19 18 Afghanistan / Afghanistan 38 43 27 29 Gambia / Gambia 16 16 14 14 Albanien / Albania 59 22 35 18 Georgien / Georgia 43 28 29 21 Algerien / Algeria 11 18 10 15 Ghana / Ghana 37 25 26 20 Angola / Angola 117 86 51 44 Griechenland / -

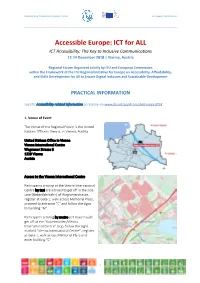

Accessible Europe: ICT for ALL ICT Accessibility: the Key to Inclusive Communications 12-14 December 2018 | Vienna, Austria

International Telecommunication Union European Commission Accessible Europe: ICT for ALL ICT Accessibility: The Key to Inclusive Communications 12-14 December 2018 | Vienna, Austria Regional Forum Organized Jointly by ITU and European Commission within the Framework of the ITU Regional Initiative for Europe on Accessibility, Affordability, and Skills Development for All to Ensure Digital Inclusion and Sustainable Development PRACTICAL INFORMATION Specific Accessibility related information accessible via www.itu.int/go/AccessibleEurope2018 1. Venue of Event The Venue of the Regional Forum is the United Nations Office in Vienna, in Vienna, Austria. United Nations Office in Vienna Vienna International Centre Wagramer Strasse 5 1220 Vienna Austria Access to the Vienna International Centre Participants arriving at the Vienna International Centre by taxi are advised to get off in the side lane (Nebenfahrbahn) of Wagramerstrasse, register at Gate 1, walk across Memorial Plaza, proceed to entrance “C” and follow the signs to building “M”. Participants arriving by metro (U1 line) should get off at the “Kaisermühlen/Vienna International Centre” stop, follow the signs marked “Vienna International Centre”, register at Gate 1, walk across Memorial Plaza and enter building “C”. 1 International Telecommunication Union European Commission There are no parking facilities for conference participants, except for Permanent Mission delegates in possession of a valid parking permit. 2. Registration Online registration prior to the event is strongly encouraged, and can be accessed via the event website www.itu.int/go/AccessibleEurope2018. Badge pickup and registration at the event venue starts Monday, 17 September 2018, at 8:30 a.m. and requires a valid national identity card. -

Handbook on New Technologies and New Services Has Been Prepared Taking Into Account These Two Statements of the Valletta Conference Held in 1998

*19165* Printed in Switzerland Geneva, 2001 ISBN 92-61-09291-8 q-16-2-fasc_2.indd 1 11.05.2001, 14:50 THE STUDY GROUPS OF THE ITU-D The ITU-D Study Groups were set up in accordance with Resolution 2 of World Telecommunication Development Conference (WTDC) held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1994. For the period 1998-2002, Study Group 1 is entrusted with the study of eleven Questions in the field of telecommunication development strategies and policies. Study Group 2 is entrusted with the study of seven Questions in the field of development and management of telecommunication services and networks. For this period, in order to respond as quickly as possible to the concerns of developing countries, instead of being approved during the WTDC, the output of each Question is published as and when it is ready. For further information Please contact: Ms. Fidélia AKPO Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) ITU Place des Nations CH-1211 GENEVA 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 5439 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 E-mail: [email protected] Placing orders for ITU publications Please note that orders cannot be taken over the telephone. They should be sent by fax or e-mail. ITU Sales Service Place des Nations CH-1211 GENEVA 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 6141 English Telephone: +41 22 730 6142 French Telephone: +41 22 730 6143 Spanish Fax: +41 22 730 5194 Telex: 421 000 uit ch Telegram: ITU GENEVE E-mail: [email protected] The Electronic Bookshop of ITU: www.itu.int/publications ITU 2001 All rights reserved. -

"Bezeq" the Israel Telecommunication Corp. Limited

"Bezeq" The Israel Telecommunication Corp. Limited Annual Report for 2006* Chapter A – Description of Company Operations Chapter B – Directors' Report on the State of the Company's Affairs Chapter C – Financial Statements Chapter D – Additional Details About the Corporation The information contained in this annual report constitutes a translation of the annual report published by the Company. The Hebrew version was submitted by the Company to the relevant authorities pursuant to Israeli law, and represents the binding version and the only one having legal effect. This translation was prepared for convenience purposes only. * The annual report was prepared in accordance with the Securities Regulations (Periodic and immediate reports), 5730-1970 Table of Contents Page Chapter A – Description of Company Operations 1. Description of General Development of Group Operations ............................ 1 1.1 Group Activity and Description of its Business Development ................................ 1 1.2 Areas of Operation ................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Investments in Equity and Stock Transactions ...................................................... 4 1.4 Payment of dividends............................................................................................. 5 1.5 Financial Information regarding the Group’s Areas of Operations......................... 7 1.6 General Environment and Effect of External Factors on Group Activity ................ 9 2. Fixed-Line -

Smart Card News Ltd., Brighton, England

DECEMBER 1997 6 Volume 12 Number British Govt Launches Smart Card Initiative The new Labour British government has formally legalised electronic signatures using a Smart Card and is therefore the first government to accept electronic forms from the general public over the Internet. The pilot scheme, which was launched by David Clark, Minister for Public Services, will be rolled out to thousands of people over the coming months and is the start of the governments commitment that a quarter of its business will be conducted electronically by the year 2002. The electronic form replaces a number of complex paper forms that were originally required to register as self employed. The form is on the Internet and is digitally signed using Smart Card technology provided by NatWest, the inventors of Mondex. Continued on page 223 Malaysian E-cash Project - See page 223 © 1997 Smart Card News Ltd., Brighton, England. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, optical, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. December 1997 News Cards on the Cover 223-235 Malaysian E-cash Project Natwest Signature Card Front Page Smart Cards for Fort Knox Manx Telecom Special Edition Christmas GCS Service Mark Plan Telephone Card US Postal Service Joins NY Pilot Page 232 Special Edition BT China Agrees EMV Standard Phonecard from a series called “The Fifth Age” Options Smart Credit Card for HK Page 240 Belgium Personalisation Centre GSM -

Functional Description ZVT POSEIDON

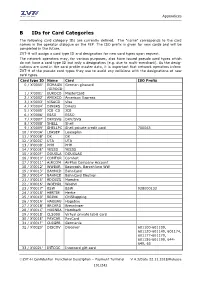

Appendices B IDs for Card Categories The following card category IDs are currently defined. The "name" corresponds to the card names in the operator dialogue on the FEP. The ISO prefix is given for new cards and will be completed in the future. ZVT-H will assign a card type ID and designation for new card types upon request. The network operators may, for various purposes, also have issued pseudo card types which do not have a card type ID but only a designation (e.g. due to multi-merchant). As the desig- nations are used in the card profile master data, it is important that network operators inform ZVT-H of the pseudo card types they use to avoid any collisions with the designations of new card types. Card type ID Name Card ISO Prefix 0 / X'0000' ECMAGN German girocard /GIROCD 1 / X'0001' EUROCD MasterCard 2 / X'0002' AMEXCO American Express 3 / X'0003' VISACD Visa 4 / X'0004' DINERS Diners 5 / X'0005' JCB_CD JCB 6 / X'0006' ESSO ESSO 7 / X'0007' DKVSVG DKV/SVG 8 / X'0008' SHELL Shell 9 / X'0009' SHELLPC Shell private credit card 700063 10 / X'000A' LEASEP Leaseplan 11 / X'000B' OK OK 12 / X'000C' UTA UTA 13 / X'000D' PHH PHH 14 / X'000E' YESSS YESSS 15 / X'000F' DOUGLA DOUGLAS 16 / X'0010' COMFOR Comfort 17 / X'0011' AIRCOM AirPlus Company Account 18 / X'0012' WWBAR Easycash, Barzahlung WW 19 / X'0013' BAHNCD BahnCard 20 / X'0014' BAHNCE BahnCard Electron 21 / X'0015' EDCGZS Maestro 22 / X'0016' WOEHRL Woehrl 23 / X'0017' BSW BSW 928000132 24 / X'0018' HERTIE Hertie 25 / X'0019' BRINK CitiShopping 26 / X'001A' HAGBAU Hagebau 27 / X'001B' -

Download Program Handbook

PROGRAM HANDBOOK With VFI, “You don’t just see Israel...you meet Israel.” — Louis Eisenhauer, New York Volunteer February 2019 Thank you for making a commitment to help Israel by serving in the Volunteers for Israel® (VFI) program. You are about to have one of the most rewarding and memorable experiences of your life. We have developed this booklet to assist you while getting ready for your adventure and while you are in Israel. Take it with you. It’s packed with information and helpful suggestions that will be useful to you — but only if you read every page carefully NOW and refer to it later. If you wait until you are on the plane, it could be too late. If you have any questions that have not been answered by our brochures, interviewers, or this handbook, please let us know. Because program details may change, we suggest that you check www.vfi-usa.org from time to time for the most current information. IMPORTANT: Miri Sharon is Sar-El’s Program Coordinator. Keep her cell phone number with you in Israel: 054-755-0137. Add it to your phone contact list. Also add the phone number(s) of your madrichim. Volunteers for Israel® is a registered trademark of Volunteers for Israel. ©Volunteers for Israel, 2010. Revised June 2019. TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUNTEERING ON AN IDF BASE .................................................. 2 Madrichim – (group leaders) ....................................................................... 2 Work .......................................................................................................... 3 PROGRAM -

COLLECTIONS and MIXED LOTS 1 Landis & Gyr Service Card No. 1 In

COLLECTIONS AND MIXED LOTS 1 Landis & Gyr service card No. 1 in arrows £0 2 Landis & Gyr service cards Nos. 2, 9 & 23 in arrows £0 3 Landis & Gyr service cards Nos 2, 14 & 23 in arrows £0 4 Landis & Gyr service card no. 22 in arrows Control 222G £0 5 Landis & Gyr service card No. 22 in arrows SODECO control 107H £0 EPHEMERA 6 British Telecom Dialling Codes plastic sign from phonebox £10 7 British Telecom "This payphone accepts only British Telecom Phonecards" sign from phonebox £10 8 BT 1991 "This payphone only accepts BT phonecards" plastic sign £8 9 BT Phonecard Clock Open/Closed sign for shop door 23.5 x 20.5 cm. £16 10 BT plastic dialling codes sign from phone box 1991 £8 ALASKA 11 1993 1st issue D1-D2 pair State Flag chip cards Mint. 2500 printed (2) £36 12 1993 Husky Sled Dog $3.50 Mint. 3000 printed £34 13 Husky Sled Dog Complimentary $3.50 Mint. 3000 printed £18 ALGERIA 14 L & G 10u green Mint £9 15 L & G 50u green Mint £12 AUSTRALIA 16 1995 Beijing Opera 2 x $5 & $20 mint (3) £9 17 Countrylink Train Series set of 3 (B) £8 18 Dance & Ballet Company pair mint £6 19 Donald & Mickey Disney pair (B) £6 20 History of Bass Strait Shipping set of 3 (B) £8 21 Hobart Electric Tramways set of 3 (B) £8 22 Lighthouses set of 3 (B) £9 23 Railways of Australia set of 3 (B) £8 24 The Gulflander pair (B) £6 25 The Overland passenger train service pair (B) £6 26 The Savannahlander Railways pair (B) £6 27 Victoria's Narrow gauge lines set of 3 (B) £7 28 West Coast Railways first set of 3 (B) £10 29 Wilderness Rivers set of 3 (B) £8 BAHRAIN 30 1986 1st issue D1-4 magnetic 25u, 50u, 100u & 200u used (4) £10 31 General Manager Andrew B.