OFT1158 Local Bus Services

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground

£5 when sold in paper format Available free by email upon application to: [email protected] An auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground Collectables Enamel signs & plates, maps, posters, badges, destination blinds, timetables, tickets & other relics th Saturday 25 February 2017 at 11.00 am (viewing from 9am) to be held at THE CROYDON PARK HOTEL (Windsor Suite) 7 Altyre Road, Croydon CR9 5AA (close to East Croydon rail and tram station) Live bidding online at www.the-saleroom.com (additional fee applies) TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Transport Auctions of London Ltd is hereinafter referred to as the Auctioneer and includes any person acting upon the Auctioneer's authority. 1. General Conditions of Sale a. All persons on the premises of, or at a venue hired or borrowed by, the Auctioneer are there at their own risk. b. Such persons shall have no claim against the Auctioneer in respect of any accident, injury or damage howsoever caused nor in respect of cancellation or postponement of the sale. c. The Auctioneer reserves the right of admission which will be by registration at the front desk. d. For security reasons, bags are not allowed in the viewing area and must be left at the front desk or cloakroom. e. Persons handling lots do so at their own risk and shall make good all loss or damage howsoever sustained, such estimate of cost to be assessed by the Auctioneer whose decision shall be final. 2. Catalogue a. The Auctioneer acts as agent only and shall not be responsible for any default on the part of a vendor or buyer. -

OFFICIAL TIMETABLE and MAP of BUS ROUTES - Summer Service, (First Issue)50 23/5/28''

LotNo Description Hammer 1 1928 East Surrey Traction Co Ltd ''OFFICIAL TIMETABLE AND MAP OF BUS ROUTES - Summer Service, (First Issue)50 23/5/28''. In good unmarked condition with some light wear and creasing to covers. [1] 2 London Transport fleetnumber BONNET PLATE and Registration NUMBER PLATE from AEC Regent RT 2906 (MLL80 653). The original bus with this number entered service at Alperton garage in 1952 and the final RT 2906 was withdrawn at Seven Kings garage in 1974, being scrapped the same year. Both plates are in ex-vehicle condition.[2] 3 London Underground ENAMEL ROUNDEL SIGN from King's Cross St Pancras Station. This is a medium-size sign950 measuring 51'' (131cm) across by 42'' (107cm) high, estimated to date from the 1980s/90s, and comes complete with brass frame. It has been mounted on board for display purposes. In excellent condition. [1] 4 Set of Green Line Coach leaflets bearing names of former independent companies comprising Route AW dated25 26-4-32 and 1-6-32 (both Bucks Expresses (Watford) Ltd), Route BG dated 5-8-32 (Skylark Motor Coach Co Ltd) and Route CF dated 24-8-32 (Regent Coach Service). All lightly used, the last has some stains. [4] 5 1930s LGOC/LPTB PANEL TIMETABLES comprising routes 79/115/620 (25-3-32), 494/194 (30.12.30), 113 (28.2.34),40 418/70B & 70D (25.4.34) and 81 (17-2-37). All with some wear/damage to varying degrees. [5] 6 London Transport 'Gibson' TICKET MACHINE no. 21391, a letter codes machine which appears to be in working250 order and prints a good ticket with 'London Transport' still on the plate. -

GEM's Date with Kate

Good motoringThe magazine for members of GEM Motoring Assist Autumn 2018 GEM’s date with Kate The TV presenter talks about her work, her driving... and her penchant for skinny dipping MOBILE PHONE FINES: HOW THE OTHER HALF DRIVE: COMPETITION: why are so many drivers bringing a few luxury touches win a two-night break still flouting the law? to life on the road in sunny Torquay 2008 2010 2011 2013 2014 2015 2017 2018 GOLD WINNER WINNERS AGAIN! THANKS FOR SUPPORTING US CONTENTS AUTUMN 2018 FEATURES 12 Your opportunity to win a wonderful two-night break for two people at classy On the cover Orestone Manor in south Devon. 14 Sharing the roads: Peter Rodger offers his thoughts on the value of stepping into another road user’s shoes, and Good Motoring editor James Luckhurst picks up some wise advice for staying safe on horseback. THESE ROADS WERE MADE FOR SHARING 20 GEM member survey: in this edition we What can drivers and riders do to ensure a safer road consider your opinions on car-buying and environment? Understanding each others’ needs - future mobility. 16 and respecting a horse’s brain - are key! 24 Speed enforcement: Neil Barrett lines up an array of cameras, cops and vans to understand why it’s done, and how effective devices are in reducing collisions. 28 At the wheel with Kate Humble: the TV On the cover presenter shares her thoughts on driving, skinny-dipping and why she wanted to be a professional gypsy. ADVENTURES 32 Western France and Atlantic Spain in the company of Rod Ashley. -

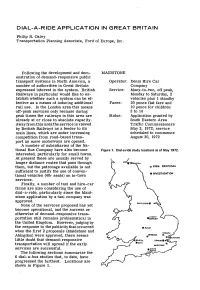

Dial-A-Ride Application in Great Britain

DIAL-A-RIDE APPLICATION IN GREAT BRITAIN Philip R. Oxley Transportation Planning Associate, Ford of Europe, Inc. Following the development and dem- MAIDSTONE onstration of demand-responsive public transport systems in North America, a Operator: Denis Hire Car number of authorities in Great Britain Company expressed interest in the system. British Service: Many-to-two, off peak, Railways in particular would like to es- Monday to Saturday, 2 tablish whether such a system can be ef- vehicles plus 1 standby fective as a means of inducing additional Fares: 20 pence flat fare and rail use. In the London area this means 10 pence for children off-peak services only because during 3 to 14 peak times the railways in this area are Status: Application granted by already at or close to absolute capacity. South Eastern Area Away from this areathe service is viewed Traffic Commissioners by British Railways as a feeder to its May 3, 1972; service main lines, which are under increasing scheduled to commence competition from road-based trans- August 30, 1972 port as more motorways are opened. A number of subsidiaries of the Na- tional Bus Company have also become Figure 1. Dial-a-ride study locations as of May 1972. interested, particularly for small towns. At present these are usually served by longer distance routes that pass through them, but the patronage available is not sufficient to justify the use of conven- S INVESTIGATIONPROPOSAL tional vehicles (40+ seats) on in-town services. Finally, a number of taxi and hire-car firms are also considering the use of dial-a-ride, particularly since the Maid- stone application by a taxi company was approved. -

Acu Handbook £8.00 2015

ACU HANDBOOK HANDBOOK ACU £8.00 2015 ARENA TRIALS BEACH CROSS BEACH RACING BIKE TRIALS BYMX CYCLE TRIALS DRAG ENDURO GRASS TRACK HARE & HOUNDS HILL CLIMB MOTOCROSS POCKET BIKES QUAD ROAD RACING SPEEDWAY SPRINT SUPERCROSS SUPERMOTO TRIALS HANDBOOK 2015 2015 HANDBOOK January 2015 All enquiries should be addressed to: The Auto-Cycle Union Ltd., ACU House, Wood Street, Rugby, Warwickshire CV21 2YX. Telephone: 01788 566400; Fax: 01788 573585 www.acu.org.uk [email protected] The contents of this Handbook are Copyright and must not be reproduced without written consent from the Auto-Cycle Union Ltd. The various regulations contained herein become effective as at 1st January 2014. This publication supersedes previous editions. The ACU is the internationally recognized National Governing Body for motorcycle sport in the British Isles (less Northern Ireland). Formed in 1903, the ACU has a long tradition in the world of motorcycle sport being a founder member of the World Governing Body, the Federation Internationale Motocyclisme (FIM). The ACU has a major role in furthering the interests of motorcycle sport on a global basis. Domestically, the ACU provides for all forms of motorcycle sport ranging from Road Racing to all disciplines of Off Road activity and has successfully organized world class events such as Moto GP, World Superbikes, the Isle of Man TT Races and the Motocross of Nations. The ACU aims to ensure that all people irrespective of their age, gender, disability, race, ethnic origin, creed, colour, social status or sexual orientation, have a genuine and equal opportunity to participate in motorcycle sport at levels in all roles. -

Passenger Information During Snow Disruption December 2010

Passenger information during snow disruption December 2010 A Rail passenger Information during snow disruption December 2010 Headline Findings 1. The National Rail Enquiries (NRE) website appears to have coped well with very high volumes 2. The online real time journey planner on the NRE website did not show correct information for some train operating companies (TOCs) 3. The online journey planners on TOC and third-party websites did not generally reflect the contingency timetables in operation 4. Tickets continued to be available for sale online for many trains that would not run 5. Station displays appear to have reflected formal contingency timetables, except for Southeastern 6. Station displays and online Live Departure Boards did not always keep pace with events 7. The NRE call centres appear to have provided good information, but queuing times of 11 or 12 minutes were common. 1 The National Rail Enquiries appears to have coped well with very high volumes We saw no evidence that the NRE website crashed or was slower than usual, despite a large spike in volume (Chris Scoggins reported that the volume on 2 December was twice the previous record peak on 7 January 2010). 2 The online real time journey planner on the NRE website did not show correct information for some train operating companies NRE had to advise passengers not to use the journey planner for enquiries about East Coast, Southeastern and South West Trains. This was a significant failure, with three scenarios: 2a Although the journey planner showed services from a contingency timetable for East Coast on 1 and 2 December, it also showed services from the base timetable that were no longer running. -

The Demand for Public Transport: a Practical Guide

The demand for public transport: a practical guide R Balcombe, TRL Limited (Editor) R Mackett, Centre for Transport Studies, University College London N Paulley, TRL Limited J Preston, Transport Studies Unit, University of Oxford J Shires, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds H Titheridge, Centre for Transport Studies, University College London M Wardman, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds P White, Transport Studies Group, University of Westminster TRL Report TRL593 First Published 2004 ISSN 0968-4107 Copyright TRL Limited 2004. This report has been produced by the contributory authors and published by TRL Limited as part of a project funded by EPSRC (Grants No GR/R18550/01, GR/R18567/01 and GR/R18574/01) and also supported by a number of other institutions as listed on the acknowledgements page. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting and funding organisations TRL is committed to optimising energy efficiency, reducing waste and promoting recycling and re-use. In support of these environmental goals, this report has been printed on recycled paper, comprising 100% post-consumer waste, manufactured using a TCF (totally chlorine free) process. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The assistance of the following organisations is gratefully acknowledged: Arriva International Association of Public Transport (UITP) Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC) Local Government Association (LGA) Confederation of Passenger Transport (CPT) National Express Group plc Department for Transport (DfT) Nexus Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Network Rail Council (EPSRC) Rees Jeffery Road Fund FirstGroup plc Stagecoach Group plc Go-Ahead Group plc Strategic Rail Authority (SRA) Greater Manchester Public Transport Transport for London (TfL) Executive (GMPTE) Travel West Midlands The Working Group coordinating the project consisted of the authors and Jonathan Pugh and Matthew Chivers of ATOC and David Harley, David Walmsley and Mark James of CPT. -

Getting Around Access Guide

Getting Around Access Guide Accessible public transport in the West Midlands April 2018 CONTENTS Preface Introduction 1. Who we are, what we do 2. Where to find travel information 3. Our equality commitment 4. Ring and Ride and Community Transport 5. Buses and coaches 6. Trains 7. Metro 8. Taxis and private hire vehicles 9. Tickets 10. Ensuring your safety and security 11. Further accessibility help 12. Toilet facilities 13. Other information About Network West Midlands West Midlands districts’ map West Midlands rail map 2018 Getting Around Guide reply card Blind and Disabled Pass reply card 1 PREFACE From Laura Shoaf Managing Director, Transport for West Midlands I am delighted to introduce this, the 24th edition of the Getting Around Access Guide. Accessible travel for the people of the West Midlands is an integral aspect of our goal of transforming public transport. I am sure that you will find this guide useful and that it provides all the information you need to improve your journey experience on the region’s public transport network. The past 12 months has been an exciting time for the West Midlands Combined Authority and within that Transport for West Midlands (TfWM). We were named best in the UK for the second year running after winning City Region Transport Authority of the Year at the National Transport Awards, in recognition of a number of key projects that TfWM had delivered, many of which are included here. The innovative West Midlands Bus Alliance was renewed, meaning passengers across the region can look forward to even higher standards of service and reliability, following the partnership’s first two successful years. -

Notices and Proceedings

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WALES) (CYMRU) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2001 PUBLICATION DATE: 27 March 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 17 April 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Wales) (Cymru) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 10/04/2014 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] The Welsh Traffic Area Office welcomes correspondence in Welsh or English. Ardal Drafnidiaeth Cymru yn croesawu gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg neu yn Saesneg. NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Wales) (Cymru) 38 George Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 1PL The public counter at the Birmingham office is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. -

Public Transport Procurement in Britain

This is a repository copy of Public Transport Procurement in Britain. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/159839/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Nash, C and Smith, A orcid.org/0000-0003-3668-5593 (2020) Public Transport Procurement in Britain. Research in Transportation Economics. ISSN 0739-8859 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100847 © 2020 Elsevier Ltd. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Public Transport Procurement in Britain Chris Nash and Andrew Smith Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds Key words Bus; rail; franchising; competitive tendering; competition JEL classification R41 Abstract Britain is one of the countries with the most experience of alternative ways of procuring public transport services. From a situation where most public transport services were provided by publicly owned companies, it has moved to a situation where most are private. -

Competition Issues in Road Transport 2000

Competition Issues in Road Transport 2000 The OECD Competition Committee debated competition issues in road transport in October 2000. This document includes an executive summary and the documents from the meeting: an analytical note by Mr. Darryl Biggar for the OECD, written submissions from Australia, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Spain, Turkey, the United States, as well as an aide-memoire of the discussion. The road transport sector, an essential mode of transport in OECD economies, is conventionally divided into two, largely unrelated, parts – the road freight industry and the road passenger industry. The sectors under discussion – trucking, buses, and taxis – have quite different characteristics and scope for competition, which reflect inter alia differences in the timeliness and economies of scale and scope in operations. Trucking can sustain high level of competition and to some extent buses as well while there is some debate as to how and what form of competition can be introduced in taxis. As in the air transport industry, international trucking is governed by restrictive bilateral treaties. Most countries have liberalised their domestic trucking sector, removing controls on entry and prices. In the bus industry, long-distance bus services are liberalised in some countries while intra-city or local buses are very rarely liberalised. The taxi industry appears at first sight to be competitive with many buyers and many sellers. Structural Reform in the Rail Industry (2005) Competition Policy and the Deregulation of Road Transport (1990) Unclassified DAFFE/CLP(2001)10 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 22-May-2001 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English - Or. -

7 March 2018

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH WEST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2801 PUBLICATION DATE: 07/03/2018 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 28/03/2018 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 14/03/2018 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North West of England) Suite 4 Stone Cross Place Stone Cross Lane North Golborne Warrington WA3 2SH General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information.