Divided Prairie City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framing a Complete Streets Checklist for Downtown Historic Districts and Character Neighbourhoods

Framing a Complete Streets Checklist for Downtown Historic Districts and Character Neighbourhoods: A Case Study of the Warehouse District, Winnipeg, Manitoba. by Pawanpreet Gill A Practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF CITY PLANNING Department of City Planning University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 by Pawanpreet Gill Abstract This Major Degree Project explores the concept of “complete streets” and the framing of an appropriate “complete streets” checklist for historic districts and character neighbourhoods in downtown contexts, attempting to learn especially from the case of Winnipeg’s Warehouse District Neighbourhood. A “complete streets” checklist is considered to include a combination of infrastructure and urban design considerations, such as sidewalks, bike lanes, intersections, transit stops, curb extensions, travel lane widths, and parking needs. It proceeds from the premise that if an individual street or system of streets is ‘complete’, individuals will be more likely to reduce the time spent using automobiles, and increase the time expended on walking, biking, or using other transit alternatives, while making travel on the streets safer and more enjoyable for all users. The MDP examines the current street-related infrastructure and uses within the Warehouse District Neighbourhood of Downtown Winnipeg and discusses the relevance of current or recent City of Winnipeg plans and proposals. Taking the form of a practicum, the research sought to inform and engage local planners, engineers and public officials regarding a “complete streets” approach to their work – primarily in terms of the recommended framing of a complete streets checklist as well as recommendations for future area improvements in the Warehouse District Neighbourhood, demonstrating the usefulness of the checklist. -

Final Report DE Comments

Final Report July 24, 2013 BIKE TO WORK DAY FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2013 FINAL REPORT Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 1 Final Report July 24, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................. page 2 a. Event Background 2 b. 2013 Highlights 4 2. Planning Process......................................... page 5 a. Steering Committee 5 b. Event Coordinator Hours 7 c. Volunteers 8 d. Planning Recommendations 8 3. Events............................................................ page 9 a. Countdown Events 9 b. Pit Stops 12 c. BBQ 15 d. Event Recommendations 17 4. Sponsorship................................................... page 18 a. Financial Sponsorship 18 b. In Kind Sponsorship 20 c. Prizes 23 d. Sponsorship Recommendations 24 5. Budget........................................................... page 25 6. Media & Promotions..................................... page 27 a. Media Conference 27 b. Website-biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 28 c. Enewsletter 28 d. Facebook 28 e. Twitter 29 f. Print & Digital Media 29 g. Media Recommendations 29 7. Design............................................................ page 31 a. Logo 31 b. Posters 31 c. T-shirts 32 d. Banners 32 e. Free Press Ad 33 f. Bus Boards 33 g. Handbills 34 h. Design Recommendations 34 8. T-shirts............................................................ page 35 a. T-shirt Recommendations 36 9. Cycling Counts............................................. page 37 10. Feedback & Recommendations............... page 41 11. Supporting Documents.............................. page 43 a. Critical Path 43 b. Media Release 48 c. Sample Sponsorship Package 50 d. Volunteer List 55 Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 2 Final Report July 24, 2013 1. INTRODUCTION Winnipeg’s 6th Annual Bike to Work Day was held on Friday, June 21st, 2013. The event consisted of countdown events from June 17-21st, online registration, morning pit stops and an after work BBQ with free food and live music. -

Point Douglas (“The North End”) a Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and Their Children

Point Douglas (“The North End”) A Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and their Children North Point Douglas Point Lord Selkirk Park Dufferin Douglas William Whyte Burrows Central St. Johns Neighbourhoods Luxton Inkster-Faraday Robertson Mynarski South Point Douglas This guide is produced and maintained by the WRHA Point Douglas Community Health Office. For editing, revisions or other information regarding content, please contact Vince Sansregret @ 204-(801-7803) or email: [email protected] INDEX Community Leisure and Recreation Centres Page 2 City of Winnipeg Fee Subsidy Program Page 3 Public Computer Access sites Page 3 Licensed Child Care Facilities Page 4-5 Food Banks/Free Community Meal programs Page 6 Cooking Programs – Food Security Page 7 Discount Clothing, Furniture, Household items Page 8 Community Support Programs Page 9-11 Programs for Expecting Parents and Families with infants Page 12 Libraries / Family Literacy Page 13 Parent and Child/Parenting Support Programs Page 14-15 City of Winnipeg Priceless Fun FREE Programming Page 16 FREE Child/Youth Recreation/‘drop-in’ Programs Page 17-19 Adult Ed.-Career Preparation Programs Page 20-21 Community, Leisure and Recreation Centres Luxton Community Centre 210 St. Cross St. Win Gardner-North End Wellness Phone: 204- 582-8249 Center - YMCA 363 McGregor St. Norquay Community Centre Phone: 204-293-3910 65 Granville St. Phone: 204-943-6897 Turtle Island Neighbourhood Centre 510 King St Sinclair Park Community Phone: 204-986-8346 Centre 490 Sinclair Ave. William Whyte Neighbourhood Phone: 204-582-8257 Association – Pritchard Park Recreation Centre Ralph Brown Community 295 Pritchard Ave. Centre Phone: 204-582 – 0988 460 Andrews Street Phone: 204-586-3149 Sgt. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre’S John Hirsch Mainstage

ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre’s John Hirsch Mainstage. PHOTO BY JERRY GRAJEWSKI Inset: John Hirsch and Tom Hendry. Mandate It is the aim of the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre to study, practice and promote all aspects of the dramatic art, with particular emphasis on professional production. Mission The Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre exists to celebrate the widest spectrum of theatre art. Deeply rooted in the province of Manitoba, which gave it life and provides for its growth, Royal MTC aspires to both ABOUT ROYAL MTC reflect and engage the community it serves. When the Winnipeg Little Theatre and Theatre 77 merged to form Vision the Manitoba Theatre Centre in 1958, the goal was to produce great Royal MTC’s theatres and our province will theatre with mass appeal. Artistic Director John Hirsch and General teem with artists and audiences sharing in the act of imagining, enriching lives Manager Tom Hendry staged professional productions of an eclectic and communities. array of plays – classics, Broadway hits and new Canadian work. With the establishment of a second stage for experimental work in 1960, Values and an annual provincial tour that began in 1961, MTC fully realized Quality the original vision of a centre for theatre in Manitoba. Inspired by the A commitment to quality is reflected in the breadth and quality of MTC’s programming, a whole network of what writing of each play, in the actors, directors became known as “regional theatres” emerged across North America. and designers who create each production, and in the volunteers, staff, funders and Since its founding, MTC has produced more than 600 plays with audiences who support it. -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

Winnipeg Downtown Profile

WINNIPEG DOWNTOWN PROFILE A Special Report on Demographic and Housing Market Factors in Winnipeg’s Downtown IUS SPECIAL REPORT JULY-2017 Institute of Urban Studies 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg P: 204 982-1140 F: 204 943-4695 E: [email protected] Mailing Address: 515 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 Author: Scott McCullough, Jino Distasio, Ryan Shirtliffe Data & GIS: Ryan Shirtliffe Research: Ryan Shirtliffe, Scott McCullough Supporting Research: Brad Muller, CentreVenture The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. Introduction This study undertakes an analysis of demographic and housing market factors that may influence the need for incentives in the downtown Winnipeg housing market. This report informs CentreVenture’s proposed “10 Year Housing Evaluation” and helps to address the proposed question, “What price do new downtown housing projects need to achieve to encourage more people to move downtown?” To accomplish this, the following have been undertaken: 1. A Demographic Analysis of current downtown Winnipeg residents with a comparison to Winnipeg medians, 2. A Rental Market Analysis comparing downtown rates to Winnipeg averages, as well as changing rental rates in the downtown from Census data, 3. -

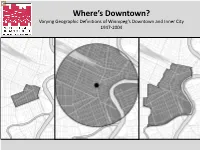

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Physician Directory

Physician Directory, Currently Practicing in the Province Information is accurate as of: 9/24/2021 8:00:12 AM Page 1 of 97 Name Office Address City Prov Postal Code CCFP Specialty Abara, Chukwuma Solomon Thompson Clinic, 50 Selkirk Avenue Thompson MB R8N 0M7 CCFP Abazid, Nizar Rizk Health Sciences Centre, Section of Neonatology, 665 William Avenue Winnipeg MB R3E 0L8 Abbott, Burton Bjorn Seven Oaks General Hospital, 2300 McPhillips Street Winnipeg MB R2V 3M3 CCFP Abbu, Ganesan Palani C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abbu, Kavithan Ganesan C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abdallateef, Yossra Virden Health Centre, 480 King Street, Box 400 Virden MB R0M 2C0 Abdelgadir, Ibrahim Mohamed Ali Manitoba Clinic, 790 Sherbrook Street Winnipeg MB R3A 1M3 Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology Abdelmalek, Abeer Kamal Ghobrial The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 Abdulrahman, Suleiman Yinka St. Boniface Hospital, Room M5038, 409 Tache Avenue Winnipeg MB R2H 2A6 Psychiatry Abdulrehman, Abdulhamid Suleman 200 Ste. Anne's Road Winnipeg MB R2M 3A1 Abej, Esmail Ahmad Abdullah Winnipeg Clinic, 425 St. Mary Ave Winnipeg MB R3C 0N2 CCFP Gastroenterology, Internal Medicine Abell, Margaret Elaine 134 First Street, Box 70 Wawanesa MB R0K 2G0 Abell, William Robert Rosser Avenue Medical Clinic, 841 Rosser Avenue Brandon MB R7A 0L1 Abidullah, Mohammad Westman Regional Laboratory, Rm 146 L, 150 McTavish Avenue Brandon MB R7A 7H8 Anatomical Pathology Abisheva, Gulniyaz Nurlanbekovna Pine Falls Health Complex, 37 Maple Street, Box 1500 Pine Falls MB R0E 1M0 CCFP Abo Alhayjaa, Sahar C W Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 Obstetrics & Gynecology Abou-Khamis, Rami Ahmad Northern Regional Health, 867 Thompson Drive South Thompson MB R8N 1Z4 Internal Medicine Aboulhoda, Alaa Samir The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 General Surgery Abrams, Elissa Michele Meadowwood Medical Centre, 1555 St. -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 the Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (Pages 12-43 from Highlights from the Winnipeg Foundation’S 2020 Year)

Endowment Funds 1921-2020 The Winnipeg Foundation September 30, 2020 (pages 12-43 from Highlights from The Winnipeg Foundation’s 2020 year) Note: If you’d like to search this document for a specific fund, please follow these instructions: 1. Press Ctrl+F OR click on the magnifying glass icon (). 2. Enter all or a portion of the fund name. 3. Click Next. ENDOWMENT FUNDS 1921 - 2020 Celebrating the generous donors who give through The Winnipeg Foundation As we start our centennial year we want to sincerely thank and acknowledge the decades of donors from all walks of life who have invested in our community through The Winnipeg Foundation. It is only because of their foresight, commitment, and love of community that we can pursue our vision of “a Winnipeg where community life flourishes for all.” The pages ahead contain a list of endowment funds created at The Winnipeg Foundation since we began back in 1921. The list is organized alphabetically, with some sub-fund listings combined with the main funds they are connected to. We’ve made every effort to ensure the list is accurate and complete as of fiscal year-end 2020 (Sept. 30, 2020). Please advise The Foundation of any errors or omissions. Thank you to all our donors who generously support our community by creating endowed funds, supporting these funds through gifts, and to those who have remembered The Foundation in their estate plans. For Good. Forever. Mr. W.F. Alloway - Founder’s First Gift Maurice Louis Achet Fund The Widow’s Mite Robert and Agnes Ackland Memorial Fund Mr. -

A Matter of Political Responsibility : Real Property Assessment in Winnipeg

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by WinnSpace Repository A Matter of Political Responsibility: Real Property Assessment in Winnipeg Research and Working Paper No. 12 __________________ by Alan F.J. Artibise 1984 __________________ The Institute of Urban Studies FOR INFORMATION: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg phone: 204.982.1140 fax: 204.943.4695 general email: [email protected] Mailing Address: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 515 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 A MATTER OF POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY: REAL PROPERTY ASSESSMENT IN WINNIPEG Research and Working Paper No. 12 Published 1984 by the Institute of Urban Studies, University of Winnipeg © THE INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES Note: The cover page and this information page are new replacements, 2015. The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. A MATTER OF POLITICAL RESPONSIBILITY: REAL PROPERTY ASSESSMENT IN WINNIPEG Research and Working Paper No. 12 by Alan F.J. Artibise Institute of Urban Studies 1984 CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Artibise, Alan F.J. 1946 - A matter of political responsibility (Research and working paper; no.