A Critical Analysis of Childcare Waiting Lists in Winnipeg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report DE Comments

Final Report July 24, 2013 BIKE TO WORK DAY FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2013 FINAL REPORT Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 1 Final Report July 24, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................. page 2 a. Event Background 2 b. 2013 Highlights 4 2. Planning Process......................................... page 5 a. Steering Committee 5 b. Event Coordinator Hours 7 c. Volunteers 8 d. Planning Recommendations 8 3. Events............................................................ page 9 a. Countdown Events 9 b. Pit Stops 12 c. BBQ 15 d. Event Recommendations 17 4. Sponsorship................................................... page 18 a. Financial Sponsorship 18 b. In Kind Sponsorship 20 c. Prizes 23 d. Sponsorship Recommendations 24 5. Budget........................................................... page 25 6. Media & Promotions..................................... page 27 a. Media Conference 27 b. Website-biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 28 c. Enewsletter 28 d. Facebook 28 e. Twitter 29 f. Print & Digital Media 29 g. Media Recommendations 29 7. Design............................................................ page 31 a. Logo 31 b. Posters 31 c. T-shirts 32 d. Banners 32 e. Free Press Ad 33 f. Bus Boards 33 g. Handbills 34 h. Design Recommendations 34 8. T-shirts............................................................ page 35 a. T-shirt Recommendations 36 9. Cycling Counts............................................. page 37 10. Feedback & Recommendations............... page 41 11. Supporting Documents.............................. page 43 a. Critical Path 43 b. Media Release 48 c. Sample Sponsorship Package 50 d. Volunteer List 55 Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 2 Final Report July 24, 2013 1. INTRODUCTION Winnipeg’s 6th Annual Bike to Work Day was held on Friday, June 21st, 2013. The event consisted of countdown events from June 17-21st, online registration, morning pit stops and an after work BBQ with free food and live music. -

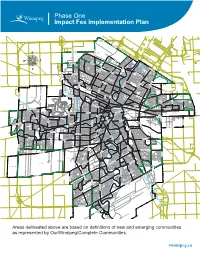

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

Recent Community Grants Approved January 2021 Arts, Culture and Heritage Organization Description Amount Associated Manitoba Arts Festivals Inc

Recent Community Grants Approved January 2021 Arts, Culture and Heritage Organization Description Amount Associated Manitoba Arts Festivals Inc. 2021 Provincial Music & Arts Festival $12,000 Camerata Nova Inc. Performance of Medieval Inuit $15,000 Canzona Inc Performance of Cori Spezzati $3,750 Contemporary Verse 2 Inc. Technical upgrades and costs related to transi- $9,000 tioning to online programming Crescent Fort Rouge United Church Community Activities Manager $7,500 Dancer Transition Resource Centre DRTC's Manitoba-based programming $5,000 Folk Arts Council of Winnipeg, Inc. Priority short-term operating costs $45,000 Friends of Dalnavert Museum Inc. Storytelling program at Dalnavert Museum $5,000 Gas Station Arts Centre Priority feasibility study costs $20,000 Graffiti Art Programming Inc. Free arts mentorship and after-school program- $25,000 ming to young artists in an adapted format Green Kids Inc Bike and Circuses summer 2021 performances $5,000 Manitoba Band Association Inc. 2021 Manitoba Band, Solo, & Ensemble Festival $30,000 Manitoba Chamber Orchestra Inc. Costs related to producing an online 2021 con- $20,000 cert season Manitoba Crafts Museum and Library Digital collections project $10,000 Inc. Manitoba Genealogical Society Inc. Priority costs related to website improvements $7,000 and developing a social media strategy Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Short-term operating costs $45,000 Centre Inc. One Trunk Theatre Inc. Priority aspects of the Transformation project $10,000 Plug-In Inc Priority project costs related to Stages 2021 $20,000 Prairie Fire Press Inc. Costs related to coordinating Prairie Fire Univer- $7,000 sity Royal Aviation Museum of Western Priority costs related to public and oral history $5,000 Canada Inc. -

Vendor Payments Over $50,000 20

FOR THE YEAR ENDED MARCH 31, 2020 Vendor Payments Over $50,000 20 VENDOR STATEMENT OF CONSOLIDATED FUND PAYMENTS IN EXCESS OF $50,000 TO CORPORATIONS, FIRMS, INDIVIDUALS, OTHER GOVERNMENTS AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2020 (UNAUDITED) ………………………………………………… INFORMATION 1. This statement lists, in alphabetical order within Department or Special Operating Agency, each payee whose total payments by that individual department or special operating agency exceeded $50,000 during the fiscal year. Payments are presented on a gross basis to show all amounts which were charged to the 2019-2020 fiscal period for the purchase of goods and services, investment and loan transactions, grant payments and refunds as well as payments from amounts held in trust on behalf of others. 2. Where a Department or Special Operating Agency did not have any payee meeting the threshold of total payments exceeding $50,000, it is noted that there are “NO REPORTING VENDORS”. 3. Where multiple, same name vendors are found within a city/town, they are applicable to different locations. 4. Where the name of a city/town appears twice, in succession, the first is attached to the vendor’s name, the second is applicable to the vendor’s address. 5. This statement also lists, in alphabetical order within department, vendors from whom departmental purchases, using the National Bank of Canada procurement cards, are equal to or exceeding $25,000 during the fiscal year. 6. Payments in other currencies are shown in the Canadian dollar equivalent at the time of payment. 7. The location of the payee is shown except where payment was made to an address in Winnipeg. -

Property Taxes and Built Form: Mapping the City of Winnipeg By: Felipe A

Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg$ X.xx - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - -

Socio-Economic Environment

Proposed Floodway Expansion Project August 2004 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS 8.0 SOCIO-ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT...................................................................... 1 8.1 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 1 8.2 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY............................................................................ 2 8.2.1 Pathways and Sources of Effect...........................................................................3 8.2.2 Geographic Area of Effect ...................................................................................5 8.2.3 Time Period of Effect ..........................................................................................9 8.2.4 Approach to Assessment.....................................................................................9 8.3 RESOURCE USE ..................................................................................................... 12 8.3.1 Approach and Methodology...............................................................................12 8.3.2 Existing Environment ........................................................................................14 8.3.3 Effects and Mitigation .......................................................................................28 8.3.4 Residual Effects and Significance .......................................................................40 8.3.5 Monitoring and Follow-Up .................................................................................43 -

For Immediate Release Friday, June 22, 2007 ADULT

For Immediate Release Friday, June 22, 2007 ADULT NUISANCE MOSQUITO FOGGING PROGRAM TO COMMENCE Starting Saturday – June 23, 2007 at 9:30 p.m. WEATHER PERMITTING Winnipeg, MB Today, the City of Winnipeg’s Insect Control Branch is providing public notice that an Adult Nuisance Mosquito Fogging Program for the entire city will begin effective Saturday, June 23, 2007 at 9:30 p.m. This adult nuisance mosquito fogging program will be carried out in the entire City, respecting buffer zones, and prioritizing for areas with the highest nuisance mosquito populations. Weather permitting, the adult nuisance mosquito fogging program will begin Saturday evening in the following areas: Insect Management Area Neighborhoods Betsworth, Ridgewood South, River West Park, Roblin Park, Southboine, 26 Westdale Elmhurst, Eric Coy, Marlton, Ridgedale, Varsity View, Vialoux 27 Assiniboine Downs, Buchanan, Kirkfield, Glendale, Westwood 34 Crestview, Heritage Park, Saskatchewan North, Sturgeon Creek 35 Birchwood, Booth, Jameswood, Murray Industrial Park, Silver Heights, 36 Woodhaven Airport 37 Bruce Park, Deer Lodge, King Edward 38 Brooklands, Sargent Park, St. James Industrial 39 Central Park, Colony, Daniel McIntyre, Portage - Ellice, Spence, West 42 Alexander North Inkster Industrial, Oakpoint Highway, Omand's Creek Industrial, 43 Tyndall Park Burrows - Keewatin, Inkster Industrial Park, Mynarski, Pacific Industrial, 44 Shaughnessy Park, Weston, Weston Shops Burrows Central, Robertson, William Whyte 45 Centennial, China Town, Civic Centre, Dufferin, Dufferin -

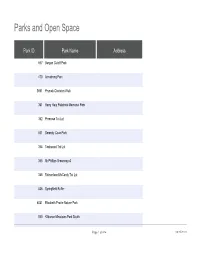

Parks and Open Space

Parks and Open Space Park ID Park Name Address 657 Bergen Cutoff Park 470 Armstrong Park 3661 Prymak-Chelston Walk 351 Harry Hatz Palatnick Memorial Park 352 Primrose Tot Lot 501 Serenity Cove Park 354 Teakwood Tot Lot 355 McPhillips Greenway-4 358 Richardson-McCurdy Tot Lot 536 Springfield Buffer 6041 Elizabeth Prairie Nature Park 540 Kildonan Meadows Park South Page 1 of 624 09/25/2021 Parks and Open Space Location Description Park Category 1235 Kildonan Dr Park and Open Space 1030 Munroe Ave Park and Open Space Between 59 & 71 Steve Mymko Dr Park and Open Space 1 Dahlia Ave Park and Open Space 46 Primrose Cres Park and Open Space 56 Melonlea Cv Park and Open Space 105 Teakwood Ave Park and Open Space E side McPhillips St between Dafoe Bv & Richardson Ave Park and Open Space 33 McCurdy St Park and Open Space Between Springfield Rd & Molson St Park and Open Space SW of Plessis Rd & St. Boniface Rd Park and Open Space 195 Kildonan Meadow Dr Park and Open Space Page 2 of 624 09/25/2021 Parks and Open Space Linear Park System District KILDONAN Parkway East East East North North East North North North East East East Page 3 of 624 09/25/2021 Parks and Open Space Neighbourhood Electoral Ward CCA KILDONAN DRIVE North Kildonan River East MUNROE EAST Elmwood - East Kildonan River East PEGUIS Transcona Transcona GARDEN CITY Old Kildonan Seven Oaks GARDEN CITY Old Kildonan Seven Oaks RIVER EAST North Kildonan River East GARDEN CITY Old Kildonan Seven Oaks GARDEN CITY Old Kildonan Seven Oaks GARDEN CITY Old Kildonan Seven Oaks SPRINGFIELD SOUTH North Kildonan River East ST. -

William R. Clement Parkway Extension Functional & Preliminary Design Study Welcome

1 Welcome William R. Clement Parkway Extension Functional & Preliminary Design Study PUBLIC INFORMATION DISPLAY SESSION March 19, 2015 Public Information Display Session Format 1 Please use the sticky notes provided to post comments directly on the presentation boards. Project staff are happy to answer your questions. Please complete a comment sheet and submit it prior to leaving Purpose of the Study 2 The William R. Clement Parkway (WRCP) is: » An important component of the City’s Strategic Road Network to accommodate the travel demand in west Winnipeg. » Intended to provide an important north-south link in west Winnipeg. » This project is an Engineering study, funding for construction is currently not in place. Place Comments Here Recommended Extension 3 PORTAG Rout E Route 62 85 ACADEMY Route 95 OSBORNE The City of Winnipeg Transportation Master Plan Route 95 CORYDON Route Route CORYDON70 Route 96 Route 42 ROBLIN 90 241 Route GRANT Route GRANT Route 105 105 125 (TMP) Recommends WRCP Extension TAYLOR KENASTON 100 M A N I TO B A Route WILKES 145 Route 80 MCGILLIVRAY » “The purpose of the TMP is to present a 427 Route IN 90 Route PEMBINA 155 BISHOP GRAND WAVERLEY long-term strategy to guide the planning, Route 165 WRCP WILLIAM R. CLEMENT PARKWAY CHANCELLOR development, renewal and maintenance of a 3 MATHESON Route Extension 42 Route 100 80 multi-modal transportation system in a manner 100 that is consistent with project needs, and ST. MARY 100 M 2 A N IT OB A 200 aligned with the City’s growth and the overall 3 PEMBIN A 7 8 PERIMETER HIGHWAY 6 101 9 vision for a sustainable Winnipeg and region.” 101 204 Rou te 180 Route CHIEF PEGUIS TRAIL 90 59 PTH 6 EXTENSION Rout 42 e Rou Rout te e BROOKSIDE BROOKSIDE 23 LEILA 17 Route INKSTER 25 INKSTER FUTURE PR221 MCPHILLIPS 101 Route OAK POINT 52 KEEWATIN Y KEEWATIN A W 101 A WAY D A N A C ARLINGTON T Route SALTER Route Route MCGREGOR R 47 SELKIRK HENDERSON HWY 20 O 90 MAIN Rou RALEIGH/GATECONCORDIA P te E 62 R T N CE STURGEON LOGAN Route PARKWAY » PARKWAY 57 NOTRE DAME ST. -

Appendix D: Ward Detail Report, 2020 Report on Parks and Open Space Assets

Appendix D: Ward Detail Report, 2020 Report on Parks and Open Space Assets Asset data as of September 30, 2020 Table of Contents Electoral Ward Page Charleswood ‐ Tuxedo ‐ Westwood 3 Daniel McIntyre 28 Elmwood ‐ East Kildonan 40 Fort Rouge ‐ Fort Garry 54 Mynarski 72 North Kildonan 90 Old Kildonan 109 Point Douglas 128 River Heights ‐ Fort Garry 146 St. Boniface 163 St. James 190 St. Norbert ‐ Seine River 214 St. Vital 232 Transcona 253 Waverley West 279 Outside City Limit 292 Electoral Ward: Charleswood ‐ Tuxedo ‐ Westwood Parks and Open Space Listed by Name, Location and Size AREA NAME OF PARK OR OPEN SPACE LOCATION/ADDRESS (HA) Aldershot Strip 5 Aldershot Blvd 0.34 Assiniboine Forest 950 Shaftesbury Blvd 292.20 Assiniboine Park 6 Locomotive Dr 163.31 Assiniboine Woods‐Great Elm Buffer N side Roblin Blvd between William Marshall Wy & 0.30 Lannoo Dr Assiniboine Woods‐Sanders Buffer NW Roblin Blvd & William Marshall Wy 0.11 Bannatyne Grove 5605 Roblin Blvd 0.34 Bard Place Park N of Bard Place E of Shaftesbury Blvd 0.78 Barker Buffer NE Roblin Blvd & Barker Blvd 0.04 Beauchemin Park 5921 Southboine Dr 3.81 Beaumont School Park E side Civic St, S of Betsworth Ave 1.91 Beaverdam Creek 75 Carlotta Cres 1.12 Beaverdam Creek Greenway Between Buckle Dr, Carlotta Cres & Carlos Ln 0.25 Beaverdam Creek Window 544 Berkley St 0.11 Bedson Park 460 Bedson St 1.08 Benjaminson Park 3432 Assiniboine Ave 0.14 Berkley Square 635 Berkley St 0.27 Birkenhead Strip 15 Devonport Blvd 0.49 Bramble Drive Park 29 Bramble Dr 0.31 Browning Boulevard Extension 254 -

Free Programs Recreation Is for Everyone! What Services Are Eligible for Fee Subsidies?

priceless fun Spring • Summer 2019 free programs Recreation is for Everyone! What services are eligible for fee subsidies? 1. Facility Passes 2. Program Subsidies Admission to the City of Winnipeg’s recreation facilities Registered Leisure Guide activities (including skating & (swimming pools and leisure centres). Valid for one year swimming) as well as drop-in active living programs. from the date issued. Who qualifies? You must be a City of Winnipeg resident People in Household Household Income & one of the following must apply: 1 $25,338 2 $31,544 hold a social assistance case number 3 $38,780 4 $47,084 hold a refugee assistance number 5 $53,402 family income is below the low income cut-off (LICO) 6 $60,228 listed in chart 7 $67,055 More than 7 for each additional person, add $6,827 Other considerations may be made for special circumstances. *Sources: Statistics Canada & Canadian Immigration & Citizenship How to apply Fill out an Provide verification Mail or email 1 application form 2 of economic need 3 application form Forms available at: Include a copy of one of the following: and verification of • winnipeg.ca/feesubsidy (If it has not already been supplied in the past economic need 12 months) • City of Winnipeg Mail: Fee Subsidy Program • Social assistance budget letter Recreation Facilities Community Services Department (see listing in this guide) • Refugee assistance case number 7th Floor, 395 Main St. (including case worker’s name & phone number) • 395 Main St. Winnipeg, MB R3B 3N8 • Most recent Canada Revenue Agency Mon–Fri (except holidays), Notice of Assessment identifying Email: [email protected] 8:30 am–4:30 pm annual net income (including Notice of Assessment for your spouse / partner) What happens next? • Monthly income statement from You will receive a letter indicating the CPP Disability outcome of your application in the mail. -

A City at Leisure, an Illustrated History

• A CITY AT LEISURE An Illustrated History of Recreation Services in Winnipeg /IPEN ( t4AR181999 A CITY AT LEISURE: &LIC AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF PARKS AND RECREATION SERVICES IN WINNIPEG 1893-1993 BY CATHERINE MACDONALD Copyright ©City of Winnipeg, Parks and Recreation Department, 1995 Published by the City of Winnipeg, Parks and Recreation Department Manitoba Cataloguing in Publication Data: Macdonald, Catherine Logan. A City at Leisure. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-7711-1436-2 1. Recreation -- Manitoba -- Winnipeg -- History. 2. Parks -- Manitoba -- Winnipeg -- History. 3. Community centers -- Manitoba -- Winnipeg -- History. 4. Leisure -- Manitoba -- Winnipeg -- History. 5. Winnipeg (Man.). Parks and Recreation Dept. -- History. I. Winnipeg (Man.). Parks and Recreation Dept. I. Title. FC3396.65M32 1994 790’097127’069 GV56.M3W5 1994 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. Cover Photo: Playground sports day at Assiniboine Park c. 1910. WPRD. 11 111 GREETINGS FROM THE MAYOR City leaders of some 100 years ago are to be acknowledged for recognizing that recreation and parks are an integral part of the social fabric of a GREAT CITY. The Winnipeg Women’s Labour Council and the Winnipeg City Council advocated the establish ment of the Parks and Recreation Department in 1893. Their deci sion set the stage for the development of the comprehensive parks and recreation system which is enjoyed by all City of Winnipeg residents today. Through the foresight and continuing hard work of volunteers, elected officials, and employees the City of Winnipeg is acknowl edged as a leader in the development of beautiful parks, innovative facilities and a full complement of recreation programs and ser vices.