Rental Housing Supply in Winnipeg: a Spatial Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report DE Comments

Final Report July 24, 2013 BIKE TO WORK DAY FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2013 FINAL REPORT Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 1 Final Report July 24, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................. page 2 a. Event Background 2 b. 2013 Highlights 4 2. Planning Process......................................... page 5 a. Steering Committee 5 b. Event Coordinator Hours 7 c. Volunteers 8 d. Planning Recommendations 8 3. Events............................................................ page 9 a. Countdown Events 9 b. Pit Stops 12 c. BBQ 15 d. Event Recommendations 17 4. Sponsorship................................................... page 18 a. Financial Sponsorship 18 b. In Kind Sponsorship 20 c. Prizes 23 d. Sponsorship Recommendations 24 5. Budget........................................................... page 25 6. Media & Promotions..................................... page 27 a. Media Conference 27 b. Website-biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 28 c. Enewsletter 28 d. Facebook 28 e. Twitter 29 f. Print & Digital Media 29 g. Media Recommendations 29 7. Design............................................................ page 31 a. Logo 31 b. Posters 31 c. T-shirts 32 d. Banners 32 e. Free Press Ad 33 f. Bus Boards 33 g. Handbills 34 h. Design Recommendations 34 8. T-shirts............................................................ page 35 a. T-shirt Recommendations 36 9. Cycling Counts............................................. page 37 10. Feedback & Recommendations............... page 41 11. Supporting Documents.............................. page 43 a. Critical Path 43 b. Media Release 48 c. Sample Sponsorship Package 50 d. Volunteer List 55 Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 2 Final Report July 24, 2013 1. INTRODUCTION Winnipeg’s 6th Annual Bike to Work Day was held on Friday, June 21st, 2013. The event consisted of countdown events from June 17-21st, online registration, morning pit stops and an after work BBQ with free food and live music. -

Point Douglas (“The North End”) a Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and Their Children

Point Douglas (“The North End”) A Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and their Children North Point Douglas Point Lord Selkirk Park Dufferin Douglas William Whyte Burrows Central St. Johns Neighbourhoods Luxton Inkster-Faraday Robertson Mynarski South Point Douglas This guide is produced and maintained by the WRHA Point Douglas Community Health Office. For editing, revisions or other information regarding content, please contact Vince Sansregret @ 204-(801-7803) or email: [email protected] INDEX Community Leisure and Recreation Centres Page 2 City of Winnipeg Fee Subsidy Program Page 3 Public Computer Access sites Page 3 Licensed Child Care Facilities Page 4-5 Food Banks/Free Community Meal programs Page 6 Cooking Programs – Food Security Page 7 Discount Clothing, Furniture, Household items Page 8 Community Support Programs Page 9-11 Programs for Expecting Parents and Families with infants Page 12 Libraries / Family Literacy Page 13 Parent and Child/Parenting Support Programs Page 14-15 City of Winnipeg Priceless Fun FREE Programming Page 16 FREE Child/Youth Recreation/‘drop-in’ Programs Page 17-19 Adult Ed.-Career Preparation Programs Page 20-21 Community, Leisure and Recreation Centres Luxton Community Centre 210 St. Cross St. Win Gardner-North End Wellness Phone: 204- 582-8249 Center - YMCA 363 McGregor St. Norquay Community Centre Phone: 204-293-3910 65 Granville St. Phone: 204-943-6897 Turtle Island Neighbourhood Centre 510 King St Sinclair Park Community Phone: 204-986-8346 Centre 490 Sinclair Ave. William Whyte Neighbourhood Phone: 204-582-8257 Association – Pritchard Park Recreation Centre Ralph Brown Community 295 Pritchard Ave. Centre Phone: 204-582 – 0988 460 Andrews Street Phone: 204-586-3149 Sgt. -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization

Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization: CentreVenture’s Involvement in the Redevelopment of Downtown Winnipeg by Elisabeth Saftiuk A practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of City Planning Department of City Planning University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 Elisabeth Saftiuk Abstract Downtowns contribute significantly to the economy of cities and as a result, decision makers are increasingly recognizing the fundamental value and importance of maintaining viable downtown cores. Following the post-war era of urban decay and suburban expansion, there have been widespread attempts nationwide to reverse trends and to revitalize downtowns. In the Winnipeg context, urban renewal was practiced throughout the 1960s and 1970s; tripartite agreements were utilized during the 1980s; and development corporations were introduced throughout the 1980s and 1990s as a way to encourage private sector investment with targeted public sector investments. This practicum investigates the relationship between planning and development in the downtown revitalization context. In particular, this research aims to discover the extent to which a downtown development agency may have facilitated the better integration of planning and development in a city’s downtown, where revitalization has been very much on the public agenda. Winnipeg’s CentreVenture Development Corporation was used as a case study to explore this relationship. It was established in 1999 and continues to operate today. This paper attempts to determine the extent of its involvement, and the manner by which this arms-length government agency has aided and influenced tangible development in Winnipeg’s downtown. -

A Critical Analysis of Childcare Waiting Lists in Winnipeg

The Waiting Game: A Critical Analysis of Childcare Waiting Lists in Winnipeg Michelle Albl A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2012 by Michelle Albl Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84962-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84962-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

April 2019 Availability Report

APRIL 2019 AVAILABILITY REPORT INDUSTRIAL OFFICE RETAIL LAND & INVESTMENT FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE www.cwstevenson.ca Independently Owned and Operated / A Member of the Cushman & Wakefield Alliance ©2018 Cushman & Wakefield. All rights reserved. The information contained in this communication is strictly confidential. This information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been verified. NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE CONDITION OF THE PROPERTY (OR PROPERTIES) REFERENCED HEREIN OR AS TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO ERRORS, OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITIONS, WITHDRAWAL WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY SPECIAL LISTING CONDITIONS IMPOSED BY THE PROPERTY OWNER(S). ANY PROJECTIONS, OPINIONS OR ESTIMATES ARE SUBJECT TO UNCERTAINTY AND DO NOT SIGNIFY CURRENT OR FUTURE PROPERTY PERFORMANCE. INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE www.cwstevenson.ca CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE APRIL 2019 *Please click the property image for more details. CAM RENTAL & CONTACT ADDRESS ZONING UNIT/SUITE AREA AVAILABLE LOADING MAX CLR HT RATE TAX COMMENTS (SF +/-) GRADE DOCK (+/-) (PSF) (PSF) 26 BUNTING STREET TYSON PREISENTANZ M2 8,283 1 3 16' $7.50 $3.00 • Located in the heart of Inkster Industrial 204 928 5002 Park close to major trucking routes and many amenities • (+/-) 1,000 sf office build out • Great parking BROOKSIDE LOT 4 CHRIS MACSYMIC I2 6,750 - 39,875 24’ TBD TBD NEW STATE OF THE ART 204 928 5019 INDUSTRIAL BUILDING • Strategically located within CentrePort Canada TYSON PREISENTANZ • No city of Winnipeg business taxes 204 928 5002 • Direct access to CentrePort Canada Way and Route 90 in close proximity to the Winnipeg RYAN MUNT James A. -

Gentrification in West Broadway?

Gentrification in West Broadway? Contested Space in a Winnipeg Inner City Neighbourhood By Jim Silver ISBN 0-88627-463-x May 2006 About the Author Jim Silver is a Professor of Politics at the University of Winnipeg, and a member of the Board of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Acknowledgements For their various contributions to this project, I am grateful to Roger Barske, Nigel Basely, Ken Campbell, Paul Chorney, Matt Friesen, Linda Gould, Brian Grant, Rico John, Darren Lezubski, Jennifer Logan, John Loxley, Shauna MacKinnon, Brian Pannell, Boyd Poncelet, Bob Shere and Linda Williams. Thanks also to the University of Winnipeg for awarding a Major Research Grant that made research for this project possible. This report is available free of charge from the CCPA website at www.policyalternatives.ca. Printed copies may be ordered through the Manitoba Office for a $10 fee. CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES–MB 309-323 Portage Ave., Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3B 2C1 PHONE (204) 927-3200 FAX (204) 927-3201 EMAIL [email protected] www.policyalternatives.ca/mb Contents 5 Introduction 7 1 Gentrification: A Brief Review of the Literature 12 2 The West Broadway Neighbourhood 18 3 The Dangers of Gentrification 20 4 Evidence of Gentrification in West Broadway 25 5 Why is Gentrification Occurring in West Broadway? 28 6 The Importance of Low-Income Rental Housing for West Broadway’s Future 31 7 Prospects for West Broadway 33 References GENTRIFicATION in WEST BROADWAY? Contested Space in a Winnipeg Inner City Neighbourhood By Jim Silver Since the mid-20th century, urban decline has rehabilitation of deteriorated but architecturally become almost ubiquitous in North American unique housing, stabilization of the population inner city neighbourhoods. -

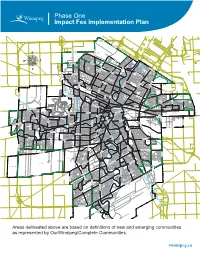

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

West Kildonan Committee Was Held This Day at 4:02 P.M

West Committee Room Council Building, Winnipeg June 8, 2010 A Meeting of the Lord Selkirk - West Kildonan Committee was held this day at 4:02 p.m. Members of the Committee: Councillor O’Shaughnessy, Chairperson Councillor Pagtakhan Winnipeg Public Service: Ms I. Skundberg, Clerk, City Clerk’s Department Mr. B. Buyachok, Real Property Officer, Planning, Property and Development Department Mr. S. Chapman, Traffic Studies Engineer, Public Works Department Mr. G. Doney, Senior Planner, Planning, Property and Development Department Ms S. Matile, Land Development Engineer, Planning, Property and Development Department Mr. K. Nixon, Active Transportation Coordinator, Public Works Department MOTIONS Moved by Councillor Pagtakhan, That Councillor Lazarenko be granted a leave of absence from today’s meeting due to a personal family matter. Carried Moved by Councillor Pagtakhan, That the minutes of the meeting held on May 11, 2010, be taken as read and confirmed. Carried Minutes - Lord Selkirk - West Kildonan Community Committee – June 8, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS DELEGATIONS 219. Wayne Conover, 817 Main North Point Douglas, Manor Tenant Advisory Committee (See Minute 230) 220. Anders Swanson, Co-Chair, W.R.E.N.C.H. (See Minute 237) 221. Richard Dudek, Vice-Presidemt. North Winnipeg Nomads Football Club Inc. (See Minute 239) REPORTS 222. Seven Oaks House Museum Board – Minutes 223. Applications for Citizen Member Appointments- Seven Oaks House Museum Board 224. Additional Appropriation – Western Canada Aviation Museum Inc. 225. Per Capita Grant - Luxton Playcentre Inc 226. Per Capita Grant – Edmund Partridge School Band Program 227. Per Capita Grant – 470 Pacific Tenant Association 228. Per Capita Grant – Dufferin School 229. -

Lead Concentrations in Soil in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods

Summary of Findings: Lead Concentrations in Soil in Winnipeg Neighbourhoods The Province of Manitoba, as represented by the Ministers of Health, Seniors and Active Living and Sustainable Development, commissioned an independent review of the potential health risks associated with lead in soils throughout the City of Winnipeg. This review was completed by a team led by Intrinsik Corp., in association with Habitat Health Impact Consulting, which included certified toxicologists, risk assessors, and a medical doctor. It included an evaluation of the benefits of conducting further investigations and provided recommendations regarding risk management and communication related to lead in soils. The work was completed between May and November 2019 and was divided into five tasks: • Task 1: Review of available soil data for Winnipeg neighbourhoods. • Task 2: Review of current and historical sources of lead in Winnipeg. • Task 3: Review of approaches used by Canadian and Western jurisdictions for assessing and managing lead in soil. • Task 4: Assessment of health risks associated with the lead concentrations measured in Winnipeg soils. • Task 5: Recommendations for further assessment of risks and possible risk management options. Summaries of the activities completed under each Task along with the key findings are presented below. Task 1: Review of Available Soil Data for Winnipeg Neighbourhoods Since the mid-1970s, the Province of Manitoba has completed several studies to measure the level of lead in Winnipeg soils. The focus was on the most recent studies completed by the Province, as well as a study conducted by the University of Manitoba for the neighbourhood of St. Boniface. All of the reported soil results were compared with the current health-based guideline for residential soils available from the Canadian Council for Ministers of the Environment. -

Recent Community Grants Approved January 2021 Arts, Culture and Heritage Organization Description Amount Associated Manitoba Arts Festivals Inc

Recent Community Grants Approved January 2021 Arts, Culture and Heritage Organization Description Amount Associated Manitoba Arts Festivals Inc. 2021 Provincial Music & Arts Festival $12,000 Camerata Nova Inc. Performance of Medieval Inuit $15,000 Canzona Inc Performance of Cori Spezzati $3,750 Contemporary Verse 2 Inc. Technical upgrades and costs related to transi- $9,000 tioning to online programming Crescent Fort Rouge United Church Community Activities Manager $7,500 Dancer Transition Resource Centre DRTC's Manitoba-based programming $5,000 Folk Arts Council of Winnipeg, Inc. Priority short-term operating costs $45,000 Friends of Dalnavert Museum Inc. Storytelling program at Dalnavert Museum $5,000 Gas Station Arts Centre Priority feasibility study costs $20,000 Graffiti Art Programming Inc. Free arts mentorship and after-school program- $25,000 ming to young artists in an adapted format Green Kids Inc Bike and Circuses summer 2021 performances $5,000 Manitoba Band Association Inc. 2021 Manitoba Band, Solo, & Ensemble Festival $30,000 Manitoba Chamber Orchestra Inc. Costs related to producing an online 2021 con- $20,000 cert season Manitoba Crafts Museum and Library Digital collections project $10,000 Inc. Manitoba Genealogical Society Inc. Priority costs related to website improvements $7,000 and developing a social media strategy Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Short-term operating costs $45,000 Centre Inc. One Trunk Theatre Inc. Priority aspects of the Transformation project $10,000 Plug-In Inc Priority project costs related to Stages 2021 $20,000 Prairie Fire Press Inc. Costs related to coordinating Prairie Fire Univer- $7,000 sity Royal Aviation Museum of Western Priority costs related to public and oral history $5,000 Canada Inc. -

Adult Nuisance Mosquito Fogging Program Starts Tonight

Adult Nuisance Mosquito Fogging Program starts tonight Winnipeg, MB – The City of Winnipeg will start its adult nuisance mosquito fogging program tonight at 9:30 p.m. Crews will treat in Insect Management Areas 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, and 51. This includes the following neighbourhoods: Insect Management Area Neighbourhoods 34 Assiniboia Downs, Buchanan, Kirkfield, Glendale, Westwood 35 Crestview, Heritage Park, Saskatchewan North, Sturgeon Creek Birchwood, Booth, Jameswood, Murray Industrial Park, Silver Heights, 36 Woodhaven 37 Airport 38 Bruce Park, Deer Lodge, King Edward 39 Brooklands, Sargent Park, St. James Industrial 40 Kensington, Minto, Polo Park, St. Matthews, West Wolseley Armstrong Point, Broadway - Assiniboine, Legislature, Portage & Main, 41 South Portage, The Forks, West Broadway, Wolseley Central Park, Colony, Daniel McIntyre, Portage - Ellice, Spence, West 42 Alexander North Inkster Industrial, Oakpoint Highway, Omand's Creek Industrial, 43 Tyndall Park Burrows - Keewatin, Inkster Industrial Park, Mynarski, Pacific Industrial, 44 Shaughnessy Park, Weston, Weston Shops 45 Burrows Central, Robertson, William Whyte Centennial, China Town, Civic Centre, Dufferin, Dufferin Industrial, 46 Exchange District, Logan C.P.R., Lord Selkirk Park, North Point Douglas, South Point Douglas 47 Inkster - Faraday, Luxton, St. John's, St. John's Park 48 Inkster Gardens, Mandalay West, The Maples Garden City, Leila - McPhillips Triangle, Margaret Park, Templeton - 49 Sinclair 50 Jefferson, Kildonan Park, Seven Oaks Amber Trails, Leila North, Riverbend, Rivergrove, Rosser - Old Kildonan, 51 West Kildonan Industrial Fogging will take place until 6:30 a.m. tomorrow. Daily public service announcements Public Service Announcements (PSAs) will be released daily at least eight hours in advance of planned fogging.