The 2019 RHA Indicators Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report DE Comments

Final Report July 24, 2013 BIKE TO WORK DAY FRIDAY, JUNE 21, 2013 FINAL REPORT Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 1 Final Report July 24, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................. page 2 a. Event Background 2 b. 2013 Highlights 4 2. Planning Process......................................... page 5 a. Steering Committee 5 b. Event Coordinator Hours 7 c. Volunteers 8 d. Planning Recommendations 8 3. Events............................................................ page 9 a. Countdown Events 9 b. Pit Stops 12 c. BBQ 15 d. Event Recommendations 17 4. Sponsorship................................................... page 18 a. Financial Sponsorship 18 b. In Kind Sponsorship 20 c. Prizes 23 d. Sponsorship Recommendations 24 5. Budget........................................................... page 25 6. Media & Promotions..................................... page 27 a. Media Conference 27 b. Website-biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 28 c. Enewsletter 28 d. Facebook 28 e. Twitter 29 f. Print & Digital Media 29 g. Media Recommendations 29 7. Design............................................................ page 31 a. Logo 31 b. Posters 31 c. T-shirts 32 d. Banners 32 e. Free Press Ad 33 f. Bus Boards 33 g. Handbills 34 h. Design Recommendations 34 8. T-shirts............................................................ page 35 a. T-shirt Recommendations 36 9. Cycling Counts............................................. page 37 10. Feedback & Recommendations............... page 41 11. Supporting Documents.............................. page 43 a. Critical Path 43 b. Media Release 48 c. Sample Sponsorship Package 50 d. Volunteer List 55 Created by: Andraea Sartison www.biketoworkdaywinnipeg.org 2 Final Report July 24, 2013 1. INTRODUCTION Winnipeg’s 6th Annual Bike to Work Day was held on Friday, June 21st, 2013. The event consisted of countdown events from June 17-21st, online registration, morning pit stops and an after work BBQ with free food and live music. -

Point Douglas (“The North End”) a Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and Their Children

Point Douglas (“The North End”) A Community Programs and Services Guidebook for Families and their Children North Point Douglas Point Lord Selkirk Park Dufferin Douglas William Whyte Burrows Central St. Johns Neighbourhoods Luxton Inkster-Faraday Robertson Mynarski South Point Douglas This guide is produced and maintained by the WRHA Point Douglas Community Health Office. For editing, revisions or other information regarding content, please contact Vince Sansregret @ 204-(801-7803) or email: [email protected] INDEX Community Leisure and Recreation Centres Page 2 City of Winnipeg Fee Subsidy Program Page 3 Public Computer Access sites Page 3 Licensed Child Care Facilities Page 4-5 Food Banks/Free Community Meal programs Page 6 Cooking Programs – Food Security Page 7 Discount Clothing, Furniture, Household items Page 8 Community Support Programs Page 9-11 Programs for Expecting Parents and Families with infants Page 12 Libraries / Family Literacy Page 13 Parent and Child/Parenting Support Programs Page 14-15 City of Winnipeg Priceless Fun FREE Programming Page 16 FREE Child/Youth Recreation/‘drop-in’ Programs Page 17-19 Adult Ed.-Career Preparation Programs Page 20-21 Community, Leisure and Recreation Centres Luxton Community Centre 210 St. Cross St. Win Gardner-North End Wellness Phone: 204- 582-8249 Center - YMCA 363 McGregor St. Norquay Community Centre Phone: 204-293-3910 65 Granville St. Phone: 204-943-6897 Turtle Island Neighbourhood Centre 510 King St Sinclair Park Community Phone: 204-986-8346 Centre 490 Sinclair Ave. William Whyte Neighbourhood Phone: 204-582-8257 Association – Pritchard Park Recreation Centre Ralph Brown Community 295 Pritchard Ave. Centre Phone: 204-582 – 0988 460 Andrews Street Phone: 204-586-3149 Sgt. -

Valid Operating Permits

Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality Region Number Facility 20525 WOODLANDS SHELL UST Woodlands Interlake 20532 TRAPPERS DOMO UST Alexander Eastern 55141 TRAPPERS DOMO AST Alexander Eastern 20534 LE DEPANNEUR UST La Broquerie Eastern 63370 LE DEPANNEUR AST La Broquerie Eastern 20539 ESSO - THE PAS UST The Pas Northwest 20540 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN UST Virden Western 20542 VALLEYVIEW CO-OP - VIRDEN AST Virden Western 20545 RAMERS CARWASH AND GAS UST Beausejour Eastern 20547 CLEARVIEW CO-OP - LA BROQUERIE GAS BAR UST La Broquerie Red River 20551 FEHRWAY FEEDS AST Ridgeville Red River 20554 DOAK'S PETROLEUM - The Pas AST Gillam Northeast 20556 NINETTE GAS SERVICE UST Ninette Western 20561 RW CONSUMER PRODUCTS AST Winnipeg Red River 20562 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 29143 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC AST Winnipeg Red River 42388 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 42390 BORLAND CONSTRUCTION INC JST Winnipeg Red River 20563 MISERICORDIA HEALTH CENTRE AST Winnipeg Red River 20564 SUN VALLEY CO-OP - 179 CARON ST UST St. Jean Baptiste Red River 20566 BOUNDARY CONSUMERS CO-OP - DELORAINE AST Deloraine Western 20570 LUNDAR CHICKEN CHEF & ESSO UST Lundar Interlake 20571 HIGHWAY 17 SERVICE UST Armstrong Interlake 20573 HILL-TOP GROCETERIA & GAS UST Elphinstone Western 20584 VIKING LODGE AST Cranberry Portage Northwest 20589 CITY OF BRANDON AST Brandon Western 1 Valid Petroleum Storage Permits (as of September 15, 2021) Permit Type of Business Name City/Municipality -

Go…To the Waterfront, Represents Winnipeg’S 20 Year Downtown Waterfront Vision

to the Waterfront DRAFT Go…to the Waterfront, represents Winnipeg’s 20 year downtown waterfront vision. It has been inspired by Our Winnipeg, the official development and sustainable 25-year vision for the entire city. This vision document for the to the downtown Winnipeg waterfront is completely aligned with the Complete Communities strategy of Our Winnipeg. Go…to the Waterfront provides Waterfront compelling ideas for completing existing communities by building on existing assets, including natural features such as the rivers, flora and fauna. Building upon the principles of Complete Communities, Go…to the Waterfront strives to strengthen and connect neighbourhoods with safe and accessible linear park systems and active transportation networks to each other and the downtown. The vision supports public transit to and within downtown and ensures that the river system is incorporated into the plan through all seasons. As a city for all seasons, active, healthy lifestyles 2 waterfront winnipeg... a 20 year vision draft are a focus by promoting a broad spectrum of “quality of life” infrastructure along the city’s opportunities for social engagement. Sustainability waterfront will be realized through the inclusion of COMPLETE COMMUNITIES is also a core principle, as the vision is based on economic development opportunities identified in the desire to manage our green corridors along this waterfront vision. A number of development our streets and riverbank, expand ecological opportunities are suggested, both private and networks and linkages and ensure public access public, including specific ideas for new businesses, to our riverbanks and forests. Finally, this vision infill residential projects, as well as commercial supports development: mixed use, waterfront living, and mixed use projects. -

Physician Directory

Physician Directory, Currently Practicing in the Province Information is accurate as of: 9/24/2021 8:00:12 AM Page 1 of 97 Name Office Address City Prov Postal Code CCFP Specialty Abara, Chukwuma Solomon Thompson Clinic, 50 Selkirk Avenue Thompson MB R8N 0M7 CCFP Abazid, Nizar Rizk Health Sciences Centre, Section of Neonatology, 665 William Avenue Winnipeg MB R3E 0L8 Abbott, Burton Bjorn Seven Oaks General Hospital, 2300 McPhillips Street Winnipeg MB R2V 3M3 CCFP Abbu, Ganesan Palani C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abbu, Kavithan Ganesan C.W. Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 CCFP Abdallateef, Yossra Virden Health Centre, 480 King Street, Box 400 Virden MB R0M 2C0 Abdelgadir, Ibrahim Mohamed Ali Manitoba Clinic, 790 Sherbrook Street Winnipeg MB R3A 1M3 Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology Abdelmalek, Abeer Kamal Ghobrial The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 Abdulrahman, Suleiman Yinka St. Boniface Hospital, Room M5038, 409 Tache Avenue Winnipeg MB R2H 2A6 Psychiatry Abdulrehman, Abdulhamid Suleman 200 Ste. Anne's Road Winnipeg MB R2M 3A1 Abej, Esmail Ahmad Abdullah Winnipeg Clinic, 425 St. Mary Ave Winnipeg MB R3C 0N2 CCFP Gastroenterology, Internal Medicine Abell, Margaret Elaine 134 First Street, Box 70 Wawanesa MB R0K 2G0 Abell, William Robert Rosser Avenue Medical Clinic, 841 Rosser Avenue Brandon MB R7A 0L1 Abidullah, Mohammad Westman Regional Laboratory, Rm 146 L, 150 McTavish Avenue Brandon MB R7A 7H8 Anatomical Pathology Abisheva, Gulniyaz Nurlanbekovna Pine Falls Health Complex, 37 Maple Street, Box 1500 Pine Falls MB R0E 1M0 CCFP Abo Alhayjaa, Sahar C W Wiebe Medical Centre, 385 Main Street Winkler MB R6W 1J2 Obstetrics & Gynecology Abou-Khamis, Rami Ahmad Northern Regional Health, 867 Thompson Drive South Thompson MB R8N 1Z4 Internal Medicine Aboulhoda, Alaa Samir The Pas Clinic, Box 240 The Pas MB R9A 1K4 General Surgery Abrams, Elissa Michele Meadowwood Medical Centre, 1555 St. -

Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization

Facilitating the Integration of Planning and Development for Downtown Revitalization: CentreVenture’s Involvement in the Redevelopment of Downtown Winnipeg by Elisabeth Saftiuk A practicum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of City Planning Department of City Planning University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2014 Elisabeth Saftiuk Abstract Downtowns contribute significantly to the economy of cities and as a result, decision makers are increasingly recognizing the fundamental value and importance of maintaining viable downtown cores. Following the post-war era of urban decay and suburban expansion, there have been widespread attempts nationwide to reverse trends and to revitalize downtowns. In the Winnipeg context, urban renewal was practiced throughout the 1960s and 1970s; tripartite agreements were utilized during the 1980s; and development corporations were introduced throughout the 1980s and 1990s as a way to encourage private sector investment with targeted public sector investments. This practicum investigates the relationship between planning and development in the downtown revitalization context. In particular, this research aims to discover the extent to which a downtown development agency may have facilitated the better integration of planning and development in a city’s downtown, where revitalization has been very much on the public agenda. Winnipeg’s CentreVenture Development Corporation was used as a case study to explore this relationship. It was established in 1999 and continues to operate today. This paper attempts to determine the extent of its involvement, and the manner by which this arms-length government agency has aided and influenced tangible development in Winnipeg’s downtown. -

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide

Citizenship Study Materials for Newcomers to Manitoba: Based on the 2011 Discover Canada Study Guide Table of Contents ____________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I TIPS FOR THE VOLUNTEER FACILITATOR II READINGS: 1. THE OATH OF CITIZENSHIP .........................................................................................1 2. WHO WE ARE ...............................................................................................................7 3. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 1) ...................................................................................13 4. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 2) ...................................................................................20 5. CANADA'S HISTORY (PART 3) ...................................................................................26 6. MODERN CANADA ....................................................................................................32 7. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 1) .............................................. 40 8. HOW CANADIANS GOVERN THEMSELVES (PART 2) .............................................. 45 9. ELECTIONS (PART 1) ................................................................................................. 50 10. ELECTIONS (PART 2) ...............................................................................................55 11. OTHER LEVELS OF GOVERNMENT IN CANADA ................................................... 60 12. HOW MUCH DO YOU KNOW ABOUT YOUR GOVERNMENT? .............................. -

A Critical Analysis of Childcare Waiting Lists in Winnipeg

The Waiting Game: A Critical Analysis of Childcare Waiting Lists in Winnipeg Michelle Albl A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2012 by Michelle Albl Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84962-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84962-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

April 2019 Availability Report

APRIL 2019 AVAILABILITY REPORT INDUSTRIAL OFFICE RETAIL LAND & INVESTMENT FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR LEASE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE www.cwstevenson.ca Independently Owned and Operated / A Member of the Cushman & Wakefield Alliance ©2018 Cushman & Wakefield. All rights reserved. The information contained in this communication is strictly confidential. This information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable but has not been verified. NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE CONDITION OF THE PROPERTY (OR PROPERTIES) REFERENCED HEREIN OR AS TO THE ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO ERRORS, OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITIONS, WITHDRAWAL WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY SPECIAL LISTING CONDITIONS IMPOSED BY THE PROPERTY OWNER(S). ANY PROJECTIONS, OPINIONS OR ESTIMATES ARE SUBJECT TO UNCERTAINTY AND DO NOT SIGNIFY CURRENT OR FUTURE PROPERTY PERFORMANCE. INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE www.cwstevenson.ca CUSHMAN & WAKEFIELD INDUSTRIAL FOR LEASE APRIL 2019 *Please click the property image for more details. CAM RENTAL & CONTACT ADDRESS ZONING UNIT/SUITE AREA AVAILABLE LOADING MAX CLR HT RATE TAX COMMENTS (SF +/-) GRADE DOCK (+/-) (PSF) (PSF) 26 BUNTING STREET TYSON PREISENTANZ M2 8,283 1 3 16' $7.50 $3.00 • Located in the heart of Inkster Industrial 204 928 5002 Park close to major trucking routes and many amenities • (+/-) 1,000 sf office build out • Great parking BROOKSIDE LOT 4 CHRIS MACSYMIC I2 6,750 - 39,875 24’ TBD TBD NEW STATE OF THE ART 204 928 5019 INDUSTRIAL BUILDING • Strategically located within CentrePort Canada TYSON PREISENTANZ • No city of Winnipeg business taxes 204 928 5002 • Direct access to CentrePort Canada Way and Route 90 in close proximity to the Winnipeg RYAN MUNT James A. -

Gentrification in West Broadway?

Gentrification in West Broadway? Contested Space in a Winnipeg Inner City Neighbourhood By Jim Silver ISBN 0-88627-463-x May 2006 About the Author Jim Silver is a Professor of Politics at the University of Winnipeg, and a member of the Board of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Acknowledgements For their various contributions to this project, I am grateful to Roger Barske, Nigel Basely, Ken Campbell, Paul Chorney, Matt Friesen, Linda Gould, Brian Grant, Rico John, Darren Lezubski, Jennifer Logan, John Loxley, Shauna MacKinnon, Brian Pannell, Boyd Poncelet, Bob Shere and Linda Williams. Thanks also to the University of Winnipeg for awarding a Major Research Grant that made research for this project possible. This report is available free of charge from the CCPA website at www.policyalternatives.ca. Printed copies may be ordered through the Manitoba Office for a $10 fee. CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES–MB 309-323 Portage Ave., Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3B 2C1 PHONE (204) 927-3200 FAX (204) 927-3201 EMAIL [email protected] www.policyalternatives.ca/mb Contents 5 Introduction 7 1 Gentrification: A Brief Review of the Literature 12 2 The West Broadway Neighbourhood 18 3 The Dangers of Gentrification 20 4 Evidence of Gentrification in West Broadway 25 5 Why is Gentrification Occurring in West Broadway? 28 6 The Importance of Low-Income Rental Housing for West Broadway’s Future 31 7 Prospects for West Broadway 33 References GENTRIFicATION in WEST BROADWAY? Contested Space in a Winnipeg Inner City Neighbourhood By Jim Silver Since the mid-20th century, urban decline has rehabilitation of deteriorated but architecturally become almost ubiquitous in North American unique housing, stabilization of the population inner city neighbourhoods. -

Standing Committee on Justice

Third Session – Forty-Second Legislature of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba Standing Committee on Justice Chairperson Mr. Andrew Micklefield Constituency of Rossmere Vol. LXXV No. 1 - 5:30 p.m., Monday, November 30, 2020 ISSN 1708-6671 MANITOBA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Forty-Second Legislature Member Constituency Political Affiliation ADAMS, Danielle Thompson NDP ALTOMARE, Nello Transcona NDP ASAGWARA, Uzoma Union Station NDP BRAR, Diljeet Burrows NDP BUSHIE, Ian Keewatinook NDP CLARKE, Eileen, Hon. Agassiz PC COX, Cathy, Hon. Kildonan-River East PC CULLEN, Cliff, Hon. Spruce Woods PC DRIEDGER, Myrna, Hon. Roblin PC EICHLER, Ralph, Hon. Lakeside PC EWASKO, Wayne Lac du Bonnet PC FIELDING, Scott, Hon. Kirkfield Park PC FONTAINE, Nahanni St. Johns NDP FRIESEN, Cameron, Hon. Morden-Winkler PC GERRARD, Jon, Hon. River Heights Lib. GOERTZEN, Kelvin, Hon. Steinbach PC GORDON, Audrey Southdale PC GUENTER, Josh Borderland PC GUILLEMARD, Sarah, Hon. Fort Richmond PC HELWER, Reg, Hon. Brandon West PC ISLEIFSON, Len Brandon East PC JOHNSON, Derek Interlake-Gimli PC JOHNSTON, Scott Assiniboia PC KINEW, Wab Fort Rouge NDP LAGASSÉ, Bob Dawson Trail PC LAGIMODIERE, Alan Selkirk PC LAMONT, Dougald St. Boniface Lib. LAMOUREUX, Cindy Tyndall Park Lib. LATHLIN, Amanda The Pas-Kameesak NDP LINDSEY, Tom Flin Flon NDP MALOWAY, Jim Elmwood NDP MARCELINO, Malaya Notre Dame NDP MARTIN, Shannon McPhillips PC MICHALESKI, Brad Dauphin PC MICKLEFIELD, Andrew Rossmere PC MORLEY-LECOMTE, Janice Seine River PC MOSES, Jamie St. Vital NDP NAYLOR, Lisa Wolseley NDP NESBITT, Greg Riding Mountain PC PALLISTER, Brian, Hon. Fort Whyte PC PEDERSEN, Blaine, Hon. Midland PC PIWNIUK, Doyle Turtle Mountain PC REYES, Jon Waverley PC SALA, Adrien St. -

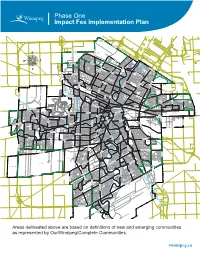

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST.