GOTHIC SERPENT Black Hawk Down Mogadishu 1993

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redmon Returns Inside This Edition

75¢ VOLUME 07 • NUMBER 23 PSALM 100:3 June 8, 2021 MORGAN COUNTY WEATHER THIS WEEK Moonshine & Mud Veteran of the Week Thomas P. Payne The weekend was packed full of great People came from all over to hole tournament, chili cookoff, bbq sauce things to do in Morgan County. One attend the event. Vendors, food, games, contest, and much more. of those was the Moonshine and Mud crafts, live music, and the Mud Sling were Johnboy says he is ready for next festival hosted by Johnboy’s BBQ at the all a part of the fun. years event to be a 2 day festival to pack Morgan County Fairgrounds. There was a mullet contest, corn- in all the fun. LEO of the Week The Badge Redmon Returns Inside This Edition Obits Page 2 Local Page 3 History Page 4 Games Page 5 Faith, Family Freedom Page 6 American Heritage Page 8 Heroes Page 9 Trending Page 10 After a short rest, Tom We are grateful Redmon has returned to to have him be a part of Like & Follow us writing. He took a short our paper but more im- on Social Media. break just to get some portantly a fixture in the rest but is back bringing Morgan County fabric. you the articles that you He is truly a treasure. enjoy so much. Tuesday, Page 2 In Loving Memory June 8, 2021 Loreen Bunch, 73 Jerry Dean Phillips, 54 Loreen Bunch, age 73 of Devo- Also surviving are several niec- Jerry Dean Phillips, age 54, of wife, Paulette Phillips of Coal- nia passed away at her home es, nephews and other friends Devonia passed away Sunday, field; nephews, Kevin Ward, on Saturday, May 29, 2021. -

Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (APO)

E-Book - 22. Checklist - Stamps of India Army Postal Covers (A.P.O) By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 22. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 8th May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 27 Nos. Date/Year Details of Issue 1 2 1971 - 1980 1 01/12/1954 International Control Commission - Indo-China 2 15/01/1962 United Nations Force - Congo 3 15/01/1965 United Nations Emergency Force - Gaza 4 15/01/1965 International Control Commission - Indo-China 5 02/10/1968 International Control Commission - Indo-China 6 15.01.1971 Army Day 7 01.04.1971 Air Force Day 8 01.04.1971 Army Educational Corps 9 04.12.1972 Navy Day 10 15.10.1973 The Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers 11 15.10.1973 Zojila Day, 7th Light Cavalary 12 08.12.1973 Army Service Corps 13 28.01.1974 Institution of Military Engineers, Corps of Engineers Day 14 16.05.1974 Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services 15 15.01.1975 Armed Forces School of Nursing 03.11.1976 Winners of PVC-1 : Maj. Somnath Sharma, PVC (1923-1947), 4th Bn. The Kumaon 16 Regiment 17 18.07.1977 Winners of PVC-2: CHM Piru Singh, PVC (1916 - 1948), 6th Bn, The Rajputana Rifles. 18 20.10.1977 Battle Honours of The Madras Sappers Head Quarters Madras Engineer Group & Centre 19 21.11.1977 The Parachute Regiment 20 06.02.1978 Winners of PVC-3: Nk. -

2019 Wisconsin Act 23

Date of enactment: November 19, 2019 2019 Assembly Bill 77 Date of publication*: November 20, 2019 2019 WISCONSIN ACT 23 AN ACT to create 84.10395 of the statutes; relating to: designating and marking STH 33 in Columbia County as the Staff Sergeant Daniel D. Busch Memorial Highway. The people of the state of Wisconsin, represented in ber 3, 1993, while serving as a member of Task Force senate and assembly, do enact as follows: Ranger during operations in support of United Nations SECTION 1. 84.10395 of the statutes is created to read: Operation in Somalia II in Mogadishu, Somalia. 84.10395 Staff Sergeant Daniel D. Busch Memo- (b) During Operation Gothic Serpent, when the rial Highway. (1) The department shall designate and, MH−60 helicopter he was in was shot down by enemy subject to sub. (2), mark the route of STH 33 commenc- fire, SSG Dan Busch immediately exited the aircraft, ing at the eastern border of the city of Portage and pro- took control of a key intersection, and provided suppres- ceeding westerly to the Columbia County line as the sive fire with his M249 automatic weapon against over- “Staff Sergeant Daniel D. Busch Memorial Highway” in whelming enemy forces, thus, protecting the lives of and honor and recognition of Staff Sergeant Daniel D. Busch. ensuring the survival of his fellow team members. It was (2) Upon receipt of sufficient contributions from during this battle that SSG Busch received his fatal interested parties, including any county, city, village, or wound and later died at a medical aid station. -

Vol 66 No 3: September 2014

www.gurkhabde.com/publication The magazine for Gurkha Soldiers and their Families PARBVolAT 66 No 3: SeptemberE 2014 Gurkha permanent staff with the World Marathon Champion Mr Kiprotich during the Bupa Great North Run 2014 ii PARBATE Vol 66 No 3 September 2014 PARBATE ENTERING A MODERN ERA HQ Bde of Gurkhas, FASC, Sandhurst, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ. All enquiries Tel: 01276412614 / 94261 2614 Fax: 0127641 2694 / 94261 2694 Email: [email protected] Editor Cpl Sagar Sherchan 0127641 2614 [email protected] Comms Officer Cpl Sagar Sherchan GSPS Mr Ken Pike 0127641 2776 [email protected] elcomeelcome to to a a brand brand new new edition edition with with lots lots of of changes changes Please send your articles together with high WWinin terms terms of of the the outline outline and and design. design. Lots Lots of of attractive attractive quality photographs (min 300dpi), through your unit’s Parbate Rep, to: subjectssubjects and and some some great great photographs photographs from from around around the the globe globe The Editor, Parbate Office, awaitawait our our readers. readers. HQBG, FASC, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ AsA soperations operations in in Afghanistan Afghanistan gradually gradually wind wind down, down, Parbate is published every month by kind permission soldierssoldiers from from 1 1 RGR RGR settled settled in in Brunei Brunei focusing focusing on on getting getting of HQBG. It is not an official publication and the views expressed, unless specifically stated otherwise, do backback the the basics basics right right (page (page 2). 2). not reflect MOD or Army policy and are the personal views of the author. -

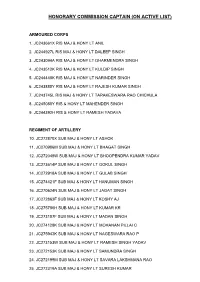

Honorary Commission Captain (On Active List)

HONORARY COMMISSION CAPTAIN (ON ACTIVE LIST) ARMOURED CORPS 1. JC243661X RIS MAJ & HONY LT ANIL 2. JC244927L RIS MAJ & HONY LT DALEEP SINGH 3. JC243094A RIS MAJ & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH 4. JC243512K RIS MAJ & HONY LT KULDIP SINGH 5. JC244448K RIS MAJ & HONY LT NARINDER SINGH 6. JC243880Y RIS MAJ & HONY LT RAJESH KUMAR SINGH 7. JC243745L RIS MAJ & HONY LT TARAKESWARA RAO CHICHULA 8. JC245080Y RIS & HONY LT MAHENDER SINGH 9. JC244392H RIS & HONY LT RAMESH YADAVA REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY 10. JC272870X SUB MAJ & HONY LT ASHOK 11. JC270906M SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHAGAT SINGH 12. JC272049W SUB MAJ & HONY LT BHOOPENDRA KUMAR YADAV 13. JC273614P SUB MAJ & HONY LT GOKUL SINGH 14. JC272918A SUB MAJ & HONY LT GULAB SINGH 15. JC274421F SUB MAJ & HONY LT HANUMAN SINGH 16. JC270624N SUB MAJ & HONY LT JAGAT SINGH 17. JC272863F SUB MAJ & HONY LT KOSHY AJ 18. JC275786H SUB MAJ & HONY LT KUMAR KR 19. JC273107F SUB MAJ & HONY LT MADAN SINGH 20. JC274128K SUB MAJ & HONY LT MOHANAN PILLAI C 21. JC275943K SUB MAJ & HONY LT NAGESWARA RAO P 22. JC273153W SUB MAJ & HONY LT RAMESH SINGH YADAV 23. JC272153K SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAMUNDRA SINGH 24. JC272199M SUB MAJ & HONY LT SAVARA LAKSHMANA RAO 25. JC272319A SUB MAJ & HONY LT SURESH KUMAR 26. JC273919P SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 27. JC271942K SUB MAJ & HONY LT VIRENDER SINGH 28. JC279081N SUB & HONY LT DHARMENDRA SINGH RATHORE 29. JC277689K SUB & HONY LT KAMBALA SREENIVASULU 30. JC277386P SUB & HONY LT PURUSHOTTAM PANDEY 31. JC279539M SUB & HONY LT RAMESH KUMAR SUBUDHI 32. -

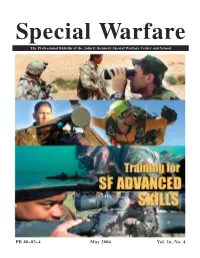

Analysis of Operation Gothic Serpent: TF Ranger in Somalia (Https:Asociweb.Soc.Mil/Swcs/Dotd/Sw-Mag/Sw-Mag.Htm)

Special Warfare The Professional Bulletin of the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School PB 80–03–4 May 2004 Vol. 16, No. 4 From the Commandant Special Warfare In recent years, the JFK Special Warfare Center and School has placed a great emphasis on the Special Forces training pipeline, and much of our activity has been concerned with recruiting, assessing and training Special Forces Soldiers to enter the fight against terrorism. Less well-publicized, but never- theless important, are our activi- ties devoted to training Special Forces Soldiers in advanced skills. These skills, such as mili- focus on a core curriculum of tary free-fall, underwater opera- unconventional warfare and tions, target interdiction and counterinsurgency, coupled with urban warfare, make our Soldiers advanced human interaction and more proficient in their close- close-quarters combat, has combat missions and better able proven to be on-the-mark against to infiltrate and exfiltrate with- the current threat. out being detected. Located at Fort Bragg, at Yuma Proving Ground, Ariz., and at Key West, Fla., the cadre of the 2nd Battal- ion, 1st Special Warfare Training Group provides such training. Major General Geoffrey C. Lambert Not surprisingly, the global war on terrorism has engendered greater demand for Soldiers with selected advanced skills. Despite funding constraints and short- ages of personnel, SWCS military and civilian personnel have been innovative and agile in respond- ing to the new requirements. The success of Special Forces Soldiers in the global war on ter- rorism has validated our training processes on a daily basis. Our PB 80–03–4 Contents May 2004 Special Warfare Vol. -

Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: a Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999

Document generated on 09/27/2021 3:15 p.m. Journal of Conflict Studies Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999. Stephen M. Grenier Volume 20, Number 1, Spring 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/jcs20_01br05 See table of contents Publisher(s) The University of New Brunswick ISSN 1198-8614 (print) 1715-5673 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grenier, S. M. (2000). Review of [Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999.] Journal of Conflict Studies, 20(1), 193–195. All rights reserved © Centre for Conflict Studies, UNB, 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Bowden, Mark.Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War.New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999. Mark Bowden's Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War is a dramatic, minute-by- minute account of the climatic battle in the unsuccessful campaign to end the human suffering in Somalia. The Battle of the Black Sea, as it is known, was the most intense fighting involving American troops since the Vietnam War, resulting in 18 American soldiers and over 500 Somalis killed. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-09-2 Volume 35 Number 2 April - June 2009

MIPB April - June 2009 PB 34-O9-2 Operations in OEF Afghanistan FROM THE EDITOR In this issue, three articles offer perspectives on operations in Afghanistan. Captain Nenchek dis- cusses the philosophy of the evolving insurgent “syndicates,” who are working together to resist the changes and ideas the Coalition Forces bring to Afghanistan. Captain Beall relates his experiences in employing Human Intelligence Collection Teams at the company level in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lieutenant Colonel Lawson provides a look into the balancing act U.S. Army chaplains as non-com- batants in Afghanistan are involved in with regards to Information Operations. Colonel Reyes discusses his experiences as the MNF-I C2 CIOC Chief, detailing the problems and solutions to streamlining the intelligence effort. First Lieutenant Winwood relates her experiences in integrating intelligence support into psychological operations. From a doctrinal standpoint, Lieutenant Colonels McDonough and Conway review the evolution of priority intelligence requirements from a combined operations/intelligence view. Mr. Jack Kem dis- cusses the constructs of assessment during operations–measures of effectiveness and measures of per- formance, common discussion threads in several articles in this issue. George Van Otten sheds light on a little known issue on our southern border, that of the illegal im- migration and smuggling activities which use the Tohono O’odham Reservation as a corridor and offers some solutions for combined agency involvement and training to stem the flow. Included in this issue is nomination information for the CSM Doug Russell Award as well as a biogra- phy of the 2009 winner. Our website is at https://icon.army.mil/ If your unit or agency would like to receive MIPB at no cost, please email [email protected] and include a physical address and quantity desired or call the Editor at 520.5358.0956/DSN 879.0956. -

Black Hawk Down

Black Hawk Down A Story of Modern War by Mark Bowden, 1951- Published: 1999 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Dedication & The Assault Black Hawk Down Overrun The Alamo N.S.D.Q. Epilogue Sources Acknowledgements J J J J J I I I I I For my mother, Rita Lois Bowden, and in memory of my father, Richard H. Bowden It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting the ultimate practitioner. Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian The Assault 1 At liftoff, Matt Eversmann said a Hail Mary. He was curled into a seat between two helicopter crew chiefs, the knees of his long legs up to his shoulders. Before him, jammed on both sides of the Black Hawk helicopter, was his „chalk,“ twelve young men in flak vests over tan desert camouflage fatigues. He knew their faces so well they were like brothers. The older guys on this crew, like Eversmann, a staff sergeant with five years in at age twenty-six, had lived and trained together for years. Some had come up together through basic training, jump school, and Ranger school. They had traveled the world, to Korea, Thailand, Central America … they knew each other better than most brothers did. They‘d been drunk together, gotten into fights, slept on forest floors, jumped out of airplanes, climbed mountains, shot down foaming rivers with their hearts in their throats, baked and frozen and starved together, passed countless bored hours, teased one another endlessly about girlfriends or lack of same, driven out in the middle of the night from Fort Benning to retrieve each other from some diner or strip club out on Victory Drive after getting drunk and falling asleep or pissing off some barkeep. -

8.16 Mogadishu PREVIEW

Nonfiction Article of the Week Table of Contents 8-16: The Battle of Mogadishu Terms of Use 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Activities, Difficulty Levels, Common Core Alignment, & TEKS 4 Digital Components/Google Classroom Guide 5 Teaching Guide, Rationale, Lesson Plans, Links, and Procedures: EVERYTHING 6-9 Article: The Battle of Mogadishu 10-11 *Modified Article: The Battle of Mogadishu 12-13 Activity 1: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Multiple Choice w/Key 14-15 Activity 2: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Open-Ended Questions w/Key 16-17 Activity 3: Text Evidence Activity w/Annotation Guide for Article 18-20 Activity 4: Text Evidence Activity & Answer Bank w/Key 21-23 Activity 5: Skill Focus – RI.8.7 Evaluate Mediums (Adv. and Disadv. of Each) 24-27 Activity 6: Integrate Sources –Video Clips & Questions w/Key 28-29 Activity 7: Skills Test Regular w/Key 30-33 Activity 8: Skills Test *Modified w/Key 34-37 ©2019 erin cobb imlovinlit.com Nonfiction Article of the Week Teacher’s Guide 8-16: The Battle of Mogadishu Activities, Difficulty Levels, and Common Core Alignment List of Activities & Standards Difficulty Level: *Easy **Moderate ***Challenge Activity 1: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Multiple Choice* RI.8.1 Activity 2: Basic Comprehension Quiz/Check – Open-Ended Questions* RI.8.1 Activity 3: Text Evidence Activity w/Annotation Guide for Article** RI.8.1 Activity 4: Text Evidence Activity w/Answer Bank** RI.8.1 Activity 5: Skill Focus – Evaluate Mediums*** RI.8.7 Activity 6: Integrate Sources – Video Clip*** RI.8.7, RL.8.7 Activity -

August 19, 1994

August 19, 1994 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 23285 The Women's Pre-Qualification Pilot Loan has received a technical assistance grant ORDERS FOR MONDAY, AUGUST 22, Program is designed to streamline the appli- from the American Indian Consultants, Inc., 1994 cation process and provide a quick response U.S. Department of Commerce, to provide to a non-profit intermediary for loan re- marketing services for Santa Fe Coat Com- Mr. SARBANES. Mr. President, on quests of $250,000 or less to women owned pany. behalf of the majority leader, I ask (51% or more) and managed businesses. It fo- Santa Fe Coat Company is an American In- unanimous consent that on Monday, cuses on the character. credit, experience dian owned apparel design, manufacturing following the prayer, the Journal of and reliability of the applicants. "During the and wholesaling business, located at Isleta proceedings be deemed approved to first few weeks that the pilot program has Pueblo, a village that lies 23 miles south of date and the time for the two leaders been in place our office has had many inquir- Albuquerque. New Mexico. Santa Fe Coat ies," Dowell states. "We hope to approve ad- reserved for their use later in the day; Company specializes in American Indian cus- that immediately thereafter, the Sen- ditional loans through this program and our tom designed women's coats, and its concept existing 7(a) guaranteed loan programs in is to produce Indian designed clothing from ate resume consideration of S. 2351, the the near future." drawing room to the finished product. Health Security Act.