Brookline COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2005–2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2007 Annual Report (PDF)

TOWN OF BROOKLINE MASSACHUSETTS 302nd Annual Report of the Town Officers of Brookline for the year ending December 31, 2007 townofbrooklinemass.com townofbrooklinemass.com Table of Contents Town Officers………………………………………………………...……………… 3 Selectmen…………………...……………………………………………………….. 9 Town Administrator………………………………………………………………… 17 Town Moderator..…………………………………………………………………… 24 Advisory Committee……………………………………………..…………………. 24 Town Meeting………………………………………..………...……………………. 27 General Government Town Clerk…………………………………………………………………... 39 Registrars of Voters………………………………………………………… 41 Town Counsel……………………………………………………………….. 42 Human Resources…………………………………………..……………… 43 Public Safety Police Department………………………………………………….………. 46 Fire Department…………………………………………………………….. 55 Building Department………………………………………………………... 58 Building Commission……………………………………………………….. 61 Board of Examiners………………………………………………………… 62 Public Works Administration Division……………………………………………………... 63 Highway and Sanitation Division………………………………………….. 67 Water and Sewer Division…………………………………………………. 71 Parks and Open Space Division…………………………………………... 74 Engineering and Transportation Division………………………………… 82 Recreation Department………………………………………...………………….. 90 Public Schools………………………………………..………...…………………… 93 Library………………………………………..………...………………………….…. 100 Planning and Community Development………………………………………... 104 Planning Division……………………………………………………………. 105 Preservation Division……………………………………………………….. 107 Housing Division……………………………………………………….. 109 Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) -

Brookline Compplan 0201.Qxd

Brookline Comprehensive Plan 2005–2015 Town of Brookline CREDITS BOARD OF SELECTMEN PLANNING BOARD Robert L. Allen, Jr., Chair Kenneth Goldstein, Chair Joseph T. Geller Mark Zarillo, Clerk Gilbert R. Hoy, Jr. Linda Hamlin Michael Merrill Stephen Heiken Michael S. Sher Jerome Kampler Richard Kelliher, Town Administrator COMPREHENSIVE PLAN COMMITTEE Joseph T. Geller, Co-Chair | Board of Selectman Robert L. Allen, Jr., Co-Chair | Board of Selectman Michael Berger | Advisory Committee, Town Meeting Member (TMM) Precinct 16 Dorothy Blom | Future Search/League of Women Voters of Brookline, TMM Precinct 10 Lawrence A. Chan | Citizen Suzanne de Monchaux | Future Search/League of Women Voters of Brookline Leslie Fabian | Brookline Housing Authority, TMM Precinct 11, Housing Advisory Board George Garfinkle | Preservation Commission Linda Hamlin | Planning Board Gary Jones | Board of Library Trustees, TMM Precinct 3 Jerry Katz | Chamber of Commerce Kevin Lang | School Committee, TMM Precinct 9 (former) Nancy Madden | Park & Recreation Commission, TMM Precinct 3 Shirley Radlo | Council on Aging, TMM Precinct 9 Michael Sandman | Transportation Board Roberta Schnoor | Conservation Commission, TMM Precinct 13 William L. Schwartz | Citizen, Transportation Board (former) Susan Senator | School Committee Martin Sokoloff | Citizen, Planning Board Member (former) Kathy A. Spiegelman | Housing Advisory Board Joanna Wexler | Conservation Commission (former), Greenspace Alliance Jim Zien | Economic Development Advisory Board FOCUS AREA WORK GROUPS MEMBERS Tony -

Hyde Park Bulletin

The Hyde Park Bulletin Volume 17, Issue 41 October 11, 2018 HPNA digs deeper into Neponset Greenway talks development issues bike paths in Hyde Park Members of the Hyde Park Neighborhood Association met and discussed the Railyard 5 Project, shown above, among other projects. COURTESY PHOTO Mary Ellen Gambon about 20-something units,” Staff Reporter HPNA president John Raymond said. “They tried to About 25 members of the confuse us by lowering the Hyde Park Neighborhood As- square footage by about 7,500 The Neponset River Greenway Council met last Wednesday and discussed its progress in Hyde Park. sociation attended the meeting square feet. But there wasn’t a PHOTO BY JEFF SULLIVAN on Thursday, October 4 to dis- big reduction in units.” cuss new development issues – The developer, Jordan D. one in the near future and the Jeff Sullivan bike lane on the streets and a na- project, which connected the Warshaw, of the Noannet ture bike path through protected Martini Shell to Mattapan be- other on the radar. Staff Reporter Group, eliminated 29 units areas of the Massachusetts De- tween the Truman Parkway and The first focus was a recap from the final plan. There will The Neponset River partment of Recreation and Con- the Neponset River. It opened in of the meeting on October 1 on be 364 for-rent apartments and Greenway Council (NRGC) met servation (DCR). Currently, there 2012 and was completed in the Sprague Street development 128 for-sale condos, according last week and discussed several are ways to bike the path, but some 2015, spanning to the Neponset project at 36-70 Sprague Street to the proposal. -

Time Line Map-Final

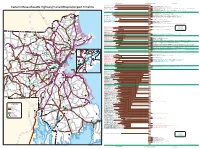

RAILROAD/TRANSIT HIGHWAY/BICYCLE/AIRPORT LEGISLATIVE Green Line to Medford (GLX), opened 2021 2021 2020 2019 Mass Central Rail Trail Wayside (Wayland, Weston), opened 2019 Silver Line SL3 to Chelsea, opened 2018 2018 Bruce Freeman Rail Trail Phase 2A (Westford, Carlise, Acton), opened 2018 Worcester CR line, Boston Landing Station opened 2017 2017 Eastern Massachusetts Highway/Transit/Bicycle/Airport Timeline Fitchburg CR line (Fitchburg–Wachusett), opened 2016 2016 MassPike tollbooths removed 2016 2015 Cochituate Rail Trail (Natick, Framingham), opened 2015, Upper Charles Rail Trail (Milford, Ashland, Holliston, Hopkinton), opened 2015, Watertown Greenway, opened 2015 Orange Line, Assembly Station opened 2014 2014 Veterans Memorial Trail (Mansfield), opened 2014 2013 Bay Colony Rail Trail (Needham), opened 2013 2012 Boston to Border South (Danvers Rail Trail), opened 2012, Northern Strand Community Trail (Everett, Malden, Revere, Saugus), opened 2012 2011 2010 Boston to Border Rail Trail (Newburyport, Salisbury), opened 2010 Massachusetts Department of TransportationEstablished 2009 Silver Line South Station, opened 2009 2009 Bruce Freeman Rail Trail Phase 1 (Lowell, Chelmsford Westford), opened 2009 2008 Independence Greenway (Peabody), opened 2008, Quequechan R. Bikeway (Fall River), opened 2008 Greenbush CR, reopened 2007 2007 East Boston Greenway, opened 2007 2006 Assabet River Rail Trail (Marlborough, Hudson, Stow, Maynard, Acton), opened 2006 North Station Superstation, opened 2005 2005 Blackstone Bikeway (Worcester, Millbury, Uxbridge, Blackstone, Millville), opened 2005, Depressed I-93 South, opened 2005 Silver Line Waterfront, opened 2004 2004 Elevated Central Artery dismantled, 2004 1 2003 Depressed I-93 North and I-90 Connector, opened 2003, Neponset River Greenway (Boston, Milton), opened 2003 Amesbury Silver Line Washington Street, opened 2002 2002 Leonard P. -

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA District 1964-Present

Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district 1964-2021 By Jonathan Belcher with thanks to Richard Barber and Thomas J. Humphrey Compilation of this data would not have been possible without the information and input provided by Mr. Barber and Mr. Humphrey. Sources of data used in compiling this information include public timetables, maps, newspaper articles, MBTA press releases, Department of Public Utilities records, and MBTA records. Thanks also to Tadd Anderson, Charles Bahne, Alan Castaline, George Chiasson, Bradley Clarke, Robert Hussey, Scott Moore, Edward Ramsdell, George Sanborn, David Sindel, James Teed, and George Zeiba for additional comments and information. Thomas J. Humphrey’s original 1974 research on the origin and development of the MBTA bus network is now available here and has been updated through August 2020: http://www.transithistory.org/roster/MBTABUSDEV.pdf August 29, 2021 Version Discussion of changes is broken down into seven sections: 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA 2) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Eastern Mass. St. Ry. Co. Norwood Area Quincy Area Lynn Area Melrose Area Lowell Area Lawrence Area Brockton Area 3) MBTA bus routes inherited from the Middlesex and Boston St. Ry. Co 4) MBTA bus routes inherited from Service Bus Lines and Brush Hill Transportation 5) MBTA bus routes initiated by the MBTA 1964-present ROLLSIGN 3 5b) Silver Line bus rapid transit service 6) Private carrier transit and commuter bus routes within or to the MBTA district 7) The Suburban Transportation (mini-bus) Program 8) Rail routes 4 ROLLSIGN Changes in MBTA Bus Routes 1964-present Section 1) MBTA bus routes inherited from the MTA The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) succeeded the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) on August 3, 1964. -

Section IV (Departmental Budgets) (PDF)

TOWN OF BROOKLINE PROGRAM GROUP: Administration and Finance FY2012 PROGRAM BUDGET PROGRAM: Selectmen PROGRAM DESCRIPTION FY2012 OBJECTIVES* The Board of Selectmen is composed of five members who are elected for staggered 1. To continue to observe policies and practices to ensure long-term financial three-year terms. As directors of the municipal corporation, they are vested with the sustainability, including: general management of the Town. The Selectmen initiate legislative policy by • the recommendations of the Override Study Committee, as adopted by inserting articles in Town Meeting Warrants and then implement and enforce the Resolution in March, 2008. votes subsequently adopted; establish town administrative policies; review and set • implementation of recommendations of the Efficiency Initiative Committee and OPEB Task Force, where feasible, and to explore new opportunities for fiscal guidelines for the annual operating budget and the six-year capital improvements program; appoint department heads and members of many official improving productivity and eliminating unnecessary costs. boards and commissions; hold public hearings on important town issues and periodic • Fiscal Policies relative to reserves and capital financing as part of the conferences with agencies under their jurisdiction and with community groups; ongoing effort to observe sound financial practices and retain the Aaa credit represent the Town before the General Court and in all regional and metropolitan rating. affairs; and enforce Town by-laws and regulations. • to continue to seek PILOT Agreements with institutional non-profits along with an equitable approach for community-based organizations. The Selectmen also serve as the licensing board responsible for issuing and • to continue to support the business community and vibrant commercial renewing over 600 licenses in 20 categories, including common victualler, food 2. -

270 Baker Street

Project Notification Form Submitted Pursuant to Article 80 of the Boston Zoning Code 270 BAKER STREET WEST ROXBURY, MASSACHUSETTS AUGUST 26, 2016 Submitted to: BOSTON REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY One City Hall Square Boston, MA 02201 Submitted by: 270 BAKER, LLC Prepared by: NORTHEAST STRATEGY AND COMMUNICATIONS GROUP Thomas Maistros, Jr., RA In Association with: NESHAMKIN FRENCH ARCHITECTS, INC. MCCLURG TRAFFIC . TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 PROJECT SUMMARY 1-1 1.1 Project Team 1-1 1.2 Project Description 1-2 1.3 Consistency with Zoning 1-6 1.4 Legal Information 1-7 1.5 Public Agencies 1-7 1.6 Schedule 1-8 1.7 Existing Photograph 1-9 2.0 ASSESSMENT OF DEVELOPMENT REVIEW COMPONENTS 2-1 2.1 Project Design 2-1 2.2 Urban Design 2-2 2.3 Design Exhibits 2-4 2.4 Historic Resources 2-14 2.5 Sustainable Design 2-19 2.6 Transportation 2-26 2.7 Environmental Protection 2-54 2.7.1 Wind 2-54 2.7.2 Shadow 2-54 2.7.3 Daylight 2-59 2.7.4 Solar Glare 2-62 2.7.5 Air Quality 2-62 2.7.6 Water Quality/Stormwater 2-63 2.7.7 Storm Water Management Standards 2-63 2.7.8 Flood Hazard Zones/Wetlands 2-63 2.7.9 Geotechnical/Groundwater 2-63 2.7.10 Solid and Hazardous Wastes 2-64 2.7.11 Noise/Vibration 2-65 2.7.12 Construction Impacts 2-66 2.7.13 Rodent Control 2-66 2.7.14 Wildlife Habitat 2.67 2.8 Infrastructure System 2-67 2.8.1 Sewage System 2-87 2.8.2 Water Supply System 3-68 2.8.3 Stormwater System 2-69 2.8.4 Energy Needs 2-72 3.0 COORDINATION WITH OTHER GOVERNMENTAL AGENCIES 3-1 4.0 PROJECT'S CERTIFICATION 4-1 APPENDICES Appendix A - Climate Change Checklist Appendix B - Accessibility Checklist Appendix C - Discclosure Statement 2016/270 Baker/Expanded PNF Page ii Table of Contents 1.0 PROJECT SUMMARY 1.1 Project Team Project Name: 270 Baker Street Location: The Project site is located at 270 Baker Street in the West Roxbury Neighborhood of the City of Boston. -

Following Boston's Mysterious Stony Brook

Following Boston's Mysterious Stony Brook Saturday, April 15, 2017 at 9:30 am at Adams Park in Roslindale Square 10:00 am at gate on Bellevue Hill Rd. in West Roxbury Starting from the city's highest point, Bellevue Hill, the stream known as Stony Brook goes through Stony Brook Reservation, Hyde Park, Roslindale, Jamaica Plain (including its Stonybrook neighborhood), Mission Hill, Roxbury, and the Fenway on its way to the Charles River. But it's almost all underground! Join Jessica Mink, whose house abuts the creek's conduit, on this bike ride to see how close we can come to its route. The group will return following the Muddy River and Bussey Brook. Look for pictures at http://www.masspaths.net/rides/StonyBrook2017.html Miles Action Miles Action 0.0 Start at Adams Park in Roslindale 7.7 Left on Bourne St. 0.0 Left on South St. 7.7 Left on Catherine St. 0.1 Straight under railroad tracks 7.8 Right on Wachusett St. 0.2 Left on Conway St. 8.0 Left on Southbourne St. 0.2 Straight across Robert St. 8.1 Right on Hyde Park Ave. 0.3 Straight on park path 8.7 Left on Ukraine Way 0.4 Left through tunnel under tracks 8.7 Right on Washington St. 0.5 Straight on Metcalf Ave. across Belgrade Ave. 9.0 Right on sidewalk after crossing the Arborway 0.5 Left on Haslet St. 9.0 Left on Southwest Corridor bike path 0.6 Right on Roslindale Ave. 10.6 Cross Centre St. -

Annual Report of the Metropolitan District Commission

Public Document No. 48 W$t Commontoealtfj of iWa&sacfmsfetta ANNUAL REPORT OF THE Metropolitan District Commission For the Year 1935 Publication or this Document Approved by the Commission on Administration and Finance lm-5-36. No. 7789 CONTENTS PAGE I. Organization and Administration . Commission, Officers and Employees . II. General Financial Statement .... III. Parks Division—Construction Wellington Bridge Nonantum Road Chickatawbut Road Havey Beach and Bathhouse Garage Nahant Beach Playground .... Reconstruction of Parkways and Boulevards Bridge Repairs Ice Breaking in Charles River Lower Basin Traffic Control Signals IV. Maintenance of Parks and Reservations Revere Beach Division .... Middlesex Fells Division Charles River Lower Basin Division . Bunker Hill Monument .... Charles River Upper Division Riverside Recreation Grounds . Blue Hills Division Nantasket Beach Reservation Miscellaneous Bath Houses Band Concerts Civilian Conservation Corps Federal Emergency Relief Activities . Public Works Administration Cooperation with the Municipalities . Snow Removal V. Special Investigations VI. Police Department VII. Metropolitan Water District and Works Construction Northern High Service Pipe Lines . Reinforcement of Low Service Pipe Lines Improvements for Belmont, Watertown and Arlington Maintenance Precipitation and Yield of Watersheds Storage Reservoirs .... Wachusett Reservoir . Sudbury Reservoir Framingham Reservoir, No. 3 Ashland, Hopkinton and Whitehall Reservoirs and South Sud- bury Pipe Lines and Pumping Station Framingham Reservoirs Nos. 1 and 2 and Farm Pond Lake Cochituate . Aqueducts Protection of the Water Supply Clinton Sewage Disposal Works Forestry Hydroelectric Service Wachusett Station . Sudbury Station Distribution Pumping Station Distribution Reservoirs . Distribution Pipe Lines . T) 11 P.D. 48 PAGE Consumption of Water . 30 Water from Metropolitan Water Works Sources used Outside of the Metropolitan Water District VIII. -

Report of the Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners (1898)

A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/reportofboardofm00mass_4 PUBLIC DOCUMENT No. 48. REPORT ~ Board of Metropolitan Park Commissioners. J^ANUARY, 1899. BOSTON : W RIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Square. 1899. A CONTENTS. PAGE Report of the Commissioners, 5 Report of the Secretary, 18 Report of the Landscape Architects, 47 Report of the Engineer, 64 Financial Statement, . 86 Analysis of Payments, 99 Claims (chapter 366 of the Acts of 1898), 118 KEPOKT. The Metropolitan Park Commission presents herewith its sixth annual report. At the presentation of its last report the Board was preparing to continue the acquirement of the banks of Charles River, and was engaged in the investigation of avail- able shore frontages and of certain proposed boulevards. Towards the close of its last session the Legislature made an appropriation of $1,000,000 as an addition to the Metropolitan Parks Loan, but further takings were de- layed until the uncertainties of war were clearly passed. Acquirements of land and restrictions have been made or provided for however along Charles River as far as Hemlock Gorge, so that the banks for 19 miles, except where occu- pied by great manufacturing concerns, are in the control either of this Board or of some other public or quasi public body. A noble gift of about 700 acres of woods and beau- tiful intervales south of Blue Hills and almost surroundingr Ponkapog Pond has been accepted under the will of the late ' Henry L. Pierce. A field in Cambridge at the rear of « Elm- wood," bought as a memorial to James Russell Lowell, has been transferred to the care of this Board, one-third of the purchase price having been paid by the Commonwealth and the remaining two-thirds by popular subscription, and will be available if desired as part of a parkway from Charles River to Fresh Pond. -

Other Public Transportation

Other Public Transportation SCM Community Transportation Massachusetts Bay Transportation (Cost varies) Real-Time Authority (MBTA) Basic Information Fitchburg Commuter Rail at Porter Sq Door2Door transportation programs give senior Transit ($2 to $11/ride, passes available) citizens and persons with disabilities a way to be Customer Service/Travel Info: 617/222-3200 Goes to: North Station, Belmont Town Center, mobile. It offers free rides for medical dial-a-ride, Information NEXT BUS IN 2.5mins Phone: 800/392-6100 (TTY): 617/222-5146 Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation grocery shopping, and Council on Aging meal sites. No more standing at (Waltham), Mass Audubon Drumlin Farm Wildlife Check website for eligibility requirements. a bus stop wondering Local bus fares: $1.50 with CharlieCard Sanctuary (Lincoln), Codman House (Lincoln), Rindge Ave scmtransportation.org when the next bus will $2.00 with CharlieTicket Concord Town Center Central Sq or cash on-board arrive. The T has more Connections: Red Line at Porter The Ride Arriving in: 2.5 min MBTA Subway fares: $2.00 with CharlieCard 7 min mbta.com/schedules_and_maps/rail/lines/?route=FITCHBRG The Ride provides door-to-door paratransit service for than 45 downloadable 16 min $2.50 with CharlieTicket Other Commuter Rail service is available from eligible customers who cannot use subways, buses, or real-time information Link passes (unlimited North and South stations to Singing Beach, Salem, trains due to a physical, mental, or cognitive disability. apps for smartphones, subway & local bus): $11.00 for 1 day $4 for ADA territory and $5 for premium territory. Gloucester, Providence, etc. -

Ffys 2020-24 TIP Massdot Project Comparison

FFYs 2020‐24 DRAFT TIP Programming (MassDOT Projects Only): Boston Region MPO Changes from FFYs 2019‐23 TIP 3/28/2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024 Current Proposed Current Proposed Current Proposed Current Proposed Proposed Earmark or Discretionary Grant 606501 ‐ Holbrook ‐ No Change Reconstruction of Union Street (Route 139), from Linfield Street to Centre Street/Water Street Bridge Program / Off‐System 608637 ‐ Maynard ‐ Bridge No Change 608255 ‐ [NEW] ‐ Stow ‐ Bridge TBD ‐ [NEW] ‐ Canton ‐ Bridge Replacement, M‐10‐006, Carrying Replacement, S‐29‐011, Box Mill Replacement, C‐02‐042, Revere Florida Road Over the Assabet Road Over Elizabeth Brook Court Over East Branch Neponset River River 608079 ‐ [MOVED FROM 2019] ‐ TBD ‐ [NEW] ‐ Hamilton ‐ Bridge Sharon ‐ Bridge Replacement, S‐ Replacement, Winthrop Street 09‐003 (40N), Moskwonikut Street Over Ipswich River Over AMTRAK/MBTA Bridge Program / On‐System (NHS) 605342 ‐ Stow ‐ Bridge No Change 604173 ‐ Boston ‐ Bridge Change in Cost Schedule 604173 ‐ Boston ‐ Bridge Change in Cost Schedule 606902 ‐ Boston ‐ Bridge No Change 608703 ‐ [NEW] ‐ Wilmington ‐ Replacement, S‐29‐001, (ST Replacement, B‐16‐016, North Replacement, B‐16‐016, North Reconstructure/Rehab, B‐16‐181, Bridge Replacement, W‐38‐029 62), Gleasondale Road Over the Washington Street Over the Washington Street Over the West Roxbury Parkway Over MBTA (2KV), ST 129 Lowell Street Over I‐ Assabet River Boston Inner Harbor Boston Inner Harbor 93 604173 ‐ Boston ‐ Bridge Cost Increase 605287 ‐ Chelsea ‐ Route 1 No Change 608614 ‐ Boston