The Penny Papers: Imagining Margaret Penny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sketch of the Life and Writings of Robert Knox, the Anatomist

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com ASketchoftheLifeandWritingsRobertKnox,Anatomist HenryLonsdale V ROBERT KNOX. t Zs 2>. CS^jC<^7s><7 A SKETCH LIFE AND WRITINGS ROBERT KNOX THE ANA TOM/ST. His Pupil and Colleague, HENRY LONSDALE. ITmtfora : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1870. / *All Rights reserve'*.] LONDON : R. CLAV, SONS, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. TO SIR WILLIAM FERGUSSON, Bart. F.R.S., SERJEANT-SURGEON TO THE QUEEN, AND PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF SURGEONS OF ENGLAND. MY DEAR FERGUSSON, I have very sincere pleasure in dedicating this volume to you, the favoured pupil, the zealous colleague, and attached friend of Dr. Robert Knox. In associating your excellent name with this Biography, I do honour to the memory of our Anatomical Teacher. I also gladly avail myself of this opportunity of paying a grateful tribute to our long and cordial friendship. Heartily rejoicing in your well-merited position as one of the leading representatives of British Surgery, I am, Ever yours faithfully, HENRY LONSDALE. Rose Hill, Carlisle, September 15, 1870. PREFACE. Shortly after the decease of Dr. Robert Knox (Dec. 1862), several friends solicited me to write his Life, but I respectfully declined, on the grounds that I had no literary experience, and that there were other pupils and associates of the Anatomist senior to myself, and much more competent to undertake his biography : moreover, I was borne down at the time by a domestic sorrow so trying that the seven years since elapsing have not entirely effaced its influence. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

Eric L. Mills H.M.S. CHALLENGER, HALIFAX, and the REVEREND

529 THE DALHOUSIE REVIEW Eric L. Mills H.M.S. CHALLENGER, HALIFAX, AND THE REVEREND DR. HONEYMAN I The arrival of the British corvette Challenger in Halifax on May 9, 18 7~l. was not particularly unusual in itself. But the men on board and the purpose of the voyage were unusual, because the ship as she docked brought oceanography for the first time to Nova Scotia, and in fact was establishing that branch of science as a global, coherent discipline. The arrival of Challenger at Halifax was nearly an accident. At its previous stop, Bermuda, the ship's captain, G.S. Nares, had been warned that his next port of call, New York, was offering high wages and that he could expect many desertions. 1 Course was changed; the United States coast passed b y the port side, and Challenger steamed slowly into the early spring of Halifax Harbour. We reached Halifax on the morning of the 9th. The weather was very fine and perfectly still, w :i th a light mist, and as we steamed up the bay there was a most extraordinary and bewildering display of mirage. The sea and the land and the sky were hopelessly confused; all the objects along the shore drawn up out of all proportion, the white cottages standing out like pillars and light-house!:, and all the low rocky islands loo king as if they were crowned with battlements and towers. Low, hazy islands which had no place on the chart bounded the horizon, and faded away while one was looking at them. -

And Physicians of Southern Alberta

Medical Clinics and Physicians of Southern Alberta Gerald M. McDougall & Fiona C. Harris ~ ~ N RA 983 .A4 105 A424 1991 C.2 Medical Clinics and Physicians of Southern Alberta Gerald M. McDougall & Fiona C. Harris with Jim Middlemiss Leopold Lewis & D.S. Grant © 1991 by Gerald M. McDougall. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by print, photocopy, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data: McDougall, Gerald M. (Gerald Millward), 1934- Medical clinics and physicians of Southern Alberta Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-83953-162-5 1. Group medical practice--Alberta--History. 2. Clinics--Alberta--History. I. Harris, Fiona C. II. Title. RA983.A4A46 1992 610'.65'09712309 C92-091727-5 Published by: G. M. McDougall 3707 Utah Drive N.W. Calgary, Alberta T2N 4A6 Printed in Canada, by the University of Calgary Printing Services. This book is dedicated to: Donald R. Wilson, MD FRCPC Professor of Medicine, University of Alberta. Edward L. Margetts, MD FRCPC Professor of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia. physicians who as clinicians, teachers, medical historians and friends had a great influence on my life, and my interest in medical education and medical history. GMMcD. FOREWORD I was asked to read the manuscript of this book in the fall of 1989. Having read Teachers of Medicine, wherein one of the present editors coordinated the work of many of the early medical educators in tracing the development of grad uate clinical education in Calgary, I was pleased to examine this new work. -

A Selection of Books, Maps and Manuscripts on the Northwest Passage in the British Library

A selection of books, maps and manuscripts on the Northwest Passage in the British Library Early approaches John Cabot (1425-c1500 and Sebastian Cabot (1474-1557) "A brief somme of Geographia" includes description of a voyage made by Roger Barlow and Henry Latimer for Robert Thorne in company with Sebastian Cabot in 1526-1527. The notes on a Northern passage at the end are practically a repetition of what Thorne had advocated to the King in 1527. BL: Royal 18 B XXVIII [Manuscripts] "A note of S. Gabotes voyage of discoverie taken out of an old chronicle" / written by Robert Fabyan. In: Divers voyages touching the discouerie of America / R. H. [i.e. Richard Hakluyt]. London, 1582. BL: C.21.b.35 Between the title and signature A of this volume there are five leaves containing "The names of certaine late travaylers"etc., "A very late and great probabilitie of a passage by the Northwest part of America" and "An epistle dedicatorie ... to Master Phillip Sidney Esquire" Another copy with maps is at BL: G.6532 A memoir of Sebastian Cabot; with a review of the history of maritime discovery / [by Richard Biddle]; illustrated by documents from the Rolls, now first published. London: Hurst, Chance, 1831. 333p BL: 1202.k.9 Another copy is at BL: G.1930 and other editions include Philadelphia, 1831 at BL: 10408.f.21 and Philadelphia 1915 (with a portrait of Cabot) at BL: 10408.o.23 The remarkable life, adventures, and discoveries of Sebastian Cabot / J. F. Nicholls. London: Sampson, Low and Marston, 1869. -

Flesh on the Bones

FIFE FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNAL NEW SERIES No 34 Summer 2015 CONTENTS Contents,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,1 Editorial,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.,,,2 Flesh On The Bones,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,3 Crail Fishing Disaster,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,31 Miss Betty Stott,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,32 The Fife Family History Society,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,33 Waterloo,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,..,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,.34 Shorts,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,36 The Fife Gravestones Conference,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,39 The End of An Era,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,; ,,,,,,,,,,,,,40 Buffalo Bill in Kirkcaldy. ByTom Cunningham,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,42 John Goodsir. A Scottish Anatomist and Pioneer. By Michael Tracy,,,,,,,,,,,,,44 Chairman`s Report: AGM, 9 June 2015,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,62 Fife Family History Society: Accounts, 2014-15,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,64 -

Superman's Origin Story < Donald Sutherland As

3-month TV calendar Page 29 RETURNING FAVORITES WESTWORLD ELEMENTARY QUANTICO THE AMERICANS NEW GIRL She’s back. Still fearless. And still very, very funny! MUST-SEE NEW SHOWS MARCH 19–APRIL 1, 2018 Superman’s origin story DOUBLE ISSUE < Donald Sutherland as the world’s richest man Grey’s Anatomy spinoff DOUBLE ISSUE • 2 WEEKS OF LISTINGS VOLUME 66 | NUMBER 12 | ISSUE #3427–3428 In This Issue On the Cover 18 Cover Story: Roseanne The iconic family comedy is back! We check in to see what’s next for the Conner clan in ABC’s much-anticipated reboot. 22 Spring Preview Donald Sutherland stars in FX’s Trust, Zach Braff returns with Alex, Inc., Superman’s history is told in Krypton, inside Grey’s Anatomy spinoff Station 19 (Jason George, inset) and Sandra Oh faces danger in Killing Eve. Plus: Intel on Westworld, The Americans, Quantico, Elementary, The Handmaid’s Tale and New Girl. 29 Spring TV Calendar 2 Ask Matt EDITOR’S 3 Stu We Love 4 Burning Questions LETTER Yikes! What really happened on that It’s been three decades since we met the shocking Bachelor finale. 5 Ratings Conners, a working-class family from fictional Lanford, Illinois, headed up by parents Rose- 6 Crime Scene NEW! anne, a factory line worker, and Dan, a contrac- Five can’t-miss specials and shows for true-crime fans. tor. Few shows since the ’70s had focused on 8 Tastemakers characters struggling with the money prob- Valerie Bertinelli dishes on her Food Network show. Plus: Her savory lems that come with blue-collar jobs. -

Franklin's Lost Ship: the Historic Discover of H.M.S. Erebus, by John Geiger and Alanna Mitchell

108 • REVIEWS FRANKLIN’S LOST SHIP: THE HISTORIC Otter, Harris and his dive team were able to make further DISCOVERY OF H.M.S. EREBUS. By JOHN GEIGER and dives on the wreck via a hole cut in the ice. They were able ALANNA MITCHELL. Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers to take a further series of spectacular photos of the wreck Ltd. ISBN 978-1-44344-417-0. 201 p., maps, b&w and to raise one of the ship’s brass six-pounder cannons. and colour illus., endnotes, bibliography. Hardbound. Geiger and Mitchell describe the exciting events of the Cdn$39.99. 2014 expedition in considerable detail, and their text is accompanied by spectacular photos of the wreck and of On 19 May 1845, HMS Erebus and Terror sailed from the Arctic landscape. Having no expertise in the techni- London under the command of Sir John Franklin, with the cal aspects of the underwater search, this reviewer has to aim of completing the first transit of the Northwest Passage assume that the descriptions of the search are accurate. The from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. On 17 September various stages of the search and the dives are covered in 2014, underwater archeologists Ryan Harris and Jonathan chapters that alternate with chapters on the history of Sir Moore of Parks Canada dived on the wreck of HMS Ere- John Franklin, his final voyage, and the extensive searches bus, to find it sitting almost upright and surprisingly intact that were subsequently mounted for the missing ships. in only 11 m of water in Queen Maud Gulf, in the general Unfortunately these chapters are strewn with errors, which area where Inuit traditional accounts maintain that the ship greatly lower the value of the book as a historical source. -

Kekerten Territorial Park

Nunavut Parks & Special Places – Editorial Series January, 2008 KEKERTEN TERRITORIAL PARK It’s the late 1830s, and whaling ships from England Penny searches southward along the coast of and America ply the waters of Lancaster Sound, Baffin Island for the fabled bay. Finding a large Baffin Bay, and Davis Strait, hunting the great bay opening to the west, he sails into the bay, past bowhead whales, rendering their blubber into oil numerous beautiful fiords. Whales are everywhere, and shipping it back to England. Each year the rolling, breaching, and spy-hopping. Seals bob arctic exacts a tremendous price – ships are crushed in the sparkling waters and seabirds dart over by ice or crews are trapped and forced to overwinter the waves. This may be the sanctuary he has been without proper supplies. Captain William Penny seeking, an ideal spot for the crews to spend the has an idea – if a place could be found where the winter. Penny anchors his ship off three small ships could be frozen in and where crews could live islands at the mouth of a deep fiord. The rest is on land during the winter, they could start the hunt history. much earlier in the spring, hunting along the floe Today, the area is called Cumberland Sound – edge, getting whales in a shorter time so they could and it played a huge role in North American return to England earlier, and rich. whaling history. As stocks elsewhere were The Inuit speak of a large bay that teems with depleted, there was more and more focus on this whales, seals, and fish, calling it Tenudiackbik… inlet, with its rich marine life that attracted the Aided by his Inuit shipmate, Eenoolooapik, baleen whales. -

Zoonoses in This Edition

Winter 2013 -14 The GeographerThe newsletter of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society Zoonoses In This Edition... Reservoirs, reasons and the role of viruses • RSGS’s First ‘Explorer-in- Residence’ • Zoonotic Geographies – A Multi-Faceted Issue • Viruses, Evolution & Spillover • Living Patterns, Vaccines & Vermin • A Syrian Refugee Camp & The Philippines After Haiyan • Villages of Hope • RSGS Education – A Year of Success! • Reader Offer: Life: A Journey Through Time “Intrepid disease ecologists are hiking into forests, climbing through caves,… and sleuthing the mysteries of reservoir host and spillover.” plus other news, David Quammen comments, books... RSGS: helping to make the connections between people, places & the planet The Geographerzoonoses oonoses are much more than just a good Tivy Education Medal word in Scrabble: the term derives from Alan Parkinson was awarded the Tivy Education Medal, together Z‘zoo’ meaning ‘of animals’, and the Greek with Fellowship of the RSGS, at the ‘nosos’ meaning ‘disease’, and refers to those Scottish Association of Geography diseases which can be passed from animals to Teachers conference in Perth in October. The award was given in humans. Many people anticipate that if there is to recognition of his work developing be a major outbreak of a new disease, it will most online educational resources for RSGS President Prof Iain Stewart presents the Medal to Alan Parkinson. likely be a zoonosis. schoolteachers. In 2001, Alan developed the then-revolutionary About 60% of current infectious diseases are thought to be Geography Pages website. He went on to become a zoonotic in origin. For example, all influenza stems from diseases prolific blogger, better known to some for his online of water birds such as ducks; even swine flu comes from birds, but persona ‘GeoBlogs’, and he now runs eight blogs on its appearance in pigs simply increased the likelihood of ‘spillover’ various aspects of geographical education. -

A Family Skeleton? Solving the Mystery of a Naval Surgeon on the Franklin Expedition

Topics in the History of Medicine. 2021; Volume 1: 25-38. A Family Skeleton? Solving the Mystery of a Naval Surgeon on the Franklin Expedition Iain Macintyre Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Nicolson Street, Edinburgh EH8 9DW, UK. Email: [email protected] Abstract Sharing a family history online led to an apparent connection with Harry Goodsir, a Scottish doctor, museum curator and naturalist who had served as an Assistant Surgeon on the Franklin Expedition to find the North-West Passage. Many years after the disappearance of the expedition, searchers on King William Island in the Canadian Arctic were taken by local Inuit to a skeleton which was repatriated and identified as that of Lieutenant Le Vesconte, an officer on the expedition. Buried under the Franklin Memorial at Greenwich, the skeleton was re-examined in 2009 when the memorial was moved. The results of that examination suggested that the skeleton might be that of Harry Goodsir. Keywords Harry Goodsir, surgeon, naturalist, Franklin Expedition, skeletal remains Introduction Researching family history has becoming an increasingly popular hobby, made much easier in recent years by the digitisation of registration and census documents and their ready availability on the internet. After creating a family tree, the author shared this on the Ancestry website where the contributions of other researchers resulted in finding many previously unknown ancestors. This is an account of one such forebear, Harry Goodsir (1819-c1848), an assistant surgeon on the 1845 Franklin Expedition to find the North-West Passage. A Family Skeleton? Mystery of a Naval Surgeon on the Franklin Expedition (Macintyre) A family tree The contact which resulted in the present story came from Michael Tracy in the United States. -

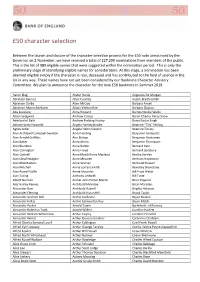

50 Character Selection

£50 character selection Between the launch and closure of the character selection process for the £50 note announced by the Governor on 2 November, we have received a total of 227,299 nominations from members of the public. This is the list of 989 eligible names that were suggested within the nomination period. This is only the preliminary stage of identifying eligible names for consideration: At this stage, a nomination has been deemed eligible simply if the character is real, deceased and has contributed to the field of science in the UK in any way. These names have not yet been considered by our Banknote Character Advisory Committee. We plan to announce the character for the new £50 banknote in Summer 2019. Aaron Klug Alister Hardy Augustus De Morgan Abraham Bennet Allen Coombs Austin Bradford Hill Abraham Darby Allen McClay Barbara Ansell Abraham Manie Adelstein Alliott Verdon Roe Barbara Clayton Ada Lovelace Alma Howard Barnes Neville Wallis Adam Sedgwick Andrew Crosse Baron Charles Percy Snow Aderlard of Bath Andrew Fielding Huxley Bawa Kartar Singh Adrian Hardy Haworth Angela Hartley Brodie Beatrice "Tilly" Shilling Agnes Arber Angela Helen Clayton Beatrice Tinsley Alan Archibald Campbell‐Swinton Anita Harding Benjamin Gompertz Alan Arnold Griffiths Ann Bishop Benjamin Huntsman Alan Baker Anna Atkins Benjamin Thompson Alan Blumlein Anna Bidder Bernard Katz Alan Carrington Anna Freud Bernard Spilsbury Alan Cottrell Anna MacGillivray Macleod Bertha Swirles Alan Lloyd Hodgkin Anne McLaren Bertram Hopkinson Alan MacMasters Anne Warner