A Preliminary Survey of Some Uralic Elements in Costanoan, Esselen, Chimariko and Salinan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

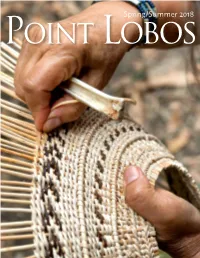

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Contents Abbreviations of the Names of Languages in the Statistical Maps

V Contents Abbreviations of the names of languages in the statistical maps. xiii Abbreviations in the text. xv Foreword 17 1. Introduction: the objectives 19 2. On the theoretical framework of research 23 2.1 On language typology and areal linguistics 23 2.1.1 On the history of language typology 24 2.1.2 On the modern language typology ' 27 2.2 Methodological principles 33 2.2.1 On statistical methods in linguistics 34 2.2.2 The variables 41 2.2.2.1 On the phonological systems of languages 41 2.2.2.2 Techniques in word-formation 43 2.2.2.3 Lexical categories 44 2.2.2.4 Categories in nominal inflection 45 2.2.2.5 Inflection of verbs 47 2.2.2.5.1 Verbal categories 48 2.2.2.5.2 Non-finite verb forms 50 2.2.2.6 Syntactic and morphosyntactic organization 52 2.2.2.6.1 The order in and between the main syntactic constituents 53 2.2.2.6.2 Agreement 54 2.2.2.6.3 Coordination and subordination 55 2.2.2.6.4 Copula 56 2.2.2.6.5 Relative clauses 56 2.2.2.7 Semantics and pragmatics 57 2.2.2.7.1 Negation 58 2.2.2.7.2 Definiteness 59 2.2.2.7.3 Thematic structure of sentences 59 3. On the typology of languages spoken in Europe and North and 61 Central Asia 3.1 The Indo-European languages 61 3.1.1 Indo-Iranian languages 63 3.1.1.1New Indo-Aryan languages 63 3.1.1.1.1 Romany 63 3.1.2 Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1 South-West Iranian languages 65 3.1.2.1.1 Tajiki 65 3.1.2.2 North-West Iranian languages 68 3.1.2.2.1 Kurdish 68 3.1.2.2.2 Northern Talysh 70 3.1.2.3 South-East Iranian languages 72 3.1.2.3.1 Pashto 72 3.1.2.4 North-East Iranian languages 74 3.1.2.4.1 -

THE LANGUAGE OFTHE SALINAN INDIANS Nominalizing Suffixes

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 1-154 January 10, 1918 THE LANGUAGE OF THE SALINAN INDIANS BY J. ALDEN MASON CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION..--.--.......------------........-----...--..--.......------........------4 PART I. P'HONOLOGY ---------7 Phonetic system ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Vowels ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Quality ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------8 Nasalization ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------8 Voiceless vowels.------------------......-------------.........-----------------......---8 Accent --------------------------------------------------9 Consonants ................---------.............--------------------...----------9 Semi-vowels ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------9 Nasals ---------- 10 Laterals -------------------------------------------------------------10 Spirants ---------------------------------------....-------------------------------------------10 Stops .--------......... --------------------------- 11 Affricatives .......................-.................-........-......... 12 Tableof phonetic system ---------------------------.-----------------13 Phonetic processes ---------------------------.-----.--............13 Vocalic assimilation ------------------..-.........------------------13 -

The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Phonology – the study of how the sounds of speech are represented in our minds – is one of the core areas of linguistic theory, and is central to the study of human language. This state-of-the-art handbook brings together the world’s leading experts in phonology to present the most comprehensive and detailed overview of the field to date. Focusing on the most recent research and the most influential theories, the authors discuss each of the central issues in phonological theory, explore a variety of empirical phenomena, and show how phonology interacts with other aspects of language such as syntax, morph- ology, phonetics, and language acquisition. Providing a one-stop guide to every aspect of this important field, The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology will serve as an invaluable source of readings for advanced undergraduate and graduate students, an informative overview for linguists, and a useful starting point for anyone beginning phonological research. PAUL DE LACY is Assistant Professor in the Department of Linguistics, Rutgers University. His publications include Markedness: Reduction and Preservation in Phonology (Cambridge University Press, 2006). The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Edited by Paul de Lacy CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521848794 © Cambridge University Press 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

URALIC MIGRATIONS: the LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE Václav

URALIC MIGRATIONS: THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE Václav Blažek For the classification of Fenno-Ugric/Uralic languages the following scenarios have been proposed: (1) Mari, Mordvin and Fenno-Saamic as coordinate sub-branches (Setälä 1890) Saamic Fenno- -Saamic Balto-Fennic Fenno- -Volgaic Mordvin Fenno- Mari -Permic Udmurt Fenno-Ugric Permic Komi Hungarian Ugric Mansi. Xanty (2) Mordvin and Mari in a Volgaic group (Collinder 1960, 11; Hajdú 1985, 173; OFUJ 1974, 39) Saamic North, East, South Saami Baltic Finnic Finnish, Ingrian, Karelian, Olonets, Ludic, Fenno-Volgaic end of the 1st mill. BC Vepsian, Votic, Estonian, Livonian 1st mill BC Mordvin Fenno- -Permic Volgaic Mari mid 2nd mill. BC Udmurt Finno-Ugric Permic end of the 8th cent. AD Komi 3rd mill. BC Hungarian Uralic Ugric 4th mill. BC mid 2st mill. BC Mansi, Xanty North Nenets, Enets, Nganasan Samoyedic end of the 1st mill. BC South Selkup; Kamasin (3) A model of a series of sequential separations by Viitso (1996, 261-66): Mordvin and Mari represent different separations from the mainstream, formed by Ugric. Fenno-Saamic Finno- Mordvin -Ugric Mari Uralic Permic Ugric (‘Core’) Samoyedic (4) The first application of a so-called ‘recalibrated’ glottochronology to Uralic languages was realized by the team of S. Starostin in 2004. -3500 -3000 -2500 -2000 -1500 -1000 -500 0 +500 +1000 +1500 +2000 Selkup Mator Samojedic -720 -210 Kamasin -550 Nganasan -340 Enets +130 Nenets Uralic Khanty -3430 Ugric Ob- +130 Mansi -1340 -Ugric Hungarian Komi Fenno-Ugric Permic +570 Udmurt -2180 Volgaic -1370 Mari -1880 Mordva -1730 Balto-Fennic Veps +220 Estonian +670 Finnish -1300 Saamic Note: G. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

B. the Program in Uralic and Altaic Studies Originated During the Academic Year

B. The Program in Uralic and Altaic Studies originated during the academic year 1960-1961, when it was known as a Comittee on Uralic and Altaic Studies. In the academic year 1961-1962 ta Jt it was transformed into a Program which then dealt, mainly with Uralic Studies - Finnish and Hungarian language and area studies. As it expanded a more complete range of courses in Uralic and Altaic Language and Area Studies were offered, and to-day the Program is probably the most comprehensive of its kind in the United States, and enjoys a world-wide reputation. Uralic and Altaic Studies is a relatively unconventional field of study concerned with an area that plays an increasing role in world affairs and embarces a great part of the Eurasian Continent. It compriaes a field of study which has hitherto been neglected in the United States. This Program now provides the much needed research facilities for graduate and doctoral students which enables them to become specialized in this field, and meets the growing need for specialists and academicians in this area. The Program offers a degree of Mafter of Arts with specialization in either Uralic or Altaic Studies. An Independent doctoral Program in Uralic and Altaic will be established during the course of the coming year. In the meantime, candidates for the Ph.D. degree present their specialization in Uralic or Altaic Studies to the curricular unit appropriate to the student' a major interest, such as linguistics, history, Asian Studies, folklore, etc. Apart from these above mentioned degrees, the Program also offers a Certificate in Hungarian Studies which is designed to stimulate interest and specialization among students who would already have accumulated some of the requirements towards unkhux another degree. -

Chapter 10. Today's Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008

Chapter 10. Today’s Ohlone/ Costanoans, 1928-2008 In 1928 three main Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived, those of Mission San Jose, Mission San Juan Bautista, and Mission Carmel. They had neither land nor federal treaty-based recognition. The 1930s, 1940s and 1950s were decades when descrimination against them and all California Indians continued to prevail. Nevertheless, the Ohlone/Costanoan communities survived and have renewed themselves. The 1960s and 1970s stand as transitional decades, when Ohlone/ Costanoans began to influence public policy in local areas. By the 1980s Ohlone/Costanoans were founding political groups and moving forward to preserve and renew their cultural heritage. By 1995 Albert Galvan, Mission San Jose descendent, could enunciate a strong positive vision of the future: I see my people, like the Phoenix, rising from the ashes—to take our rightful place in today’s society—back from extinction (Albert Galvan, personal communication to Bev Ortiz, 1995). Galvan’s statement stands in contrast to the 1850 vision of Pedro Alcantara, San Francisco native and ex-Mission Dolores descendant who was quoted as saying, “I am all that is left of my people. I am alone” (cited in Chapter 8). In this chapter we weave together personal themes, cultural themes, and political themes from the points of view of Ohlone/Costanoans and from the public record to elucidate the movement from survival to renewal that marks recent Ohlone/Costanoan history. RESPONSE TO DISCRIMINATION, 1900S-1950S Ohlone/Costanoans responded to the discrimination that existed during the first half of the twentieth century in several ways—(a) by ignoring it, (b) by keeping a low profile, (c) by passing as members of other ethnic groups, and/or (d) by creating familial and community support networks. -

The Finnish Korean Connection: an Initial Analysis

The Finnish Korean Connection: An Initial Analysis J ulian Hadland It has traditionally been accepted in circles of comparative linguistics that Finnish is related to Hungarian, and that Korean is related to Mongolian, Tungus, Turkish and other Turkic languages. N.A. Baskakov, in his research into Altaic languages categorised Finnish as belonging to the Uralic family of languages, and Korean as a member of the Altaic family. Yet there is evidence to suggest that Finnish is closer to Korean than to Hungarian, and that likewise Korean is closer to Finnish than to Turkic languages . In his analytic work, "The Altaic Family of Languages", there is strong evidence to suggest that Mongolian, Turkic and Manchurian are closely related, yet in his illustrative examples he is only able to cite SIX cases where Korean bears any resemblance to these languages, and several of these examples are not well-supported. It was only in 1927 that Korean was incorporated into the Altaic family of languages (E.D. Polivanov) . Moreover, as Baskakov points out, "the Japanese-Korean branch appeared, according to (linguistic) scien tists, as a result of mixing altaic dialects with the neighbouring non-altaic languages". For this reason many researchers exclude Korean and Japanese from the Altaic family. However, the question is, what linguistic group did those "non-altaic" languages belong to? If one is familiar with the migrations of tribes, and even nations in the first five centuries AD, one will know that the Finnish (and Ugric) tribes entered the areas of Eastern Europe across the Siberian plane and the Volga. -

Table 5-4. the North American Tribes Coded for Cannibalism by Volhard

Table 5-4. The North American tribes coded for cannibalism by Volhard and Sanday compared with all North American tribes, grouped by language and region See final page for sources and notes. Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. Family Group or Dialect Culture No. Language 1. Tribes with reports of cannibalism in Volhard, by region and language Language groups found mainly in the North and West Western Nadene Athapascan Northern Athapascan 798 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Chipewayan Northern ND7 Tschipewayan 799 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Slave Northern ND14 128 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Yellowknife Northern ND14 Subarctic Canada Northwest Salishan Coast Salish Bella Coola Bella Coola British NE6 132 Bilchula, Bilqula 795 Coast Columbia Northwest Penutian Tsimshian Tsimshian Tsimshian British NE15 Tsimschian 793 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Helltsuk Helltsuk British NE5 Heiltsuk 794 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Kwakiutl Kwakiutl British NE10 Kwakiutl* 792, 96, 97 Coast Columbia California Penutian Maidun Maidun Nisenan California NS15 Nishinam* 809, 810 California Yukian Yuklan Yuklan Wappo California NS24 Wappo 808 Language groups found mainly in the Plains Plains Sioux Dakota West Central Plains Sioux Dakota Assiniboin Assiniboin Prairie NF4 Dakota 805 Plains Sioux Dakota Gros Ventre Gros Ventre West Central NQ13 140 Plains Sioux Dakota Miniconju Miniconju West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Santee Santee West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Teton Teton West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Yankton Yankton West Central NQ11 Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No.