Sustained by First Nations: European Newcomers' Use of Indigenous Plant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIVE PLANT FIELD GUIDE Revised March 2012

NATIVE PLANT FIELD GUIDE Revised March 2012 Hansen's Northwest Native Plant Database www.nwplants.com Foreword Once upon a time, there was a very kind older gentleman who loved native plants. He lived in the Pacific northwest, so plants from this area were his focus. As a young lad, his grandfather showed him flowers and bushes and trees, the sweet taste of huckleberries and strawberries, the smell of Giant Sequoias, Incense Cedars, Junipers, pines and fir trees. He saw hummingbirds poking Honeysuckles and Columbines. He wandered the woods and discovered trillium. When he grew up, he still loved native plants--they were his passion. He built a garden of natives and then built a nursery so he could grow lots of plants and teach gardeners about them. He knew that alien plants and hybrids did not usually live peacefully with natives. In fact, most of them are fierce enemies, not well behaved, indeed, they crowd out and overtake natives. He wanted to share his information so he built a website. It had a front page, a page of plants on sale, and a page on how to plant natives. But he wanted more, lots more. So he asked for help. I volunteered and he began describing what he wanted his website to do, what it should look like, what it should say. He shared with me his dream of making his website so full of information, so inspiring, so educational that it would be the most important source of native plant lore on the internet, serving the entire world. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Rubus Arcticus Ssp. Acaulis Is Also Appreciated

Rubus arcticus L. ssp. acaulis (Michaux) Focke (dwarf raspberry): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project October 18, 2006 Juanita A. R. Ladyman, Ph.D. JnJ Associates LLC 6760 S. Kit Carson Cir E. Centennial, CO 80122 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Ladyman, J.A.R. (2006, October 18). Rubus arcticus L. ssp. acaulis (Michaux) Focke (dwarf raspberry): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/rubusarcticussspacaulis.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The time spent and help given by all the people and institutions mentioned in the reference section are gratefully acknowledged. I would also like to thank the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, in particular Bonnie Heidel, and the Colorado Natural Heritage Program, in particular David Anderson, for their generosity in making their records available. The data provided by Lynn Black of the DAO Herbarium and National Vascular Plant Identification Service in Ontario, Marta Donovan and Jenifer Penny of the British Columbia Conservation Data Center, Jane Bowles of University of Western Ontario Herbarium, Dr. Kadri Karp of the Aianduse Instituut in Tartu, Greg Karow of the Bighorn National Forest, Cathy Seibert of the University of Montana Herbarium, Dr. Anita Cholewa of the University of Minnesota Herbarium, Dr. Debra Trock of the Michigan State University Herbarium, John Rintoul of the Alberta Natural Heritage Information Centre, and Prof. Ron Hartman and Joy Handley of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium at Laramie, were all very valuable in producing this assessment. -

Natural Resource Inventory Smith-Sargent

NATURAL RESOURCE INVENTORY of the SMITH-SARGENT ROAD PROPERTY Holderness, NH FINAL REPORT [Smith-Sargent Property Upper Marsh as seen from south boundary] Compiled by: Dr. Rick Van de Poll Ecosystem Management Consultants 30 N. Sandwich Rd. Center Sandwich, NH 03227 603-284-6851 [email protected] Submitted to: Holderness Conservation Commission June 30, 2016 i SUMMARY Between October 2015 and June 2016 a comprehensive natural resources inventory (NRI) was completed by Ecosystem Management Consultants (EMC) of Sandwich, NH on the 8.5-acre town conservation land at the corner of Sargent Road and Smith Road in Holderness, NH. Managed by the Holderness Conservation Commission (HCC), this parcel was obtained largely for the complex wetland system that occupies more than 65% of the parcel. The purpose of the NRI was to inform the town about the qualities of the natural resources on the lot, as well as to determine whether or not the site would be suitable for limited environmental education for the general public. Three site visits were conducted at the Sargent-Smith Road Property for the purpose of gathering NRI data. A fourth visit was also made on November 15, 2015 for the purpose of educating the HCC and other town officials about the extent and functional value of the wetlands on the parcel. The first field visit in October provided an initial review of the location of the parcel, the boundary of the wetland, and the plant and animal resources present. A second site visit in January was held for the purpose of tracking mammals during good snow cover. -

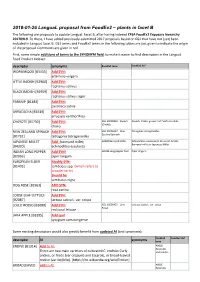

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Differential Colonization by Ecto-, Arbuscular and Ericoid Mycorrhizal Fungi in Forested Wetland Plants. by Amanda Marie Griffin

Differential colonization by ecto-, arbuscular and ericoid mycorrhizal fungi in forested wetland plants. By Amanda Marie Griffin A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Applied Science. August, 2019, Halifax, Nova Scotia © Amanda Marie Griffin, 2019 _____________________________ Approved: Gavin Kernaghan Supervisor _____________________ Approved: Dr. Jeremy Lundholm Supervisory Committee Member _____________________ Approved: Dr. Kevin Keys Supervisory Committee Member ______________________ Approved: Dr. Pedro Antunes External Examiner Date: August 26th, 2019 Differential colonization by ecto-, arbuscular and ericoid mycorrhizal fungi in forested wetland plants. by Amanda Marie Griffin Abstract The roots of most land plants are colonized by mycorrhizal fungi under normal soil conditions, yet the influence of soil moisture on different types of mycorrhizal symbioses is poorly understood. In wet soils, colonization of woody plants by ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi tends to be poor, and colonization of herbaceous plants by arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) is highly variable. However, little information is available on the influence of soil moisture on the colonization of ericaceous roots by ericoid mycorrhizal (ErM) fungi. Colonization was assessed microscopically in the ECM plant Pinus strobus, two AM plants (Cornus canadensis and Lysimachia borealis) and two ErM plants (Kalmia angustifolia and Gaultheria hispidula) along two upland to wetland gradients in Southwestern Nova Scotia. For the ErM plants, fungal ITS sequencing was used to assess community structure. The data indicate that ErM colonization increases with soil moisture in forested wetlands and is associated with distinctive fungal communities. August 26th, 2019 2 For Heidi, my constant companion. -

Native Plant List CITY of OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O

Native Plant List CITY OF OREGON CITY 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. Slope Thicket Grass Rocky Wood TREES AND ARBORESCENT SHRUBS Abies grandis Grand Fir X X X X Acer circinatumAS Vine Maple X X X Acer macrophyllum Big-Leaf Maple X X Alnus rubra Red Alder X X X Alnus sinuata Sitka Alder X Arbutus menziesii Madrone X Cornus nuttallii Western Flowering XX Dogwood Cornus sericia ssp. sericea Crataegus douglasii var. Black Hawthorn (wetland XX douglasii form) Crataegus suksdorfii Black Hawthorn (upland XXX XX form) Fraxinus latifolia Oregon Ash X X Holodiscus discolor Oceanspray Malus fuscaAS Western Crabapple X X X Pinus ponderosa Ponderosa Pine X X Populus balsamifera ssp. Black Cottonwood X X Trichocarpa Populus tremuloides Quaking Aspen X X Prunus emarginata Bitter Cherry X X X Prunus virginianaAS Common Chokecherry X X X Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir X X Pyrus (see Malus) Quercus garryana Garry Oak X X X Quercus garryana Oregon White Oak Rhamnus purshiana Cascara X X X Salix fluviatilisAS Columbia River Willow X X Salix geyeriana Geyer Willow X Salix hookerianaAS Piper's Willow X X Salix lucida ssp. lasiandra Pacific Willow X X Salix rigida var. macrogemma Rigid Willow X X Salix scouleriana Scouler Willow X X X Salix sessilifoliaAS Soft-Leafed Willow X X Salix sitchensisAS Sitka Willow X X Salix spp.* Willows Sambucus spp.* Elderberries Spiraea douglasii Douglas's Spiraea Taxus brevifolia Pacific Yew X X X Thuja plicata Western Red Cedar X X X X Tsuga heterophylla Western Hemlock X X X Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Type Wetland Riparian Forest Oak F. -

Trees, Shrubs and Vines of Toronto Is Not a Field Guide in the Typical Sense

WINNER OALA AWARD FOR SERVICE TO THE ENVIRONMENT TREES, SHRUBS & VINES OF TORONTO A GUIDE TO THEIR REMARKABLE WORLD City of Toronto Biodiversity Series Imagine a Toronto with flourishing natural habitats and an urban environment made safe for a great diversity of wildlife. Envision a city whose residents treasure their daily encounters with the remarkable and inspiring world of nature, and the variety of plants and animals who share this world. Take pride in a Toronto that aspires to be a world leader in the development of urban initiatives that will be critical to the preservation of our flora and fauna. PO Cover photo: “Impact,” sugar maple on Taylor Creek Trail by Yasmeen (Sew Ming) Tian photo: Jenny Bull Ohio buckeye, Aesculus glabra: in full flower on Toronto Island (above); the progression of Ohio buckeye flowers (counterclockwise on next page) from bud, to bud burst, to flower clusters elongating as leaves unfurl, to an open flower cluster City of Toronto © 2015 City of Toronto © 2016 ISBN 978-1-895739-77-0 “Animals rule space, Trees rule time.” – Francis Hallé 11 “Indeed, in its need for variety and acceptance of randomness, a flourishing TABLE OF CONTENTS natural ecosystem is more like a city than like a plantation. Perhaps it will be the city that reawakens our understanding and appreciation of nature, in all its teeming, unpredictable complexity.” – Jane Jacobs Welcome from Margaret Atwood and Graeme Gibson ............ 2 For the Love of Trees................................. 3 The Story of the Great Tree of Peace ...................... 4 What is a Tree?..................................... 6 Classifying Trees .................................... 9 Looking at Trees: Conifers ........................... -

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report

U.S. Geological Survey-National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park, Maine Project Report Revised Edition – October 2003 Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the U. S. Department of the Interior, U. S. Geological Survey. USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park U.S. Geological Survey-National Park Service Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park, Maine Sara Lubinski and Kevin Hop U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center and Susan Gawler Maine Natural Areas Program This report produced by U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center 2630 Fanta Reed Road La Crosse, Wisconsin 54603 and Maine Natural Areas Program Department of Conservation 159 Hospital Street 93 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0093 In conjunction with Mike Story (NPS Vegetation Mapping Coordinator) NPS, Natural Resources Information Division, Inventory and Monitoring Program Karl Brown (USGS Vegetation Mapping Coordinator) USGS, Center for Biological Informatics and Revised Edition - October 2003 USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Acadia National Park Contacts U.S. Department of Interior United States Geological Survey - Biological Resources Division Website: http://www.usgs.gov U.S. Geological Survey Center for Biological Informatics P.O. Box 25046 Building 810, Room 8000, MS-302 Denver Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225-0046 Website: http://biology.usgs.gov/cbi Karl Brown USGS Program Coordinator - USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Phone: (303) 202-4240 E-mail: [email protected] Susan Stitt USGS Remote Sensing and Geospatial Technologies Specialist USGS-NPS Vegetation Mapping Program Phone: (303) 202-4234 E-mail: [email protected] Kevin Hop Principal Investigator U.S. -

Download Printable PDF Bareroot Availability

Sevenoaks Native Nursery Bareroot Availability Sep 17, 2021 ORDERING DETAILS: Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Larix occidentalis Sold – SS = Seed Source * western larch Out – Lower prices for orders of 1000+ per species Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Cercis occidentalis Sold * – BOLD numbers indicate actual quantities western redbud Out – $5.00 charge to split bundles Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Lithocarpus densiflorus ssp. densiflorus Sold – For orders less then a full bundle, price is X * tan oak Out 3 Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Cornus nuttallii Sold * – Quantity under 100 per species, price is X 2 Pacific dogwood Out – Prices based on $200 minimum order. Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Lonicera hispidula Orders under $200 price is X 2 Sold * hairy honeysuckle Out Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Cornus sericea ssp. occidentalis Sold * creek dogwood Out Trees and Shrubs Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Lonicera involucrata SS: Linn County, OR twinberry 1/0 seedlings Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle 1900 6"/12" * 1+ 100 Sold Abies grandis * grand fir Cornus sericea ssp. sericea Out Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle redtwig dogwood SS: Lincoln County, OR Sold Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle C-1 rooted winter cuttings * Out 1/0 seedlings 100 6"/12" * 1+ 50 Acer circinatum 950 12"/18" * 1+ 50 Mahonia aquifolium vine maple 2000 6"/12" * 1+ 100 tall Oregon grape Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Cornus sericea ssp. sericea 'Baileyi' Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Sold Sold * Bailey's red twig * Out Out Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Acer glabrum c-1 rooted summer cuttings Mahonia nervosa rocky mountain maple 900 3"/6" * 1+ 50 lance-leaf Oregon grape Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Qty Size Price Stems #/Bundle Cornus sericea ssp. -

Summer 2013 Volume 24 Issue 2

Quarterly Newsletter Summer 2013 Volume 24 Issue 2 Articles Inside: A Sticky Situation: Salvia glutinosa in A Sticky Situation 1 Southeastern New York Plant Conservationist 2 by Nava Tabak Solanum dulcamara 3 Notes 6 In the young forests of southeastern plant was Salvia glutinosa. Annual Meeting Recap 7 Common Mosses Review 9 New York, invasive plants are Salvia glutinosa is a perennial herb A New Botanical Duo 10 ubiquitous and plentiful, and it is easy native to Europe and western Asia, Bark Review 11 to be lulled into the sense that we where it grows in wooded Field Trip Report 12 know all our invasive plants. After all, mountainous areas. The plant grows with garlic mustard, Japanese 50–100 cm tall, has opposite, toothed barberry, Asiatic bittersweet, tree-of- leaves with hastate bases, yellow heaven, and many others, what more corollas with brown markings, and could possibly compete here? And sticky glandular hairs on the leaves, with relatively high population stem, and calices (Tutin et al. 1972). densities, what are the chances of a As with many other species in the truly invasive species going genus, S. glutinosa is used in undetected? Imagine my surprise then, gardening, and is known to when in the fall of 2009 I encountered horticulturalists as Jupiter’s sage or a plant I did not recognize growing sticky sage. abundantly in the forest understory on With its identity revealed, I began lands near the Appalachian Trail in the to search more broadly for records of town of Dover (southeastern Dutchess this species’ introduction and County).