Production Design in the Film and Television Space: an Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8550/list-of-animated-films-and-matched-comparisons-posted-as-supplied-by-author-8550.webp)

List of Animated Films and Matched Comparisons [Posted As Supplied by Author]

Appendix : List of animated films and matched comparisons [posted as supplied by author] Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date Snow White and the G 1937 Saratoga ‘Passed’ Stella Dallas G Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio G 1940 The Great Dictator G The Grapes of Wrath unrated Bambi G 1942 Mrs. Miniver G Yankee Doodle Dandy G Cinderella G 1950 Sunset Blvd. unrated All About Eve PG Peter Pan G 1953 The Robe unrated From Here to Eternity PG Lady and the Tramp G 1955 Mister Roberts unrated Rebel Without a Cause PG-13 Sleeping Beauty G 1959 Imitation of Life unrated Suddenly Last Summer unrated 101 Dalmatians G 1961 West Side Story unrated King of Kings PG-13 The Jungle Book G 1967 The Graduate G Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner unrated The Little Mermaid G 1989 Driving Miss Daisy PG Parenthood PG-13 Beauty and the Beast G 1991 Fried Green Tomatoes PG-13 Sleeping with the Enemy R Aladdin G 1992 The Bodyguard R A Few Good Men R The Lion King G 1994 Forrest Gump PG-13 Pulp Fiction R Pocahontas G 1995 While You Were PG Bridges of Madison County PG-13 Sleeping The Hunchback of Notre G 1996 Jerry Maguire R A Time to Kill R Dame Hercules G 1997 Titanic PG-13 As Good as it Gets PG-13 Animated Film Rating Release Match 1 Rating Match 2 Rating Date A Bug’s Life G 1998 Patch Adams PG-13 The Truman Show PG Mulan G 1998 You’ve Got Mail PG Shakespeare in Love R The Prince of Egypt PG 1998 Stepmom PG-13 City of Angels PG-13 Tarzan G 1999 The Sixth Sense PG-13 The Green Mile R Dinosaur PG 2000 What Lies Beneath PG-13 Erin Brockovich R Monsters, -

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 12 February 2017 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards Only

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 12 February 2017 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Years refer to year of presentation. Leading Actor Casey Affleck 1 nomination 2017: Leading Actor (Manchester by the Sea) Andrew Garfield 2 nominations 2017: Leading Actor (Hacksaw Ridge) 2011: Supporting Actor (The Social Network) Also Rising Star nomination in 2011, one nomination (1 win) at Television Awards in 2008 Ryan Gosling 1 nomination 2017: Leading Actor (La La Land) Jake Gyllenhaall 3 nominations/1 win 2017: Leading Actor (Nocturnal Animals) 2015: Leading Actor (Nightcrawler) 2006: Supporting Actor (Brokeback Mountain) Viggo Mortensen 2 nominations 2017: Leading Actor (Captain Fantastic) 2008: Leading Actor (Eastern Promises) Leading Actress Amy Adams 6 nominations 2017: Leading Actress (Arrival) 2015: Leading Actress (Big Eyes) 2014: Leading Actress (American Hustle) 2013: Supporting Actress (The Master) 2011: Supporting Actress (The Fighter) 2009: Supporting Actress (Doubt) Emily Blunt 2 nominations 2017: Leading Actress (Girl on the Train) 2007: Supporting Actress (The Devil Wears Prada) Also Rising Star nomination in 2007 and BAFTA Los Angeles Britannia Honouree in 2009 Natalie Portman 3 nominations/1 win 2017: Leading Actress (Jackie) 2011: Leading Actress (Black Swan) 2005: Supporting Actress (Closer) Meryl Streep 15 nominations / 2 wins 2017: Leading Actress (Florence Foster Jenkins) 2012: Leading Actress (The Iron Lady) 2010: Leading Actress (Julie -

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015

EE British Academy Film Awards Sunday 8 February 2015 Previous Nominations and Wins in EE British Academy Film Awards only. Includes this year’s nominations. Wins in bold. Leading Actor Benedict Cumberbatch 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Imitation Game Eddie Redmayne 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: The Theory of Everything Orange Wednesdays Rising Star Award Nominee in 2012 Jake Gyllenhaal 2 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 2006: Brokeback Mountain Leading Actor in 2015: Nightcrawler Michael Keaton 1 nomination Leading Actor in 2015: Birdman Ralph Fiennes 6 nominations / 1 win Supporting Actor in 1994: Schindler’s List Leading Actor in 1997: The English Patient Leading Actor in 2000: The End of The Affair Leading Actor in 2006: The Constant Gardener Outstanding Debut by a British Writer, Director or Producer in 2012: Coriolanus (as Director) Leading Actor in 2015: The Grand Budapest Hotel Leading Actress Amy Adams 5 nominations Supporting Actress in 2009: Doubt Supporting Actress in 2011: The Fighter Supporting Actress in 2013: The Master Leading Actress in 2014: American Hustle Leading Actress in 2015: Big Eyes Felicity Jones 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: The Theory of Everything Julianne Moore 4 nominations Leading Actress in 2000: The End of the Affair Supporting Actress in 2003: The Hours Leading Actress in 2011: The Kids are All Right Leading Actress in 2015: Still Alice Reese Witherspoon 2 nominations / 1 win Leading Actress in 2006: Walk the Line Leading Actress in 2015: Wild Rosamund Pike 1 nomination Leading Actress in 2015: Gone Girl Supporting Actor Edward Norton 2 nominations Supporting Actor in 1997: Primal Fear Supporting Actor in 2015: Birdman Ethan Hawke 1 nomination Supporting Actor in 2015: Boyhood J. -

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: an Empirical Analysis of Music in Film

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: An Empirical Analysis of Music in Film Jon Gillick David Bamman School of Information School of Information University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Guha et al., 2015; Kociskˇ y` et al., 2017), natural language understanding (Frermann et al., 2017), Soundtracks play an important role in carry- ing the story of a film. In this work, we col- summarization (Gorinski and Lapata, 2015) and lect a corpus of movies and television shows image captioning (Zhu et al., 2015; Rohrbach matched with subtitles and soundtracks and et al., 2015, 2017; Tapaswi et al., 2015), the analyze the relationship between story, song, modalities examined are almost exclusively lim- and audience reception. We look at the con- ited to text and image. In this work, we present tent of a film through the lens of its latent top- a new perspective on multimodal storytelling by ics and at the content of a song through de- focusing on a so-far neglected aspect of narrative: scriptors of its musical attributes. In two ex- the role of music. periments, we find first that individual topics are strongly associated with musical attributes, We focus specifically on the ways in which 1 and second, that musical attributes of sound- soundtracks contribute to films, presenting a first tracks are predictive of film ratings, even after look from a computational modeling perspective controlling for topic and genre. into soundtracks as storytelling devices. By devel- oping models that connect films with musical pa- 1 Introduction rameters of soundtracks, we can gain insight into The medium of film is often taken to be a canon- musical choices both past and future. -

College Choices for the Visual and Performing Arts 2011-2012

A Complete Guide to College Choices for the Performing and Visual Arts Ed Schoenberg Bellarmine College Preparatory (San Jose, CA) Laura Young UCLA (Los Angeles, CA) Preconference Session Wednesday, June 1 MYTHS AND REALITIES “what can you do with an arts major?” Art School Myths • Lack rigor and/or structure • Do not prepare for career opportunities • No academic challenge • Should be pursued as a hobby, not a profession • Graduates are unemployable outside the arts • Must be famous to be successful • Creates starving artists Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School in the News Visual/Performing Arts majors are the… “Worst-Paid College Majors” – Time “Least Valuable College Majors” – Forbes “Worst College Majors for your Career” – Kiplinger “College Degrees with the Worst Return on Investment” – Salary.com Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School Reality Projected More than 25 28 million in 2013 million in 2020 More than 25 million people are working in arts-related industry. By 2020, this is projected to be more that 28 million – a 15% increase. (U.S. Department of Labor) Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School Reality Due to the importance of creativity in the innovation economy, more people are working in arts than ever before. Copyright: This presentation -

The Work of the Critic

CHAPTER 1 The Work of the Critic Oh, gentle lady, do not put me to’t. For I am nothing if not critical. —Iago to Desdemona (Shakespeare, Othello, Act 2, Scene I) INTRODUCTION What is the advantage of knowing how to perform television criticism if you are not going to be a professional television critic? The advantage to you as a television viewer is that you will not only be able to make informed judgment about the television programs you watch, but also you will better understand your reaction and the reactions of others who share the experience of watching. Critical acuity enables you to move from casual enjoyment of a television program to a fuller and richer understanding. A viewer who does not possess critical viewing skills may enjoy watching a television program and experience various responses to it, such as laughter, relief, fright, shock, tension, or relaxation. These are fun- damental sensations that people may get from watching television, and, for the most part, viewers who are not critics remain at this level. Critical awareness, however, enables you to move to a higher level that illuminates production practices and enhances your under- standing of culture, human nature, and interpretation. Students studying television production with ambitions to write, direct, edit, produce, and/or become camera operators will find knowledge of television criticism necessary and useful as well. Television criticism is about the evaluation of content, its context, organiza- tion, story and characterization, style, genre, and audience desire. Knowledge of these concepts is the foundation of successful production. THE ENDS OF CRITICISM Just as critics of books evaluate works of fiction and nonfiction by holding them to estab- lished standards, television critics utilize methodology and theory to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and evaluate television programs. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

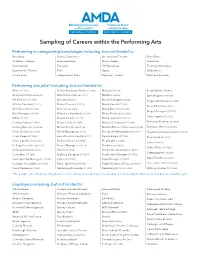

Sampling of Careers Within the Performing Arts

Sampling of Careers within the Performing Arts Performing in categories/places/stages including, but not limited to: Broadway Dance Companies International Theatre Short Films Children’s Theatre Documentaries Music Videos Television Commercials Festivals Off-Broadway Touring Companies Community Theatre Film Opera Web Series Cruise Ships Independent Films Regional Theatre West End London Performing arts jobs* including, but not limited to: Actor (27-2011) Dance Academy Owner (27-2032) Mascot (27-2090) Script Writer (27-3043) Announcer/Host (27-2010) Dance Instructor (25-1121) Model (27-2090) Set Designer (27-1027) Art Director (27-1011) Dancer (27-2031) Music Arranger (27-2041) Singer Songwriter (27-2042) Artistic Director (27-1011) Dialect Coach (25-1121) Music Coach (27-2041) Sound Editor (27-4010) Arts Educator (25-1121) Director (27-2012) Music Director (27-2041) Stage Manager (27-2010) Arts Manager (11-9190) Director’s Assistant (27-2090) Music Producer (27-2012) Talent Agent (27-2012) Ballet (27-2031) Drama Coach (25-1121) Music Teacher (25-1121) Casting Agent (27-2012) Drama Critic (27-3040) Musical Composer (27-2041) Technical Director (27-4010) Casting Director (27-2012) Drama Teacher (25-1121) Musical Theatre Musician (27-2042) Technical Writer (27-3042) Choir Director (27-2040) Event Manager (27-3030) Non-profit Administrator (43-9199) Theatre Company Owner (27-2032) Choir Singer (27-2042) Executive Assistant (43-6011) Opera Singer (27-2042) Tour Guide (39-7011) Choreographer (27-2032) Fashion Model (27-2090) Playwright (27-3043) -

David Silberberg San Francisco Bay Area Location Sound Mixer, Analogue Audio Restorer, FCP Editor, and Film-Maker

1 David Silberberg San Francisco Bay Area Location Sound Mixer, Analogue Audio Restorer, FCP Editor, and Film-maker P.O. Box 725 El Cerrito, CA 94530 (510) 847-5954 •Recording sound tracks for film and television professionally since 1989, from hand-held rough and ready documentaries to complex multicam, multitrack productions. Over 20 years experience on all kinds of documentaries, narratives, network and cable television, indie and corporate productions. Final Cut Pro Editor and award winning film-maker (for Wild Wheels and Oh My God! Itʼs Harrod Blank! ) • Recording Equipment Package Boom Mics: 3 Schoeps mics with hypercardiod capsules, Senneheiser MK-70 long shotgun mic, Schoeps bidirectional MS stereo recording, Assorted booms and windscreens Wireless Mics: 2 Lectrosonics 411 systems, 4 Lectrosonics 195D uhf diversity systems Sanken COS-11 Lavs & Sonotrim Lavs Also handheld transmitters for use with handheld mics. Mixers: Cooper CS104 mixer 4 channel: audio quality is better than excellent. Mid-Side stereo capable, as well as prefader outs—for 4 channel discreet recordings Wendt X4 MIXER : 4 channel field mixer. A standard of the broadcast industry Recorders: Sound Devices 788t HD recorder- a powerful 8 track portable recorder with SMPTE time code and CL8 controller for doing camera mixes. Edirol R-09 handheld, HHB Portadat with Time Code, Nagra 4.2, 1/4ʼʼ mono recorder, Multi-Track Recording: Using Boom Recorder software, Motu interfaces, a fast MacBook Core 2 Duo laptop, and a G-tech hard drive Iʼm now capable of recording 16 channels at 48K, 24bit—with 1 track reserved for time code. The system is clocked to the 788 t ʻs SMPTE time code output, which also records 8 more tracks and I can record a 2 channel mix on dat tape as a back-up. -

Art/Production Design Department Application Requirements

Art/Production Design Department Thank you for your interest in the Art Department of I.A.T.S.E. Local 212. Please take a few moments to read the following information, which outlines department specific requirements necessary when applying to the Art Department. The different positions within the Art/Production Department include: o Production Designer o Art Director (Head of Department) o Assistant Art Director o Draftsperson/Set Designer o Graphic Artist/Illustrator o Art Department Coordinator and o Trainee Application Requirements For Permittee Status In addition to completing the “Permit Information Package” you must meet the following requirement(s): o A valid Alberta driver’s license, o Have a strong working knowledge of drafting & ability to read drawings, o Have three years professional Design training or work experience, o Strong research abilities, o Freehand drawing ability and o Computer skills in Accounting and/or CADD and or Graphic Computer programs. APPLICANTS ARE STRONGLY RECOMMENDED TO HAVE EXPERIENCE IN ONE OR MORE OF THE FOLLOWING AREAS: o Art Departments in Film, Theatre, and Video Production o Design and Design related fields: o Video/Film and Television Art Direction & Staging o Theatrical Stage Design & Technical Direction o Architectural Design & Technology o Interior Design o Industrial Design o Graphic Design o Other film departments with proven technical skills beneficial to the needs of the Art Department. Your training and experience will help the Head of the Department (HOD) determine which position you are best suited for. Be sure to clearly indicate how you satisfy the above requirements. For example, on your resume provide detailed information about any previous training/experience (list supervisor names, responsibilities etc.) Additionally, please provide copies of any relevant licenses, tickets and/or certificates etc. -

Edmond Santa Fe Library Media Center

Edmond Santa Fe Library Media Center Staff: Angela Coffman, Librarian [email protected] Jessica Taylor, Librarian [email protected] Trish Romack, Librarian Assistant [email protected] (Please feel free to e-mail librarians with any research questions or requests for book additions to the library collection.) Library Hours 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m. Monday – Friday Student must have a pass to come to the library during class time and lunch. You may obtain a pass from an administrator or teacher at any time during the school day. Print Resources: 18,000 + books 5 ebook servers 10 + periodicals Automated Library Catalog Online Electronic Databases • American History (from the explorers to issues of today’s headlines) • EBSCO (full-text magazine, newspaper & reference book articles) • Gale In Context: Biography (over 500,000 biographies) • Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints (covering today’s prominent social issues) • Gale In Context: High school • Gale In Context: US History • Gale Literature Resource Center • Oklahoma Career Guide (database of national colleges and career information, includes several aptitude/interest inventories) • World Book Online • World History: The Modern Era (from the Renaissance to today) Each of the online electronic databases described above can be accessed at school or at home. To log on at school or at home use the Santa Fe Media Center’s web page: https://santafe.edmondschools.net/ Select Menu, Media Center, Library Catalog 1 SEARCH HELPS FOR THE LIBRARY CATALOG AND ONLINE SEARCHING LIBRARY CATALOG: Log on to the computer and open Santa Fe school website. Click on the menu, Media Center, then library catalog. -

Resume of Kim Bailey “ Feature Projects ”

Local #800 Local #44 Resume of Kim Bailey “ Feature Projects ” ADOD, LLC. 2008-Present, ADOD, LLC. (Artistic Development on Demand) (Los Angeles) C.E.O. Current entrepreneurial venture outside the scope of the entertainment industry. Business model focuses on conceptual business development, development of the brand image along with image consulting, architectural interior design and themed entertainment environments , in-house graphics, development & design of advertisement campaign relating to corporate message and trade show exhibits, product placement, web design, marketing strategies, tools & sales materials, consulting for personnel management of staff, vendors and direction of sales force. Damaged Goods 2012, Serious Damage Productions, LLC. Director: Annie Biggs (Los Angeles - PILOT) Production Designer Hired by: (Executive Producer) Annie Biggs Interfaced with: (All aspects of production) Responsible for complete design and look for all aspects of production. Pranked 2011, Untitled, LLC. Director: Adam Rifkin (Los Angeles) Supervising Art Director Hired by: (Producer) Bernie Gewissler Interfaced with: (Production, Director & Executive Producer) Responsible for complete design and look for all aspects of production. The Wrath of Shatner 2010, Free Enterprise 2, LLC. Director: Robert Burnett (Los Angeles) Supervising Art Director to Production Designer Hired by: (Producer) Jeffrey Cohglan Interfaced with: (Production & Director) Responsible for complete design and look for all aspects of production, took over for Production designer