Reality Television Production As Dirty Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One and Only

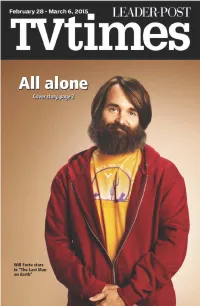

Cover Story One and only Fox tackles the loneliest number in ‘The Last Man on Earth’ By Cassie Dresch people after a virus takes out him get into a lot of really silly TV Media all of Earth’s population. His shenanigans. family is gone, his coworkers “It’s all just kind of stupid ello? Hi? Anybody out are gone, the president is gone. stuff that I go around and do,” Hthere? Of course there is, Everyone. Gone. he said in an interview with otherwise life would be very, So what does he do? He “Entertainment Weekly.” very, very lonely. Fox is taking a travels the United States doing “That’s been one of the most stab at the ultimate life of lone- things he never would have fun parts of the job. About once liness in the new half-hour been able to do otherwise — a week I get to do something comedy “The Last Man on sing the national anthem at that seems like it’d be amaz- Earth,” premiering Sunday, Dodger Stadium, smear gooey ingly fun to do: shoot a flame March 1. peanut butter all over a price- thrower at a bunch of wigs, The premise around “Last less piece of art ... then walk have a steamroller steamroll Man” is a simple one, albeit a away with it, break things. The over a case of beer. Just dumb little strange. An average, un- show, according to creator and stuff like that, which pretty assuming man is on the hunt star Will Forte (“Saturday Night much is all it takes to make me for any signs of other living Live,” “Nebraska,” 2013), sees happy.” Registration $25.00 online: www.skseniorsmechanism.ca or phone 306-359-9956 2 Cover Story Flame throwers and steam- ally proud of what has come rollers? Again, it’s a strange out of it so far.” concept, but Fox is really be- Of course, you have to won- Index hind the show. -

Gdowth Should Detudn...Some

INFORMATION AND ANALYSIS FOR THE THOROUGHBRED INVESTOR JUNE 2010 Yearling Sales Preview By Eric Mitchell 2. YEARLING AUCTION REVIEW GROWTH SHOULD RETURN...SOME BY SALE, '05-'07 hat will happen in the Thoroughbred yearling and the overall quality of the horses should improve 4. LEADING Wmarket is particularly hard to predict this year. as sellers become more selective about the yearlings CONSIGNORS OF Many influences of equal importance, both positive and they offer. The ROR should also improve slightly com- YEARLINGS '05-'07 negative, could shape the market, but which of these pared with 2009. The select 2-year-olds sales experi- influences will predominate is the big question. enced an increase in ROR to 70%, up from 30% in 2008. 5. LEADING BUYERS In 2009 the rate of return on pinhooked yearlings hit The average juvenile price improved to $160,732 from OF YEARLINGS a rock-bottom low of -42.2%. It didn’t help sellers that $147,528. Clearly, there is still an appetite for acquiring '05-'07 these horses had been bred on the highest average stud Thoroughbreds, so an increase in the average yearling fee ($31,462) seen in the last 10 years, and the average price between 5% and 10% is not unreasonable, though 6. RACING STATS yearling price also fell 31% as part of the fallout from the such an increase would still produce losing RORs for the FOR SUMMER global financial crisis. pinhook yearling market. The average pinhook yearling SIRES PROGENY Sellers don't get any relief on the cost side this year price would have to grow at least 18% to $57,884 for sell- because North American stud fees were still relatively ers to break even collectively. -

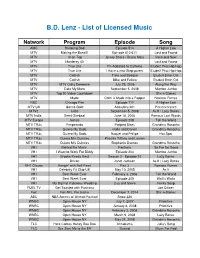

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

Usability and User Experience in the True Crime

Running head: SERIALIZED KILLING 1 SERIALIZED KILLING: USABILITY AND USER EXPERIENCE IN THE TRUE CRIME GENRE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY CATHERINE M. TRAYLOR DR. KEVIN T. MOLONEY – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2019 SERIALIZED KILLING 2 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Kevin Moloney, who consistently allowed this paper to be my own work while steering me in the right direction, providing a fresh perspective, and patiently responding to a multitude of emails. I would also like to acknowledge my committee members Dr. Jennifer Palilonis and Dr. Kristen McCauliff. I am grateful to them for their valuable comments on my work and support throughout the process. My deep appreciation goes to my survey respondents and focus group participants for their candid responses and willingness to give of their time. Special thanks to my parents, who always made education a priority in our home and a possibility in my life. Finally, thank you to Zach McFarland for enduring countless nights of thesis edits and reworks. Your patience and encouragement did not go unnoticed. SERIALIZED KILLING 3 Abstract THESIS: SerialiZed Killing: Usability and User Experience in the True Crime Genre STUDENT: Catherine M. Traylor DEGREE: Master of Arts COLLEGE: College of Communication, Information and Media DATE: July 2019 PAGES: 31 True crime, a genre that has piqued the interest of individuals for decades, has taken on a new form in the age of digital media. Through television shows, podcasts, books, and community- driven online forums, investigations of the coldest of cases are met with newfound enthusiasm and determination from professional storytellers and armchair detectives alike. -

The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes

Media Industries 5.2 (2018) The Fan/Creator Alliance: Social Media, Audience Mandates, and the Rebalancing of Power in Studio–Showrunner Disputes Annemarie Navar-Gill1 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN amngill [AT] umich.edu Abstract Because companies, not writer-producers, are the legally protected “authors” of television shows, when production disputes between series creators and studio/ network suits arise, executives have every right to separate creators from their intellectual property creations. However, legally disempowered series creators can leverage an audience mandate to gain the upper hand in production disputes. Examining two case studies where an audience mandate was involved in overturning a corporate production decision—Rob Thomas’s seven-year quest to make a Veronica Mars movie and Dan Harmon’s firing from and subsequent rehiring to his position as the showrunner of Community—this article explores how the social media ecosystem around television rebalances power in disputes between creators and the corporate entities that produce and distribute their work. Keywords: Audiences, Authorship, Management, Production, Social Media, Television Scripted television shows have always had writers. For the most part, however, until the post-network era, those writers were not “authors.” As Catherine Fisk and Miranda Banks have shown in their respective historical accounts of the WGA (Writers Guild of America), television writers have a long history of negotiating the terms of what “authorship” meant in the context of their work, but for most of the medium’s history, the cultural validation afforded to an “author” eluded them.2 This began to change, however, in the 1990s, when the term “showrunner” began to appear in television trade press.3 “Showrunner” is an unofficial title referring to the executive producer and head writer of a television series, who acts in effect as the show’s CEO, overseeing the program’s story development and having final authority in essentially all production decisions. -

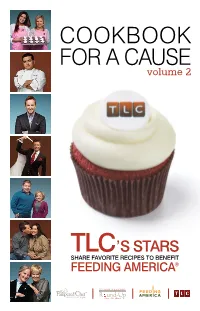

COOKBOOK for a CAUSE Volume 2

COOKBOOK FOR A CAUSE volume 2 TLC’S STARS SHARE FAVORITE RECIPES TO BENEFIT FEEDING AMERICA® FIGHTING HUNGER IN AMERICA ONE COOKBOOK at A TIME. The Pampered Chef® Cookbook for a Cause, Volume 2 benefits Feeding America®, the nation’s largest domestic hunger-relief organization. This year, the popular television network TLC® joined our mission to help fight hunger. TLC® stars from Cake Boss, Say Yes to the Dress, DC Cupcakes, The Little Couple, 19 Kids and Counting, What Not To Wear, and more, generously contributed their favorite recipes, in their own words. For each cookbook sold, we’ll donate $1 to Feeding America® to help provide eight meals to those in need.* We hope you’ll enjoy these recipes from the TLC® stars and the helpful tips and techniques from the experts in The Pampered Chef® Test Kitchens. As you gather around the table with family and friends, you can feel good that you’re helping another family in need to do the same. The Pampered Chef® The Pampered Chef® is the largest direct seller of everything you need to cook and entertain at home. At in-home Cooking Shows, guests see and try products, prepare and sample recipes, and learn quick and easy food preparation techniques and tips on how to entertain with style and ease — transforming the everyday into the extraordinary. TLC® is all about real-life reality, transporting the viewers into the lives of real-life extraordinary people with character. TLC® programs are entertaining, unfiltered and always reveal something worthwhile. TLC® is curious about people and finding the extraordinary in the everyday. -

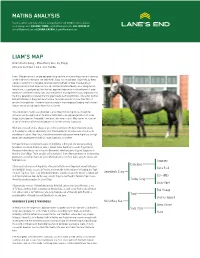

Mating Analysis Liam's

MATING ANALYSIS You may submit your mare online at lanesend.com or call 859-873-7300 to discuss your matings with CHANCE TIMM, [email protected], JILL MCCULLY, [email protected] or LEVANA CAPRIA, [email protected]. LIAM’S MAP Unbridled’s Song - Miss Macy Sue, by Trippi 2011 Gray/roan | 16.1 1/2 Hands Liam’s Map possesses a unique pedigree that gives him an outstanding chance of carrying on the male line of the great sire Unbridled’s Song. His second dam, Yada Yada, by Great Above, is inbred 2x3 to the great racemare and broodmare Ta Wee. That pattern of having a closely inbred ancestor close up, whether it be broodmare sire or along the tail- female line, is a pedigree pattern that has appeared repeatedly in the pedigrees of great racehorses and line-founding sires since the dawn of thoroughbred history, beginning with the horse generally considered the first great racehorse Flying Childers, whose full brother Bartlett’s Childers is the grandsire of Eclipse, tail-male ancestor of more than 95% of modern Thoroughbreds. The most recent example is the unexpected leading sire Distorted Humor, whose second dam is inbred 3x3 to Turn-to. Since Unbridled’s Song’s sire Unbridled is also inbred 4x4 to Aspidistra, through her immortal son Dr. Fager (sire of the dam of Unbridled’s sire Fappiano) and his half-sister Magic, by Buckpasser, Unbridled’s third dam, that means Liam’s Map carries four crosses of one of the most influential broodmares of the 20th century, Aspidistra. With any new stallion it is always a good idea to reinforce the most important strains of his pedigree, and it is abundantly clear that Aspidistra’s influence was critical to the excellence of Liam’s Map. -

Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F. Miller University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Miller, A. F.(2015). Redneckaissance: Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3217 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REDNECKAISSANCE: HONEY BOO BOO, TUMBLR, AND THE STEREOTYPE OF POOR WHITE TRASH by Ashley F. Miller Bachelor of Arts Emory University, 2006 Master of Fine Arts Florida State University, 2008 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mass Communications College of Information and Communications University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: August Grant, Major Professor Carol Pardun, Committee Member Leigh Moscowitz, Committee Member Lynn Weber, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Ashley F. Miller, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements Although her name is not among the committee members, this study owes a great deal to the extensive help of Kathy Forde. It could not have been done without her. Thanks go to my mother and fiancé for helping me survive the process, and special thanks go to L. Nicol Cabe for ensuring my inescapable relationship with the Internet and pop culture. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

B4 the MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 6:30 7:30 8:30 9:30

B4 B4 THE MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 03/9 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10AM 10:30 11AM 11:30 WBKO ^ 5:30 AM Kentucky (N) Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å WBKO at Midday (N) % Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å The 700 Club (N) Å WHAG News at 12:00PM (N) _ _ Paid Program Storm Stories Å Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Local 7 News Lifestyles Family Feud Å Family Feud Å Animal Adv Å Swift Justice Å Judge Mathis Å 3 ( 5:00 The Daily Buzz Å Better (N) Å Cash Cab Å Cash Cab Å The Cosby Show Å The Cosby Show Å Law & Order: Criminal Intent Å C ) 5:00 QVC This Morning Perricone MD Cosmeceuticals Kitchen Innovations LizClaiborne New York Fashion. Q Check Style Edition . * 14 News Sunrise (N) Å Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å Today (N) Å Today (N) Å :15 Midday With Mike (N) Å 9 + 5:00 Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Å Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å FreeCruise Paid Program ) , Arthur (EI) Å Martha Speaks Å Curious George Å Cat in the Hat Å Super Why! Å Dinosaur Train Å Sesame Street (EI) Å Sid the Science Å WordWorld (EI) Å Super Why! Å Barney & Friends Å L ` Morning News Å Morning News Å CBS This Morning Ewan McGregor; Grant Hill. (N) Å The Doctors (N) Å The Price Is Right (N) Å The Young and the Restless (N) Å & 2 BBC World News Å Kentucky Health Å Body Electric Å TV 411 Å GED Connection Å GED Connection Å Paint This-Jerry Å Quilt in a Day Å Knitting Daily Å Beads, Baubles Å Charlie Rose Å WGN / Paid Program Paid Program Bewitched Å Dream of Jeannie Å Matlock “The Ghost” Å Matlock “The Class” Å In the Heat of the Night “Discovery” Å In the Heat of the Night Å INSP 1 Int’nl Fellowship Life Today Å Creflo Dollar Å Feed the Children Victory Today Life Today Å Joseph Prince Å Joyce Meyer Å Humanitarian Int’nl Fellowship The Waltons “The Idol” TBN 5 Spring Praise-A-Thon Spring Praise-A-Thon HGTV 7 Destination De Marriage/Const. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

Class of 1964 Th 50 Reunion

Class of 1964 th 50 Reunion BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY 50th Reunion Special Thanks On behalf of the Offi ce of Development and Alumni Relations, we would like to thank the members of the Class of 1964 Reunion Committee Joel M. Abrams, Co-chair Ellen Lasher Kaplan, Co-chair Danny Lehrman, Co-chair Eve Eisenmann Brooks, Yearbook Coordinator Charlotte Glazer Baer Peter A. Berkowsky Joan Paller Bines Barbara Hayes Buell Je rey W. Cohen Howard G. Foster Michael D. Freed Frederic A. Gordon Renana Robkin Kadden Arnold B. Kanter Alan E. Katz Michael R. Lefkow Linda Goldman Lerner Marya Randall Levenson Michael Stephen Lewis Michael A. Oberman Stuart A. Paris David M. Phillips Arnold L. Reisman Leslie J. Rivkind Joe Weber Jacqueline Keller Winokur Shelly Wolf Class of 1964 Timeline Class of 1964 Timeline 1961 US News • John F. Kennedy inaugurated as President of the United World News States • East Germany • Peace Corps offi cially erects the Berlin established on March Wall between East 1st and West Berlin • First US astronaut, to halt fl ood of Navy Cmdr. Alan B. refugees Shepard, Jr., rockets Movies • Beginning of 116.5 miles up in 302- • The Parent Trap Checkpoint Charlie mile trip • 101 Dalmatians standoff between • “Freedom Riders” • Breakfast at Tiffany’s US and Soviet test the United States • West Side Story Books tanks Supreme Court Economy • Joseph Heller – • The World Wide decision Boynton v. • Average income per TV Shows Catch 22 Died this Year Fund for Nature Virginia by riding year: $5,315 • Wagon Train • Henry Miller - • Ty Cobb (WWF) started racially integrated • Unemployment: • Bonanza Tropic of Cancer • Carl Jung • 40 Dead Sea interstate buses into the 5.5% • Andy Griffi th • Lewis Mumford • Chico Marx Scrolls are found South.