Honey Boo Boo, Tumblr, and the Stereotype of Poor White Trash Ashley F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

" Ht Tr H" : Trtp Nd N Nd Tnf P Rhtn Th

ht "ht Trh": trtp nd n ndtn f Pr ht n th .. nnl Ntz, tth r Minnesota Review, Number 47, Fall 1996 (New Series), pp. 57-72 (Article) Pblhd b D nvrt Pr For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mnr/summary/v047/47.newitz.html Access provided by Middlebury College (11 Dec 2015 16:54 GMT) Annalee Newitz and Matthew Wray What is "White Trash"? Stereotypes and Economic Conditions of Poor Whites in the U.S. "White trash" is, in many ways, the white Other. When we think about race in the U.S., oftentimes we find ourselves constrained by cat- egories we've inherited from a kind of essentialist multiculturalism, or what we call "vulgar multiculturalism."^ Vulgar multiculturalism holds that racial and ethic groups are "authentically" and essentially differ- ent from each other, and that racism is a one-way street: it proceeds out of whiteness to subjugate non-whiteness, so that all racists are white and all victims of racism are non-white. Critical multiculturalism, as it has been articulated by theorists such as those in the Chicago Cultural Studies Group, is one example of a multiculturalism which tries to com- plicate and trouble the dogmatic ways vulgar multiculturalism has un- derstood race, gender, and class identities. "White trash" identity is one we believe a critical multiculturalism should address in order to further its project of re-examining the relationships between identity and social power. Unlike the "whiteness" of vulgar multiculturalism, the whiteness of "white trash" signals something other than privilege and social power. -

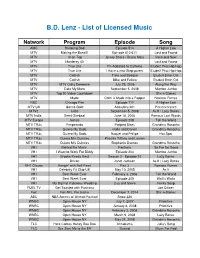

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

CONNECT PREP Onair & Social Media Ready Features, Kickers and Interviews

CONNECT PREP OnAir & Social Media ready features, kickers and interviews. FOR FRIDAY, June 19th, 2020 CORONAVIRUS LIFE Pods Are The Latest Gym Craze AUDIO: Pete Sapsin SOCIAL MEDIA: Photo LENGTH: 00:00:18 LEAD: No, this isn't a science fiction fantasy. Pod gyms are really happening. And they could be coming to a city near you. With states across the U-S still seeing a rise in coronavirus cases, there has been a demand to go back to working out at the local gym. Well, Pete Sapsin of California's Inspire Fitness figured out a way to follow social distancing guidelines while working out. He told Inside Edition he and his wife thought of the pod idea. The total cost to make one of the pods? A whopping 400 dollars. OUTCUE: came the pods Grandparents Love VR Vacations AUDIO: Ian Sherr, editor at large, CNET LENGTH: 00:00:31 LEAD: Lonely seniors in Coronavirus quarantine lockdowns are really enjoying Virtual Reality vacations. CNET's Ian Sherr reports: OUTCUE: around you PROTESTS Juneteenth Celebrations Planned Across The U.S. AUDIO: Ludacris LENGTH: 00:00:07 LEAD: Strike up the music, Juneteenth celebrations are happening across the U-S. The unofficial American holiday, which is celebrated annually on June 19th, commemorates the ending of slavery. With the recent Black Lives Matter protests over the death of George Floyd, there has been renewed interest in celebrating the importance of freedom in our history. Rapper and actor Ludacris told Entertainment Tonight that this year may be the biggest Juneteenth yet. OUTCUE: many different ways Eerie Video Of Rayshard Brooks Released AUDIO: Rayshard Brooks SOCIAL MEDIA: Video LENGTH: 00:00:16 LEAD: An eerie video has surfaced of police shooting victim Rayshard Brooks. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

The N-Word : Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings Anne V

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2009 The N-word : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings Anne V. Benfield Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Benfield, Anne V., "The -wN ord : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings" (2009). Honors Theses. 1433. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1433 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The N-Word: Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings By Anne V. Benfield * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Sociology UNION COLLEGE June, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Literature Review Etymology 7 Early Uses 8 Fluidity in the Twentieth Century 11 The Commercialization of Nigger 12 The Millennium 15 Race as a Determinant 17 Gender Binary 19 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 23 Generational Difference 25 Chapter Two: Methodology Sociological Theories 29 W.E.B DuBois’ “Double-Consciousness” 34 Qualitative Research Instrument: Focus Groups 38 Chapter Three: Results and Discussion Demographics 42 Generational Difference 43 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 47 Gender Binary 51 Race as a Determinant 55 The Ambiguity of Nigger vs. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 66–75 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2391 Article “Trailer Trash” Stigma and Belonging in Florida Mobile Home Parks Margarethe Kusenbach Department of Sociology, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 1 August 2019 | Accepted: 4 October 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract In the United States, residents of mobile homes and mobile home communities are faced with cultural stigmatization regarding their places of living. While common, the “trailer trash” stigma, an example of both housing and neighbor- hood/territorial stigma, has been understudied in contemporary research. Through a range of discursive strategies, many subgroups within this larger population manage to successfully distance themselves from the stigma and thereby render it inconsequential (Kusenbach, 2009). But what about those residents—typically white, poor, and occasionally lacking in stability—who do not have the necessary resources to accomplish this? This article examines three typical responses by low-income mobile home residents—here called resisting, downplaying, and perpetuating—leading to different outcomes regarding residents’ sense of community belonging. The article is based on the analysis of over 150 qualitative interviews with mobile home park residents conducted in West Central Florida between 2005 and 2010. Keywords belonging; Florida; housing; identity; mobile homes; stigmatization; territorial stigma Issue This article is part of the issue “New Research on Housing and Territorial Stigma” edited by Margarethe Kusenbach (University of South Florida, USA) and Peer Smets (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the Netherlands). © 2020 by the author; licensee Cogitatio (Lisbon, Portugal). This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International License (CC BY). -

The Pioneer Chinese of Utah

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1976 The Pioneer Chinese of Utah Don C. Conley Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Conley, Don C., "The Pioneer Chinese of Utah" (1976). Theses and Dissertations. 4616. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4616 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE PIONEER CHINESE OF UTAH A Thesis Presented to the Department of Asian Studies Brigham Young University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Don C. Conley April 1976 This thesis, by Don C. Conley, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Asian Studies of Brigham Young University as satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Russell N. Hdriuchi, Department Chairman Typed by Sharon Bird ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author gratefully acknowledges the encourage ment, suggestions, and criticisms of Dr. Paul V. Hyer and Dr. Eugene E. Campbell. A special thanks is extended to the staffs of the American West Center at the University of Utah and the Utah Historical Society. Most of all, the writer thanks Angela, Jared and Joshua, whose sacrifice for this study have been at least equal to his own. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter 1. -

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of February 10Th and February 17Th (As of 2.3.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of February 10th and February 17th (as of 2.3.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of February 10th and 17th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. TLC PRESS CONTACT: Jordyn Linsk: 240-662-2421 [email protected] TH WEEK OF FEBRUARY 10 (as of 2.3.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Special Premieres SAY YES TO THE DRESS: THE BIG DAY – Friday, February 14 UNTOLD STORIES OF THE ER: SEX EDITION – Saturday, February 15 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 10 9:00PM ET/PT CAKE BOSS – “BICEPS AND BIRTHDAYS” Buddy rolls up his sleeves and shows off his muscles when he must make a cake for a family of professional arm wrestlers. And Mauro and his kids plan a surprise romantic birthday celebration for Madeline inside the bakery. TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 11 9:00PM ET/PT MY 600-LB. LIFE – “PAULA’S STORY” Paula has had a tough life, and at over 600lbs, has built a physical wall around herself to push people away. When she suddenly loses someone she loves, Paula can no longer ignore the threat of losing her own life – especially for her children’s sake. WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12 9:00PM ET/PT HOARDING: BURIED ALIVE – “A VCR FOR EVERY DAY OF THE WEEK” John and Joe are a father and son duo who both hoard. Their home—which has no functional bedroom or usable kitchen—is packed to the ceiling with items the pair has relentlessly accumulated over the past decade. -

Maternal Representation in Reality Television: Critiquing New Momism in Tlc’S Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and Jon & Kate Plus 8

MATERNAL REPRESENTATION IN REALITY TELEVISION: CRITIQUING NEW MOMISM IN TLC’S HERE COMES HONEY BOO BOO AND JON & KATE PLUS 8 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Isabel Silva, B.A. Washington, DC March 24, 2014 Copyright 2014 by Isabel Silva All Rights Reserved ii MATERNAL REPRESENTATION IN REALITY TELEVISION: CRITIQUING NEW MOMISM IN TLC’S HERE COMES HONEY BOO BOO AND JON & KATE PLUS 8 Isabel Silva, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Pamela A. Fox , Ph.D . ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways that TLC’s reality programs, specifically Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and Jon and Kate Plus Eight, serve as hegemonic systems for the perpetuation of what Susan Douglas and Meredith Michaels call “new momism.” As these authors demonstrate in The Mommy Myth, the media have served as a powerful hegemonic force in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for the construction of this dominating ideology of proper motherhood which undermines the social victories of feminism. Expanding upon Douglas’ and Michaels’ analysis of national constructions of motherhood, I explore the role of reality television, a relatively new cultural medium, within the historical tradition of hegemonic institutions. My research examines representations of motherhood specifically within reality programs which document a family’s day- to-day life, differing from other types of reality shows because they take place within the private sphere of the home. These programs market performances of motherhood that invite viewers, specifically those who are mothers themselves, to construct their own identities in opposition to “transgressive” mothers and in awe of “ideal” mothers, thereby reaffirming the oppressive and unreasonable expectations of twenty-first century motherhood. -

Celebrity Endorsers Vs. Social Influencers Vrinda Soma a Thesis

Celebrity Endorsers vs. Social Influencers Vrinda Soma A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Business (MBus). 2019 Faculty of Business, Economics and Law 1 Abstract The purpose of this research is to measure how effective social influencers and celebrity endorsers are in persuading individuals to like, purchase and/or share information about a brand or specific product. Previous literature has discussed how different source characteristics and endorsers influence individuals. However, rapid change in information and communication channel evolution means that the research on endorsements conducted before social media channels arose is in need of updates and extensions to examine how current forms of communication drive brand conversations. Source characteristics impact how a social influencer or celebrity endorser is effective when communicating to an audience. In the endorsement setting, the most important attributes are trustworthiness, expertise, attractiveness, authenticity and credibility (Erdogan, 1999). As the literature shows, these attributes are the most likely to contribute to attitude change and eventual behaviour change (Erdogan, 1999; Kapitan & Silvera, 2016). These attributes have been individually studied for celebrity endorsers (i.e., Erdogan, 1999), however, the rise of online social influencers makes it important to re-evaluate and compare and contrast social influencers and celebrity endorsers so that brands, endorsers and researchers have a better understanding of what viewers are looking for. Two areas of interest drive the quantitative research undertaken in this thesis: (1) an evaluation between attitudes generated by social influencers and celebrity endorsers and (2) the willingness to purchase an endorsed product or brand depending on endorser type.