How to Write a TV Pilot, Pt. 1: Concept & Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

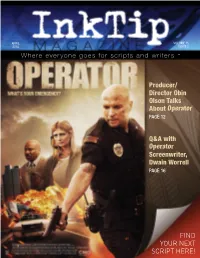

Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12

APRIL VOLUME 15 2015 ISSUE 2 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers ™ Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12 Q&A with Operator Screenwriter, Dwain Worrell PAGE 16 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! Where everyone goes for writers and scripts™ IT’S FAST AND EASY TO FIND THE SCRIPT OR WRITER YOU NEED. WWW.INKTIP.COM A FREE SERVICE FOR ENTERTAINMENT PROFESSIONALS. Peruse this magazine, find the scripts/books you like, and go to www.InkTip.com to search by title or author for access to synopses, resumes and scripts! l For more information, go to: www.InkTip.com. l To register for access, go to: www.InkTip.com and click Joining InkTip for Entertainment Pros l Subscribe to our free newsletter at http://www.inktip.com/ep_newsletters.php Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they can place their scripts on our site. Table of Contents Recent Successes 3, 9, 11 Feature Scripts – Grouped by Genre 7 Industry Endorsements 3 Feature Article: Operator 12 Contest/Festival Winners 4 Q&A: Operator Screenwriter Dwain Worrell 16 Writers Represented by Agents/Managers 4 Get Your Movie on the Cover of InkTip Magazine 18 Teleplays 5 3 Welcome to InkTip! The InkTip Magazine is owned and distributed by InkTip. Recent Successes In this magazine, we provide you with an extensive selection of loglines from all genres for scripts available now on InkTip. Entertainment professionals from Hollywood and all over the Bethany Joy Lenz Options “One of These Days” world come to InkTip because it is a fast and easy way to find Bethany Joy Lenz found “One of These Days” on InkTip, great scripts and talented writers. -

How to Format Your Script

How to format your Script Many screenwriting books specify formats that may not still be in general use today, or which contain directions that may be unnecessary. The following format tips are accurate and will result in your screenplay being formatted in the correct manner. These tips apply only to a spec script. A production script contains editing and camera directions (and scene numbers) all of which are only added after a script goes into production, and should not be included in a spec script, the purpose of which is only to present the basic story. How the story is interpreted on the screen is up to the director, not the writer. LENGTH: Ideally, a screenplay for a regular feature film for theatrical release or for television should be between 100 and 120 pages. DO NOT list a cast of characters before the first page of the script. And, DO NOT number the scenes. THERE ARE ONLY THREE ELEMENTS NECESSARY IN A SPEC SCRIPT: · THE SCENE HEADING (INTERIOR OR EXTERIOR, LOCATION, TIME) · THE VISUAL EXPOSITION (Only what you would see if you were watching the screen) · THE DIALOGUE (1) The Scene Heading sets the stage for the action and dialogue to follow. It tells us where the story is taking place, and the time of day. There are only two locations where this can happen, inside (INT) or outside (EXT). The specific location and geographic placement should be included as well. The scene heading is positioned on your first indent, one-and-a-half inches in from the left hand side of the page. -

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: an Empirical Analysis of Music in Film

Telling Stories with Soundtracks: An Empirical Analysis of Music in Film Jon Gillick David Bamman School of Information School of Information University of California, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] Abstract (Guha et al., 2015; Kociskˇ y` et al., 2017), natural language understanding (Frermann et al., 2017), Soundtracks play an important role in carry- ing the story of a film. In this work, we col- summarization (Gorinski and Lapata, 2015) and lect a corpus of movies and television shows image captioning (Zhu et al., 2015; Rohrbach matched with subtitles and soundtracks and et al., 2015, 2017; Tapaswi et al., 2015), the analyze the relationship between story, song, modalities examined are almost exclusively lim- and audience reception. We look at the con- ited to text and image. In this work, we present tent of a film through the lens of its latent top- a new perspective on multimodal storytelling by ics and at the content of a song through de- focusing on a so-far neglected aspect of narrative: scriptors of its musical attributes. In two ex- the role of music. periments, we find first that individual topics are strongly associated with musical attributes, We focus specifically on the ways in which 1 and second, that musical attributes of sound- soundtracks contribute to films, presenting a first tracks are predictive of film ratings, even after look from a computational modeling perspective controlling for topic and genre. into soundtracks as storytelling devices. By devel- oping models that connect films with musical pa- 1 Introduction rameters of soundtracks, we can gain insight into The medium of film is often taken to be a canon- musical choices both past and future. -

Introduction Screenwriting Off the Page

Introduction Screenwriting off the Page The product of the dream factory is not one of the same nature as are the material objects turned out on most assembly lines. For them, uniformity is essential; for the motion picture, originality is important. The conflict between the two qualities is a major problem in Hollywood. hortense powdermaker1 A screenplay writer, screenwriter for short, or scriptwriter or scenarist is a writer who practices the craft of screenwriting, writing screenplays on which mass media such as films, television programs, comics or video games are based. Wikipedia In the documentary Dreams on Spec (2007), filmmaker Daniel J. Snyder tests studio executive Jack Warner’s famous line: “Writers are just sch- mucks with Underwoods.” Snyder seeks to explain, for example, why a writer would take the time to craft an original “spec” script without a mon- etary advance and with only the dimmest of possibilities that it will be bought by a studio or producer. Extending anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker’s 1950s framing of Hollywood in the era of Jack Warner and other classic Hollywood moguls as a “dream factory,” Dreams on Spec pro- files the creative and economic nightmares experienced by contemporary screenwriters hoping to clock in on Hollywood’s assembly line of creative uniformity. There is something to learn about the craft and profession of screenwrit- ing from all the characters in this documentary. One of the interviewees, Dennis Palumbo (My Favorite Year, 1982), addresses the downside of the struggling screenwriter’s life with a healthy dose of pragmatism: “A writ- er’s life and a writer’s struggle can be really hard on relationships, very hard for your mate to understand. -

Summer 2019 Vol.21, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2019 VOL.21, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA A Rock Star in the Writers’ Room: Bringing Jann Arden to the small screen Crafting Canadian Horror Stories — and why we’re so good at it Celebrating the 23rd annual WGC Screenwriting Awards Emily Andras How she turned PM40011669 Wynonna Earp into a fan phenomenon Congratulations to Emily Andras of SPACE’s Wynonna Earp, Sarah Dodd of CTV’s Cardinal, and all of the other 2019 WGC Screenwriting Award winners. Proud to support Canada’s creative community. CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 21 No. 3 Summer 2019 ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Publisher Maureen Parker Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Contents Director of Communications Lana Castleman Cover Editorial Advisory Board There’s #NoChill When it Comes Michael Amo to Emily Andras’s Wynonna Earp 6 Michael MacLennan How 2019’s WGC Showrunner Award winner Emily Susin Nielsen Andras and her room built a fan and social media Simon Racioppa phenomenon — and why they’re itching to get back in Rachel Langer the saddle for Wynonna’s fourth season. President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) By Li Robbins Councillors Michael Amo (Atlantic) Features Mark Ellis (Central) What Would Jann Do? 12 Marsha Greene (Central) That’s exactly the question co-creators Leah Gauthier Alex Levine (Central) and Jennica Harper asked when it came time to craft a Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) heightened (and hilarious) fictional version of Canadian Andrew Wreggitt (Western) icon Jann Arden’s life for the small screen. -

The Work of the Critic

CHAPTER 1 The Work of the Critic Oh, gentle lady, do not put me to’t. For I am nothing if not critical. —Iago to Desdemona (Shakespeare, Othello, Act 2, Scene I) INTRODUCTION What is the advantage of knowing how to perform television criticism if you are not going to be a professional television critic? The advantage to you as a television viewer is that you will not only be able to make informed judgment about the television programs you watch, but also you will better understand your reaction and the reactions of others who share the experience of watching. Critical acuity enables you to move from casual enjoyment of a television program to a fuller and richer understanding. A viewer who does not possess critical viewing skills may enjoy watching a television program and experience various responses to it, such as laughter, relief, fright, shock, tension, or relaxation. These are fun- damental sensations that people may get from watching television, and, for the most part, viewers who are not critics remain at this level. Critical awareness, however, enables you to move to a higher level that illuminates production practices and enhances your under- standing of culture, human nature, and interpretation. Students studying television production with ambitions to write, direct, edit, produce, and/or become camera operators will find knowledge of television criticism necessary and useful as well. Television criticism is about the evaluation of content, its context, organiza- tion, story and characterization, style, genre, and audience desire. Knowledge of these concepts is the foundation of successful production. THE ENDS OF CRITICISM Just as critics of books evaluate works of fiction and nonfiction by holding them to estab- lished standards, television critics utilize methodology and theory to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and evaluate television programs. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Air-To-Ground Battle for Italy

Air-to-Ground Battle for Italy MICHAEL C. MCCARTHY Brigadier General, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2004 Air University Library Cataloging Data McCarthy, Michael C. Air-to-ground battle for Italy / Michael C. McCarthy. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-128-7 1. World War, 1939–1945 — Aerial operations, American. 2. World War, 1939– 1945 — Campaigns — Italy. 3. United States — Army Air Forces — Fighter Group, 57th. I. Title. 940.544973—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112–6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix INTRODUCTION . xi Notes . xiv 1 GREAT ADVENTURE BEGINS . 1 2 THREE MUSKETEERS TIMES TWO . 11 3 AIR-TO-GROUND BATTLE FOR ITALY . 45 4 OPERATION STRANGLE . 65 INDEX . 97 Photographs follow page 28 iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Foreword The events in this story are based on the memory of the author, backed up by official personnel records. All survivors are now well into their eighties. Those involved in reconstructing the period, the emotional rollercoaster that was part of every day and each combat mission, ask for understanding and tolerance for fallible memories. Bruce Abercrombie, our dedicated photo guy, took most of the pictures. -

David Silberberg San Francisco Bay Area Location Sound Mixer, Analogue Audio Restorer, FCP Editor, and Film-Maker

1 David Silberberg San Francisco Bay Area Location Sound Mixer, Analogue Audio Restorer, FCP Editor, and Film-maker P.O. Box 725 El Cerrito, CA 94530 (510) 847-5954 •Recording sound tracks for film and television professionally since 1989, from hand-held rough and ready documentaries to complex multicam, multitrack productions. Over 20 years experience on all kinds of documentaries, narratives, network and cable television, indie and corporate productions. Final Cut Pro Editor and award winning film-maker (for Wild Wheels and Oh My God! Itʼs Harrod Blank! ) • Recording Equipment Package Boom Mics: 3 Schoeps mics with hypercardiod capsules, Senneheiser MK-70 long shotgun mic, Schoeps bidirectional MS stereo recording, Assorted booms and windscreens Wireless Mics: 2 Lectrosonics 411 systems, 4 Lectrosonics 195D uhf diversity systems Sanken COS-11 Lavs & Sonotrim Lavs Also handheld transmitters for use with handheld mics. Mixers: Cooper CS104 mixer 4 channel: audio quality is better than excellent. Mid-Side stereo capable, as well as prefader outs—for 4 channel discreet recordings Wendt X4 MIXER : 4 channel field mixer. A standard of the broadcast industry Recorders: Sound Devices 788t HD recorder- a powerful 8 track portable recorder with SMPTE time code and CL8 controller for doing camera mixes. Edirol R-09 handheld, HHB Portadat with Time Code, Nagra 4.2, 1/4ʼʼ mono recorder, Multi-Track Recording: Using Boom Recorder software, Motu interfaces, a fast MacBook Core 2 Duo laptop, and a G-tech hard drive Iʼm now capable of recording 16 channels at 48K, 24bit—with 1 track reserved for time code. The system is clocked to the 788 t ʻs SMPTE time code output, which also records 8 more tracks and I can record a 2 channel mix on dat tape as a back-up. -

Limitations on Copyright Protection for Format Ideas in Reality Television Programming

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING By Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen* * Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen are partners in the Entertainment, Media, and Technology Group in the Century City, California and Washington, D.C. offices, respectively, of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP. The authors thank Ben Aigboboh, an associate in the Century City office, for his assistance with this article. 97 For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I. INTRODUCTION Television networks constantly compete to find and produce the next big hit. The shifting economic landscape forged by increasing competition between and among ever-proliferating media platforms, however, places extreme pressure on network profit margins. Fully scripted hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies have become increasingly costly, while delivering diminishing ratings in the key demographics most valued by advertisers. It therefore is not surprising that the reality television genre has become a staple of network schedules. New reality shows are churned out each season.1 The main appeal, of course, is that they are cheap to make and addictive to watch. Networks are able to take ordinary people and create a show without having to pay “A-list” actor salaries and hire teams of writers.2 Many of the most popular programs are unscripted, meaning lower cost for higher ratings. Even where the ratings are flat, such shows are capable of generating higher profit margins through advertising directed to large groups of more readily targeted viewers. -

New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola

Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, Shelley Stamp New Histories of Hollywood Roundtable Moderated by Luci Marzola As part of this issue on “The System Beyond the Studios,” I sought not only to give scholars an opportunity to publish work that looks at specific cases reassessing the history of Hollywood, but I also wanted to look more broadly at the state of the field of American film history. As such, I assembled a roundtable of scholars who have been studying Hollywood through myriad lenses for most of their careers. I wanted to know, from their perspective, what were the current and future threads to be taken up in the study of this central topic in cinema and media studies. The roundtable discussion focuses on innovative methods, sources, and approaches that give us new insights into the study of Hollywood. Chris Cagle, Emily Carman, Mark Garrett Cooper, Kate Fortmueller, Eric Hoyt, Denise McKenna, Ross Melnick, and Shelley Stamp all participated while I moderated the conversation. It was conducted via email and Google docs in the fall of 2017. Each participant began by writing a brief response to a broad question on one topic – research, methodology, pedagogy, or the meaning of ‘Hollywood.’ These responses were then culled together and given follow up questions which were all placed in a Google drive folder. Over the course of two months, the participants added responses, provocations, and questions on each of the threads, while I added follow up questions to guide the discussion. When seen as a whole, this roundtable creates a snapshot of where the field of Hollywood history is at this moment. -

Jennifer Chovancek

JENNIFER CHOVANCEK ASSISTANT PRODUCTION COORDINATOR 1-95 Malvern Ave. Toronto On M4E 3E6 C.416-844-6780 [email protected] Assistant Production Workin’ Moms Television Series CBC Coordinator Producers: Catherine Reitman, Philip 07-11, 2016 Sternberg, Jonathan Walker PM: Anthony Pangalos PC: Michelle Kanyo Assistant Production The Stanley Dynamic II Television Sitcom YTV Coordinator Producers: Teza Lawrence, Michael 08, 2015 - 04, 2016 Souther, Ken Cuperus, Victoria Hirst PM: Maribeth Daley PC: Alison Waxman 2nd Unit Assistant Warrior TV Pilot NBC Production Producer: Marc David Alpert 03-04, 2015 Coordinator PM: Brian Campbell PC: Keitha Redmond Production The Stanley Dynamic Television Sitcom YTV Coordinator Producers: Teza Lawrence, Michael 05-12, 2014 Souther, Ken Cuperus, Victoria Hirst PM: Maribeth Daley Assistant Production The Stanley Dynamic Television Sitcom YTV Coordinator Producers: Teza Lawrence, Michael 02-05, 2014 Souther, Ken Cuperus, Victoria Hirst PM: Maribeth Daley PC: Alison Waxman Travel Coordinator The Best Laid Plans TV Mini Series CBC Producers: Brian Dennis, Phyllis Platt, 05-12, 2013 Peter Moss PM: Mary Pantelidis Assistant Production The F Word Feature Film No Trace Coordinator Producers: Jessie Shapira, Jeff Arkuss, 05-11, 2012 Camping David Gross, Hartley Gorenstein PM: Reggie Robb PC: Alison Waxman Assistant Production COPPER Television Series Cineflix/ BBC/ Coordinator Producers: Glen Salzman, Brad Van 12, 2011-03,2012 Shaw Arragon PM: Chris Danton PC: Nancy Jackson Assistant Production Sunshine Sketches