Introduction Screenwriting Off the Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moral Questions Concerning Story in Immersive Hypertext Narrative

Thoughts On Some Moral Questions Concerning Story In Immersive Hypertext Narrative Mark Bernstein1 1 Eastgate Systems, Inc, 134 Main Street, Watertown Massachusetts USA [email protected] Abstract. The moral dangers of fiction have always alarmed commentators, but immersive interaction gives rise to new qualms derived not from fiction’s indulgence of untruth nor in the sexual license of itinerant players, but that grow from immersion, from fictive immersive experiences that resist reflection. Keywords: Hypertext, Fiction, Storytelling, Narrative. 1 Twenty Years On The Holodeck Twenty years have elapsed since Janet Murray’s Hamlet On The Holodeck [1] argued that the future of new media lay in vividly immersive, encyclopedic and emotional interactive experi- ences rather than in the intertexual, allusive, lyrical and intellectual(ized) works that had epito- mized new media through the preceding decade [2]. Murray’s vision of immersive dialogic experience been enormously influential throughout new media. In these notes, I would like to call attention to a number of questions and sources of disquiet that arise in composing immersive works in which the reader intentionally and effectually acts to change the events that take place in the story1. These issues are not new but they have not been widely discussed, and drawing them together in this context may have some value. These are not hypothetical or invented questions. Most actually arose in the course of my writing a hypertext school story, Those Trojan Girls [6]. Others were familiar to me from edit- ing and publishing hypertext fictions over several decades. Reflective practice is an important source of insight, and its judicious use can prove invaluable [7]. -

GCWC WAG Creative Writing

GASTON COLLEGE Creative Writing Writing Center I. GENERAL PURPOSE/AUDIENCE Creative writing may take many forms, such as fiction, creative non-fiction, poetry, playwriting, and screenwriting. Creative writers can turn almost any situation into possible writing material. Creative writers have a lot of freedom to work with and can experiment with form in their work, but they should also be aware of common tropes and forms within their chosen style. For instance, short story writers should be aware of what represents common structures within that genre in published fiction and steer away from using the structures of TV shows or movies. Audiences may include any reader of the genre that the author chooses to use; therefore, authors should address potential audiences for their writing outside the classroom. What’s more, students should address a national audience of interested readers—not just familiar readers who will know about a particular location or situation (for example, college life). II. TYPES OF WRITING • Fiction (novels and short stories) • Creative non-fiction • Poetry • Plays • Screenplays Assignments will vary from instructor to instructor and class to class, but students in all Creative Writing classes are assigned writing exercises and will also provide peer critiques of their classmates’ work. In a university setting, instructors expect prose to be in the realistic, literary vein unless otherwise specified. III. TYPES OF EVIDENCE • Subjective: personal accounts and storytelling; invention • Objective: historical data, historical and cultural accuracy: Work set in any period of the past (or present) should reflect the facts, events, details, and culture of its time and place. -

The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic«

DOI 10.1515/jlt-2013-0006 JLT 2013; 7(1–2): 135–153 Ted Nannicelli The Ontology and Literary Status of the Screenplay:The Case of »Scriptfic« Abstract: Are screenplays – or at least some screenplays – works of literature? Until relatively recently, very few theorists had addressed this question. Thanks to recent work by scholars such as Ian W. Macdonald, Steven Maras, and Steven Price, theorizing the nature of the screenplay is back on the agenda after years of neglect (albeit with a few important exceptions) by film studies and literary studies (Macdonald 2004; Maras 2009; Price 2010). What has emerged from this work, however, is a general acceptance that the screenplay is ontologically peculiar and, as a result, a divergence of opinion about whether or not it is the kind of thing that can be literature. Specifically, recent discussion about the nature of the screenplay has tended to emphasize its putative lack of ontological autonomy from the film, its supposed inherent incompleteness, or both (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48; Price 2010, 38–42). Moreover, these sorts of claims about the screenplay’s ontology – its essential nature – are often hitched to broader arguments. According to one such argument, a screenplay’s supposed ontological tie to the production of a film is said to vitiate the possibility of it being a work of literature in its own right (Carroll 2008, 68–69; Maras 2009, 48). According to another, the screenplay’s tenuous literary status is putatively explained by the idea that it is perpetually unfinished, akin to a Barthesian »writerly text« (Price 2010, 41). -

A Wishy-Washy, Sort-Of-Feeling: Episodes in the History of the Wishy-Washy Aesthetic

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-22-2014 12:00 AM A Wishy-Washy, Sort-of-Feeling: Episodes in the History of the Wishy-Washy Aesthetic Amy Gaizauskas The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Christine Sprengler The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Art History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Amy Gaizauskas 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Gaizauskas, Amy, "A Wishy-Washy, Sort-of-Feeling: Episodes in the History of the Wishy-Washy Aesthetic" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2332. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2332 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A WISHY-WASHY, SORT-OF FEELING: EPISODES IN THE HISTORY OF THE WISHY-WASHY AESTHETIC Thesis Format: Monograph by Amy Gaizauskas Graduate Program in Art History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Amy Gaizauskas 2014 Abstract Following Sianne Ngai’s Our Aesthetic Categories (2012), this thesis studies the wishy- washy as an aesthetic category. Consisting of three art world and visual culture case studies, this thesis reveals the surprising strength that lies behind the wishy-washy’s weak veneer. -

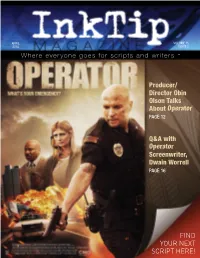

Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12

APRIL VOLUME 15 2015 ISSUE 2 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers ™ Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12 Q&A with Operator Screenwriter, Dwain Worrell PAGE 16 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! Where everyone goes for writers and scripts™ IT’S FAST AND EASY TO FIND THE SCRIPT OR WRITER YOU NEED. WWW.INKTIP.COM A FREE SERVICE FOR ENTERTAINMENT PROFESSIONALS. Peruse this magazine, find the scripts/books you like, and go to www.InkTip.com to search by title or author for access to synopses, resumes and scripts! l For more information, go to: www.InkTip.com. l To register for access, go to: www.InkTip.com and click Joining InkTip for Entertainment Pros l Subscribe to our free newsletter at http://www.inktip.com/ep_newsletters.php Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they can place their scripts on our site. Table of Contents Recent Successes 3, 9, 11 Feature Scripts – Grouped by Genre 7 Industry Endorsements 3 Feature Article: Operator 12 Contest/Festival Winners 4 Q&A: Operator Screenwriter Dwain Worrell 16 Writers Represented by Agents/Managers 4 Get Your Movie on the Cover of InkTip Magazine 18 Teleplays 5 3 Welcome to InkTip! The InkTip Magazine is owned and distributed by InkTip. Recent Successes In this magazine, we provide you with an extensive selection of loglines from all genres for scripts available now on InkTip. Entertainment professionals from Hollywood and all over the Bethany Joy Lenz Options “One of These Days” world come to InkTip because it is a fast and easy way to find Bethany Joy Lenz found “One of These Days” on InkTip, great scripts and talented writers. -

Philosophy, Theory, and Literature

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PHILOSOPHY, THEORY, AND LITERATURE 20% DISCOUNT NEW & FORTHCOMING ON ALL TITLES 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Redwood Press .............................2 Square One: First-Order Questions in the Humanities ................... 2-3 Currencies: New Thinking for Financial Times ...............3-4 Post*45 ..........................................5-7 Philosophy and Social Theory ..........................7-10 Meridian: Crossing Aesthetics ............10-12 Cultural Memory in the Present ......................... 12-14 Literature and Literary Studies .................... 14-18 This Atom Bomb in Me Ordinary Unhappiness Shakesplish The Long Public Life of a History in Financial Times Asian and Asian Lindsey A. Freeman The Therapeutic Fiction of How We Read Short Private Poem Amin Samman American Literature .................19 David Foster Wallace Shakespeare’s Language Reading and Remembering This Atom Bomb in Me traces what Critical theorists of economy tend Thomas Wyatt Digital Publishing Initiative ....19 it felt like to grow up suffused with Jon Baskin Paula Blank to understand the history of market American nuclear culture in and In recent years, the American fiction Shakespeare may have written in Peter Murphy society as a succession of distinct around the atomic city of Oak Ridge, writer David Foster Wallace has Elizabethan English, but when Thomas Wyatt didn’t publish “They stages. This vision of history rests on ORDERING Tennessee. As a secret city during been treated as a symbol, an icon, we read him, we can’t help but Flee from Me.” It was written in a a chronological conception of time Use code S19PHIL to receive a the Manhattan Project, Oak Ridge and even a film character. Ordinary understand his words, metaphors, notebook, maybe abroad, maybe whereby each present slips into the 20% discount on all books listed enriched the uranium that powered Unhappiness returns us to the reason and syntax in relation to our own. -

Why Does the Screenwriter Cross the Road…By Joe Gilford 1

WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 1 WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD? …and other screenwriting secrets. by Joe Gilford TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (included on this web page) 1. FILM IS NOT A VISUAL MEDIUM 2. SCREENPLAYS ARE NOT WRITTEN—THEY’RE BUILT 3. SO THERE’S THIS PERSON… 4. SUSTAINABLE SCREENWRITING 5. WHAT’S THE WORST THAT CAN HAPPEN?—THAT’S WHAT HAPPENS! 6. IF YOU DON’T BELIEVE THIS STORY—WHO WILL?? 7. TOOLBAG: THE TRICKS, GAGS & GADGETS OF THE TRADE 8. OK, GO WRITE YOUR SCRIPT 9. NOW WHAT? INTRODUCTION Let’s admit it: writing a good screenplay isn’t easy. Any seasoned professional, including me, can tell you that. You really want it to go well. You really want to do a good job. You want those involved — including yourself — to be very pleased. You really want it to be satisfying for all parties, in this case that means your characters and your audience. WHY DOES THE SCREENWRITER CROSS THE ROAD…BY JOE GILFORD 2 I believe great care is always taken in writing the best screenplays. The story needs to be psychically and spiritually nutritious. This isn’t a one-night stand. This is something that needs to be meaningful, maybe even last a lifetime, which is difficult even under the best circumstances. Believe it or not, in the end, it needs to make sense in some way. Even if you don’t see yourself as some kind of “artist,” you can’t avoid it. You’re going to be writing this script using your whole psyche. -

Strategic Stories: an Analysis of the Profile Genre Amy Jessee Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2009 Strategic Stories: An Analysis of the Profile Genre Amy Jessee Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jessee, Amy, "Strategic Stories: An Analysis of the Profile Genre" (2009). All Theses. 550. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/550 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STRATEGIC STORIES: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PROFILE GENRE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Professional Communication by Amy Katherine Jessee May 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Sean Williams, Committee Chair Dr. Susan Hilligoss Dr. Mihaela Vorvoreanu ABSTRACT This case study examined the form and function of student profiles published on five university websites. This emergent form of the profile stems from antecedents in journalism, biography, and art, while adapting to a new rhetorical situation: the marketization of university discourse. Through this theoretical framework, universities market their products and services to their consumer, the student, and stories of current students realize and reveal a shift in discursive practices that changes the way we view universities. A genre analysis of 15 profiles demonstrates how their visual patterns and obligatory move structure create a cohesive narrative and two characters. They strategically show features of a successful student fitting with the institutional values and sketch an outline of the institutional identity. -

How to Format Your Script

How to format your Script Many screenwriting books specify formats that may not still be in general use today, or which contain directions that may be unnecessary. The following format tips are accurate and will result in your screenplay being formatted in the correct manner. These tips apply only to a spec script. A production script contains editing and camera directions (and scene numbers) all of which are only added after a script goes into production, and should not be included in a spec script, the purpose of which is only to present the basic story. How the story is interpreted on the screen is up to the director, not the writer. LENGTH: Ideally, a screenplay for a regular feature film for theatrical release or for television should be between 100 and 120 pages. DO NOT list a cast of characters before the first page of the script. And, DO NOT number the scenes. THERE ARE ONLY THREE ELEMENTS NECESSARY IN A SPEC SCRIPT: · THE SCENE HEADING (INTERIOR OR EXTERIOR, LOCATION, TIME) · THE VISUAL EXPOSITION (Only what you would see if you were watching the screen) · THE DIALOGUE (1) The Scene Heading sets the stage for the action and dialogue to follow. It tells us where the story is taking place, and the time of day. There are only two locations where this can happen, inside (INT) or outside (EXT). The specific location and geographic placement should be included as well. The scene heading is positioned on your first indent, one-and-a-half inches in from the left hand side of the page. -

Spectacle Theater

SUN MON TUES Wed thurs fri SAT 1 2 3 4 5 SPECTACLE 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 PROTECTORS OF THE Queen of burlesque THE PINK EGG EAT MY DUST LADY OF BURLESQUE UNIVERSE Director Q&A! 7:30 10:00 10:00 10:00 FLASH FUTURE KUNG FU SPACE THUNDER KIDS HARD BASTARD 10:00 LITTLE MAD GUY 10:00 LADY OF BURLESQUE DArnA VS. THE PLANET WOMEN Midnight HERCULES UNCHAINED Midnight THE HORROR OF SPIDER ISLAND 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 blood brunch the pink egg Solar adventure dog day pizza, birra, Faso flash future kung fu lady of burlesque 5:00 7:30 keep cool 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 darna vs. the planet lost & forgotten cinema little mad guy space transformer eat my dust protectors of the space thunder kids women 7:30 universe Contemporary underground • special events Queen of burlesque 10:00 Midnight hard bastard the horror of spider island Midnight I.K.U. 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 & 10:00 5:00 fist church hard bastard pizza, birra, Faso Queen of burlesque dog day silent lovers yeast ONE NIGHT ONLY! 5:00 7:30 the pink egg 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 8Ball tv space transformer keep cool darna vs. the planet solar adventure Midnight ONE NIGHT ONLY! 7:30 women the horror of spider eat my dust island 10:00 little mad guy Midnight hercules unchained 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 3:00 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 7:30 5:00 blood brunch solar adventure MATCH CUTS PRESENTS Queen of burlesque eat my dust keep cool space transformer ONE NIGHT ONLY! 5:00 7:30 flash future kung fu 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 10:00 space thunder kids dog day I.K.U hard bastard YEAST the pink egg 7:30 10:00 space thunder kids I.K.U. -

The Speed of the VCR

Edinburgh Research Explorer The speed of the VCR Citation for published version: Davis, G 2018, 'The speed of the VCR: Ti West's slow horror', Screen, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 41-58. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjy003 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1093/screen/hjy003 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Screen Publisher Rights Statement: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Screen following peer review. The version of record Glyn Davis; The speed of the VCR: Ti West’s slow horror, Screen, Volume 59, Issue 1, 1 March 2018, Pages 41–58 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjy003. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 The speed of the VCR: Ti West’s slow horror GLYN DAVIS In Ti West’s horror film The House of the Devil (2009), Samantha (Jocelin Donahue), a college student short of cash, takes on a babysitting job. -

Satirical News Detection and Analysis Using Attention Mechanism and Linguistic Features

Satirical News Detection and Analysis using Attention Mechanism and Linguistic Features Fan Yang and Arjun Mukherjee Eduard Gragut Department of Computer Science Computer and Information Sciences University of Houston Temple University fyang11,arjun @uh.edu [email protected] { } Abstract ... “Kids these days are done with stories where things happen,” said CBC consultant and world's oldest child Satirical news is considered to be enter- psychologist Obadiah Sugarman. “We'll finally be giv- tainment, but it is potentially deceptive ing them the stiff Victorian morality that I assume is in and harmful. Despite the embedded genre vogue. Not to mention, doing a period piece is a great way to make sure white people are adequately repre- in the article, not everyone can recognize sented on television.” the satirical cues and therefore believe the ... news as true news. We observe that satiri- Table 1: A paragraph of satirical news cal cues are often reflected in certain para- graphs rather than the whole document. Existing works only consider document- gardless of the ridiculous content1. It is also con- level features to detect the satire, which cluded that fake news is similar to satirical news could be limited. We consider paragraph- via a thorough comparison among true news, fake level linguistic features to unveil the satire news, and satirical news (Horne and Adali, 2017). by incorporating neural network and atten- This paper focuses on satirical news detection to tion mechanism. We investigate the differ- ensure the trustworthiness of online news and pre- ence between paragraph-level features and vent the spreading of potential misleading infor- document-level features, and analyze them mation.