AIR TRANSPORT the Single Market Review Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE 1 PROFILES W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRLINES SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS Lufthansa 1 Lufthansa 1,739,886 Ryanair 2 Ryanair 1,604,799 Air France 3 Air France 1,329,819 easyJet Britis 4 easyJet 1,200,528 Airways 5 British Airways 1,025,222 SAS 6 SAS 703,817 airberlin KLM Royal 7 airberlin 609,008 Dutch Airlines 8 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 571,584 Iberia 9 Iberia 534,125 Other Western 10 Norwegian Air Shuttle 494,828 W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRPORTS SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 Europe R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS 1 London Heathrow Airport 1,774,606 2 Paris Charles De Gaulle Airport 1,421,231 Outlook 3 Frankfurt Airport 1,394,143 4 Amsterdam Airport Schiphol 1,052,624 5 Madrid Barajas Airport 1,016,791 HE EUROPEAN AIRLINE MARKET 6 Munich Airport 1,007,000 HAS A NUMBER OF DIVIDING LINES. 7 Rome Fiumicino Airport 812,178 There is little growth on routes within the 8 Barcelona El Prat Airport 768,004 continent, but steady growth on long-haul. MostT of the growth within Europe goes to low-cost 9 Paris Orly Field 683,097 carriers, while the major legacy groups restructure 10 London Gatwick Airport 622,909 their short/medium-haul activities. The big Western countries see little or negative traffic growth, while the East enjoys a growth spurt ... ... On the other hand, the big Western airline groups continue to lead consolidation, while many in the East struggle to survive. -

Champion Brands to My Wife, Mercy the ‘Made in Germany’ Champion Brands Nation Branding, Innovation and World Export Leadership

The ‘Made in Germany’ Champion Brands To my wife, Mercy The ‘Made in Germany’ Champion Brands Nation Branding, Innovation and World Export Leadership UGESH A. JOSEPH First published 2013 by Gower Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © Ugesh A. Joseph 2013 Ugesh A. Joseph has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. Gower Applied Business Research Our programme provides leaders, practitioners, scholars and researchers with thought provoking, cutting edge books that combine conceptual insights, interdisciplinary rigour and practical relevance in key areas of business and management. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Joseph, Ugesh A. The ‘Made in Germany’ champion brands: nation branding, innovation and world export leadership / by Ugesh A. Joseph. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-6646-8 (hardback: alk. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

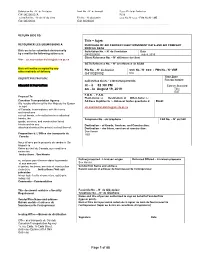

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

September 2001 Interesting Times CONTENTS He Airline Industry Is Living in Interesting Times, As the Old Tchinese Curse Has It

Aviation Strategy Issue No: 47 September 2001 Interesting times CONTENTS he airline industry is living in interesting times, as the old TChinese curse has it. Analysis There are more and more signs of weakening economies, but the official indicators are not pointing to a recession, ie an absolute down-turn in activity The OECD's mid-year Economic Outlook Industry outlook 1 highlights the slow-down in the US economy from real GDP growth of 5.0% in 2000 to 1.9% this year, though a recovery to 3.1% is Sabena, forced to face expected for 2002. The EU is just slightly down this year - GDP reality 2-3 growth of 2.6% against 3.1% in 2000 - and next year is put at 2.7%. Japan, however, continues to plod along its L-shaped recession - 1.3% in 2000, 1.2% in 2001, 0.7% in 2002. Oneworld and SkyTeam: The airlines that are suffering disproportionately are those that Justifying immunity 4-6 followed strategies of tight capacity curtailment yield enhancement and focus on business travel. The US Majors' second quarter Briefing results were unprecedently bad - an operating loss of $0.8bn against a $2.8bn profit a year ago. BA, according to a widely Embraer: new challenges for reported analysis from Merrill Lynch, will be turning to losses for Brazil’s success story 7-10 2001/02. The reason that the airline downturn is worse than that implied KLM: Still searching for by the economic number probably has a lot to do with the collapse a sustainable role 8-14 of the new technology sector. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

Prof. Paul Stephen Dempsey

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2008 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Before Alliances, there was Pan American World Airways . and Trans World Airlines. Before the mega- Alliances, there was interlining, facilitated by IATA Like dogs marking territory, airlines around the world are sniffing each other's tail fins looking for partners." Daniel Riordan “The hardest thing in working on an alliance is to coordinate the activities of people who have different instincts and a different language, and maybe worship slightly different travel gods, to get them to work together in a culture that allows them to respect each other’s habits and convictions, and yet work productively together in an environment in which you can’t specify everything in advance.” Michael E. Levine “Beware a pact with the devil.” Martin Shugrue Airline Motivations For Alliances • the desire to achieve greater economies of scale, scope, and density; • the desire to reduce costs by consolidating redundant operations; • the need to improve revenue by reducing the level of competition wherever possible as markets are liberalized; and • the desire to skirt around the nationality rules which prohibit multinational ownership and cabotage. Intercarrier Agreements · Ticketing-and-Baggage Agreements · Joint-Fare Agreements · Reciprocal Airport Agreements · Blocked Space Relationships · Computer Reservations Systems Joint Ventures · Joint Sales Offices and Telephone Centers · E-Commerce Joint Ventures · Frequent Flyer Program Alliances · Pooling Traffic & Revenue · Code-Sharing Code Sharing The term "code" refers to the identifier used in flight schedule, generally the 2-character IATA carrier designator code and flight number. Thus, XX123, flight 123 operated by the airline XX, might also be sold by airline YY as YY456 and by ZZ as ZZ9876. -

The Airline That Knows Greece Best We Are … AEGEAN

The airline that knows Greece best We are … AEGEAN Full service carrier, Greece’s ………. ………. largest airline focused on quality since 2008 services & efficiency We fly to ………. We own 61 aircraft ………. 145 destinations in 40 countries 7 times awarded Star Alliance ………. as Best Regional ………. member Airline in Europe since 2010 We are … AEGEAN Acquisition of ………. Olympic Air in ………. 6 hubs in Greece and 2013 1 in Cyprus Total coverage of all ………. Scheduled & charter, Greek destinations, ………. even in small islands short & medium haul (via Olympic Air) services in Europe & Middle East Timeline of key events, evolution of passenger traffic 2016 2015 Delivery of 7 14,0 6th time new aircraft awarded by A320ceo Skytrax 12,5 13,0 2011 2013 Intl traffic Olympic Air 11,6 2003 exceeds Acquired 12,0 First Year with domestic for Profits before Taxes 2007 the fist time Listing in Stock 11,0 Market, First 2010 10,2 2003 A320 2005 Aegean joins Low Cost Carriers Deliveries Lufthansa Star Alliance enter Greek Market 10,0 Agreement, 8,8 2001 Airbus A320 Merger with Order 9,0 Cronus, First Intl Olympic Flights 1999/2000 8,0 Air Greece 2002–2003 acquisition Olympic and Aegean sole competitors 6,6 6,5 6,2 6,1 7,0 5,9 May 1999 Domestic 5,2 6,0 Deregulation. Launch of Scheduled 4,5 Million of Passengers 5,0 Flights International 4,0 3,6 4,0 2,8 2,5 3,0 2,4 2,0 1,5 0,3 Domestic 1,0 0,0 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 20164 2016 Report destinations available aircraft 61 145 16,2mil. -

University of the Aegean Shipping, Trade and Transport Department

University of the Aegean Shipping, Trade and Transport Department Georgia Tsitsou “High-speed rail and air transport competition: The case of Athens – Thessaloniki” 16/10/2019 Research Dissertation for the Master Program “Shipping, Trade and Transport Department – ΝΑΜΕ” Author: Georgia Tsitsou Supervisor: Seraphim Kapros Chios 1 Abstract This research dissertation analyses the potential of the high speed train to compete with the airline market. The context proposed is hypothetical, given that the high speed train alternative is not yet available on the route subject to research. In order to model passenger preferences relative to the characteristics of the alternatives, experimental design techniques are applied, which allow for the design of the market that will be evaluated by current airline passengers. Based upon the information collected, modal choices are analysed, estimating a logit model with both alternatives. Demand modelling allows us to predict the substitutability level of the high speed train in comparison with the plane for the city pair Athens – Thessaloniki and in reverse, for different types of traveler. The results obtained confirm that the high speed train will have an important impact on the airline market. The simulation of different policies related to service variables stresses the fact that this impact will mainly depend on the relation gender – price, age – time, occupancy – accuracy/ reliability and reasons for travelling – accuracy/ reliability. In contrast, in the city pair Thessaloniki – Athens, there is statistically significant correlation between gender and fewer stops or better connections and reason for travelling and price. Suggestions that were provided at the final part of the dissertation concentrate on gaining a better overview of passengers’ preference for each mode of transport and needs by conducting a respective research in train platforms. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L.