Filmmaking from the Perspective of the Production Designer Jane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stanley Kubrick's 18Th Century

Stanley Kubrick’s 18th Century: Painting in Motion and Barry Lyndon as an Enlightenment Gallery Alysse Peery Abstract The only period piece by famed Stanley Kubrick, Barry Lyndon, was a 1975 box office flop, as well as the director’s magnum opus. Perhaps one of the most sumptuous and exquisite examples of cinematography to date, this picaresque film effectively recreates the Age of the Enlightenment not merely through facts or events, but in visual aesthetics. Like exploring the past in a museum exhibit, the film has a painterly quality harkening back to the old masters. The major artistic movements that reigned throughout the setting of the story dominate the manner in which Barry Lyndon tells its tale with Kubrick’s legendary eye for detail. Through visual understanding, the once obscure novel by William Makepeace Thackeray becomes a captivating window into the past in a manner similar to the paintings it emulates. In 1975, the famed and monumental director Stanley Kubrick released his one and only box-office flop. A film described as a “coffee table film”, it was his only period piece, based on an obscure novel by William Makepeace Thackeray (Patterson). Ironically, his most forgotten work is now considered his magnum opus by critics, and a complete masterwork of cinematography (BFI, “Art”). A remarkable example of the historical costume drama, it enchants the viewer in a meticulously crafted vision of the Georgian Era. Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon encapsulates the painting, aesthetics, and overall feel of the 18th century in such a manner to transform the film into a sort of gallery of period art and society. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

JUDGE ROY BEAN - Mentale Sidespring

har bragt filmens forskellige elementer ■ DET BLODRØDE BRYLLUP tage cykelturen i »Butch Cassidy and Les noces rouges. Frankrig/ltalien 1973. P-selskab: sammen i en høj enhed, der holder fra Les Films la Boetic (Paris)/Canaria Films (Rom) - the Sundance Kid«. først til sidst. Man er med hele tiden. Italian International Film (Rom). Ex-P: André Ge- Langt mere Hustonsk er de mange noves. P: Guy Azzi. P-leder: Pierre Gauchet. I- Og her er vi måske ved Chabrols ieder: Patrick Delauneux. Instr/Nlanus: Claude pudsige ’tall tales’, der hylder mand- egentlige styrke, der - i hvert fald i Chabrol. Instr-ass: Michel Dupuy, Alain Wermus. folkefornuften på idealismens bekost Foto: Jean Rabier. Kamera: Alain Douarinou/Ass: denne anmelders øjne - langt overskyg Raymond Menvielle, André Marquette. Farve: East- ning og ikke tager for tungt på et par ger, hvad der måtte være af tilløb til mancolor. Klip: Jacques Gaillard, Monique Gail- skurkes død. Der er en klart nostalgisk lard. Ark/Dekor: Guy Littaye. Kost: Karl Lager- filosofisk diskussion i historien: Evnen feld/Ass: Gi I les Dufour. Komp: Pierre Jansen. Dir: stemning omkring de gode gamle selv til at »lade« hvert eneste billede med en André Girard. Tone: Guy Chichignoud, Alex Pront/ tægtstider, som måske skal være svær Ass: Gérard Dacquay. Lyd-E: Louis Devaivre. knitrende, ildevarslende spænding, der Makeup: Alexandre Marcus. Frisurer: Simone at sluge: det er denne tvetydighed, som kalder på sin forløsning, men aldrig får Knapp. Medv: Michel Piccoli (Pierre Maury, vice jeg ikke synes Huston på nogen måde borgmester), Stéphane Audran (Lucienne Dela- gør rede for. Paul Newman vælger brø den helt. -

Techniques and Practical Skills in Scenery, Set Dressing and Decorating for Live-Action Film and Television

International Specialised Skills Institute Inc Techniques and Practical Skills in Scenery, Set Dressing and Decorating for Live-Action Film and Television Julie Belle Skills Victoria/ISS Institute TAFE Fellowship Fellowship funded by Skills Victoria, Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, Victorian Government ISS Institute Inc. APRIL 2010 © International Specialised Skills Institute ISS Institute Suite 101 685 Burke Road Camberwell Vic AUSTRALIA 3124 Telephone 03 9882 0055 Facsimile 03 9882 9866 Email [email protected] Web www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne. ISS Institute 101/685 Burke Road Camberwell 3124 AUSTRALIA April 2010 Also extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. Executive Summary In film and television production, the art department operates, under the leadership of the production designer or art director, to create and manipulate the overall ‘look, feel and mood’ of the production. The appearance of sets and locations transports audiences into the world of the story, and is an essential element in making a production convincing and evocative. -

College Choices for the Visual and Performing Arts 2011-2012

A Complete Guide to College Choices for the Performing and Visual Arts Ed Schoenberg Bellarmine College Preparatory (San Jose, CA) Laura Young UCLA (Los Angeles, CA) Preconference Session Wednesday, June 1 MYTHS AND REALITIES “what can you do with an arts major?” Art School Myths • Lack rigor and/or structure • Do not prepare for career opportunities • No academic challenge • Should be pursued as a hobby, not a profession • Graduates are unemployable outside the arts • Must be famous to be successful • Creates starving artists Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School in the News Visual/Performing Arts majors are the… “Worst-Paid College Majors” – Time “Least Valuable College Majors” – Forbes “Worst College Majors for your Career” – Kiplinger “College Degrees with the Worst Return on Investment” – Salary.com Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School Reality Projected More than 25 28 million in 2013 million in 2020 More than 25 million people are working in arts-related industry. By 2020, this is projected to be more that 28 million – a 15% increase. (U.S. Department of Labor) Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School Reality Due to the importance of creativity in the innovation economy, more people are working in arts than ever before. Copyright: This presentation -

Art Directors Guild to Induct Three Legendary Production Designers Into Its Hall of Fame at 18Th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards February 8, 2014

Art Directors Guild to Induct Three Legendary Production Designers Into Its Hall of Fame at 18th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards February 8, 2014 LOS ANGELES, Sept. 11 — Three legendary Production Designers – Robert Clatworthy, Harper Goff and J. Michael Riva – will be inducted into the Art Directors Guild (ADG) Hall of Fame at the Guild’s 18th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards ceremony to be held at the Beverly Hilton Hotel on February 8, 2014, as announced today by ADG Council Chairman John Shaffner and Awards Producers Raf Lydon and Dave Blass. In making the announcement Shaffner said, “Clatworthy, Goff and Riva join a distinguished group of ADG Hall of Famers, whose collective work parallels the best of motion picture and television production design. They are most worthy and welcomed additions.” Nominations for the 18th Annual ADG Excellence in Production Design Awards will be announced on January 9, 2014. On awards night, February 8, the ADG will present winners in ten competitive categories for theatrical films, television productions, commercials and music videos. Recipient of this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award will be Production Designer and Art Director Rick Carter, as previously announced. The Excellence in Production Design Awards are open only to productions, when made within the U.S., by producers signatory to the IATSE agreement. Foreign entries are acceptable without restrictions. ROBERT CLATWORTHY (1911 – 1992) Robert Clatworthy (William Robert Clatworthy) was an Oscar®-winning American Production Designer who worked at Paramount starting in 1938, and at Universal until 1964. In the 1960’s Clatworthy became involved with some of Hollywood’s best directors, including Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kramer. -

Alvar Aalto. Ken Adam. Ai Weiwei. Doug Aitken. Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Robert Altman

ALVAR AALTO. KEN ADAM. AI WEIWEI. DOUG AITKEN. LAWRENCE ALMA-TADEMA. ROBERT ALTMAN. MARTIN AMIS. MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI.DIANE ARBUS . AUNTIE MAME. ADAM BARTOS.SAUL BASS. FRANCIS BACON. BILLY BALDWIN. MATTHEW BARNEY. BAUHAUS. AUBREY BEARDSLEY. CECIL BEATON. NORMAN BEL GEDDES.WILLIAM BLAKE.RICARDO BOFILL. HIERONYMOUS BOSCH.ETIENNE LOUIS BOULLEE. GUY BOURDIN. DAVID BOWIE. ROBERT.F. BOYLE. JOHN BOX . ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL.HENRY BUMSTEAD.ANTHONY BURGESS. EDWARD BURTYNSKY . JOHN LE CARRE.FRANCOIS CATROUX.NICK CAVE.DAVID CHIPPERFIELD. LYNNE COHEN. JOHN CONSTABLE.BENJAMIN CONSTANT.GREGORY CREWDSON. JACQUES LOUIS-DAVID.EUGENE DELACROIX .THOMAS DEMAND .GUSTAVE DORE .EDMUND DULAC.TONY DUQUETTE. WILLIAM EGGLESTON.OLAFUR ELIASSON. DANTE FERRETTI. IAN FLEMING . FLUX.LUCIEN FREUD.FUTURE SYSTEMS. THEODORE GERICAULT .ALEXANDER GIRARD .NAN GOLDIN.ERNO GOLDFINGER . ANDY GOLDSWORTHY . PETER GREENAWAY. NICHOLAS GRIMSHAW.WALTER GROPIUS .ANDREAS GURSKY. FRANS HALS.ROBERT PARKER HARRISON.HAROLD AND MAUDE.THOMAS HEATHERWICK.DAVID HICKS.TODD HIDO.ALFRED HITCHCOCK . CANDIDA HOFER. WILLIAM HOGARTH. HUNDERTWASSER . AXEL HUTTE. IRATA ISOZAKI. TOYO ITO. ALEJANDRO JADOROWSKY. JEAN –PIERRE JEUNET and MARC CARO. A.QUINCY JONES. LOUIS KHAN.REM KOOLHAAS . STANLEY KUBRICK.KENGO KUMA. HENRI LABROUSTE. MORRIS LAPIDUS .DENYS LASDUN. CLAUDE NICOLAS LEDOUX. MING CHO LEE.SERGIO LEONE. IVAN LEONIDOV .RICHARD LESTER .JEAN –JACQUES LEQUEU .EDWIN LONGSDON LONG.BERTHOLD LUBETKIN..EDWIN LUTYENS.DAVID LYNCH. KAZIMIR MALEVICH .ROB MALLET-STEVENS. THE MAN WHO FELL TO EARTH.ANTHONY MASTERS.SYD MEAD.WILLIAM CAMERON MENZIES.RICHARD MISRACH. DON McCULLIN . MORPHOSIS. VLADEMIR NABAKOV.ODD NERDRUM.PIER LUIGI NERVI.OSCAR NIEMEYER.ANDRE LE NOTRE. MIKE NICHOLS. IRWIN OLAF. ONE FROM THE HEART.GABRIEL OROZCO.BILL OWENS. MARTIN PARR.JOHN PAWSON.CHRISTOPHER PAYNE .PIRANESI.ROBERT POLIDORI.GIO PONTI . -

Oscar®-Nominated Production Designer Jim Bissell to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award at 19Th Annual Art Directors Guild Awards on January 31, 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OSCAR®-NOMINATED PRODUCTION DESIGNER JIM BISSELL TO RECEIVE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT 19TH ANNUAL ART DIRECTORS GUILD AWARDS ON JANUARY 31, 2015 LOS ANGELES, July 15, 2014 — Emmy®-winning and Oscar®-nominated Production Designer Jim Bissell will receive the Art Directors Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award at the 19th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards on January 31, 2015 at a black- tie ceremony at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The announcement was made today by John Shaffner, ADG Council Chairman, and ADG Award Producers Dave Blass and James Pearse Connelly. “Jim Bissell’s work as a Production Designer is legendary and we are proud to rank him among the best in the history of our profession. He is an extraordinary artist and accomplished leader in the industry and it is our pleasure to name him as this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award recipient,” said Shaffner. A veteran leader of the ADG, Bissell was a past Vice President and a Board member for more than 15 years. He also chaired the Guild’s Awards Committee for the first three years of its existence. Bissell’s distinguished work can be seen on such notable films as E.T. the Extra- Terrestrial (1982), which took home four Oscars® with an additional five Oscar® nominations in 1983; The Rocketeer (1991), Jumanji (1995), 300 (2006), Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011) and most recently The Monuments Men (2014), directed by and starring George Clooney. Monuments Men is Jim’s fourth collaboration with Clooney, which began with Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), followed with Oscar®-nominated Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) and continuing with Leatherheads (2007). -

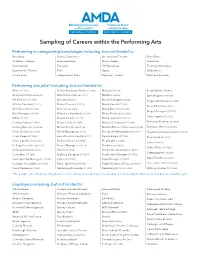

Sampling of Careers Within the Performing Arts

Sampling of Careers within the Performing Arts Performing in categories/places/stages including, but not limited to: Broadway Dance Companies International Theatre Short Films Children’s Theatre Documentaries Music Videos Television Commercials Festivals Off-Broadway Touring Companies Community Theatre Film Opera Web Series Cruise Ships Independent Films Regional Theatre West End London Performing arts jobs* including, but not limited to: Actor (27-2011) Dance Academy Owner (27-2032) Mascot (27-2090) Script Writer (27-3043) Announcer/Host (27-2010) Dance Instructor (25-1121) Model (27-2090) Set Designer (27-1027) Art Director (27-1011) Dancer (27-2031) Music Arranger (27-2041) Singer Songwriter (27-2042) Artistic Director (27-1011) Dialect Coach (25-1121) Music Coach (27-2041) Sound Editor (27-4010) Arts Educator (25-1121) Director (27-2012) Music Director (27-2041) Stage Manager (27-2010) Arts Manager (11-9190) Director’s Assistant (27-2090) Music Producer (27-2012) Talent Agent (27-2012) Ballet (27-2031) Drama Coach (25-1121) Music Teacher (25-1121) Casting Agent (27-2012) Drama Critic (27-3040) Musical Composer (27-2041) Technical Director (27-4010) Casting Director (27-2012) Drama Teacher (25-1121) Musical Theatre Musician (27-2042) Technical Writer (27-3042) Choir Director (27-2040) Event Manager (27-3030) Non-profit Administrator (43-9199) Theatre Company Owner (27-2032) Choir Singer (27-2042) Executive Assistant (43-6011) Opera Singer (27-2042) Tour Guide (39-7011) Choreographer (27-2032) Fashion Model (27-2090) Playwright (27-3043) -

Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign Im Film: Eine Erste Bibliographie 2011

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie 2011 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, Institut für Germanistik 2011 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 122). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12753. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0122_11.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft / Hamburg: Berichte und Papiere 122, 2011: Mode im Film. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Ludger Kaczmarek, Hans J. Wulff. ISSN 1613-7477. URL: http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/Medien/berichte/arbeiten/0122_11.html Letzte Änderung: 20.2.2011. Kleidung / Mode / Couture / Kostümdesign im Film: Eine erste Bibliographie. Zusammengest. v. Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek Inhalt: da, wo die Hobos sind, er riecht wie einer: Also ist er Einleitung einer. Warum sollte man jemanden für einen anderen Bibliographien halten als den, der er zu sein scheint? In Nichols’ Direktoria Working Girl (1988) nimmt eine Sekretärin heimlich Texte für eine Zeit die Rolle ihrer Chefin an, und sie be- nutzt auch deren Garderobe und deren Parfüm. -

Art/Production Design Department Application Requirements

Art/Production Design Department Thank you for your interest in the Art Department of I.A.T.S.E. Local 212. Please take a few moments to read the following information, which outlines department specific requirements necessary when applying to the Art Department. The different positions within the Art/Production Department include: o Production Designer o Art Director (Head of Department) o Assistant Art Director o Draftsperson/Set Designer o Graphic Artist/Illustrator o Art Department Coordinator and o Trainee Application Requirements For Permittee Status In addition to completing the “Permit Information Package” you must meet the following requirement(s): o A valid Alberta driver’s license, o Have a strong working knowledge of drafting & ability to read drawings, o Have three years professional Design training or work experience, o Strong research abilities, o Freehand drawing ability and o Computer skills in Accounting and/or CADD and or Graphic Computer programs. APPLICANTS ARE STRONGLY RECOMMENDED TO HAVE EXPERIENCE IN ONE OR MORE OF THE FOLLOWING AREAS: o Art Departments in Film, Theatre, and Video Production o Design and Design related fields: o Video/Film and Television Art Direction & Staging o Theatrical Stage Design & Technical Direction o Architectural Design & Technology o Interior Design o Industrial Design o Graphic Design o Other film departments with proven technical skills beneficial to the needs of the Art Department. Your training and experience will help the Head of the Department (HOD) determine which position you are best suited for. Be sure to clearly indicate how you satisfy the above requirements. For example, on your resume provide detailed information about any previous training/experience (list supervisor names, responsibilities etc.) Additionally, please provide copies of any relevant licenses, tickets and/or certificates etc. -

Lacon 1 Film Program

BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION This film program represents for the most part an extremely personal selection by me, Bill Warren, with the help of Donald F. Glut. Usually convention film programs tend to show the established classics -- THINGS TO COME, METROPOLIS, WAR OF THE WORLDS, THEM - and, of course, those are good films. But they are seen so very often -- on tv, at non-sf film programs, at regional cons, and so forth -- that we decided to try to organize a program of good and/or entertaining movies that are rarely seen. We feel we have made a good selection, with films chosen for a variety of reasons. Some of the films on the program were, until quite recently, thought to be missing or impossible to view, like JUST IMAGINE, TRANSATLANTIC TUNNEL, or DR JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE. Others, since they are such glorious stinkers, have been relegated to 3 a.m. once-a-year tv showings, like VOODOO MAN or PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE. Other fairly recent movies (and good ones, at that) were, we felt, seen by far too few people, either due to poor distribution by the releasing companies, or because they didn't make enough money to ensure a wide release, like TARGETS or THE DEVIL'S BRIDE. Still others are relatively obscure foreign films, a couple of which we took a sight-unseen gamble on, basing our selections on favorable reviews; this includes films like THE GLADIATORS and END OF AUGUST AT THE HOTEL OZONE. And finally, there are a number of films here which are personal favorites of Don's or mine which we want other people to like; this includes INTERNATIONAL HOUSE, MAD LOVE, NIGHT OF THE HUNTER, RADIO RANCH, and SPY SMASHER RETURNS.