Opera in the Age of Rousseau Music, Confrontation, Realism David Charlton Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis

GOLDFARB, BARRY E., The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' "Alcestis" , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 33:2 (1992:Summer) p.109 The Conflict of Obligations in Euripides' Alcestis Barry E. Goldfarb 0UT ALCESTIS A. M. Dale has remarked that "Perhaps no f{other play of Euripides except the Bacchae has provoked so much controversy among scholars in search of its 'real meaning'."l I hope to contribute to this controversy by an examination of the philosophical issues underlying the drama. A radical tension between the values of philia and xenia con stitutes, as we shall see, a major issue within the play, with ramifications beyond the Alcestis and, in fact, beyond Greek tragedy in general: for this conflict between two seemingly autonomous value-systems conveys a stronger sense of life's limitations than its possibilities. I The scene that provides perhaps the most critical test for an analysis of Alcestis is the concluding one, the 'happy ending'. One way of reading the play sees this resolution as ironic. According to Wesley Smith, for example, "The spectators at first are led to expect that the restoration of Alcestis is to depend on a show of virtue by Admetus. And by a fine stroke Euripides arranges that the restoration itself is the test. At the crucial moment Admetus fails the test.'2 On this interpretation 1 Euripides, Alcestis (Oxford 1954: hereafter 'Dale') xviii. All citations are from this editon. 2 W. D. Smith, "The Ironic Structure in Alcestis," Phoenix 14 (1960) 127-45 (=]. R. Wisdom, ed., Twentieth Century Interpretations of Euripides' Alcestis: A Collection of Critical Essays [Englewood Cliffs 1968]) 37-56 at 56. -

Table 7-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–62

1 Table 12-1 French Opera Repertory 1753–63 (with Court performances of opéras- comiques in 1761–63) See Table 1-1 for the period 1742–52. This Table is an overview of commissions and revivals in the elite institutions of French opera. Académie Royale de Musique and Court premieres are listed separately for each work (albeit information is sometimes incomplete). The left-hand column includes both absolute world premieres and important earlier works new to these theatres. Works given across a New Year period are listed twice. Individual entrées are mentioned only when revived separately, or to avoid ambiguity. Prologues are mostly ignored. Sources: BrennerD, KaehlerO, LagraveTP, LajarteO, Lavallière, Mercure, NG, RiceFB, SerreARM. Italian works follow name forms etc. cited in Parisian libretti. LEGEND: ARM = Académie Royale de Musique (Paris Opéra); bal. = ballet; bouf. = bouffon; CI = Comédie-Italienne; cmda = comédie mêlée d’ariettes; com. lyr. = comédie lyrique; d. gioc.= dramma giocoso; div. scen. = divertimento scenico; FB = Fontainebleau; FSG = Foire Saint-Germain; FSL = Foire Saint-Laurent; hér. = héroïque; int. = intermezzo; NG = The New Grove Dictionary of Music; NGO = The New Grove Dictionary of Opera; op. = opéra; p. = pastorale; Vers. = Versailles; < = extract from; R = revised. 1753 ALL AT ARM EXCEPT WHERE MARKED Premieres at ARM (listed first) and Court Revivals at ARM or Court (by original date) Titon & l’Aurore (p. hér., 3: La Marre, Voisenon, Atys (Lully, 1676) FB La Motte / Mondonville, Jan. 9) Phaëton (Lully, 1683) Scaltra governatrice, La (d. gioc., 3: Palomba / Fêtes Grecques et romaines, Les (Blamont, 1723) Cocchi, Jan. 25) Danse, La (<Fêtes d’Hébé, Les)(Rameau, 1739) FB Jaloux corrigé, Le (op. -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Les Opéras De Lully Remaniés Par Rebel Et Francœur Entre 1744 Et 1767 : Héritage Ou Modernité ? Pascal Denécheau

Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Pascal Denécheau To cite this version: Pascal Denécheau. Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? : Deuxième séminaire de recherche de l’IRPMF : ”La notion d’héritage dans l’histoire de la musique”. 2007. halshs-00437641 HAL Id: halshs-00437641 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00437641 Preprint submitted on 1 Dec 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. P. Denécheau : « Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur : héritage ou modernité ? » Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Une grande partie des œuvres lyriques composées au XVIIe siècle par Lully et ses prédécesseurs ne se sont maintenues au répertoire de l’Opéra de Paris jusqu’à la fin du siècle suivant qu’au prix d’importants remaniements : les scènes jugées trop longues ou sans lien avec l’action principale furent coupées, quelques passages réécrits, un accompagnement de l’orchestre ajouté là où la voix n’était auparavant soutenue que par le continuo. -

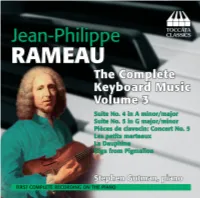

Toccata Classics TOCC0052 Notes

RAMEAU ON THE PIANO, VOLUME THREE 1 by Graham Sadler The two suites recorded on this disc are from the Nouvelles suites de pièces de clavecin of 1729 or 1730, Rameau’s final collection of solo keyboard music.2 Like those of his Pièces de clavessin (1724), they are contrasted both in tonality and character. The Suite in A minor and major is dominated by dances and includes only three character pieces, whereas the Suite in G major and minor consists almost exclusively of pieces with character titles. In its make-up if not its style, the latter thus follows the example of François Couperin, whose first three books of pièces de clavecin (1713, 1717 and 1722) had established the vogue for descriptive pieces. In that sense, Rameau may be regarded as somewhat conservative in devoting half of his two mature solo collections to suites of the more traditional type. Suite No. 4 in A minor and major Conservative they may be, but the dance movements of the Nouvelles suites are among the most highly P developed in the repertory, the first two particularly so. The Allemande 1 unfolds with an effortless grace, its unerring sense of direction reinforced by the many sequential passages. At the end of both sections, the duple semiquaver motion gives way unexpectedly to triplet motion, providing a memorable ‘rhyme’ to the two parts of the movement. The Courante 2, more than twice as long as its predecessors in Rameau’s output, displays a technical sophistication without parallel in the clavecin repertory. Three themes interlock in mainly three- part counterpoint – a bold motif in rising fourths, and two accompanying figures in continuous quavers, the one in sinuous stepwise movement, the other comprising cascading arpeggios. -

Cpo 555 156 2 Booklet.Indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau Pigmalion · Dardanus Suites & Arias Anders J. Dahlin L’Orfeo Barockorchester Michi Gaigg cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 1 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 2 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764) Pigmalion Acte-de-ballet, 1748 Livret by Sylvain Ballot de Sauvot (1703–60), after ‘La Sculpture’ from Le Triomphe des arts (1700) by Houdar de la Motte (1672–1731) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 1 Ouverture 4'41 2 [Air,] ‘Fatal Amour’ (Pigmalion) 3'22 3 Air. Très lent – Gavotte gracieuse – Menuet – Gavotte gai – Chaconne vive – 5'44 Loure – Passepied vif – Rigaudon vif – Sarabande pour la Statue – Tambourin 4 Air gai 2'19 5 Pantomime niaise 0'44 6 2e Pantomime très vive 2'07 7 Ariette, ‘Règne Amour’ (Pigmalion) 4'35 8 Air pour les Graces, Jeux et Ris 0'50 9 Rondeau Contredanse 1'37 cpo 555 156_2 Booklet.indd 3 12.06.2020 09:36:39 Dardanus Tragedie en musique, 1739 (rev. 1744, 1760) Livret by Charles-Antoine Leclerc de La Bruère (1716–54) (selected movements: Suite & Arias) 10 Ouverture 4'13 11 Prologue, sc. 1: Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs [et la Jalousie et sa Suite] 1'06 12 Air pour les [Jeux et les] Plaisirs 1'05 13 Prologue, sc. 2: Air gracieux [pour les Peuples de différentes nations] 1'30 14 Rigaudon 1'41 15 Act 1, sc. 3: Air vif 2'46 16 Rigaudons 1 et 2 3'36 17 Act 2, sc. 1: Ritournelle vive 1'08 18 Act 4, sc. -

| 216.302.8404 “An Early Music Group with an Avant-Garde Appetite.” — the New York Times

“CONCERTS AND RECORDINGS“ BY LES DÉLICES ARE JOURNEYS OF DISCOVERY.” — NEW YORK TIMES www.lesdelices.org | 216.302.8404 “AN EARLY MUSIC GROUP WITH AN AVANT-GARDE APPETITE.” — THE NEW YORK TIMES “FOR SHEER STYLE AND TECHNIQUE, LES DÉLICES REMAINS ONE OF THE FINEST BAROQUE ENSEMBLES AROUND TODAY.” — FANFARE “THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES ARE FIRST CLASS MUSICIANS, THE ENSEMBLE Les Délices (pronounced Lay day-lease) explores the dramatic potential PLAYING IS IRREPROACHABLE, AND THE and emotional resonance of long-forgotten music. Founded by QUALITY OF THE PIECES IS THE VERY baroque oboist Debra Nagy in 2009, Les Délices has established a FINEST.” reputation for their unique programs that are “thematically concise, — EARLY MUSIC AMERICA MAGAZINE richly expressive, and featuring composers few people have heard of ” (NYTimes). The group’s debut CD was named one of the "Top “DARING PROGRAMMING, PRESENTED Ten Early Music Discoveries of 2009" (NPR's Harmonia), and their BOTH WITH CONVICTION AND MASTERY.” performances have been called "a beguiling experience" (Cleveland — CLEVELANDCLASSICAL.COM Plain Dealer), "astonishing" (ClevelandClassical.com), and "first class" (Early Music America Magazine). Since their sold-out New “THE CENTURIES ROLL AWAY WHEN York debut at the Frick Collection, highlights of Les Délices’ touring THE MEMBERS OF LES DÉLICES BRING activites include Music Before 1800, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner THIS LONG-EXISTING MUSIC TO Museum, San Francisco Early Music Society, the Yale Collection of COMMUNICATIVE AND SPARKLING LIFE.” Musical Instruments, and Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Les — CLASSICAL SOURCE (UK) Délices also presents its own annual four-concert series in Cleveland art galleries and at Plymouth Church in Shaker Heights, OH, where the group is Artist in Residence. -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck -

Castanets 1 Castanets

Castanets 1 Castanets Castanet(s) Castanets Percussion instrument Classification hand percussion Hornbostel–Sachs classification 111.141 (Directly struck concussive idiophone) Castanets are a percussion instrument (idiophone), used in Moorish, Ottoman, ancient Roman, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese music. The instrument consists of a pair of concave shells joined on one edge by a string. They are held in the hand and used to produce clicks for rhythmic accents or a ripping or rattling sound consisting of a rapid series of clicks. They are traditionally made of hardwood, although fibreglass is becoming increasingly popular. In practice a player usually uses two pairs of castanets. One pair is held in each hand, with the string hooked over the thumb and the castanets resting on the palm with the fingers bent over to support the other side. Each pair will make a sound of a slightly different Castanets seller in Granada, Spain pitch. The origins of the instrument are not known. The practice of clicking hand-held sticks together to accompany dancing is ancient, and was practised by both the Greeks and the Egyptians. In more modern times, the bones and spoons used in Minstrel show and jug band music can also be considered forms of the castanet. When used in an orchestral setting, castanets are sometimes attached to a handle, or mounted to a base to form a pair of machine castanets. This makes them easier to play, but also alters the sound, particularly for the machine castanets. It is possible to produce a roll on a pair of castanets in any of the three ways in Castanets 2 which they are held. -

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PAUL SCOTT, University of Kansas

THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PAUL SCOTT, University of Kansas 1. GENERAL Orientalism and discussions of identity and alterity form part of an identifiable trend in our field during the coverage of the two calendar years. Another strong current is the concept of libertinage and its literary and social influence. In terms of the first direction, Nicholas Dew, Orientalism in Louis XlV's France, OUP, 2009, xv+301 pp., publishes an overview of what he terms 'baroque Orientalism' and explores the topos through chapters devoted to the production of texts by d'Herbelot, Bernier, and Thevenot which would have an important reception and influence during the 18th century. The network of the Republic of Letters was crucial in gaining access to and studying oriental works and, while this was a marginal presence during the period, D. reveals how the curiosity of vth-c. scholars would lay the foundations of work that would be drawn on by the philosophes. Duprat, Orient, is an apt complement to Dew's volume, and A. Duprat, 'Le fil et la trame. Motifs orientaux dans les litteratures d'Europe' (9-17) maintains that the depiction of the Orient in European lit. was a common attempt to express certain desires but, at the same time, to contain a general angst as a result of incorporating scientific progress and territorial expansion. Brian Brazeau, Writing a New France, 1604-1632: Empire and Early Modern French Identity, Farnham, Ashgate, 2009, x +132 pp., selects the period following the end of the Wars of Religion because this early period of colonization gave rise to some of the most enthusiastic accounts as well as the fact that they established the pioneering debate for future narratives. -

Dardanus De Jean-Philippe Rameau Direction Musicale Emmanuelle Haïm Mise En Scène Claude Buchvald Chorégraphie Daniel Larrieu Chœur Et Orchestre Du Concert D’Astr Ée

Dossier pédagogique Opéra / Nouvelle production DARDANUS DE JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU DIRECTION MUSICALE EMMANUELLE HAÏM MISE EN SCÈNE CLAUDE BUCHVALD CHORÉGRAPHIE DANIEL LARRIEU CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE DU CONCERT D’ASTR ÉE Du 16 au 24 octobre 2009 Contacts Service des relations avec les publics [email protected] Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration de Sébastien Bouvier, enseignant missionné à l’Opéra de Lille Septembre 2009 Sommaire Préparer votre venue à l’Opéra 3 DARDANUS Résumé 4 Synopsis 5 La musique baroque 6 La tragédie lyrique ou « tragédie en musique » 7 Les instruments baroques 10 La danse dans l’opéra baroque 12 Guide d’écoute 14 Vocabulaire 21 Références 22 DARDANUS À L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Distribution 23 Notes d’intention de mise en scène 24 Repères biographiques 25 POUR ALLER PLUS LOIN La Voix à l’opéra 27 Qui fait quoi à l’opéra ? 29 L’Opéra de Lille, un lieu, une histoire 30 ANNEXES Les instruments de l’orchestre 34 Annexe : frise chronologique sur Rameau et son époque 35 2 Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - lire la fiche résumé et le synopsis détaillé - faire une écoute des extraits représentatifs de l’opéra (guide d’écoute) Recommandations Le spectacle débute à l’heure précise, 20h ou 16h le dimanche. Il est donc impératif d’arriver au moins 30 minutes à l’avance, les portes sont fermées dès le début du spectacle. -

Redalyc.Recueil D'anecdotes Musicales Du Xviiie Siècle

Çedille. Revista de Estudios Franceses E-ISSN: 1699-4949 [email protected] Asociación de Francesistas de la Universidad Española España Abramovici, Jean Christophe; Sanz, Teo Recueil d'anecdotes musicales du XVIIIe siècle Çedille. Revista de Estudios Franceses, núm. 3, abril, 2007, pp. 19-33 Asociación de Francesistas de la Universidad Española Tenerife, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80800304 Comment citer Numéro complet Système d'Information Scientifique Plus d'informations de cet article Réseau de revues scientifiques de l'Amérique latine, les Caraïbes, l'Espagne et le Portugal Site Web du journal dans redalyc.org Projet académique sans but lucratif, développé sous l'initiative pour l'accès ouverte ISSN: 1699-4949 nº 3, abril de 2007 Monografía La anécdota en el siglo XVIII Recueil d’anecdotes musicales du XVIIIe siècle* Jean-Christophe Abramovici Université de Valenciennes [email protected] Teo Sanz Universidad de Burgos [email protected] 1. Sur la musique, les ballets, les concerts et les spectacles musicaux en général: En 1722, le régent et ses compagnons de débauches célébraient des orgies qu’ils appelaient fêtes d’Adam. Laissons parler le duc de Richelieu, qui sans doute y assistait (...). «D’autres fois, on choisissait les plus beaux jeunes gens de l’un et de l’autre sexe qui dansaient à l’Opéra, pour répéter des ballets que le ton aisé de la société, pendant la régence, avait rendus si lascifs, et que ces gens exécutaient dans cet état primitif où étaient les hommes avant qu’ils connussent les voiles et les vêtements. Ces orgies, que le régent, Dubois et ses roués appelaient fêtes d’Adam, furent répétées une douzaine de fois; car le prince parut s’en dégoûter» (Dulaure, III, 493-494).