THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY PAUL SCOTT, University of Kansas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inventory of Botanical Curiosities in Pierre-François-Xavier

O inventário das curiosidades botânicas da Nouvelle France de Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix (1744) KOBELINSKI, Michel. O inventário das curiosidades botânicas da Nouvelle France de Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix (1744). História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.20, n.1, jan.-mar. 2013, p.13-27. O inventário das Resumo Verifica a extensão dos aportes botânicos curiosidades botânicas de Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix em Histoire et description générale de la da Nouvelle France de Nouvelle France em relação a trabalhos de pesquisadores anteriores, suas valorações Pierre-François-Xavier das representações iconográficas e discursivas e aplicabilidade no projeto de Charlevoix (1744) de colonização francesa. Investiga- se o que o levou a preterir o modelo taxionômico de Lineu e o que pretendia com seu catálogo de curiosidades The inventory of botânicas. O desenlace de sua trajetória filosófico-religiosa permite compreender botanical curiosities in seu posicionamento no quadro de classificação da natureza, os sentidos Pierre-François-Xavier das informações etnológicas, as formas de apropriação intelectual e os usos de Charlevoix’s Nouvelle da iconografia botânica e do discurso como propaganda político-emotiva para France (1744) incentivar a ocupação colonial. Palavras-chave: história do Canadá; história e sensibilidades; história e natureza; Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix (1682-1761); botânica. Abstract The article explores the botanical contributions of Pierre-François-Xavier de Charlevoix’s book Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle France vis-à-vis the contributions of previous researchers, his use of iconographic and discursive representations and its relevance to the project of French colonization. It investigates why he refused Linnaeus’ taxonomic model and what he intended with his catalogue of botanical curiosities. -

Les Opéras De Lully Remaniés Par Rebel Et Francœur Entre 1744 Et 1767 : Héritage Ou Modernité ? Pascal Denécheau

Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Pascal Denécheau To cite this version: Pascal Denécheau. Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? : Deuxième séminaire de recherche de l’IRPMF : ”La notion d’héritage dans l’histoire de la musique”. 2007. halshs-00437641 HAL Id: halshs-00437641 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00437641 Preprint submitted on 1 Dec 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. P. Denécheau : « Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur : héritage ou modernité ? » Les opéras de Lully remaniés par Rebel et Francœur entre 1744 et 1767 : héritage ou modernité ? Une grande partie des œuvres lyriques composées au XVIIe siècle par Lully et ses prédécesseurs ne se sont maintenues au répertoire de l’Opéra de Paris jusqu’à la fin du siècle suivant qu’au prix d’importants remaniements : les scènes jugées trop longues ou sans lien avec l’action principale furent coupées, quelques passages réécrits, un accompagnement de l’orchestre ajouté là où la voix n’était auparavant soutenue que par le continuo. -

Dossier De Presse

Atypik Films Présente Patrick Ridremont François Berléand Virginie Efira DEAD MAN TALKING Un film belge de PATRICK RIDREMONT (Durée : 1h41) Distribution Relations Presse Atypik Films Laurence Falleur Communication 31 rue des Ombraies 57 rue du Faubourg Montmartre 92000 Nanterre 75009 Paris Eric Boquého Laurence Falleur Assisté de Sandrine Becquart Assisté de Vincent Bayol Et Jacques Domergue Tel : 01.83.92.80.51 Tel : 01.77.68.32.16. Port. : 06.48.89.41.29 Port. : 06.62.49.19.87. [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Matériel de presse téléchargeable sur www.atypikfilms.com SYNOPSIS William Lamers , 40 ans, anonyme criminel condamné au Poison pour meurtre, se prépare à être exécuté. La procédure se passe dans l’indifférence générale et, ni la famille du condamné, ni celle de ses victimes n’a fait le déplacement pour assister à l’exécution. Seul le journaliste d’un minable tabloïd local est venu assister au «spectacle». Pourtant ce qui ne devait être qu’une formalité va rapidement devenir un véritable cauchemar pour Karl Raven, le directeur de la prison. Alors qu’on lui demande s’il a quelque chose à dire avant de mourir, William se met à raconter sa vie, et se lance dans un récit incroyable et bouleversant. Raven s’impatiente et appelle le Gouverneur Brodeck pour obtenir l'autorisation d'exécuter William. Mais comme la loi ne précise rien sur la longueur des dernières paroles et que le Gouverneur Stieg Brodeck, au plus bas dans les sondages, ne peut prendre aucun risque à un mois des élections, on décide de laisser William raconter son histoire jusqu’au bout. -

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017

Course Catalogue 2016 /2017 1 Contents Art, Architecture, Music & Cinema page 3 Arabic 19 Business & Economics 19 Chinese 32 Communication, Culture, Media Studies 33 (including Journalism) Computer Science 53 Education 56 English 57 French 71 Geography 79 German 85 History 89 Italian 101 Latin 102 Law 103 Mathematics & Finance 104 Political Science 107 Psychology 120 Russian 126 Sociology & Anthropology 126 Spanish 128 Tourism 138 2 the diversity of its main players. It will thus establish Art, Architecture, the historical context of this production and to identify the protagonists, before defining the movements that Music & Cinema appear in their pulse. If the development of the course is structured around a chronological continuity, their links and how these trends overlap in reality into each IMPORTANT: ALL OUR ART COURSES ARE other will be raised and studied. TAUGHT IN FRENCH UNLESS OTHERWISE INDICATED COURSE CONTENT : Course Outline: AS1/1b : HISTORY OF CLASSIC CINEMA introduction Fall Semester • Impressionism • Project Genesis Lectures: 2 hours ECTS credits: 3 • "Impressionist" • The Post-Impressionism OBJECTIVE: • The néoimpressionnism To discover the great movements in the history of • The synthetism American and European cinema from 1895 to 1942. • The symbolism • Gauguin and the Nabis PontAven COURSE PROGRAM: • Modern and avantgarde The three cinematic eras: • Fauvism and Expressionism Original: • Cubism - The Lumière brothers : realistic art • Futurism - Mélies : the beginnings of illusion • Abstraction Avant-garde : - Expressionism -

Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre De L'odéon- 6E

de Molière 17 septembre 25 octobre 2008 mise en scène & scénographie Stéphane Braunschweig Théâtre de l'Odéon- 6e costumes Thibault Vancraenenbroeck lumière Marion Hewlett son Xavier Jacquot collaboration artistique Anne-Françoise Benhamou collaboration à la scénographie Alexandre de Darden production Théâtre national de Strasbourg créé le 29 avril 2008 au Théâtre national de Strasbourg avec Monsieur Loyal : Jean-Pierre Bagot Cléante : Christophe Brault Tartuffe : Clément Bresson Valère : Thomas Condemine Orgon : Claude Duparfait Mariane : Julie Lesgages Elmire : Pauline Lorillard Dorine : Annie Mercier Damis : Sébastien Pouderoux Madame Pernelle : Claire Wauthion et avec la participation de l’exempt : François Loriquet Rencontre Spectacle du mardi au samedi à 20h, le dimanche à 15h, relâche le lundi Au bord de plateau jeudi 2 octobre Prix des places : 30€ - 22€ - 12€ - 7,50€ (séries 1, 2, 3, 4) à l’issue de la représentation, Tarif groupes scolaires : 11€ et 6€ (séries 2 et 3) en présence de l’équipe artistique. Entrée libre. Odéon–Théâtre de l’Europe Théâtre de l’Odéon Renseignements 01 44 85 40 90 e Place de l’Odéon Paris 6 / Métro Odéon - RER B Luxembourg L’équipe des relations avec le public : Scolaires et universitaires, associations d’étudiants Réservation et Actions pédagogiques Christophe Teillout 01 44 85 40 39 - [email protected] Emilie Dauriac 01 44 85 40 33 - [email protected] Dossier également disponible sur www.theatre-odeon.fr Certaines parties de ce dossier sont tirées du dossier pédagogique et du programme réalisés par l’équipe du Théâtre national de Strasbourg. Collaboration d’Arthur Le Stanc Tartuffe / 17 septembre › 25 octobre 2008 1 Oui, je deviens tout autre avec son entretien, Il m'enseigne à n'avoir affection pour rien ; De toutes amitiés il détache mon âme ; Et je verrais mourir frère, enfants, mère, et femme, Que je m'en soucierais autant que de cela. -

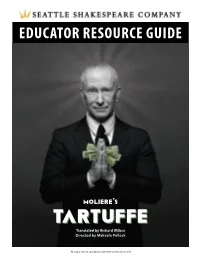

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

MILLER, CHRISTOPHER L. the French Atlantic Triangle: Literature and Culture of the Slave Trade

Universidade Estadual de Goiás Building the way - Revista do Curso de Letras da UnU-Itapuranga THERE ARE NO SLAVES IN FRANCE!?! MILLER, CHRISTOPHER L. The French Atlantic Triangle: Literature and Culture of the Slave Trade. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2010, 572 p. ISBN: 9780822341512. Thomas Bonnici Departamento de Letras / Universidade Estadual de Maringá The history of the 20 th century has shown how difficult it is for a nation to accept its past and to come to terms with shameful and degrading events practiced in centuries gone by. If even mere apologies are not easily wrenched from post-war Spain and Germany, Australia and New Zealand and the treatment of the Aborigines and Maoris, Latin America and its dictatorship periods, South Africa and its Apartheid policies, just to mention a few, can one imagine the healing processes required for more in-depth reconciliation? More than two hundred years had to pass so that whole nations would grapple with their slave-haunted history. London, Bristol, Birmingham and other British cities are only now accepting their long-term involvement with slavery, the slave trade, transatlantic economy, plantation system, enrichment on slave-produced goods. And Africa has still a lot of research to undertake to understand its almost endemic participation in different slave trades and in the selling of its children to Europeans. If Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Britain and Brazil are highly touchy on what they consider a taboo subject, how does France fare in the fray with more than one million Africans in 3,649 recorded trans-Atlantic voyages sent to its Caribbean colonies of Martinique (1635), Guadeloupe (1635), Guyane (1663) and Saint-Domingue / Haiti (1697) during from the 17 th to the early 19 th centuries? Christopher Miller, professor of African-American Studies and French at Yale University, provides readers interested in the history of slavery within the context of literature with a breakthrough book. -

Exoticism and the Jew: Racine's Biblical Tragedies by Stanley F

Exoticism and the Jew: Racine's Biblical Tragedies by Stanley F. Levine pour B. Ponthieu [The Comedie franchise production of Esther (1987) delighted and surprised this spectator by the unexpected power of the play itself as pure theater, by the exotic splendor of the staging, with its magnificent gold and blue decor and the flowing white robes of the Israelite maidens, and most particularly by the insistent Jewish references, some of which seemed strikingly contemporary. That production underlies much of this descussion of the interwoven themes of exoticism and the Jewish character as they are played out in Racine's two final plays.] Although the setting for every Racinian tragedy was spatially or temporally and culturally removed from its audience, the term "exotic" would hardly be applied to most of them. With the exception of Esther and Athalie, they lack the necessary 'local color' which might give them the aura of specificity.1 The abstract Greece of Andromaque or Phedre, for example, pales in comparison with the more circumstantial Roman world of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and Titus Andronicus, to say nothing of the lavish sensual Oriental Egypt in which Gautier's Roman de la Momie luxuriates. To be sure, there are exotic elements, even in Racine's classical tragedies: heroes of Greco-Roman history and legend, melifluous place and personal names ("la fille de Minos et de Pasiphae"), strange and barbaric customs (human sacrifice in Iphigenie). Despite such features, however, the essence of these plays is ahistorical. Racine's Biblical tragedies present a far different picture. Although they may have more in common 52 STANLEY F. -

A History of Women's Political Thought in Europe, 1400-1700

This page intentionally left blank A HISTORY OF WOMEN’S POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EUROPE, 1400–1700 This ground-breaking book surveys the history of women’s political thought in Europe, from the late medieval period to the early modern era. The authors examine women’s ideas about topics such as the basis of political authority, the best form of political organisation, justifications of obedience and resistance, and concepts of liberty, toleration, sociability, equality, and self-preservation. Women’s ideas concerning relations between the sexes are discussed in tandem with their broader political outlooks; the authors demonstrate that the development of a distinctively sexual politics is reflected in women’s critiques of marriage, the double standard, and women’s exclusion from government. Women writers are also shown to be indebted to the ancient idea of political virtue, and to be acutely aware of being part of a long tradition of female political commentary. This work will be of tremendous interest to political philosophers, historians of ideas, and feminist scholars alike. jacqueline broad is an Honorary Research Associate in the School of Philosophy and Bioethics at Monash University. She is author of Women Philosophers of the Seventeenth Century (2002) and co-editor with Karen Green of Virtue, Liberty, and Toleration: Political Ideas of European Women, 1400–1800 (2007). karen green is Associate Professor in the School of Philosophy and Bioethics at Monash University. She is author of Dummett: Philosophy of Language (2001) and The Woman of Reason (1995). A HISTORY OF WOMEN’S POLITICAL THOUGHT IN EUROPE, 1400–1700 JACQUELINE BROAD AND KAREN GREEN Monash University CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521888172 © Jacqueline Broad and Karen Green 2009 This publication is in copyright. -

The French Language in the Digital Age

White Paper Series Collection de Livres Blancs THE FRENCH LA LANGUE LANGUAGE IN FRANÇAISE THE DIGITAL À L’ÈRE DU AGE NUMÉRIQUE Joseph Mariani Patrick Paroubek Gil Francopoulo Aurélien Max François Yvon Pierre Zweigenbaum White Paper Series Collection de Livres Blancs THE FRENCH LA LANGUE LANGUAGE IN FRANÇAISE THE DIGITAL À L’ÈRE DU AGE NUMÉRIQUE Joseph Mariani IMMI-CNRS & LIMSI-CNRS Patrick Paroubek LIMSI-CNRS Gil Francopoulo IMMI-CNRS & TAGMATICA Aurélien Max LIMSI-CNRS & U. Paris Sud 11 François Yvon LIMSI-CNRS & U. Paris Sud 11 Pierre Zweigenbaum LIMSI-CNRS Georg Rehm, Hans Uszkoreit (Éditeurs, editors) PRÉFACE PREFACE Ce livre blanc fait partie d’une collection qui a pour ob- is white paper is part of a series that promotes jectif de faire connaître le potentiel des technologies de knowledge about language technology and its poten- la langue. Il s’adresse en particulier aux journalistes, po- tial. It addresses journalists, politicians, language com- liticiens, communautés linguistiques, enseignants mais munities, educators and others. e availability and aussi à tous. La disponibilité et l’utilisation des techno- use of language technology in Europe vary between logies de la langue variant grandement d’une langue à languages. Consequently, the actions that are required l’autre en Europe, les actions nécessaires au soutien des to further support research and development of lan- activités de recherche et développement peuvent être guage technologies also differ. e required actions très différentes en fonction des langues selon des fac- depend on many factors, such as the complexity of a teurs multiples, comme leur complexité intrinsèque ou given language and the size of its community. -

Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy

Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy EILEEN O’NEILL It has now been more than a dozen years since the Eastern Division of the APA invited me to give an address on what was then a rather innovative topic: the published contributions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century women to philosophy.1 In that address, I highlighted the work of some sixty early modern women. I then said to the audience, “Why have I presented this somewhat interesting, but nonetheless exhausting . overview of seventeenth- and eigh- teenth-century women philosophers? Quite simply, to overwhelm you with the presence of women in early modern philosophy. It is only in this way that the problem of women’s virtually complete absence in contemporary histories of philosophy becomes pressing, mind-boggling, possibly scandalous.” My presen- tation had attempted to indicate the quantity and scope of women’s published philosophical writing. It had also suggested that an acknowledgment of their contributions was evidenced by the representation of their work in the scholarly journals of the period and by the numerous editions and translations of their texts that continued to appear into the nineteenth century. But what about the status of these women in the histories of philosophy? Had they ever been well represented within the histories written before the twentieth century? In the second part of my address, I noted that in the seventeenth century Gilles Menages, Jean de La Forge, and Marguerite Buffet produced doxogra- phies of women philosophers, and that one of the most widely read histories of philosophy, that by Thomas Stanley, contained a discussion of twenty-four women philosophers of the ancient world. -

On Philosophical Style Virpi Lehtinen

On Philosophical Style Virpi Lehtinen To cite this version: Virpi Lehtinen. On Philosophical Style. European Journal of Women’s Studies, SAGE Publications (UK and US), 2007, 14 (2), pp.109-125. 10.1177/1350506807075817. hal-00571300 HAL Id: hal-00571300 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00571300 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On Philosophical Style Michèle Le Dœuff and Luce Irigaray Virpi Lehtinen UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI ABSTRACT Irigaray and Le Dœuff diagnose the problem of woman and philosophy in terms of love. The differing solutions to the problem can be found in their styles. Irigaray’s style is loving and dialogic, transforming the inherent structure of love and reminding us of the traditional feminine position defined by men. Le Dœuff’s style is critical and pluralistic and relates to her perception of the feminine way of philosophical writing. These styles take into account the undervaluation of the feminine in the apparently ‘neutral’ practices of philosophizing and surpass the traditional or unreflected notions of the feminine style. Ultimately, the con- sciously ‘subjective’ styles, with the inherent aims of self-reflectivity and openness for other persons and texts, prove necessary when striving for truth and objectiv- ity.