National Spatial Strategy Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrimoine Mondial 23 COM

Patrimoine Mondial 23 COM Distribution limitée WHC-99/CONF.209/10 Paris, le 5 octobre 1999 Original : anglais / français ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Vingt-troisième session Marrakech, Maroc 29 novembre – 4 décembre 1999 Point 8 de l’ordre du jour provisoire : Informations sur les listes indicatives et examen de propositions d’inscription de biens culturels et naturels sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril et la Liste du patrimoine mondial RESUME 1. A sa dix-septième session à Carthagène, en décembre 1993, le Comité a exprimé sa préoccupation quant au petit nombre de listes indicatives qui répondaient aux exigences stipulées aux paragraphes 7 et 8 des Orientations, et il a confirmé l'importance de ces listes pour la planification, l'analyse comparative des propositions d'inscription et la réalisation des études globales et thématiques. Ces listes constituent en outre un inventaire des biens situés sur le territoire de chaque Etat partie que ce dernier considère comme susceptibles d'être inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. Le Comité a également confirmé que les listes indicatives sont obligatoires pour les biens culturels pour lesquels les Etats parties ont l'intention de soumettre des propositions d'inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial dans les cinq à dix prochaines années. 2. En conséquence, le Comité a invité les Etats parties qui ne l'avaient pas encore fait, à soumettre leurs listes indicatives conformément aux Orientations, étant entendu qu’ "une assistance préparatoire sera fournie si nécessaire et à la demande de l'Etat partie concerné". -

Cost-Loss Analysis and Probabilistic Information for Water Boards

Cost-Loss analysis and probabilistic information for water boards Laura Janssen KNMI Internal Report IR-2015-03 Master Thesis Mathematics Cost-Loss analysis and probabilistic information for water boards Author: Supervisor Radboud University: Laura Janssen Prof. Dr. Ir. Egbert-Jan Sol [email protected] [email protected] Supervisors KNMI: Drs. Kees Kok [email protected] Dr. Maurice Schmeits [email protected] Second reader: Dr. Heleen de Coninck [email protected] July 7, 2015 Abstract The water board Wetterskip Frysl^anin the province Friesland is responsible for managing the water level in the Frisian belt canal system. When the expected water level there, calculated by among others the expected precipitation, is too high, the water board intervenes by opening sluices and operating pumps. To know the expected water level in the Frisian belt canal system, the precipitation forecast must be as accurate as possible. Expected precipitation based on probabilistic information takes uncertainty into account, in contrast to the use of deterministic information, which may lead to better decisions also for the short term, forecasts up to two days ahead. To investigate that, a strategy for a simplified model of the water board is constructed to give a suggestion at which hours sluices may need to be opened and a pump may need to operate if the water level reaches a certain threshold. The input of the strategy consists of precipitation data in Friesland from winters of 2012 to 2015. This thesis compares the output based on probabilistic information, which differs for different water level thresholds, with the output based on deterministic information. -

Obtaining World Heritage Status and the Impacts of Listing Aa, Bart J.M

University of Groningen Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing Aa, Bart J.M. van der IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Aa, B. J. M. V. D. (2005). Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 30-09-2021 Appendix 1 List of interviewed organisations Pilot studies Nr. -

This Work Was Prepared As Part of the Activities Described in the Approved

This work was prepared as part of the activities described in the approved European program Erasmus+ School Key Action 2—Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices- Strategic Partnerships for school education Name of the project: UNESCO Heritage, 2014-2016 Code: 2014-1-RO01- KA201-002437_6. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. This project is funded by the European Union Summary I. LEARNING AND TEACHING FOR FUTURE BY PAST AND PRESENT I.1. A new curriculum, the birth of the area related to History and Local Heritage-Portuguese experience..1 I.2. European Identity and the emergence of Europe and the European civilization ……………………….5 I.3. The Need of World Heritage Education………………………………………………………………..10 I.4. Integration of Word Heritage Education into curricular aproch………………………………………..11 I.5. Reasons for a curriculum proposal………………………………………………………………….….16 I.6. General Competencies……………………………………………….…………………………………18 I.7. Values and attitudes…………………………………………………………………………………….18. I.8. Specific competences and content……………………………………………………………………...20 I.9.Standard performances………………………………………………….………………………………30. II. METHOLOGICAL SUGESTIONS ......................................................................................................32 ANNEXES: Annex 1: Bread in various cultures, an essential constituent of European everyday life…………….……38 Annex 2: Widely used given European common names………………………………………………..….49 Annex 3: The principles of democracy…………………………………………………………….……….58 Annex 4: The €20…………………………………………………………………………………….……..60 Annex 5: European countries-database…………………………………………….…………………….....62 ‘We are not bringing together states, we are uniting people’ Jean Monnet, 1952 EUROPEAN IDENTITY-A PART OF WORLD HERITAGE I. -

De Waddenzee Ir. D.F. Woudagemaal De Stelling

nederlands werelderfgoed Het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden heeft tien door UNESCO erkende werelderfgoederen. Deze zijn uniek in de wereld. de waddenzee ir. d.f. woudagemaal schokland en droogmakerij de stelling van Ze vertellen het bijzondere verhaal van het Koninkrijk der De Waddenzee – uniek in de wereld! De Waddenzee in Nederlanden op het gebied van waterbeheer (water ), omgeving de beemster amsterdam Nederland, Duitsland en Denemarken is een ongeëvenaard burgersamenleving (social ) en (land)ontwerp dynamisch landschap. Nergens ter wereld kom je zo’n Magistrale beleving van stoom, architectuur en water, Schokland is een eiland op het droge, dat rijk is aan Droogmakerij de Beemster in Noord-Holland is sinds Deze 135 kilometer lange, cirkelvormige verdedigings- (design ). uitgestrekt en gevarieerd gebied tegen, ontstaan onder het Ir. D.F. Woudagemaal in Lemmer is het grootste nog archeologische bodemschatten. Schokland herbergt 1999 werelderfgoed. Deze 17e-eeuwse droogmakerij linie rondom Amsterdam bestaat uit sluizen, dammen invloed van eb en vloed en waar veranderingen dagelijks functionerende stoomgemaal ter wereld. Bij een hoge Nederlands langste bewonersgeschiedenis en symboli- werd gerealiseerd om een bedreigend binnenwater om en maar liefst 42 forten en 4 batterijen en werd in 1996 Naast de huidige werelderfgoederen is er ook een merkbaar zijn. Een uitgebreid stelsel van geulen en prielen waterstand zorgt het nog altijd voor droge voeten seert de eeuwenoude strijd van de Nederlanders tegen te zetten in vruchtbare en winstgevende landbouwgrond op de UNESCO Werelderfgoedlijst geplaatst. De Stelling, voorlopige lijst met Nederlands erfgoed dat op de wordt afgewisseld door droogvallende zandplaten. Je vindt in Friesland. Het gemaal is in 1920 geopend door het water. -

Obtaining World Heritage Status and the Impacts of Listing Aa, Bart J.M

University of Groningen Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing Aa, Bart J.M. van der IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Aa, B. J. M. V. D. (2005). Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 04-10-2021 Chapter 3 Nominating world heritage sites Which sites are nominated for the world heritage list largely depends upon who takes the initiative. -

Patrimoine Mondial 23BUR

Patrimoine Mondial 23BUR Distribution limitée WHC-99/CONF.204/ 6 Paris, le 1 avril 1999 Original : Anglais / Français ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL BUREAU DU COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Vingt-troisième session Paris, Siège de l’UNESCO, Salle X 5 - 10 juillet 1999 Point 5 de l'ordre du jour provisoire : Informations sur les listes indicatives et examen des propositions d’inscription de biens culturels et naturels sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril RESUME 1. A sa dix-septième session à Carthagène, en décembre 1993, le Comité a exprimé sa préoccupation quant au petit nombre de listes indicatives qui répondaient aux exigences stipulées aux paragraphes 7 et 8 des Orientations. Il a confirmé l’importance de ces listes à des fins de planification, d'analyse comparative des propositions d'inscription et pour faciliter la réalisation des études globales et thématiques. Ces listes constituent également un inventaire des biens situés sur le territoire de chaque Etat partie et que celui-ci considère comme pouvant être inclus sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial. Le Comité a également confirmé que les listes indicatives étaient obligatoires pour les biens culturels que l’Etat partie a l’intention de proposer pour inscription sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial durant les cinq à dix années à venir. 2. En conséquence, le Comité a invité les Etats parties, qui ne l’auraient pas fait, à soumettre des listes indicatives conformément aux Orientations, étant entendu "qu'une assistance préparatoire sera fournie quand ce sera nécessaire et à la requête de l'Etat partie concerné". -

Bulletin 6 – Autumn 1999

BULLETIN No. 6 ● Autumn 1999 nation-al sector at the Berlin 1999 International Tourism Fair. Opinion The project is led by the Association of Municipalities of the Ruhr Region, in collaboration with the German Society for In- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Industriekultur dustrial Culture of Duisburg. Dr. Wolfgang Ebert The Government of Nordrhein-Westfalen and the European Union supported the project with a substantial investment. The Ruhr District is the most important example of an industrial The tourist economy is displaying considerable growth rates landscape from the peak period of industrialisation. This urban in the Ruhr Region. On the basis of regional structural policy, agglomeration of 6.5 million inhabitants is characterised the tourist profile of the Ruhr Region is to be more sharply de- particularly by the large-scale plants of the mining industry. In fined with the Industrial Culture Route and an economic policy the last 20 years the efforts to maintain a landscape constitut- impulse will be given. ing a monument to the industrial culture were very successful. It was now time to equip it also as an area of tourist interest in Further extension is planned. In the next few years, a ‘visitor such a way that visitors and inhabitants of the region find good mine’ will explain to visitors, at a depth of 1000 metres, the ar- routes and ample information. duous work of the colliery. An important additional step will be represented by the imminent inclusion into the UNESCO World The Industrial Culture Route offers a core network made up of Cultural Heritage List of the colliery landscape surrounding the 19 so-called ‘anchor points’, representing the region’s most Zollverein mine in Essen. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Agriculture's Role as an Upholder of Cultural Heritage Report from a Workshop Karoline Daugstad (ed.) TemaNord 2005:576 Agriculture's Role as an Upholder of Cultural Heritage Report from a Workshop TemaNord 2005:576 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2005 ISBN 92-893-1232-7 This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/publications Nordic Council of Ministers Nordic Council Store Strandstræde 18 Store Strandstræde 18 DK-1255 Copenhagen K DK-1255 Copenhagen K Phone (+45) 3396 0200 Phone (+45) 3396 0400 Fax (+45) 3396 0202 Fax (+45) 3311 1870 www.norden.org Nordic Co-operation in Agriculture and Forestry Agriculture and forestry in the Nordic countries are based on similar natural pre-requisites, and often face common challenges. This has resulted in a long-established tradition of Nordic co-operation in agriculture and forestry. Within the framework of the Plan of Action 1996-2000, the Nordic Council of Ministers (ministers of agriculture and forestry) has given priority to co-operation on quality agricultural production emphazising environmental aspects, the management of genetic resources, the development of regions depending on agriculture and forestry and sustainable forestry. Nordic co-operation Nordic co-operation, one of the oldest and most wide-ranging regional partnerships in the world, involves Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Åland. Co- operation reinforces the sense of Nordic community while respecting national differences and simi- larities, makes it possible to uphold Nordic interests in the world at large and promotes positive relations between neighbouring peoples. -

Ir. D.F. Woudagemaal (D.F. Wouda Steam Pumping Station)

· the original design, the machinery, and the location have remained unchanged since its construction, and WORLD HERITAGE LIST the designed functional structure of the surrounding landscape has undergone no changes or interventions. Wouda Pumping Station (The Netherlands) Category of property No 867 In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in the 1972 World Heritage Convention, this is a group of buildings. History and Description Identification History Centuries of battling against water has created the Nomination Ir. D.F. Woudagemaal (D.F. Dutch landscape. Much of the territory of The Wouda Steam Pumping Netherlands would be flooded if it had not been Station) protected by building dikes over the centuries and kept dry by means of a sophisticated water-control system Location Lemmer, Lemsterland (waterstraat). Continuous efforts to drain lakes and Municipality, Province of open waters in the west of the country began in the Friesland 17th century and continue to the present day. State Party The Netherlands Excess water was initially discharged by means of windmills, which pumped it successively into Date 26 June 1997 intermediate reservoirs and then into open water. This system is admirably represented by the Kinderdijk- Elshout mill network, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1997. The first use of steam for pumping was in 1825 at the Arkelse Dam, near Gorinchem. Radial or centrifugal pumps replaced the water-wheels driven by Justification by State Party windmills. Initially manufactured in England, these The D.F. Wouda Pumping Station consists of a group pumps were being made in The Netherlands by the of combined buildings and structures of outstanding beginning of the 20th century. -

Industrial and Technical Heritage in the World Heritage List

Prepared and edited by UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. Updated by Carole Mongrenier and Francesca Giliberto. Préparé et édité par le Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS. Actualisé par Carole Mongrenier et Francesca Giliberto. Layout and cover : Lucile Smirnov Mise en page et couverture : Lucile Smirnov © UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre, August 2011. ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and sites / Conseil International des Monuments et des Sites 49-51 rue de la Fédération 75015 Paris FRANCE http://www.international.icomos.org UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre / Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS : http://www.international.icomos.org/centre_documentation/index.html Cover photographs: Photos de couverture : Cerro Rico, the mountain that has been mined in Potosi for hundreds of years, looms over the city © Jenny Mealing ; Jantar Mantar © Pablo Nicolás Taibi Cicaré ; The Pumphouse, Liverpool © Mark Mc Kenny Content / Sommaire Australia / Australie .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 2004 - Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens / Palais royal des expositions et jardins Carlton ......................... 2 Austria / Autriche .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1997 - Cultural Landscape of Dachstein/Salzkammergut / Paysage culturel de Hallstatt- Dachstein/Salzkammergut ... -

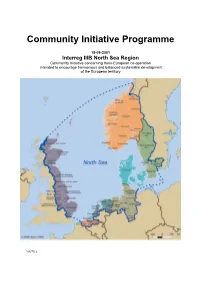

Community Initiative Programme

Community Initiative Programme 18-09-2001 Interreg IIIB North Sea Region Community Initiative concerning trans-European co-operation intended to encourage harmonious and balanced sustainable development of the European territory * NUTS 3 List of Responsible Ministries in Each Country ........................................................................ iii Preface ......................................................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 The Transnational Development Context of the North Sea Region........................................ 1 1.2 Consultation Process ............................................................................................................ 1 1.3 The Use of Indicative Commission Guidance ........................................................................ 4 1.4 Central Aims of the Community Initiative Programme............................................................ 4 1.5 Consistency with Community Policies ................................................................................... 6 1.6 Complementarity with Community Programmes.................................................................... 8 1.7 Key Characteristics of the North Sea Region ........................................................................ 9 1.8 Key Lessons Learnt from Interreg IIC North Sea Programme...............................................