NWIRP Dallas Is an Aerospace Manufacturing Complex Constructed in 1941 As Part of the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download (3

Frontierswww.boeing.com/frontiers JUNEJULY 20092009 // VolumeVolume VIII,VIII, IssueIssue IIIII wingsNew ScanEagle leads Boeing future in unmanned airborne systems market JULY 2009 / BOEING FRONTIERS BOEING FRONTIERS / JULY 2009 / VOLUME VIII, ISSUE III On the Cover 14 Flying into the future Innovative unmanned aircraft systems such as ScanEagle, developed by Boeing subsidiary Insitu, are helping Boeing expand in one of the fastest-growing markets in aerospace. COVER IMAGE: TRAVIS CIELOHA OF INSITU, WITH THE SCANEAGLE UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEM. CDR DOUG KIEM/U.S. NAVY PHOTO: SCANEAGLE IN FLIGHT. CDR DOUG KIEM/U.S. NAVY BOEING FRONTIERS / JULY 2009 / VOLUME VIII, ISSUE III 3 Safer air travel Frontiers Flying today is safer than ever, thanks in large part to the Commercial Publisher: Tom Downey 12 Aviation Safety Team. Working together, representatives from industry, Editorial director: Anne Toulouse government, unions and academia developed and promoted safety initiatives that have improved aviation safety around the globe. EDITORIAL TEAM The team’s efforts recently were recognized with the prestigious Editor: Collier Trophy. Paul Proctor: 312-544-2938 Managing editor (acting): Ann Beach: 312-544-2997 Deputy managing editor: Vineta Plume: 312-544-2954 Out of this world Art director: Brandon Luong: 312-544-2118 For Boeing Mission Control Center employees who design, build and test satellites, the launch is just the beginning. Then comes the critical Commercial Airplanes editor: 24 work of satellite operations. Julie O’Donnell: 206-766-1329 Engineering, Operations & Technology editor: Junu Kim: 312-544-2939 Human Resources and Administration editor: Geoff Potter: 312-544-2946 Apollo 11: A walk to remember Integrated Defense Systems editor: Two Boeing engineers—then a new engineering school graduate and a Diane Stratman: 562-797-1443 28 teenager with lofty aspirations—share the challenges and excitement of Shared Services editor: launching the Apollo 11 mission that put man on the moon 40 years ago Beriah Osorio: 425-577-4157 this summer. -

Download of Your Pictures to Your Computer

w ww om .estesrockets.c TABLE OF CONTENTS Index . .2 Skill Level 2 Rocket Kits . .26 How To Start . .3 Skill Level 3 Rocket Kits . .30 What to Know . .4 “E” Engine Powered Kits . .32 Model Rocket Safety Code . .5 Blurzz™ Rocket Racers . .33 Ready To Fly Starter Sets . .6 How Model Rocket Engines Work . .34 E2X® Starter Sets . .8 Model Rocket Engine Chart . .35 Ready to Fly Launch Sets . .10 Engine Time/Thrust Curves . .36 E2X® Launch Sets . .12 Model Rocket Accessories . .37 Ready To Fly Rockets . .14 Estes Airplanes . .38 E2X® Rocket Kits . .15 Estes Educator™ Products . .41 Skill Level 1 Rocket Kits . .20 Estes Specialty Products . .42 INDEX 220 Swift™. 21 Lucky Seven . 17 36 D Squared™ . 27 Max Trax® Starter Set. 7 Accessories. 37 Mini Super Shot™ Starter Set . 9 AeroX™ Interceptor™R/C Mobile Launcher. 40 Model Rocket Bulk Packs . 41 Air Force 1 Electric R/C Jet. 39 No. 2 Estes Sky Writer® . 17 Air Powered Action Hero. 43 NSA Starship™ . 7 Air Powered Blast Jets®. 43 Operation Search & Destroy™ Launch Set . 11 Air Show™ Launch Set. 13 Oracle™ Digital Camera Rocket . 19 Alpha®. 21 Outlander™ . 31 Alpha III®. 17 Patriot™ Starter Set. 7 Alpha III® Starter Set . 9 Presidential VIP Electric R/C Jet Airplane. 39 Astrocam® 110 . 19 Quickfire™ Catapult R/C Airplane . 39 Baby Bertha™. 21 Quark™ . 21 Bandito™ . 15 Renegade™ . 31 Big Bertha® . 23 Riptide™ Launch Set. 11 Big Daddy™ . 32 Rocket Bulk Packs. 41 Blue Ninja™ . 17 Rubicon . 25 Blurzz™ Rocket Powered Cars . 33 Scissor Wing Transport™ . 31 Bull Pup 12D™. -

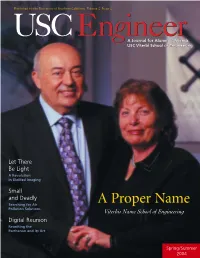

“USC Engineering and I Grew up Together,” Viterbi Likes to Say

Published by the University of Southern California Volume 2 Issue 2 Let There Be Light A Revolution in BioMed Imaging Small and Deadly A Proper Name Searching for Air A Proper Name Pollution Solutions Viterbis Name School of Engineering Digital Reunion Reuniting the Parthenon and its Art Spring/Summer 2004 One man’s algorithm changed the way the world communicates. One couple’s generosity has the potential to do even more. Andrew J. Viterbi: Presenting The University of Southern California’s • Inventor of the Viterbi Algorithm, the basis of Andrew and Erna Viterbi School of Engineering. all of today’s cell phone communications • The co-founder of Qualcomm • Co-developer of CDMA cell phone technology More than 40 years ago, we believed in Andrew Viterbi and granted him a Ph.D. • Member of the National Academy of Engineering, the National Academy of Sciences and the Today, he clearly believes in us. He and his wife of nearly 45 years have offered American Academy of Arts and Sciences • Recipient of the Shannon Award, the Marconi Foundation Award, the Christopher Columbus us their name and the largest naming gift for any school of engineering in the country. With the Award and the IEEE Alexander Graham Bell Medal • USC Engineering Alumnus, Ph.D., 1962 invention of the Viterbi Algorithm, Andrew J. Viterbi made it possible for hundreds of millions of The USC Viterbi School of Engineering: • Ranked #8 in the country (#4 among private cell phone users to communicate simultaneously, without interference. With this generous gift, he universities) by U.S. News & World Report • Faculty includes 23 members of the National further elevates the status of this proud institution, known from this day forward as USC‘s Andrew Academy of Engineering, three winners of the Shannon Award and one co-winner of the 2003 Turing Award and Erna Viterbi School of Engineering. -

The Technologies That Could Prevent More Mysteries Like That of Missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 Page 20

July-August 2014 The technologies that could prevent more mysteries like that of missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 Page 20 Hypersonics after WaveRider p.10 40 tons on a dime at Mars p. 36 A PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF AERONAUTICS AND ASTRONAUTICS AIAA Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics AIAA’s popular book series Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics features books that present a particular, well- defi ned subject refl ecting advances in the fi elds of aerospace science, engineering, and/or technology. POPULAR TITLES Tactical and Strategic Missile Guidance, Sixth Edition Paul Zarchan 1026 pages This best-selling title provides an in-depth look at tactical and strategic missile guidance using common language, notation, and perspective. The sixth edition includes six new chapters on topics related to improving missile guidance system performance and understanding key design concepts and tradeoffs. ISBN: 978-1-60086-894-8 List Price: $134.95 “AIAA Best Seller” AIAA Member Price: $104.95 Morphing Aerospace Vehicles and Structures John Valasek 286 pages Morphing Aerospace Vehicles and Structures is a synthesis of the relevant disciplines and applications involved in the morphing of fi xed wing fl ight vehicles. The book is organized into three major sections: Bio-Inspiration; Control and Dynamics; and Smart Materials and Structures. Most chapters are both tutorial and research-oriented in nature, covering elementary concepts through advanced – and in many cases novel – methodologies. ISBN: 978-1-60086-903-7 “Features the -

Thirty-Five Years in Power for America

R O C K E T D Y Thirty-Five Years in Power for America Rochb,JOH -AL hternaund 4@ocae¢dgne Divis!o n ~PaosRExa; For more Ham a ienemfani, Rockeidync has been ont then, where t/te net iou i s must color(I I I nud intense . As ill,, natim i /ills u « nn°d inl apace, pna°r 1,q Rm 1, 1,1 ync has Dorn a key rlemru f` ,,fill esua"s shny,roilh/' ;fOu/nm/sear idreliabilitu/ urunatcln'd bymnlal/rerrudcrli'ii necumpmutin t/c:maldd. AndOilhI/in( has been thegrnzoth of Rnrketdlpu info a murlel-c/mss loader hr directed enlryy technology, spare-horse puroer sgsteurs and n uc learpmlrr-all a direct rejl eciat I "four pride it l hin" a part of Hie American space, enet'gy and dejolse efforts . Front the rent fires, WI''ii' /ten t/sri' with the best tilenf and oil of the cner ;y roc, nI muslcr, ulillr our ambitions set Otl file must distant stars . Front the uoeninq slur/ 35 years ago, iuc'ire been with the Americml tram drat ta,ardred humankind into space, and in turn, brow ;/lit the 6enl'fits of spare back to Fai lh . Edited by J . Mitchell / Designed by J . Allstott Production by Racketdyne Pub'ications Services Our special appreciatimt to Elm vaurfuez-MOrrtsan of Media 5eroice3 Corporation and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration for their help in securing marry of the photos that appear in this Wok . We are theeprygrateful . The Early Years Thirty-Five Years The Rocketdyne I started working for many years ago was called the Propulsion Center of MACE (Missile and Control Equipment) of North American Aviation . -

Acquisition Story 54 Introduction 2 Who We Were 4 194Os 8 195Os 12

table of contents Introduction 2 Who We Were 4 194Os 8 195Os 12 196Os 18 197Os 26 198Os 30 199Os 34 2OOOs 38 2O1Os 42 Historical Timeline 46 Acquisition Story 54 Who We Are Now 58 Where We Are Going 64 Vision For The Future 68 1 For nearly a century, innovation and reliability have been the hallmarks of two giant U.S. aerospace icons – Aerojet and Rocketdyne. The companies’ propulsion systems have helped to strengthen national defense, launch astronauts into space, and propel unmanned spacecraft to explore the universe. ➢ Aerojet’s diverse rocket propulsion systems have powered military vehicles for decades – from rocket-assisted takeoff for propeller airplanes during World War II – through today’s powerful intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). The systems helped land men on the moon, and maneuvered spacecraft beyond our solar system. ➢ For years, Rocketdyne engines have played a major role in national defense, beginning with powering the United States’ first ICBM to sending modern military communication satellites into orbit. Rocketdyne’s technology also helped launch manned moon missions, propelled space shuttles, and provided the main power system for the International Space Station (ISS). ➢ In 2013, these two rocket propulsion manufacturers became Aerojet Rocketydne, blending expertise and vision to increase efficiency, lower costs, and better compete in the market. Now, as an industry titan, Aerojet Rocketdyne’s talented, passionate employees collaborate to create even greater innovations that protect America and launch its celestial future. 2011 A Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) interceptor is being developed as part of the U.S. Missile Defense Agency’s sea-based Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System. -

Cal Poly Magazine, Spring 2000

EDITOR'S NOTES usic students in the movies had Now, of course, 1984 has come and gone, Mr. Holland and his deferred opus. and 16 years beyond that have passed. I don't M I was blessed with Mr. Higby. know if Mr. Higby is still living. My own On the first day of the semester he entered mother died in 1982, her complicated illness our high school English class cloaked in a teaching me that the future is always black raincoat and wrote his name briskly on ambiguous and it's wise to take it as it comes. the chalkboard. He was dapper and dignified, I learned from Mr. Higby that there is with a closely cropped dark beard. When he truth in any genuinely creative work. As a turned to face us he slipped off his coat and New Century's resolution, I hope once again folded it inside out. The lining was scarlet. to pick up the books that used to serve as Everyone gasped. guides for an uncertain life, and to write my Mr. Higby's coat was a sign that we own fiction. And I hope you will find in this were going to be taken on a series of first Cal Poly Magazine of 2000 some stories wonderful journeys. He was that that will touch your imagination. best of teachers - demanding, fair, In addition to many alumni who are and original. We read The Red Badge supporting the community and the university ofCourage and talked about what war really with their talents and gifts, we are profiling meant. -

Aircraft Designations and Popular Names

Chapter 1 Aircraft Designations and Popular Names Background on the Evolution of Aircraft Designations Aircraft model designation history is very complex. To fully understand the designations, it is important to know the factors that played a role in developing the different missions that aircraft have been called upon to perform. Technological changes affecting aircraft capabilities have resulted in corresponding changes in the operational capabilities and techniques employed by the aircraft. Prior to WWI, the Navy tried various schemes for designating aircraft. In the early period of naval aviation a system was developed to designate an aircraft’s mission. Different aircraft class designations evolved for the various types of missions performed by naval aircraft. This became known as the Aircraft Class Designation System. Numerous changes have been made to this system since the inception of naval aviation in 1911. While reading this section, various references will be made to the Aircraft Class Designation System, Designation of Aircraft, Model Designation of Naval Aircraft, Aircraft Designation System, and Model Designation of Military Aircraft. All of these references refer to the same system involved in designating aircraft classes. This system is then used to develop the specific designations assigned to each type of aircraft operated by the Navy. The F3F-4, TBF-1, AD-3, PBY-5A, A-4, A-6E, and F/A-18C are all examples of specific types of naval aircraft designations, which were developed from the Aircraft Class Designation System. Aircraft Class Designation System Early Period of Naval Aviation up to 1920 The uncertainties during the early period of naval aviation were reflected by the problems encountered in settling on a functional system for designating naval aircraft. -

Boeing History Chronology Boeing Red Barn

Boeing History Chronology Boeing Red Barn PRE-1910 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Boeing History Chronology PRE-1910 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 PRE -1910 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet Museum of Flight Collection HOME PRE-1910 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1881 Oct. 1 William Edward Boeing is born in Detroit, Michigan. 1892 April 6 Donald Wills Douglas is born in Brooklyn, New York. 1895 May 8 James Howard “Dutch” Kindelberger is born in Wheeling, West Virginia. 1898 Oct. 26 Lloyd Carlton Stearman is born in Wellsford, Kansas. 1899 April 9 James Smith McDonnell is born in Denver, Colorado. 1903 Dec. 17 Wilbur and Orville Wright make the first successful powered, manned flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. 1905 Dec. 24 Howard Robard Hughes Jr. is born in Houston, Texas. 1907 Jan. 28 Elrey Borge Jeppesen is born in Lake Charles, Louisiana. HOME PRE-1910 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1910 s Boeing Model 1 B & W seaplane HOME PRE-1910 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1910 January Timber baron William E. Boeing attends the first Los Angeles International Air Meet and develops a passion for aviation. March 10 William Boeing buys yacht customer Edward Heath’s shipyard on the Duwamish River in Seattle. The facility will later become his first airplane factory. 1914 May Donald W. Douglas obtains his Bachelor of Science degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), finishing the four-year course in only two years. -

North American Aviation

North American Aviation North American Aviation Fate merger Successor Rockwell International Founded 1928 Defunct 1996 Location Industry aerospace Parent General Motors Corporation (1933-1948) North American Aviation was a major US aircraft manufacturer. The company was responsible for a number of historic aircraft, including the T-6 Texan trainer, the P-51 Mustang fighter, the B-25 Mitchell bomber, the F-86 Sabre jet fighter, and the X-15 rocket plane, as well as Apollo Command and Service Module, the second stage of the Saturn V rocket, the Space Shuttle orbiter and the B-1 Lancer. Through a series of mergers and sales, North American Aviation is now part of Boeing. History The North American XB-70 Valkyrie Clement Melville Keys founded North American on December 6, 1928, as a holding company that bought and sold interests in various airlines and aviation-relation companies. However, the Air Mail Act of 1934 forced the breakup of such holding companies. The upshot was that North American became a manufacturing company run by James H. "Dutch" Kindelberger (who had been recruited from Douglas Aircraft Company), although it retained Eastern Air Lines until 1938. 1 General Motors Corporation took a controlling interest in NAA and merged it with its General Aviation division in 1933, but retaining the name North American Aviation. Kindelberger moved the company's operations to southern California, which allowed flying year- round, and decided to focus on training aircraft, on the theory that it would be easier than trying to compete with established companies. Its first planes were the GA-15 observation plane and the GA- 16 trainer, followed by the O-47 and BT-9. -

North American Aviation Science Center, 8437 Fallbrook Avenue

-)(a. @F&ooQ-od~~ d --./a 9, f If A..tdkr&R-. From: [email protected] Sent: ~ednesda; December 03,2008 4:41 AM To: FOlA Office Subject: FOlA Request RECEIVED FOIA Request Form DEC 0 1 2008 Fullname: Christine L. Rowe Organization: BY OLS Phone: Fax : Email: Descri or the location of the North American Aviation Science Center, 8437 Fallbro e, Canoga Park, California, 91304. The approximate date of this '3 facility was 1963. All records that have to do with site plans, use of nuclear materials, type of researchAver- d ne b Atomics International or North American Aviation or any other company on this property Approximate site dates would be from the 1950s to present. This would include Bunker Ramo,3 Ramo Wooldridge, Martin Marietta, TRW, Atomics International, N.A.A., North American Aviation Science Center,Hughes, Lockheed, boeing, Rockwell International,Raytheon, and any other company that would have a license to use nuclear materials on this site. Another records search is the location of Atomics International, P.O. Box 309,Canoga Park, California 91304. The purpose of this search is to determine what nuclear materials were used on this site that would cause above Background radiation to appear in monitoring wells onsite and offsite. These records will be given to DTSC and CDPH for review if they reveal any nuclear research that has not been available to them. At this time, the records provided to DTSC start at approximately 1969 although we know that there were facilities before that date. Other addresses at this site could include addresses on (22800 -22951) Roscoe Blvd, or Hughes Aricraft, 8400 Fallbrook Ave, Raytheon Missiles Systems, 8433 Fallbrook Ave, 01,8501, 8511, 8521, 8531 Fallbrook Ave. -

X-Planes: X-1 to X-45, by Jay Miller, Midland Counties Publishing, 2001

AMERICAN X-VEHICLES An Inventory—X-1 to X-50 Centennial of Flight Edition by Dennis R. Jenkins, Tony Landis, and Jay Miller Monographs in Aerospace History No. 31 SP-2003-4531 June 2003 AMERICAN X-VEHICLES An Inventory—X-1 to X-50 Centennial of Flight Edition by Dennis R. Jenkins, Tony Landis, and Jay Miller Monographs in Aerospace History No. 31 SP-2003-4531 June 2003 Suggested Further Reading At the Edge of Space: The X-15 Flight Program, by Milton O. Thompson, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992. Hypersonic: The Story of the North American X-15, by Dennis R. Jenkins and Tony R. Landis, Specialty Press, 2003. The X-Planes: X-1 to X-45, by Jay Miller, Midland Counties Publishing, 2001. Always Another Dawn: The Story of a Rocket Test Pilot, by Scott Crossfield, The World Publishing Company, 1960 (reprinted by Arno Press in 1971 and again by Ayer Company Publishers in 1999). Hypersonics Before the Shuttle: A Concise History of the X-15, by Dennis R. Jenkins, SP-2000-4518, NASA, 2000. Toward Mach 2: The Douglas D-558 Program, edited by J. D. Hunley, SP-4222, NASA, 1999. Flying Without Wings: NASA Lifting Bodies and the Birth of the Space Shuttle, by Milton O. Thompson and Curtis Peebles, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999. Front Cover Photo A group picture of Douglas airplanes, taken for a photographic promotion in 1954 at what is now known as the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, California. The photo includes the X-3 (in front, Air Force serial number 49-2892) then clockwise D-558-I, XF4D-1 (a Navy jet fighter prototype not flown by the NACA), and the first D-558-II (NACA tail number 143, Navy bureau number 37973), which was flown only once by the NACA.