GHQ Air Force Headquarters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 59, Issue 1

Volume 60, Issue 4 Page 1023 Stanford Law Review THE SURPRISINGLY STRONGER CASE FOR THE LEGALITY OF THE NSA SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM: THE FDR PRECEDENT Neal Katyal & Richard Caplan © 2008 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Law Review at 60 STAN. L. REV. 1023 (2008). For information visit http://lawreview.stanford.edu. THE SURPRISINGLY STRONGER CASE FOR THE LEGALITY OF THE NSA SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM: THE FDR PRECEDENT Neal Katyal* and Richard Caplan** INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................1024 I. THE NSA CONTROVERSY .................................................................................1029 A. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act................................................1029 B. The NSA Program .....................................................................................1032 II. THE PRECURSOR TO THE FDR PRECEDENT: NARDONE I AND II........................1035 A. The 1934 Communications Act .................................................................1035 B. FDR’s Thirst for Intelligence ....................................................................1037 C. Nardone I...................................................................................................1041 D. Nardone II .................................................................................................1045 III. FDR’S DEFIANCE OF CONGRESS AND THE SUPREME COURT..........................1047 A. Attorney General -

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II

LESSON 3 Significant Aircraft of World War II ORREST LEE “WOODY” VOSLER of Lyndonville, Quick Write New York, was a radio operator and gunner during F World War ll. He was the second enlisted member of the Army Air Forces to receive the Medal of Honor. Staff Sergeant Vosler was assigned to a bomb group Time and time again we read about heroic acts based in England. On 20 December 1943, fl ying on his accomplished by military fourth combat mission over Bremen, Germany, Vosler’s servicemen and women B-17 was hit by anti-aircraft fi re, severely damaging it during wartime. After reading the story about and forcing it out of formation. Staff Sergeant Vosler, name Vosler was severely wounded in his legs and thighs three things he did to help his crew survive, which by a mortar shell exploding in the radio compartment. earned him the Medal With the tail end of the aircraft destroyed and the tail of Honor. gunner wounded in critical condition, Vosler stepped up and manned the guns. Without a man on the rear guns, the aircraft would have been defenseless against German fi ghters attacking from that direction. Learn About While providing cover fi re from the tail gun, Vosler was • the development of struck in the chest and face. Metal shrapnel was lodged bombers during the war into both of his eyes, impairing his vision. Able only to • the development of see indistinct shapes and blurs, Vosler never left his post fi ghters during the war and continued to fi re. -

Air Force OA-X Light Attack Aircraft/SOCOM Armed Overwatch Program

Updated March 30, 2021 Air Force OA-X Light Attack Aircraft/SOCOM Armed Overwatch Program On October 24, 2019, the U.S. Air Force issued a final OA-X, its ability to operate with coalition partners, and to request for proposals declaring its intent to acquire a new initially evaluate candidate aircraft. The first phase included type of aircraft. The OA-X light attack aircraft is a small, four aircraft: the Sierra Nevada/Embraer A-29; two-seat turboprop airplane designed for operation in Textron/Beechcraft AT-6B; Air Tractor/L3 OA-802 relatively permissive environments. The announcement of a turboprops, variants of which are in service with other formal program followed a series of Air Force countries; and the developmental Textron Scorpion jet. “experiments” to determine the utility of such an aircraft. First-phase operations continued through August 2017. Following conclusion of the Air Force experiments, the program passed to U.S. Special Operations Command as Figure 1. Sierra Nevada/Embraer A-29 the “Armed Overwatch” program, with a goal of acquiring 75 aircraft. Why Light Attack? During 2018, then-Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson often expressed the purpose of a new light attack aircraft as giving the Air Force an ability to free up more sophisticated and expensive assets for other tasks, citing the example of using high-end F-22 jets to destroy a drug laboratory in Afghanistan as an inefficient use of resources. Per-hour operating costs for light attack aircraft are typically about 2%-4% those of advanced fighters. She and other officials have also noted that the 2018 Source: U.S. -

People's Liberation Army Air Force Aviation Training at the Operational

C O R P O R A T I O N From Theory to Practice People’s Liberation Army Air Force Aviation Training at the Operational Unit Lyle J. Morris, Eric Heginbotham For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1415 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9497-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface About the China Aerospace Studies Institute The China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) was created in 2014 at the initiative of the Headquarters, U.S. -

Fm 6-02 Signal Support to Operations

FM 6-02 SIGNAL SUPPORT TO OPERATIONS SEPTEMBER 2019 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes FM 6-02, dated 22 January 2014. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https://armypubs.army.mil/) and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *FM 6-02 Field Manual Headquarters No. 6-02 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 13 September 2019 Signal Support to Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 OVERVIEW OF SIGNAL SUPPORT ........................................................................ 1-1 Section I – The Operational Environment ............................................................. 1-1 Challenges for Army Signal Support ......................................................................... 1-1 Operational Environment Overview ........................................................................... 1-1 Information Environment ........................................................................................... 1-2 Trends ........................................................................................................................ 1-3 Threat Effects on Signal Support ............................................................................. -

2D Stryker Cavalry Regiment

2d Stryker Cavalry Regiment History, Customs and Traditions of the “Second Dragoons” THE OLDEST CONTINUOUSLY SERVING MOUNTED REGIMENT IN THE UNITED STATES ARMY ESTABLISHED 1836 Left Blank Intentionally Dedicated To The soldiers of the 2d Cavalry Regiment who have steadfastly served their nation since 1836. Preface This document is a work of many hands and is intended to be a living reference for the soldiers who serve today as well as a record of the service of those who have preceded them. Special recognition is given to William Heidner and the others who were part of the original team who assembled this book at the direction of the Colonel of the Regiment. In this publication we attempt to preserve and present the essence of what it is to be a 2d Cavalryman. By this effort we wish to carry on the traditions of this special unit and at the same time record the new chapters and pages of history written by today's Dragoons. We intend this to be a living document updated in accordance with the bi-annual schedule of 2d Cavalry Association reunions as well as the experiences and deployments of the Regiment. The content of this document is subject to copyright law and any reproduction or modification of the material here may be subject to approval of the 2d Cavalry Association and the Commanding Officer of the 2d Stryker Cavalry Regiment. All material presented here is based on the best available information at the time of publication and is not intended as a final statement on matters of historical reference nor matters of policy within the Active Regiment. -

CALL for BIDS 00120-1 CALL for BIDS Sealed Bids Will Be Received by the Spokane Airport Board (Owner) at the Spokane Internation

CALL FOR BIDS Sealed bids will be received by the Spokane Airport Board (Owner) at the Spokane International Airport, W. 9000 Airport Drive, Suite 204, Spokane, Washington 99224, until 10:00 a.m., Friday May 29, 2015 for: FELTS FIELD AIRPORT, SPOKANE, WASHINGTON SIA PROJECT #14-07 REHABILITATE TAXIWAYS B, D & E AND TAXILANES AIP 3-53-0073-029/030 It shall be the duty of each Bidder to submit his/her bid on or before the hour and date specified. Any bids received after the time for opening will not be considered. Bids will be publicly opened and read aloud at the designated location and time. A MANDATORY Pre-Bid Conference will be held in the Felts Field Maintenance Building at 11:00 a.m., Friday, May 15, 2015. Enter at Security Gate #1, located on the East 6800 block of Rutter Avenue and follow the signs to the Maintenance Building. Major subcontractors are encouraged to attend; however, it is mandatory for Prime Contractors only. Any bid submitted by a firm, which did not attend this pre-bid conference, will be rejected. The work generally consists of rehabilitation of the full length of Taxiway B, a portion of Taxiway D, Taxiway E and twelve Taxilanes on the airport. Rehabilitation of Taxiway B will include construction of a new holding bay and connecting Taxiway E between Taxiway B and the Runway 4R Threshold. Work items associated with the project include removal of existing asphalt, excavation/embankment, installation of subsurface edge drains, subbase course, base course, asphalt, gravel shoulders, pavement markings, guidance signs, edge lights, stormwater structures, domestic water and sewer, drainage swales, topsoil and seeding. -

SUPER TUCANO Brazilian Air Force (FAB)

DB2 070-A08 Defense and Government Market March 2008 Forward Looking Statement This presentation includes forward-looking statements or statements about events or circumstances which have not occurred. We have based these forward-looking statements largely on our current expectations and projections about future events and financial trends affecting our business and our future financial performance. These forward-looking statements are subject to risks, uncertainties and assumptions, including, among other things: general economic, political and business conditions, both in Brazil and in our market. The words “believes,” “may,” “will,” “estimates,” “continues,” “anticipates,” “intends,” “expects” and similar words are intended to identify forward-looking statements. We undertake no obligations to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements because of new information, future events or other factors. In light of these risks and uncertainties, the forward-looking events and circumstances discussed in this presentation might not occur. Our actual results could differ substantially from those anticipated in our forward-looking statements. DB2 070-A08 INFORMAÇÃO DE PROPRIEDADE DA EMBRAER 2 Business Model Low level of investment, no capital risk Non-recurring investments are paid by first client Very positive cash flow programs It means that Embraer Defense programs have high level of shareholder added value. Besides that the Defense Programs generate technological spin-offs DB2 070-A08 INFORMAÇÃO DE PROPRIEDADE DA EMBRAER 3 Defense Products and Market Segments Intelligence, Surveillance and Training Combat Reconnaissance Transport Systems & Services DB2 070-A08 INFORMAÇÃO DE PROPRIEDADE DA EMBRAER 4 DB2 070-A08 Defense Programs Update Super Tucano FAB SUPER TUCANO Brazilian Air Force (FAB) A-29 (Brazilian Air Force designation) 99 firm orders 58 delivered (44 twin-seater and 14 single-seater)* Four operational bases: Natal (Advanced training), Porto Velho, Boa Vista and Campo Grande AFB (operational squadrons). -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

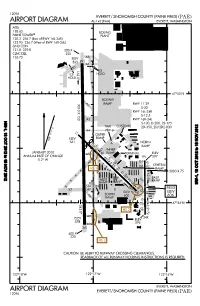

Airport Diagram Airport Diagram

12096 EVERETT/ SNOHOMISH COUNTY (PAINE FIELD) (PAE) AIRPORT DIAGRAM AL-142 (FAA) EVERETT, WASHINGTON ATIS 128.65 BOEING PAINE TOWER PLANT 120.2 256.7 (East of RWY 16L-34R) 132.95 256.7 (West of RWY 16R-34L) GND CON 121.8 339.8 200 X CLNC DEL 220 126.75 AA ELEV 16R 563 A1 K1 162.0^ ILS ILS HOLD HOLD A 47^55'N BOEING 9010 X 150 A2 RAMP RWY 11-29 S-30 RWY 16L-34R S-12.5 A3 RWY 16R-34L NW-1, 18 OCT 2012 to 15 NOV S-100, D-200, 2S-175 TWR CUSTOMS 2D-350, 2D/2D2-830 11 A4 787 B .A OUTER ELEV RAMP VAR 17.1^ E 561 NORTH 117.0^ C RAMP INNER C1 JANUARY 2010 D1 RAMP TERMINAL ELEV A5 16L D-3 ANNUAL RATE OF CHANGE D-3 4514 X 75 C 597 0.2^ W X G1 F1 A6 X D2 CENTRAL X G2 F2 HS 1 RAMP X D3 162.5^ X H D 3000 X 75 A X X X D40.9% UP G3 EAST WEST X X RAMP RAMP W3 X NW-1, 18 OCT 2012 to 15 NOV FIRE F X STATION 297.0^ D5 FIELD K7 A7 E G4 ELEV F4 ELEV A8 SOUTH 29 600 606 RAMP G 342.5^ 47^54'N 342.0^ G5 A G6 HS 2 F6 A9 A 34R ELEV ELEV 578 596 A10 34L 400 X 220 HS 3 CAUTION: BE ALERT TO RUNWAY CROSSING CLEARANCES. READBACK OF ALL RUNWAY HOLDING INSTRUCTIONS IS REQUIRED. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

The German Military and Hitler

RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST The German Military and Hitler Adolf Hitler addresses a rally of the Nazi paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), in 1933. By 1934, the SA had grown to nearly four million members, significantly outnumbering the 100,000 man professional army. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of William O. McWorkman The military played an important role in Germany. It was closely identified with the essence of the nation and operated largely independent of civilian control or politics. With the 1919 Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the victorious powers attempted to undercut the basis for German militarism by imposing restrictions on the German armed forces, including limiting the army to 100,000 men, curtailing the navy, eliminating the air force, and abolishing the military training academies and the General Staff (the elite German military planning institution). On February 3, 1933, four days after being appointed chancellor, Adolf Hitler met with top military leaders to talk candidly about his plans to establish a dictatorship, rebuild the military, reclaim lost territories, and wage war. Although they shared many policy goals (including the cancellation of the Treaty of Versailles, the continued >> RESOURCES ON THE GERMAN MILITARY AND THE HOLOCAUST German Military Leadership and Hitler (continued) expansion of the German armed forces, and the destruction of the perceived communist threat both at home and abroad), many among the military leadership did not fully trust Hitler because of his radicalism and populism. In the following years, however, Hitler gradually established full authority over the military. For example, the 1934 purge of the Nazi Party paramilitary formation, the SA (Sturmabteilung), helped solidify the military’s position in the Third Reich and win the support of its leaders.