Open Thesisfer.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cp Localidad Region 1602 Florida Gba 1603 Villa

CP LOCALIDAD REGION 1602 FLORIDA GBA 1603 VILLA MARTELLI GBA 1604 FLORIDA OESTE GBA 1605 CARAPACHAY / MUNRO GBA 1606 CARAPACHAY GBA 1607 VILLA ADELINA GBA 1608 TRONCOS DEL TALAR GBA 1609 BOULOGNE GBA 1610 RICARDO ROJAS GBA 1611 DON TORCUATO GBA 1612 INGENIERO ADOLFO SOURDEAUX GBA 1613 LOS POLVORINES / P.NOGUES GBA 1614 VILLA DE MAYO GBA 1615 GRAND BOURG GBA 1616 PABLO NOGUES GBA 1617 GRAL.PACHECO / BANCALARI GBA 1618 EL TALAR GBA 1621 BENAVIDEZ GBA 1622 DIQUE LUJAN GBA 1624 RINCÓN DE MILBERG GBA 1636 LA LUCILA / OLIVOS GBA 1637 LA LUCILA GBA 1638 VICENTE LOPEZ GBA 1640 ACASUSSO / MARTINEZ GBA 1641 ACASSUSO GBA 1642 SAN ISIDRO GBA 1643 BECCAR GBA 1644 VICTORIA GBA 1645 VIRREYES GBA 1646 SAN FERNANDO / J.MARMOL GBA 1647 BRAZO LARGO GBA 1648 TIGRE GBA 1650 MIGUELETES / SAN MARTIN GBA 1651 SAN ANDRES / MALAVER GBA 1653 CHILAVERT / V.BALLESTER GBA 1655 JOSE LEON SUAREZ GBA 1657 L.HERMOSA / P.PODESTA GBA 1659 CAMPO DE MAYO GBA 1660 JOSÉ CLEMENTE PAZ GBA 1661 BELLA VISTA GBA 1662 MUÑIZ GBA 1663 SAN MIGUEL GBA 1664 MANUEL ALBERTI GBA 1665 JOSÉ CLEMENTE PAZ GBA 1666 JOSÉ CLEMENTE PAZ GBA 1667 TORTUGUITAS GBA 1669 DEL VISO GBA 1672 VILLA LYNCH GBA 1674 SAENZ PEÑA GBA 1675 VILLA RAFFO GBA 1676 SANTOS LUGARES GBA 1678 CASEROS GBA 1682 VILLA BOSCH / M. CORONADO GBA 1683 MUÑIZ GBA 1684 EL PALOMAR GBA 1685 EL PALOMAR GBA 1686 HURLINGHAN GBA 1687 PABLO PODESTA GBA 1688 VILLA TESEI GBA 1689 REMEDIOS DE ESCALADA GBA 1690 11 DE SEPTIEMBRE GBA 1691 CHURRUCA GBA 1692 EL LIBERTADOR GBA 1702 CIUDADELA / J.INGENIEROS GBA 1703 JOSÉ INGENIEROS GBA 1704 RAMOS MEJIA -

Listado De Farmacias

LISTADO DE FARMACIAS FARMACIA PROVINCIA LOCALIDAD DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO GRAN FARMACIA GALLO AV. CORDOBA 3199 CAPITAL FEDERAL ALMAGRO 4961-4917/4962-5949 DEL MERCADO SPINETTO PICHINCHA 211 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4954-3517 FARMAR I AV. CALLAO 321 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4371-2421 / 4371-4015 RIVADAVIA 2463 AV. RIVADAVIA 2463 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4951-4479/4953-4504 SALUS AV. CORRIENTES 1880 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4371-5405 MANCINI AV. MONTES DE OCA 1229 CAPITAL FEDERAL BARRACAS 4301-1449/4302-5255/5207 DANESA AV. CABILDO 2171 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4787-3100 DANESA SUC. BELGRANO AV.CONGRESO 2486 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4787-3100 FARMAPLUS 24 JURAMENTO 2741 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4782-1679 FARMAPLUS 5 AV. CABILDO 1566 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4783-3941 TKL GALESA AV. CABILDO 1631 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4783-5210 NUEVA SOPER AV. BOEDO 783 CAPITAL FEDERAL BOEDO 4931-1675 SUIZA SAN JUAN AV. BOEDO 937 CAPITAL FEDERAL BOEDO 4931-1458 ACOYTE ACOYTE 435 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4904-0114 FARMAPLUS 18 AV. RIVADAVIA 5014 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4901-0970/2319/2281 FARMAPLUS 19 AV. JOSE MARIA MORENO CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4901-5016/2080 4904-0667 99 FARMAPLUS 7 AV. RIVADAVIA 4718 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4902-9144/4902-8228 OPENFARMA CONTEMPO AV. RIVADAVIA 5444 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4431-4493/4433-1325 TKL NUEVA GONZALEZ AV. RIVADAVIA 5415 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4902-3333 FARMAPLUS 25 25 DE MAYO 222 CAPITAL FEDERAL CENTRO 5275-7000/2094 FARMAPLUS 6 AV. DE MAYO 675 CAPITAL FEDERAL CENTRO 4342-5144/4342-5145 ORIEN SUC. DAFLO AV. DE MAYO 839 CAPITAL FEDERAL CENTRO 4342-5955/5992/5965 SOY ZEUS AV. -

The Dismantling of an Urban School System: Detroit, 1980-2014

The Dismantling of an Urban School System: Detroit, 1980-2014 by Leanne Kang A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Educational Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Jeffrey E. Mirel, Co-Chair Associate Professor Robert B. Bain, Co-Chair Professor Vincent L. Hutchings Associate Professor Vilma M. Mesa Assistant Professor Angeline Spain © Leanne Kang 2015 DEDICATION To my former students. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was possible due in large part to my adviser, Jeffrey Mirel and his seminal study of the Detroit Public Schools (1907-81). Inspired by The Rise and Fall of an Urban School System—which I title my dissertation after—I decided early in my graduate work to investigate what happened to Detroit’s school system after 1980. Thanks to Jeff’s mentorship, I quickly found a research topic that was deeply meaningful and interesting to the very end. He and his wife, Barbara Mirel, are also patrons of my husband’s music. Jeff was the adviser every graduate student hopes to have. The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without Bob Bain courageously jumping into the middle of a project. I was so fortunate; Bob is one of the smartest people I have ever met. He modeled a way of thinking that I will take with me for the rest of my career. His feedback on every draft was incredibly insightful—sometimes groundbreaking— helping me see where to go next in the jungle of data and theory. And always, Bob believed in me and this project. -

The Blind, Intelligence, and Gender in Argentina, 1880-1939

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-25-2016 "Basically Intelligent:" The lindB , Intelligence, and Gender in Argentina, 1880-1939 Rebecca Ann Ellis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Ellis, Rebecca Ann. ""Basically Intelligent:" The lB ind, Intelligence, and Gender in Argentina, 1880-1939." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/27 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rebecca A. Ellis____________________________ Department of History_______________________ This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Elizabeth Hutchison, Chairperson_________________________________________ Dr. Judy Bieber__________________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Jefferson_______________________________________________________ Dr. Jonathan Ablard_______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ -

Grassroots Democracy and Environmental Citizenship in Tigre, Argentina

Grassroots Democracy and Environmental Citizenship in Tigre, Argentina Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Helmus, Andrea Marie Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 08/10/2021 08:16:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/193397 1 GRASSROOTS DEMOCRACY AND ENVIRONMENTAL CITIZENSHIP IN TIGRE, ARGENTINA by Andrea M. Helmus Copyright © Andrea Helmus 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgement of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED: Andrea M. Helmus APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: _________________________________ ___May 7, 2009 ___ William H. Beezley Date Professor of History 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you, Jason, for all of your support and encouragement over the last two years. -

1 Buenos Aires 2018 2 Buenos Aires 2018 3 Concept Et Héritage Jeux Sur Un Terrain Olympique Fertile Qui Donne Des Gains Régionaux Et Des Avantages Mondiaux

Buenos Aires 2018 1 Buenos Aires 2018 2 Buenos Aires 2018 3 Concept et héritage Jeux sur un terrain Olympique fertile qui donne des gains régionaux et des avantages mondiaux Concept and legacy Games on fertile Olympic ground providing regional gains and global benefits Buenos Aires 2018 4 Buenos Aires 2018 5 Thème 1 Theme 1 Concept et héritage Concept and legacy Points clé Highlights celui choisi par 13 millions de Porteños (nom des habitants de season to watch and participate in sport – including many of Des Jeux parfaitement synchronisés en termes de Buenos Aires a cause du port) pour sortir dans la rue et les Games perfectly timed in terms of climate the 50,000 events every year in our parks and other public climat et de popularité parcs afin de profiter de l’arrivée des beaux jours. C’est aussi and popularity spaces. notre saison préférée pour regarder et participer aux activités Des Jeux qui s’appuient sur une tradition olympique sportives - y compris à plusieurs des 50.000 événements qui September is also the optimum month for enjoying the good enflammée Games that build on an ardent Olympic tradition chaque année ont lieu dans nos parcs et nos espaces publics. life for which Buenos Aires has a global reputation. As a result, Des Jeux qui se déroulent dans une capitale Games in a cosmopolitan and youthful world capital those special days offer the best time – and place – to host cosmopolite du Nouveau Monde Septembre est enfin le mois idéal pour sortir dans Buenos the Youth Olympic Games in 2018. -

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz Had Been a Popular Movie, with Richard Dreyfuss Playing a Jewish Nerd

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Photos Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Henry Holt and Company ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on Lenny Kravitz, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For my mother I can’t breathe. Beneath the ground, the wooden casket I am trapped in is being lowered deeper and deeper into the cold, dark earth. Fear overtakes me as I fall into a paralytic state. I can hear the dirt being shoveled over me. My heart pounds through my chest. I can’t scream, and if I could, who would hear me? Just as the final shovel of soil is being packed tightly over me, I convulse out of my nightmare into the sweat- and urine-soaked bed in the small apartment on the island of Manhattan that my family calls home. Shaken and disoriented, I make my way out of the tiny back bedroom into the pitch-dark living room, where my mother and father sleep on a convertible couch. I stand at the foot of their bed just staring … waiting. -

Housing Development: Housing Policy, Slums, and Squatter Settlements in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil and Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1948-1973

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: HOUSING DEVELOPMENT: HOUSING POLICY, SLUMS, AND SQUATTER SETTLEMENTS IN RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL AND BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA, 1948-1973 Leandro Daniel Benmergui, Doctor of Philosophy, 2012 Dissertation directed by: Professor Daryle Williams Department of History University of Maryland This dissertation explores the role of low-income housing in the development of two major Latin American societies that underwent demographic explosion, rural-to- urban migration, and growing urban poverty in the postwar era. The central argument treats popular housing as a constitutive element of urban development, interamerican relations, and citizenship, interrogating the historical processes through which the modern Latin American city became a built environment of contrasts. I argue that local and national governments, social scientists, and technical elites of the postwar Americas sought to modernize Latin American societies by deepening the mechanisms for capitalist accumulation and by creating built environments designed to generate modern sociabilities and behaviors. Elite discourse and policy understood the urban home to be owner-occupied and built with a rationalized domestic layout. The modern home for the poor would rely upon a functioning local government capable of guaranteeing a reliable supply of electricity and clean water, as well as sewage and trash removal. Rational transportation planning would allow the city resident access between the home and workplaces, schools, medical centers, and police posts. As interamerican Cold War relations intensified in response to the Cuban Revolution, policymakers, urban scholars, planners, defined in transnational encounters an acute ―housing problem,‖ a term that condensed the myriad aspects involved in urban dwellings for low-income populations. -

Nombre Direccion Ciudad

NOMBRE DIRECCION CIUDAD 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001EPICENTRAL AV RAMOS MEJIA 1900 CABA 001MUFLUVIALSUD AV PEDRO DE MENDOZA 330 CABA 013COLOADUANADECOLON PEYRET 114 COLON 013MUCOLON PEYRET 114 COLON 018 CARREFOUR ROSARIO CIRC E PRESBIRERO Y CENTR ROSARIO 018 CARREFOUR ROSARIO CIRVUNVALACION Y ALBERTI ROSARIO 02 ALFA MIGUEL CANE 4575 QUILMES 022 CARREFOUR MAR DEL PLA CONSTITUCION Y RUTA 2 MAR DEL PLATA 073MUEZEIZA AU RICCHIERI KM 33 500 SN EZEIZA 12 DE OCTUBRE AV ANDRES BARANDA 1746 QUILMES 135 MARKET LA RIOJA 25 DE MAYO 151 LA RIOJA 135 MARKET LA RIOJA 25 DE MAYO 151 LA RIOJA 1558 SOLUCIONES TECNOLOGI AV ROCA 1558 GRAL ROCA 166LA MATANZA SUR CIRCUNV 2 SECCION GTA SEC CIUDAD EVITA 167 MARKET JUJUY 1 BALCARCE 408 SAN SALVADOR DE JUJUY 18 DE MAYO SRL 25 DE MAYO 660 GRAL ROCA 18 DE MAYO SRL 25 DE MAYO 660 GRAL ROCA 180 CARREFOUR R GRANDE II PERU 76 RIO GRANDE 187 EXP ESCOBAR GELVEZ 530 ESCOBAR 206 MARKET BERUTI BERUTI 2951 CABA 2108 PLAZA OESTE PARKING J M DE ROSAS 658 MORON 2108 PLAZA OESTE PARKING J M DE ROSAS 658 MORON 219 CARREFOUR CABALLITO DONATO ALVAREZ 1351 CABA 21948421 URQUIZA 762 SALTA 21956545 PJE ESCUADRON DE LOS GAU SALTA 21961143 MITRE 399 SALTA 21965217 HIPOLITO YRIGOYEN 737 SALTA 21968433 URQUIZA 867 SALTA 220 ELECTRICIDAD ENTRE RIOS 397 ESQ BELGR TICINO 22111744 ESPANA 1033 SALTA 22113310 LEGUIZAMON 470 SALTA 22116355 CALLE DE LOS RIOS 0 SALTA 22129878 SAN MARTIN 420 JESUS MARIA 22135806 LORENZO BARCALA 672 CORDOBA 22135940 AV RICHIERI -

Offering Memorandum

OFFERING MEMORANDUM The Province of Buenos Aires (A Province of Argentina) USD 750,000,000 10.875% Notes Due 2021 The Province will pay interest on the Notes on January 26 and July 26 of each year, beginning July 26, 2011. The Notes will mature on January 26, 2021. The Province will pay the principal of the Notes in three installments: 33.33% on January 26, 2019, 33.33% on January 26, 2020 and 33.34% on January 26, 2021. The Notes will be direct, unconditional, unsecured and unsubordinated obligations of the Province, ranking pari passu, without any preference, among themselves and with all other present and future unsecured and unsubordinated indebtedness from time to time outstanding of the Province, except as otherwise provided by law. Application will be made to list the Notes on the Luxembourg Stock Exchange, and to have the Notes admitted to trading on the Euro MTF market of the Luxembourg Stock Exchange, and the Province will apply to list the Notes on the Buenos Aires Stock Exchange and the Argentine Mercado Abierto Electrónico. Investing in the Notes involves risks that are described in the “Risk Factors” section beginning on page 10 of this offering memorandum. Price to investors: 97.916%, plus accrued interest, if any, from January 26, 2011. The Notes have not been, and will not be, registered under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended, or the securities laws of any other jurisdiction. Unless they are registered, the Notes may be offered only in transactions that are exempt from registration under the Securities Act or the securities law of any other jurisdiction. -

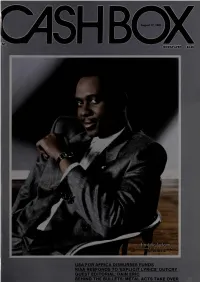

Cash Box Introduced the Unique Weekly Feature

MB USA FOR AFRICA DISBURSES FUNDS RIAA RESPONDS TO EXPLICIT LYRICS’ OUTCRY GUEST EDITORIAL: PAIN ERIC BEHIND THE BULLETS: METAL ACTS TAKE OVER new laces to n September 10, 1977, Cash Box introduced the unique weekly feature. New Faces To Watch. Debuting acts are universally considered the life blood of the recording industry, and over the last seven years Cash Box has been first to spotlight new and developing artists, many of whom have gone on to chart topping successes. Having chronicled the development of new talent these seven years, it gives us great pleasure to celebrate their success with our seventh annual New Faces To Watch Supplement. We will again honor those artists who have rewarded the faith, energy, committment and vision of their labels this past year. The supplemenfs layout will be in easy reference pull-out form, making it a year-round historical gudie for the industry. It will contain select, original profiles as well as an updated summary including chart histories, gold and platinum achievements, grammy awards, and revised up-to-date biographies. We know you will want to participate in this tribute, showing both where we have been and where we are going as an industry. The New Faces To Watch Supplement will be included in the August 31st issue of Cash Box, on sale August The advertising deadline is August 22nd. Reserve Advertising Space Now! NEW YORK LOS ANGELES NASHVILLE J.B. CARMICLE SPENCE BERLAND JOHN LENTZ 212-586-2640 213-464-8241 615-244-2898 9 C4SH r BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT -

307 – Septiembre 2020

Septiembre 2020 • Año 28 • Nº 307 • Encuentro Delta Página 4 • Historias: Barrios de Vicente López Página 6 • A la primavera Página 12 • Una muchacha ojos color del glaciar Página 14 • Saliendo Página 17 • Patología de la construcción Página 24 • Servicios en general Jesús en el Huerto de los Olivos. Patrono del Partido de Vte. López • Actividades gratuitas Rosetti Cristales - Corte y Colocación © ASESORAMIENTO - C ALIDAD Y EFICACIA Refrigeración “TEM ” Vidrios Espejos Mamparas Mosquiteros Instalación y Reparación y Cerramientos de aluminio de Split frío/calor Aires Acondicionados Centrales Urgencias 15-4940-9057 Reparación de Heladeras familiares Rosetti 2516 (Olivos) 4797-0092 y comerciales [email protected] Instagram y Facebook: @rosetti cristales 15-2458-7948 Presupuesto sin cargo A CDON TERATLAMIGENTOA MÉDCICO E Inhibidores del apetito no anfetamínicos - Quemadores de grasas - Lipolíticos Aristóbulo del Valle 1535. Puente Saavedra. Informes : 15-6532-1642 ● Martes de 18 a 20 hs. Concurrir sin Turno Enfermería A Domicilio FUMIGRAN - Higiene y confort CONTROL DE PLAGAS - Inyecciones Habilitación C.A.B.A. Nº 868436 - Prov. Bs. As. Nº 5191 - Toma de presión arterial No afecta a animales Cotización TRASLADO DE PACIENTES de sangre caliente ni SIN CARGO al Ser Humano. con trastornos de locomoción para diversos trámites INOCUO LEXIBILIDAD F Tef.: 11-2450 7288 - Zona Norte Personas animales Certificación con pueden presenciar Oblea expedida por nuestra labor. Ente Regulador EL OUTLET DE LOS RETAZOS SIN OLOR CERTIFICADO Calle Carlos