Where Is the Bubble: Atypical and Unusual Thoracic Air D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomical Overview

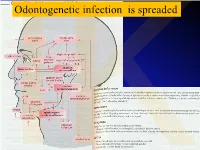

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

MSS 1. a Patient Presented to a Traumatologist with a Trauma Of

MSS 1. A patient presented to a traumatologist with a trauma of shoulder. What wall of axillary cavity contains foramen trilaterum and foramen quadrilaterum? a) anterior b) posterior c) lateral d) medial e) intermediate 2. A patient presented to a traumatologist with a trauma of leg, which he had sustained at a sport competition. Upon examination, damage of posterior muscle, that is attached to calcaneus by its tendon, was found. This muscle is: a) triceps surae b) tibialis posterior c) popliteus d) fibularis longus e) fibularis brevis 3. In the course of a cesarean section, an incision was made in the pubic area and vagina of rectus abdominis muscle was cut. What does anterior wall of the vagina of rectus abdominis muscle consist of? A. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus internus abdominis. B. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. pyramidalis. C. aponeurosis of m. obliquus internus abdominis, m. obliquus externus abdominis. D. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus externus abdominis. E. aponeurosis of m. transversus abdominis, m. obliquus internus abdominis 4. A 30 year-old woman complained of pain in the lower part of her forearm. Traumatologist found that her radio-carpal joint was damaged. This joint is: A. complex, ellipsoid B.simple, ellipsoid C.complex, cylindrical D.simple, cylindrical E.complex condylar 5. A woman was brought by an ambulance to the emergency department with a trauma of the cervical part of her vertebral column. Radiologist diagnosed a fracture of a nonbifid spinous processes of one of her cervical vertebrae. Spinous process of what cervical vertebra is fractured? A.VI. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0

Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University 0 Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University SPLANCHNOLOGY, CARDIOVASCULAR AND IMMUNE SYSTEMS STUDY GUIDE Recommended by the Academic Council of Sumy State University Sumy Sumy State University 2016 1 УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 С72 Composite authors: V. I. Bumeister, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor; L. G. Sulim, Senior Lecturer; O. O. Prykhodko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant; O. S. Yarmolenko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant Reviewers: I. L. Kolisnyk – Associate Professor Ph. D., Kharkiv National Medical University; M. V. Pogorelov – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Sumy State University Recommended for publication by Academic Council of Sumy State University as а study guide (minutes № 5 of 10.11.2016) Splanchnology Cardiovascular and Immune Systems : study guide / С72 V. I. Bumeister, L. G. Sulim, O. O. Prykhodko, O. S. Yarmolenko. – Sumy : Sumy State University, 2016. – 253 p. This manual is intended for the students of medical higher educational institutions of IV accreditation level who study Human Anatomy in the English language. Посібник рекомендований для студентів вищих медичних навчальних закладів IV рівня акредитації, які вивчають анатомію людини англійською мовою. УДК 611.1/.6+612.1+612.017.1](072) ББК 28.863.5я73 © Bumeister V. I., Sulim L G., Prykhodko О. O., Yarmolenko O. S., 2016 © Sumy State University, 2016 2 Hippocratic Oath «Ὄμνυμι Ἀπόλλωνα ἰητρὸν, καὶ Ἀσκληπιὸν, καὶ Ὑγείαν, καὶ Πανάκειαν, καὶ θεοὺς πάντας τε καὶ πάσας, ἵστορας ποιεύμενος, ἐπιτελέα ποιήσειν κατὰ δύναμιν καὶ κρίσιν ἐμὴν ὅρκον τόνδε καὶ ξυγγραφὴν τήνδε. -

TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 Thru 49999 Page Updated: January 2021

tar and non cd4 1 TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 Page updated: January 2021 Surgery Digestive System Note: Refer to the TAR and Non-Benefit: Introduction to List in this manual for more information about the categories of benefit restrictions. Lips Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40490 Biopsy of lip Assistant Surgeon services not payable Other Procedures Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40799 Unlisted procedure, lips Requires TAR, Primary Surgeon/ Provider Vestibule of Mouth Incision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40800 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40801 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, complicated Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40804 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40805 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, Assistant Surgeon complicated services not payable 40806 Incision labial frenum Non-Benefit Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40808 Biopsy, vestibule of mouth Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40810 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, without Non-Benefit repair Part 2 – TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 tar and non cd4 2 Page updated: January 2021 Excision (continued) Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40812 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon repair services not payable 40816 Excision of lesion, mouth, mucosa/submucosa, Assistant Surgeon complex services not payable 40819 Excision of frenum, labial -

Deep Neck Space Infection

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 DEEP NECK SPACE INFECTION- A CLINICAL INSIGHT Correspondance to:Dr.Vijay Ebenezer 1, Professor Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. Email id: [email protected], Contact no: 9840136328 Names of the author(s): 1)Dr. Vijay Ebenezer1 ,Professor and Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree Balaji dental college and hospital , BIHER, Chennai-600100, Tamilnadu , India. 2)Dr. Balakrishnan Ramalingam2, professor in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. INTRODUCTION Deep neck infections are a life threatening condition but can be treated, the infections affects the deep cervical space and is characterized by rapid progression. These infections remains as a serious health problem with significant morbidity and potential mortality. These infections most frequently has its origin from the local extension of infections from tonsils, parotid glands, cervical lymph nodes, and odontogenic structures. Classically it presents with symptoms related to local pressure effects on the respiratory, nervous, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract (particularly neck mass/swelling/induration, dysphagia, dysphonia, and trismus). The specific presenting symptoms will be related to the deep neck space involved (parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, prevertebral, submental, masticator, etc).1,2,3,4,5 ETIOLOGY Deep neck space infections are polymicrobial, with their source of origin from the normal flora of the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. The most common deep neck infections among adults arise from dental and periodontal structures, with the second most common source being from the tonsils. -

Neck Formation and Growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS in NECK

Neck formation and growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS IN NECK. ANATOMICAL BACKGROUND FOR URGENT LIFE SAVING PERFORMANCES. orofac Ivo Klepáček orofac Vymezení oblasti krku Extent of the neck region Sensitivní oblasti V1, V2, V3., plexus cervicalis orofac * * * * * orofac** * orofac orofac orofaccranial middle caudal orofac orofac Clinical classification of neck lymph nodes orofacClinical classification of neck lymphatic nodes: I - VI Nodi lymphatici out of regiones above: Perifacial, periparotic, retroauricular, suboccipital, retropharyngeal Metastasa v krčních uzlinách Metastasis in cervical orofaclymphonodi TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS orofacand SPACES Regio colli anterior anterior neck triangle Trigonae : submentale, submandibulare, caroticum (musculare), regio suprasternalis Triangles : submental, submandibular, carotic (muscular), orofacsuprasternal region podkožní sval na povrchové krční fascii r. colli nervi facialis ovládá napětí kůže krku Platysma orofac proc. mastoideus manubrium sterni, clavicula Sternocleidomastoid m. n.accessorius (XI) + branches sternocleidomastoideus from plexus cervicalis orofac Punctum nervosum (Erb ´s point) : there C5 and C6 nerves are connected, + branches from suprascapulari and subclavian nerves orofacWilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840 - 1921), German neurologist orofac orofac mm. suprahyoid suprahyoidei and et mm. infrahyoid orofacinfrahyoidei muscles orofac Thyroid gland and vascular + nerve bundle in neck orofac orofac Žíly veins orofac štítná žláza příštitné orofactělísko a. thyroidea inferior n. laryngeus inferior -

Clinical Anatomy of the Neck Region

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OF THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA STATE UNIVERSITY OF MEDICINE AND PHARMACY "NICOLAE TESTEMIȚANU" DEPARTMENT TOPOGRAPHIC ANATOMY AND OPERATIVE SURGERY Gheorghe GUZUN, Radu TURCHIN, Boris TOPOR, Serghei SUMAN CLINICAL ANATOMY OF THE NECK REGION Methodical recommendations for students CHISINAU, 2017 CZU 611.93(076.5) C 57 Lucrarea a fost aprobată de Consiliul Metodic Central al USMF “Nicolae Testemițanu”; proces-verbal nr. 2 din 10.03.2017 Autori: Gheorghe GUZUN – dr. med, conf. univ. Radu TURCHIN – dr.șt.med., conf. univ. Boris TOPOR – dr.hab.șt.med., prof. univ. Serghei SUMAN – dr.hab.șt.med., conf. univ. Recenzenți: Ilia catereniuc – dr.hab.șt.med., prof. univ. Nicolae Fruntașu – dr.hab.șt.med., prof. univ. Machetare: Serghei Suman – dr.hab.șt.med., conf. univ. DESCRIEREA CIP A CAMEREI NAȚIONALE A CĂRȚII Clinical anatomy of the neck region : Methodical recommendations for students / Gheorghe Guzun, Radu Turchin, Boris Topor [et al.] ; State Univ. of Medicine and Pharmacy "Nicolae Testemiţanu", Dep. Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery. – Chişinău : S. n., 2017 (Tipogr. "Print-Caro"). – 52 p. : fig. 100 ex. ISBN 978-9975-56-466-3. 611.93(076.5) C 57 ISBN 978-9975-56-466-3. CEP Medicina, 2017 Gheorghe Guzun, Radu Turchin, Viorel Nacu, Boris Topor, 2017. © Gheorghe Guzun, 2017 CLINICAL ANATOMY OF THE NECK The upper limit of the neck (cefalocervical limit) is a conventional line that crosses the lower jaw (basis of mandible) and its angle, the bottom of the external auditory canal, the apex of mastoid process (procesuus mastoideus) and superior nuchal line (linea nuchae superior) to the external occipital protuberance (occipitalis external protuberance). -

Deep Neck Space Infectionsdeep Neck Space Infections

Deep Neck Space InfectionsDeep Neck Space Infections Disclaimer: The pictures used in this presentation and its content has been obtained from a number of sources. Their use is purely for academic and teaching purposes. The contents of this presentation do not have any intended commercial use. In case the owner of any of the pictures has any objection and seeks their removal please contact at [email protected] . These pictures will be removed immediately. The fibrous connective tissue that constitutes the cervical fascia varies from loose areolar tissue to dense fibrous bands. This fascia serves to envelope the muscles, nerves, vessels and viscera of the neck, thereby forming planes and potential spaces that serve to divide the neck into functional units. It functions to both direct and limit the spread of disease processes in the neck. The cervical fascia can be divided into a simpler superficial layer and a more complex deep layer that is further subdivided into superficial, middle and deep layers. The superficial layer of cervical fascia ensheaths the platysma in the neck and extends superiorly in the face to cover the mimetic muscles. It is the equivalent of subcutaneous tissue elsewhere in the body and forms a continuous sheet from the head and neck to the chest, shoulders and axilla. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia is also known as the investing layer. It follows the “rule of twos”—it envelops two muscles, two glands and forms two spaces. It originates from the spinous processes of the vertebral column and spreads circumferentially around the neck. -

Fascia and Spaces on the Neck: Myths and Reality Fascije I Prostori Vrata: Mit I Stvarnost

Review/Pregledni članak Fascia and spaces on the neck: myths and reality Fascije i prostori vrata: mit i stvarnost Georg Feigl* Institute of Anatomy, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria Abstract. The ongoing discussion concerning the interpretation of existing or not existing fas- ciae on the neck needs a clarification and a valid terminology. Based on the dissection experi- ence of the last four decades and therefore of about 1000 cadavers, we investigated the fas- cias and spaces on the neck and compared it to the existing internationally used terminology and interpretations of textbooks and publications. All findings were documented by photog- raphy and the dissections performed on cadavers embalmed with Thiel´s method. Neglected fascias, such as the intercarotid fascia located between both carotid sheaths and passing be- hind the visceras or the Fascia cervicalis media as a fascia between the two omohyoid mus- cles, were dissected on each cadaver. The ”Danger space” therefore was limited by fibrous walls on four sides at level of the carotid triangle. Ventrally there was the intercarotid fascia, laterally the alar fascia, and dorsally the prevertebral fascia. The intercarotid fascia is a clear fibrous wall between the Danger Space and the ventrally located retropharyngeal space. Lat- ter space has a continuation to the pretracheal space which is ventrally limited by the middle cervical fascia. The existence of an intercarotid fascia is crucial for a correct interpretation of any bleeding or inflammation processes, because it changes the topography of the existing spaces such as the retropharyngeal or “Danger space” as well. As a consequence, the existing terminology should be discussed and needs to be adapted. -

Suprahyoid and Infrahyoid Neck Overview

Suprahyoid and Infrahyoid Neck Overview Imaging Approaches & Indications by space, the skull base interactions above and IHN extension below are apparent. Neither CT nor MR is a perfect modality for imaging the • PPS has bland triangular skull base abutment without extracranial H&N. MR is most useful in the suprahyoid neck critical foramen involved; it empties inferiorly into (SHN) because it is less affected by oral cavity dental amalgam submandibular space (SMS) artifact. The SHN tissue is less affected by motion compared • PMS touches posterior basisphenoid and anterior with the infrahyoid neck (IHN); therefore, the MR image basiocciput, including foramen lacerum; PMS includes quality is not degraded by movement seen in the IHN. Axial nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and hypopharyngeal and coronal T1 fat-saturated enhanced MR is superior to CECT mucosal surfaces in defining soft tissue extent of tumor, perineural tumor • MS superior skull base interaction includes zygomatic spread, and dural/intracranial spread. When MR is combined with CT of the facial bones and skull base, a clinician can obtain arch, condylar fossa, skull base, including foramen ovale (CNV3), and foramen spinosum (middle meningeal precise mapping of SHN lesions. Suprahyoid and Infrahyoid Neck artery); MS ends at inferior surface of body of mandible CECT is the modality of choice when IHN and mediastinum are • PS abuts floor of external auditory canal, mastoid tip, imaged. Swallowing, coughing, and breathing makes this area including stylomastoid foramen (CNVII); parotid tail a "moving target" for the imager. MR image quality is often extends inferiorly into posterior SMS degraded as a result. Multislice CT with multiplanar • CS meets jugular foramen (CNIX-XI) floor, hypoglossal reformations now permits exquisite images of the IHN canal (CNXII), and petrous internal carotid artery canal; unaffected by movement. -

Complex Odontogenic Infections

Complex Odontogenic Infections Larry ). Peterson CHAPTEROUTLINE FASCIAL SPACE INFECTIONS Maxillary Spaces MANDIBULAR SPACES Secondary Fascial Spaces Cervical Fascial Spaces Management of Fascial Space Infections dontogenic infections are usually mild and easily and causes infection in the adjacent tissue. Whether or treated by antibiotic administration and local sur- not this becomes a vestibular or fascial space abscess is 0 gical treatment. Abscess formation in the bucco- determined primarily by the relationship of the muscle lingual vestibule is managed by simple intraoral incision attachment to the point at which the infection perfo- and drainage (I&D) procedures, occasionally including rates. Most odontogenic infections penetrate the bone dental extraction. (The principles of management of rou- in such a way that they become vestibular abscesses. tine odontogenic infections are discussed in Chapter 15.) On occasion they erode into fascial spaces directly, Some odontogenic infections are very serious and require which causes a fascial space infection (Fig. 16-1). Fascial management by clinicians who have extensive training spaces are fascia-lined areas that can be eroded or dis- and experience. Even after the advent of antibiotics and tended by purulent exudate. These areas are potential improved dental health, serious odontogenic infections spaces that do not exist in healthy people but become still sometimes result in death. These deaths occur when filled during infections. Some contain named neurovas- the infection reaches areas distant from the alveolar cular structures and are known as coinpnrtments; others, process. The purpose of this chapter is to present which are filled with loose areolar connective tissue, are overviews of fascial space infections of the head and neck known as clefts.