The Classical Theory of Imitation in the Works of Horace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17Th-First Half of the 18Th Century

The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Siedina, Giovanna. 2014. The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13065007 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2014 Giovanna Siedina All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Author: Professor George G. Grabowicz Giovanna Siedina The Reception of Horace in the Courses of Poetics at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy: 17th-First Half of the 18th Century Abstract For the first time, the reception of the poetic legacy of the Latin poet Horace (65 B.C.-8 B.C.) in the poetics courses taught at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy (17th-first half of the 18th century) has become the subject of a wide-ranging research project presented in this dissertation. Quotations from Horace and references to his oeuvre have been divided according to the function they perform in the poetics manuals, the aim of which was to teach pupils how to compose Latin poetry. Three main aspects have been identified: the first consists of theoretical recommendations useful to the would-be poets, which are taken mainly from Horace’s Ars poetica. -

Herodotus' Reputation in Latin Literature from Cicero to the 12Th

CHAPTER 9 Herodotus’ Reputation in Latin Literature from Cicero to the 12th Century Félix Racine Introduction Herodotean scholarship has paid little attention to the reception of the Histories in the Latin West before the Renaissance. Arnaldo Momigliano’s sem- inal article “The Place of Herodotus in the History of Historiography”, to take a celebrated example, considers in turn ancient Greek views on Herodotus and those of Renaissance scholars, but has little to say on Latin opinions save those of Cicero.1 And why should it not be so? Few Western readers of Herodotus are known from the Imperial era, and virtually none from the Middle Ages. A closer look at the evidence reveals a more nuanced picture of the vicis- situdes of Herodotus’ name in the West, and of stories originally found in his Histories. Let us consider the 12th-century French scholar Peter Comestor (“The Voracious”, so named from the many books he avidly read), who wrote an exegetical and historical commentary on the Scriptures, the Historia Scholastica. Comestor’s source material was broad indeed—it included classi- cal and Christian authors (in Latin; he knew very little Greek) and his historical horizon embraced not only Sacred history but also classical Rome, Greece and Persia. Inserted between a discussion of the Book of Habakkuk and the end of the Babylonian Captivity is an account of Cyrus’ life focusing on his birth and childhood, much altered since its first telling by Herodotus. The story came to Peter Comestor through Pompeius Trogus’ Philippic History, abridged by Justin in the 4th century (Just. -

Political Dissent in Groves, Caves, and Grottos Nina Bhatia, Washington University in St

POLITICAL DISSENT IN GROVES, CAVES, AND GROTTOS NINA BHATIA, WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS In Ode 3.25 Horace invokes Bacchus for divine inspiration while he is composing a poem that will honor the living deification of Augustus. As such, this poem is typically viewed as pro-Augustan propaganda. However, contextualization of Horace’s Odes demonstrates their multifaceted nature revealing small rebellions against Augustus. The goal of this project is to demonstrate the underlying subversive nature of Ode 3.25 through contextualization by examining Antony’s link to Bacchus, the invocation of Bacchus for poetic inspiration, and the contemporary perceptions of deification. Patron Gods and Political Propaganda Invocation Deification Antony created a divine lineage for himself from Bacchus Ode 3.25’s first stanza does more than just recall the Bacchic trope of The most contemporarily recent, posthumous deification was going so far as to “look like him in both physical appearance and possession. Horace’s use of nemora, specus, and antriis immediately pulls readers into that of Julius Caesar. The arrival of a comet, often termed the sidus Iulium, clothing” (Freyburger-Garland 24). This Bacchic branding was the wild, Bacchic setting. That is then immediately countered by the following: during the funerary games held for Caesar was celebrated as evidence for amplified by Antony’s time ruling in Egypt where he was deified as Julius Caesar’s entrance to consilium Iovis. The sidus Iulium imagery was often quibus antris egregii Caesaris audiar In which cave shall I be heard the syncretic Dionysus-Osiris. This is demonstrated by the arrival aeternum meditans decus musing to induct distinguished used to legitimize Augustus’s claim to power. -

Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Classical Studies Faculty Publications Classical Studies 2016 Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/classicalstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Damer, Erika Zimmermann. "Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12." Helios 43, no. 1 (2016): 55-85. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 ERIKA ZIMMERMANN DAMER When in Book 1 of his Epistles Horace reflects back upon the beginning of his career in lyric poetry, he celebrates his adaptation of Archilochean iambos to the Latin language. He further states that while he followed the meter and spirit of Archilochus, his own iambi did not follow the matter and attacking words that drove the daughters of Lycambes to commit suicide (Epist. 1.19.23–5, 31).1 The paired erotic invectives, Epodes 8 and 12, however, thematize the poet’s sexual impotence and his disgust dur- ing encounters with a repulsive sexual partner. The tone of these Epodes is unmistakably that of harsh invective, and the virulent targeting of the mulieres’ revolting bodies is precisely in line with an Archilochean poetics that uses sexually-explicit, graphic obscenities as well as animal compari- sons for the sake of a poetic attack. -

Cas Cl 230: the Golden Age of Latin Literature

CAS CL 230: THE GOLDEN AGE OF LATIN LITERATURE In Workflow 1. CASCL Chair ([email protected]; [email protected]) 2. CAS Dean ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; jessmroh; lcherch; [email protected]; [email protected]) 3. GEC SubCommittees ([email protected]) 4. University Gen Ed Committee Chair ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) 5. Final Approval ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) Approval Path 1. Mon, 30 Oct 2017 14:00:40 GMT MEGHAN ELIZABETH KELLY (mekel): Approved for CASCL Chair New Proposal Date Submitted: Mon, 30 Oct 2017 12:21:14 GMT Viewing: The Golden Age of Latin Literature Last edit: Mon, 30 Oct 2017 12:21:14 GMT Changes proposed by: mekel Section One – Provenance of Proposal Proposer Information Name Title Email School/College Department Name Leah Kronenberg Assoc. Prof. [email protected] CAS Classical Studies Section Two – Course or Co-Curricular Activity Identifiers What are you proposing? Course College College of Arts & Sciences Department CLASSICAL STUDIES Subject Code CAS CL - Classical Studies Course Number 230 Course/Co-curricular Title The Golden Age of Latin Literature Short Title Gold Latin Lit This is: A New Course Did you participate in a CTL workshop for the development of this activity? No Bulletin (40-word) Course Description An in-depth exploration in English of some of the greatest poets from Ancient Rome, including Catullus, Virgil, and Ovid. Examines the Romans' engagement with Greek literature and the development of their own "Classics," from personal love poetry to profound epic. Prerequisites, -

Some Problems in Prosody

1903·] Some Problems in Prosody. 33 ARTICLE III. SOME PROBLEMS IN PROSODY. BY PI10PlCSSOI1 R.aBUT W. KAGOUN, PR.D. IT has been shown repeatedly, in the scientific world, that theory must be supplemented by practice. In some cases, indeed, practice has succeeded in obtaining satisfac tory results after theory has failed. Deposits of Urate of Soda in the joints, caused by an excess of Uric acid in the blood, were long held to be practically insoluble, although Carbonate of Lithia was supposed to have a solvent effect upon them. The use of Tetra·Ethyl-Ammonium Hydrox ide as a medicine, to dissolve these deposits and remove the gout and rheumatism which they cause, is said to be due to some experiments made by Edison because a friend of his had the gout. Mter scientific men had decided that electric lighting could never be made sufficiently cheap to be practicable, he discovered the incandescent lamp, by continuing his experiments in spite of their ridicule.1 Two young men who "would not accept the dictum of the authorities that phosphorus ... cannot be expelled from iron ores at a high temperature, ... set to work ... to see whether the scientific world had not blundered.'" To drive the phosphorus out of low-grade ores and convert them into Bessemer steel, required a "pot-lining" capable of enduring 25000 F. The quest seemed extraordinary, to say the least; nevertheless the task was accomplished. This appears to justify the remark that "Thomas is our modem Moses";8 but, striking as the figure is, the young ICf. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 17 February 2016 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Petrovic, Ivana (2006) 'Delusions of grandeur : Homer, Zeus and the Telchines in Callimachus Reply (Aitia Fr. 1) and Iambus 6.', Antike und Abendland., 52 . pp. 16-41. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/anti.2006.52.issue- 1/9783110186345.16/9783110186345.16.xml?format=INT Publisher's copyright statement: The nal publication is available at www.degruyter.com Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk L IJ lVANA PETROVIC Delusions of Grandeur: Homer, Zeus and the Telchines in Callimachus' Reply (Aitia Fr. 1) and Iambus 6'' The visual representations of Homer were often modelled upon those of Zeus. Fur thermore, not only in the visual arts, but in poetry as well Homer was often in one way or another brought in connection with Zeus. -

Sampling Real Life: Creative Appropriation in Public Spaces

Sampling Real Life: Creative Appropriation in Public Spaces Elsa M. Lankford Electronic Media & Film (EMF) Towson University [email protected] I. Introduction Enter an art museum or a library and you will find numerous examples of appropriation, all or most of which were most likely legal at the time. From the birth of copyright and the idea that an author, encompassed as a writer, artist, composer, or musician, is the creator of a completely original work, our legal and moral perceptions of appropriation have changed. Merriam-Webster defines appropriation in multiple ways, two of which apply to the discussion of art and appropriation. The first, “to take exclusive possession of” and the second “to take or make use of without authority or right.”1 The battle over rights and appropriation is not one that is only fought in the courtroom and gallery, it also concerns our own lives. Many aspects of our lives involve appropriation, from pagan holidays appropriated into the Christian calendar to the music we listen to, even to the words we speak or write appropriated from other countries and cultures. As artists, appropriation in many forms makes its way into works of any media. The topic of appropriation leads to a discussion of where our creative ideas come from. They, in some sense, have been appropriated as well. Whether we overhear a snippet of a conversation that ends up woven into a creative work or we take a picture of somebody, unknowingly, as they walk down a tree-shadowed street, we are appropriating life. For centuries, artists have been inspired by public life, and the stories and images of others have been appropriated into their work. -

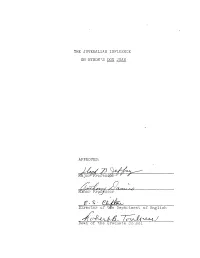

The Juvenalian Influence on Byronts Don Juan Approved

THE JUVENALIAN INFLUENCE ON BYRONTS DON JUAN APPROVED: \ Minor Professor Director of tfefe Department of English Dean of the Graduate Sci'iool THE JUVENALIAN INFLUENCE ON BYRON'S DON JUAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Diane Gardner Dunson, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1967 PREFACE This thesis is a comparative study of Juvenal and Lord Byron, with emphasis on the particularly kindred aspects of the poets' works. The two men lived hundreds of years apart, yet their ideas and attitudes are so similar that the con- nection bears research. In many instances, the relationship between the poets is only temperamental; at other times, the subject matter of Byron reveals the direct influence of Ju- venal. This paper treats in detail the major topics of in- terest which Juvenal and Byron shared—society, morality, war, death, and the purpose of life. The first chapter on' the nature of satire serves as an introduction to the study of these topics and is designed to bridge the time gap be- tween the poets. The backgrounds of Juvenal and Byron are considered briefly to show the comparable social and politi- cal atmosphere of their early manhood. The remaining three chapters deal in detail with the subject matter of Juvenal's Satires and Byron's Don Juan, with emphasis on the modernity, soundness of judgement, and worth of that which the two men have to say. For the particular study of the Juvenalian influence on Lord Byron, and especially on Don Juan, there were no iii specific books available. -

Double-Edged Imitation

Double-Edged Imitation Theories and Practices of Pastiche in Literature Sanna Nyqvist University of Helsinki 2010 © Sanna Nyqvist 2010 ISBN 978-952-92-6970-9 Nord Print Oy Helsinki 2010 Acknowledgements Among the great pleasures of bringing a project like this to com- pletion is the opportunity to declare my gratitude to the many people who have made it possible and, moreover, enjoyable and instructive. My supervisor, Professor H.K. Riikonen has accorded me generous academic freedom, as well as unfailing support when- ever I have needed it. His belief in the merits of this book has been a source of inspiration and motivation. Professor Steven Connor and Professor Suzanne Keen were as thorough and care- ful pre-examiners as I could wish for and I am very grateful for their suggestions and advice. I have been privileged to conduct my work for four years in the Finnish Graduate School of Literary Studies under the direc- torship of Professor Bo Pettersson. He and the Graduate School’s Post-Doctoral Researcher Harri Veivo not only offered insightful and careful comments on my papers, but equally importantly cre- ated a friendly and encouraging atmosphere in the Graduate School seminars. I thank my fellow post-graduate students – Dr. Juuso Aarnio, Dr. Ulrika Gustafsson, Dr. Mari Hatavara, Dr. Saija Isomaa, Mikko Kallionsivu, Toni Lahtinen, Hanna Meretoja, Dr. Outi Oja, Dr. Merja Polvinen, Dr. Riikka Rossi, Dr. Hanna Ruutu, Juho-Antti Tuhkanen and Jussi Willman – for their feed- back and collegial support. The rush to meet the seminar deadline was always amply compensated by the discussions in the seminar itself, and afterwards over a glass of wine. -

Ancient Authors 297

T Ancient authors 297 is unknown. His Attic Nights is a speeches for the law courts, collection of essays on a variety political speeches, philosophical ANCIENT AUTHORS of topics, based on his reading of essays, and personal letters to Apicius: (fourth century AD) is the Greek and Roman writers and the friends and family. name traditionally given to the lectures and conversations he had Columella: Lucius Iunius author of a collection of recipes, heard. The title Attic Nights refers Moderatus Columella (wrote c.AD de Re Coquinaria (On the Art of to Attica, the district in Greece 60–65) was born at Gades (modern Cooking). Marcus Gavius Apicius around Athens, where Gellius was Cadiz) in Spain and served in the was a gourmet who lived in the living when he wrote the book. Roman army in Syria. He wrote a early first centuryAD and wrote Cassius Dio (also Dio Cassius): treatise on farming, de Re Rustica about sauces. Seneca says that he Cassius Dio Cocceianus (c.AD (On Farming). claimed to have created a scientia 150–235) was born in Bithynia. He popīnae (snack bar cuisine). Diodorus Siculus: Diodorus had a political career as a consul (wrote c.60–30 BC) was a Greek Appian: Appianos (late first in Rome and governor of the from Sicily who wrote a history of century AD–AD 160s) was born in provinces of Africa and Dalmatia. the world centered on Rome, from Alexandria, in Egypt, and practiced His history of Rome, written in legendary beginnings to 54 BC. as a lawyer in Rome. -

Horace - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace(8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words." Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings". Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive to modern audiences. His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep") but for others he was, in < a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/john-henry-dryden/">John Dryden's</a> phrase, "a well-mannered court slave".