A Prescriptive Model for Utilizing Character and Personality In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* (Asterisk) in Google, 6 with Group Syntax, 215 in Name

CH27_228-236_Index.qxd 7/14/04 2:48 PM Page 229 INDEXINDEX * (asterisk) Applied Power, Principle of, brand names, 86–88 in Google, 6 102–106 Brooklyn Public Library, 119 with group syntax, 215 area codes, 169–170. See also browsers, 22–40 in name searches, 75 phone number searches bookmarklets with, 34–36 as wildcard, 6 art. See images gadgets for, 36–39 + (plus sign), 4–5. See also askanexpert.com, 93 iCab, 24 Boolean modifiers Ask Jeeves, 17–18 Internet Explorer, 23 – (minus sign), 4–5. See also for Kids, 210 listing, 25 Boolean modifiers toolbar, 32–33 Lynx, 24 | (pipe symbol), 5 associations Mozilla, 23 experts in, 91–93 Netscape, 23 finding, 92–93 Opera, 24 A audio, 154–163 plugins for, 27–29 finding, 159–160 Safari, 24–25 About.com, genealogy at, formats, 154–156 search toolbars with, 29–33 179–180 fun sites for, 162–163 security with, 25–26 address searches playing, 156–158 selecting, 25 driving directions and, 173 search engines/directories specialty toolbars with, 33 names in, 76–77 for, 160–162 speed optimization with, reverse lookups, 168–169 software sources, 158 26–27 229 for things/sites, 78 AU format, 155 turning off auto-password zip code helpers and, 172 reminders in, 26 AIFF format, 155 turning off Java in, 26 ALA Great Web Sites, 210 B turning off pop-ups in, 26 All Experts, 93–94 turning off scripting in, 25 AllPlaces, 134 Babelfish, 227 browser sniffer, 36–37 AlltheWeb, 160 BBB database, 195, 198 Bureau of Consumer Protection, almanacs, 186 Better Business Bureau, 195, 198 195 AltaVista, 148 biographical information, -

On the Fringe: a Practical Start-Up Guide to Creating, Assembling, and Evaluating a Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank ON THE FRINGE: A PRACTICAL START-UP GUIDE TO CREATING, ASSEMBLING, AND EVALUATING A FRINGE FESTIVAL IN PORTLAND, OREGON By Chelsea Colette Bushnell A Master’s Project Presented to the Arts and Administration program of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Science in Arts and Administration November 2004 1 ON THE FRINGE: A Practical Start-Up Guide to Creating, Assembling, and Evaluating a Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon Approved: _______________________________ Dr. Gaylene Carpenter Arts and Administration University of Oregon Date: ___________________ 2 © Chelsea Bushnell, 2004 Cover Image: Edinburgh Festival website, http://www.edfringe.com, November 12, 2004 3 Title: ON THE FRINGE: A PRACTICAL START-UP GUIDE TO CREATING, ASSEMBLING, AND EVALUATING A FRINGE FESTIVAL IN PORTLAND, OREGON Abstract The purpose of this study was to develop materials to facilitate the implementation of a seven- to-ten day Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon or any similar metro area. By definition, a Fringe Festival is a non-profit organization of performers, producers, and managers dedicated to providing local, national, and international emerging artists a non-juried opportunity to present new works to arts-friendly audiences. All Fringe Festivals are committed to a common philosophy that promotes accessible, inexpensive, and fun performing arts attendance. For the purposes of this study, qualitative research methods, supported by action research and combined with fieldwork and participant observations, will be used to investigate, describe, and document what Fringe Festivals are all about. -

Curriculum Materials

FIGHT BACK WITH LOVE: Every Adult Has a Responsibility to Prevent Bullying Curriculum Materials Endorsement: The Greater Phoenix Child Abuse Prevention Council is pleased to endorse the contents of this video series. If the victim is a child--Bullying is child abuse— whether done by an adult or another child. These videos are making an important contribution to child abuse prevention. Chairpersons, April 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS BY DESIGN--How to Use these videos and curriculum materials……………………….3 Why bullying is a focus today…………………………………………………………4 The BULLY……………………………………………………………………………………….7 The VICTIM……………………………………………………………………………………10 The BYSTANDER……………………………………………………………………………13 Gender Issues……………………………………………………………………………….15 Bullying in the community and workplace…………………………………..17 Handouts…………………………………………………………………………………….…18 Resources………………………………………………………………………………….....22 Copyright, 2003. Permission is given for duplication and use of all materials for educational purposes, not for commercial or for-profit uses. Citation credit to: Maricopa County Juvenile Probation Department FIGHT BACK WITH LOVE: Every Adult Has a Responsibility to Prevent Bullying Video and Curriculum Series http://www.superiorcourt.maricopa.gov/juvenileprob/ All materials have been created and prepared by the Maricopa County Juvenile Probation Dept. through grant funding from the Offices of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 2 By Design: How to use these videos and curriculum materials We have designed this set of videos to be as specific as possible to the behaviors and developmental phases of the two predominant age groups that fill our school campuses: the younger group, generally those beginning school through the fifth grade and the older group, roughly the middle school and high school students. Within these two groups studies have found that the discrete acts of bullying differ due to the developmental phases of the students but the goal of the bullying behavior is the same: dominance. -

“It's Gonna Be Some Drama!”: a Content Analytical Study Of

“IT’S GONNA BE SOME DRAMA!”: A CONTENT ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ON BET’S COLLEGE HILL _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by SIOBHAN E. SMITH Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2010 © Copyright by Siobhan E. Smith 2010 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “IT’S GONNA BE SOME DRAMA!”: A CONTENT ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ON BET’S COLLEGE HILL presented by Siobhan E. Smith, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz Professor Melissa Click Professor Ibitola Pearce Professor Michael J. Porter This work is dedicated to my unborn children, to my niece, Brooke Elizabeth, and to the young ones who will shape our future. First, all thanks and praise to God, from whom all blessings flow. For it was written: “I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me” (Philippians 4:13). My dissertation included! The months of all-nighters were possible were because You gave me strength; when I didn’t know what to write, You gave me the words. And when I wanted to scream, You gave me peace. Thank you for all of the people you have used to enrich my life, especially those I have forgotten to name here. -

In Communications Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research

Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications Spring 2011 Issue Published by the School of Communications Elon University Joining the World of Journals Welcome to the nation’s first and, to our knowledge, only undergraduate research journal in communi- cations. We discovered this fact while perusing the Web site of the Council on Undergraduate Research, which lists and links to the 60 or so undergraduate research journals nationwide (http://www.cur.org/ugjournal. html). Some of these journals focus on a discipline (e.g., Journal of Undergraduate Research in Physics), some are university-based and multidisciplinary (e.g., MIT Undergraduate Research Journal), and some are university-based and disciplinary (e.g., Furman University Electronic Journal in Undergraduate Mathematics). The Elon Journal is the first to focus on undergraduate research in journalism, media and communi- cations. The School of Communications at Elon University is the creator and publisher of the online journal. The first issue was published in Spring 2010 under the editorship of Dr. Byung Lee, associate professor in the School of Communications. The three purposes of the journal are: • To publish the best undergraduate research in Elon’s School of Communications each term, • To serve as a repository for quality work to benefit future students seeking models for how to do undergraduate research well, and • To advance the university’s priority to emphasize undergraduate student research. The Elon Journal is published twice a year, with spring and fall issues. Articles and other materials in the journal may be freely downloaded, reproduced and redistributed without permission as long as the author and source are properly cited. -

Health and Environmental Justice (HEJ)

Part Three: General Plan Elements – Health and Environmental Justice Health and Environmental Justice (HEJ) A. Introduction Public Health - A The way we design and build the human environment has a state of complete profound impact on both public health and environmental physical, mental, justice. Planning decisions related to transportation and social systems, density and intensity of uses, land use practices, wellbeing, not just and street design influence: how much we walk, ride a the absence of disease or bicycle, drive a car, or take public transportation; the level infirmity. (World of our stress; the types of food we eat; and the quality of Health our air and water – all factors which affect our health. For Organization) example, the more we drive, the more our vehicles emit Environmental harmful gases and particles into the air, which can lead to Justice – The fair respiratory problems such as asthma. A compact, mixed-use treatment and development pattern that reduces reliance on automobiles meaningful and increases public transit opportunities can improve air participation of quality and respiratory health1. people of all races, cultures, and incomes with In addition, the presence or absence of sidewalks and bike respect to the routes, heavy traffic, hills, street lights, enjoyable scenery, development, and observations of others exercising all impact our level of adoption, 2 implementation, physical activity . Regular physical activity is important to and enforcement build and maintain healthy bones, muscles, and joints and to of environmental help reduce the risk of developing heart disease, diabetes, laws, regulations, high blood pressure, colon and breast cancer, obesity, and and policies. -

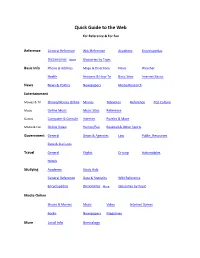

Quick Guide to the Web

Quick Guide to the Web For Reference & For Fun Reference General Reference Wiki Reference Academic Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Basic Info Phone & Address Maps & Directions News Weather Health Answers & How-To Basic Sites Internet Basics News News & Politics Newspapers Media Research Entertainment Movies & TV Shows/Movies Online Movies Television Reference Pop Culture Music Online Music Music Sites Reference Games Computer & Console Internet Puzzles & More Media & Fun Online Video Humor/Fun Baseball & Other Sports Government General Depts & Agencies Law Public_Resources Data & Statistics Travel General Flights Driving Automobiles Hotels Studying Academic Study Aids General Reference Data & Statistics Wiki Reference Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Media Online Shows & Movies Music Video Internet Games Books Newspapers Magazines More Local Info Genealogy Finding Basic Information Basic Search & More Google Yahoo Bing MSN ask.com AOL Wikipedia About.com Internet Public Library Freebase Librarian Chick DMOZ Open Directory Executive Library Web Research OEDB LexisNexis Wayback Machine Norton Site-Checker DigitalResearchTools Web Rankings Alexa Web Tools - Librarian Chick Web 2.0 Tools Top Reference & Resources – Internet Quick Links E-map | Indispensable Links | All My Faves | Joongel | Hotsheet | Quick.as Corsinet | Refdesk Tools | CEO Express Internet Resources Wayback Machine | Alexa | Web Rankings | Norton Site-Checker Useful Web Tools DigitalResearchTools | FOSS Wiki | Librarian Chick | Virtual -

Product Placement Effectiveness: Revisited and Renewed

Journal of Management and Marketing Research Product placement effectiveness: revisited and renewed Kaylene Williams California State University, Stanislaus Alfred Petrosky California State University, Stanislaus Edward Hernandez California State University, Stanislaus Robert Page, Jr. Southern Connecticut State University ABSTRACT Product placement is the purposeful incorporation of commercial content into non- commercial settings, that is, a product plug generated via the fusion of advertising and entertainment. While product placement is riskier than conventional advertising, it is becoming a common practice to place products and brands into mainstream media including films, broadcast and cable television programs, computer and video games, blogs, music videos/DVDs, magazines, books, comics, Broadway musicals and plays, radio, Internet, and mobile phones. To reach retreating audiences, advertisers use product placements increasingly in clever, effective ways that do not cost too much. The purpose of this paper is to examine product placement in terms of definition, use, purposes of product placement, specific media vehicles, variables that impact the effectiveness of product placement, the downside of using product placement, and the ethics of product placement. Keywords: Product placement, brand placement, branded entertainment, in-program sponsoring Product placement effectiveness, Page 1 Journal of Management and Marketing Research INTRODUCTION In its simplest form, product placement consists of an advertiser or company producing -

Open Colatedfinal.Doc.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Special Individualized Interdisciplinary Doctoral Major GIRLING THE GIRL: VISUAL CULTURE AND GIRL STUDIES A Dissertation in Women’s Studies and Visual Culture by Leisha Jones 2008 Leisha Jones Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2008 The dissertation of Leisha Jones was reviewed and approved* by the following: Janet Lyon Associate Professor of English , Women’s Studies, and Science, Technology, and Society Chair of Committee, Dissertation Advisor Richard Doyle Professor of English/Science, Technology, and Society/Information Science and Technology Yvonne Gaudelius Professor of Art Education and Women’s Studies Assistant Vice President and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education Susan Squier Brill Professor of Women's Studies, English, and Science, Technology, and Society Vincent Colapietro Professor of Philosophy Mark Wardell Associate Professor of Labor Studies and Industrial Relations and Sociology Associate Dean of Graduate Student Affairs and Director of the Special Individualized Interdisciplinary Doctoral Major *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Caught between lipstick and a field hockey stick, girls invent tactics for assembling themselves as performative multiplicities, individual hordes of desire that mutate as often as they change shoes. This dissertation offers a research model for feminism that addresses girls as positive categories of possibility, that revalues the status of girls as to- be subjects, and that develops a synthesis between Visual Culture, Women’s Studies, and the emerging field of Girl Studies. The analyses produced by this model are deliberately unhinged from the kind of psychological moorings that predetermine girl as a marker for woman-in-training. -

Broadband: the Revolution Underway

RESEARCH ON STRATEGIC CHANGE January 2004 Broadband: The Revolution Underway Critical Issues and Investment Implications ■ What are the risks and opportunities for cable and telecom firms? ■ How will broadband affect consumer electronics? ■ How will video be distributed? ■ Will the balance of power shift between content producers and distributors? ■ What will PVRs, VOD and Internet Protocol technology mean for advertising? www.alliancecapital.com BROADBAND: THE REVOLUTION UNDERWAY Executive Summary As of September 30, 2003, approximately 29% of Internet subscribers around the world paid for broadband access. Since 2000, the number of broadband subscribers has increased at a compound annual growth rate of 136%, reaching an already impressive 86 million subscribers. We believe this growth will continue at a rapid pace and have vast implications for the providers of telecom services, cable, consumer electronics, personal computers, entertainment content and advertising, as well as participants in a number of other industries. In this report, we explain why broadband penetration rates will continue to rise and discuss the consequences of this phenomenon. The consequences include: ■ Continued pressure on pricing for wireline voice services; ■ A new cycle of digitized and networked consumer-electronics products; ■ The encroachment of the PC into the traditional domain of consumer-electronics firms; ■ The rise of new competitors that capitalize on the capabilities of broadband and the power of home networks; ■ New entrants in video distribution; ■ A greater supply of niche video content; ■ A general shift in the balance of power in favor of content producers; and ■ The rollout of Internet Protocol TV and the rise of niche advertising. A Message from Our CEO “Broadband: The Revolution Underway” is the first in a series of studies planned by a new Alliance Capital research unit focused on strategic change. -

Fear and Norms and Rock & Roll: What Jambands Can Teach Us About

FEAR AND NORMS AND ROCK & ROLL: WHAT JAMBANDS CAN TEACH US ABOUT PERSUADING PEOPLE TO OBEY COPYRIGHT LAW By Mark F. Schultz† TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................653 II. SOCIAL NORMS: WHO NEEDS THEM?............................................658 A. THE CHANGING NATURE OF MUSIC PIRACY........................................658 B. THE PROBLEM WITH DETERRENCE-BASED STRATEGIES .....................661 C. NORMATIVE STRATEGIES.....................................................................665 III. THE JAMBAND COMMUNITY: A CASE STUDY IN VOLUNTARY COMPLIANCE..............................................................668 A. A BRIEF HISTORY OF JAMBANDS .........................................................668 B. A CASE STUDY OF A RECIPROCATING COMMUNITY............................675 1. Asserting and Giving Up Control..................................................676 2. A Community Founded on Sharing Music.....................................677 3. Setting Rules ..................................................................................680 4. Playing by the Rules ......................................................................681 5. A Reciprocal Relationship.............................................................688 6. New Distribution Models...............................................................689 7. Summary........................................................................................691 IV. EXPLAINING THE SOCIAL -

Guide for Contributors

Celt ISSN: 1412-3320 A Journal of Culture, English Language Teaching & Literature Learners' Language Challenges in Writing English Barli Bram ....................................................................................................... 1 Autonomous Learning in Elle: Cybernautical Approach as the Viaduct to L2 Acquisition Jacob George C. ............................................................................................ 16 Scrooge's Character Development in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol Theresia Erwindriani .................................................................................... 28 Teaching English with Drama for Young Learners: Skill or Confidence? G.M. Adhyanggono ....................................................................................... 45 “America, You Know What I'm Talkin' About!”: Race, Class, and Gender in Beulah and Bernie Mac Angela Nelson ............................................................................................... 60 A Love for Indonesia: The Youth's Effort in Increasing Honor Towards Multiculturalism Shierly June and Ekawati Marhaenny Dukut ................................................. 72 A Book Review: Discourse Analysis Antonius Suratno ........................................................................................... 88 Celt, Vol.12, No.1, pp. 1-100, Semarang, Juli 2012 (Index) “AMERICA, YOU KNOW WHAT I’M TALKIN’ ABOUT!”: RACE, CLASS, AND GENDER IN BEULAH AND BERNIE MAC Angela Nelson1 Abstract: This paper compares and contrasts The Beulah Show