Open Colatedfinal.Doc.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Yarns and Funny Jokes

f IMfWtMTYLIBRARY^)Of AUKJUNIA h SAMMMO ^^F -J) NEW YARNS AND COMPRISING ORIGINAL AND SELECTED MERIGAN * HUMOR WITH MANY LAUGHABLE ILLUSTRATIONS. Copyright, 1890, by EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE. NEW YORK* EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSB, 29 & 3 1 Beekman Street EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE, 29 &. 31 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. PAYNE'S BUSINESS EDUCATOR AN- ED cyclopedia of the Knowl* edge necessary to the Conduct of Business, AMONG THE CONTENTS ARE: An Epitome of the Laws of the various States of the Union, alphabet- ically arranged for ready reference ; Model Business Letters and Answers ; in Lessons Penmanship ; Interest Tables ; Rules of Order for Deliberative As- semblies and Debating Societies Tables of Weights and Measures, Stand- ard and the Metric System ; lessons in Typewriting; Legal Forms for all Instruments used in Ordinary Business, such as Leases, Assignments, Contracts, etc., etc.; Dictionary of Mercantile Terms; Interest Laws of the United States; Official, Military, Scholastic, Naval, and Professional Titles used in U. S.; How to Measure Land ; in Yalue of Foreign Gold and Silver Coins the United states ; Educational Statistics of the World ; List of Abbreviations ; and Italian and Phrases Latin, French, Spanish, Words -, Rules of Punctuation ; Marks of Accent; Dictionary of Synonyms; Copyright Law of the United States, etc., etc., MAKING IN ALL THE MOST COMPLETE SELF-EDUCATOR PUBLISHED, CONTAINING 600 PAGES, BOUND IN EXTRA CLOTH. PRICE $2.00. N.B.- LIBERAL TERMS TO AGENTS ON THIS WORK. The above Book sent postpaid on receipt of price. Yar]Qs Jokes. ' ' A Natural Mistake. Well, Jim was champion quoit-thrower in them days, He's dead now, poor fellow, but Jim was a boss on throwing quoits. -

Rock Legends to Perform at the 2018 Illinois State Fair

For Immediate Release Contacts: March 19, 2018 Rebecca Clark (217) 558-1546 Morgan Booth (217) 785-5485 ROCK LEGENDS TO PERFORM AT THE 2018 ILLINOIS STATE FAIR Springfield, IL – This August, Ag Director Raymond Poe and State Fair Manager Luke Sailer are proud to welcome rock legends Foreigner and Joan Jett & the Blackhearts to the Illinois Lottery Grandstand stage on Sunday, August 12 at 2018 Illinois State Fair. Foreigner is among the top 40 best-selling music artists of all time, according to Business Insider magazine. The group is universally known as one of the most popular acts in the rock world with a playlist that continues to sell out tours and albums. While the band has been around for more than 40 years, a younger generation is exposed to the band’s music through popular films and television shows such as, “Rock of Ages,” “Orange Is The New Black,” “Kung Fu Panda 3,” and “Stranger Things.” Foreigner is best known for anthems such as, “Juke Box Hero,” “Cold As Ice,” “Feels Like the First Time,” “I Want to Know What Love Is,” and “Waiting for a Girl Like You.” Joan Jett is an originator, an innovator, and a visionary. As the leader of the hard- rocking Blackhearts, with whom she has become a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee, she’s had eight platinum and gold albums and nine Top 40 singles, including the classics "Bad Reputation," "I Love Rock 'N' Roll," "I Hate Myself For Loving You," and "Crimson and Clover." Her independent record label, Blackheart, was founded in 1980 after she was rejected by no less than 23 labels. -

* (Asterisk) in Google, 6 with Group Syntax, 215 in Name

CH27_228-236_Index.qxd 7/14/04 2:48 PM Page 229 INDEXINDEX * (asterisk) Applied Power, Principle of, brand names, 86–88 in Google, 6 102–106 Brooklyn Public Library, 119 with group syntax, 215 area codes, 169–170. See also browsers, 22–40 in name searches, 75 phone number searches bookmarklets with, 34–36 as wildcard, 6 art. See images gadgets for, 36–39 + (plus sign), 4–5. See also askanexpert.com, 93 iCab, 24 Boolean modifiers Ask Jeeves, 17–18 Internet Explorer, 23 – (minus sign), 4–5. See also for Kids, 210 listing, 25 Boolean modifiers toolbar, 32–33 Lynx, 24 | (pipe symbol), 5 associations Mozilla, 23 experts in, 91–93 Netscape, 23 finding, 92–93 Opera, 24 A audio, 154–163 plugins for, 27–29 finding, 159–160 Safari, 24–25 About.com, genealogy at, formats, 154–156 search toolbars with, 29–33 179–180 fun sites for, 162–163 security with, 25–26 address searches playing, 156–158 selecting, 25 driving directions and, 173 search engines/directories specialty toolbars with, 33 names in, 76–77 for, 160–162 speed optimization with, reverse lookups, 168–169 software sources, 158 26–27 229 for things/sites, 78 AU format, 155 turning off auto-password zip code helpers and, 172 reminders in, 26 AIFF format, 155 turning off Java in, 26 ALA Great Web Sites, 210 B turning off pop-ups in, 26 All Experts, 93–94 turning off scripting in, 25 AllPlaces, 134 Babelfish, 227 browser sniffer, 36–37 AlltheWeb, 160 BBB database, 195, 198 Bureau of Consumer Protection, almanacs, 186 Better Business Bureau, 195, 198 195 AltaVista, 148 biographical information, -

On the Fringe: a Practical Start-Up Guide to Creating, Assembling, and Evaluating a Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank ON THE FRINGE: A PRACTICAL START-UP GUIDE TO CREATING, ASSEMBLING, AND EVALUATING A FRINGE FESTIVAL IN PORTLAND, OREGON By Chelsea Colette Bushnell A Master’s Project Presented to the Arts and Administration program of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Science in Arts and Administration November 2004 1 ON THE FRINGE: A Practical Start-Up Guide to Creating, Assembling, and Evaluating a Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon Approved: _______________________________ Dr. Gaylene Carpenter Arts and Administration University of Oregon Date: ___________________ 2 © Chelsea Bushnell, 2004 Cover Image: Edinburgh Festival website, http://www.edfringe.com, November 12, 2004 3 Title: ON THE FRINGE: A PRACTICAL START-UP GUIDE TO CREATING, ASSEMBLING, AND EVALUATING A FRINGE FESTIVAL IN PORTLAND, OREGON Abstract The purpose of this study was to develop materials to facilitate the implementation of a seven- to-ten day Fringe Festival in Portland, Oregon or any similar metro area. By definition, a Fringe Festival is a non-profit organization of performers, producers, and managers dedicated to providing local, national, and international emerging artists a non-juried opportunity to present new works to arts-friendly audiences. All Fringe Festivals are committed to a common philosophy that promotes accessible, inexpensive, and fun performing arts attendance. For the purposes of this study, qualitative research methods, supported by action research and combined with fieldwork and participant observations, will be used to investigate, describe, and document what Fringe Festivals are all about. -

Curriculum Materials

FIGHT BACK WITH LOVE: Every Adult Has a Responsibility to Prevent Bullying Curriculum Materials Endorsement: The Greater Phoenix Child Abuse Prevention Council is pleased to endorse the contents of this video series. If the victim is a child--Bullying is child abuse— whether done by an adult or another child. These videos are making an important contribution to child abuse prevention. Chairpersons, April 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS BY DESIGN--How to Use these videos and curriculum materials……………………….3 Why bullying is a focus today…………………………………………………………4 The BULLY……………………………………………………………………………………….7 The VICTIM……………………………………………………………………………………10 The BYSTANDER……………………………………………………………………………13 Gender Issues……………………………………………………………………………….15 Bullying in the community and workplace…………………………………..17 Handouts…………………………………………………………………………………….…18 Resources………………………………………………………………………………….....22 Copyright, 2003. Permission is given for duplication and use of all materials for educational purposes, not for commercial or for-profit uses. Citation credit to: Maricopa County Juvenile Probation Department FIGHT BACK WITH LOVE: Every Adult Has a Responsibility to Prevent Bullying Video and Curriculum Series http://www.superiorcourt.maricopa.gov/juvenileprob/ All materials have been created and prepared by the Maricopa County Juvenile Probation Dept. through grant funding from the Offices of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 2 By Design: How to use these videos and curriculum materials We have designed this set of videos to be as specific as possible to the behaviors and developmental phases of the two predominant age groups that fill our school campuses: the younger group, generally those beginning school through the fifth grade and the older group, roughly the middle school and high school students. Within these two groups studies have found that the discrete acts of bullying differ due to the developmental phases of the students but the goal of the bullying behavior is the same: dominance. -

Joan Jett & the Blackhearts

Joan Jett & the Blackhearts By Jaan Uhelszki As leader of her hard-rockin’ band, Jett has influenced countless young women to pick up guitars - and play loud. IF YOU HAD TO SIT DOWN AND IMAGINE THE IDEAL female rocker, what would she look like? Tight leather pants, lots of mascara, black (definitely not blond) hair, and she would have to play guitar like Chuck Berry’s long-lost daughter. She wouldn’t look like Madonna or Taylor Swift. Maybe she would look something like Ronnie Spector, a little formidable and dangerous, definitely - androgynous, for sure. In fact, if you close your eyes and think about it, she would be the spitting image of Joan Jett. ^ Jett has always brought danger, defiance, and fierceness to rock & roll. Along with the Blackhearts - Jamaican slang for loner - she has never been afraid to explore her own vulnerabilities or her darker sides, or to speak her mind. It wouldn’t be going too far to call Joan Jett the last American rock star, pursuing her considerable craft for the right reason: a devo tion to the true spirit of the music. She doesn’t just love rock & roll; she honors it. ^ Whether she’s performing in a blue burka for U.S. troops in Afghanistan, working for PETA, or honoring the slain Seattle singer Mia Zapata by recording a live album with Zapata’s band the Gits - and donating the proceeds to help fund the investigation of Zapata’s murder - her motivation is consistent. Over the years, she’s acted as spiritual advisor to Ian MacKaye, Paul Westerberg, and Peaches. -

“It's Gonna Be Some Drama!”: a Content Analytical Study Of

“IT’S GONNA BE SOME DRAMA!”: A CONTENT ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ON BET’S COLLEGE HILL _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by SIOBHAN E. SMITH Dr. Jennifer Stevens Aubrey, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2010 © Copyright by Siobhan E. Smith 2010 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “IT’S GONNA BE SOME DRAMA!”: A CONTENT ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE PORTRAYALS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AND HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES ON BET’S COLLEGE HILL presented by Siobhan E. Smith, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Jennifer Stevens Aubrey Professor Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz Professor Melissa Click Professor Ibitola Pearce Professor Michael J. Porter This work is dedicated to my unborn children, to my niece, Brooke Elizabeth, and to the young ones who will shape our future. First, all thanks and praise to God, from whom all blessings flow. For it was written: “I can do all things through Christ which strengthens me” (Philippians 4:13). My dissertation included! The months of all-nighters were possible were because You gave me strength; when I didn’t know what to write, You gave me the words. And when I wanted to scream, You gave me peace. Thank you for all of the people you have used to enrich my life, especially those I have forgotten to name here. -

The Runaways

The Runaways The Runaways 1 / 3 2 / 3 Just 40 years after they played their final show, Joan Jett has revealed what caused the breakup of punk icons The Runaways. Formed in Los .... Listen to music from The Runaways like Cherry Bomb, You Drive Me Wild & more. Find the latest tracks, albums, and images from The Runaways.. The Runaways is a 2010 American biographical drama film about the 1970s rock band of the same name written and directed by Floria Sigismondi. It is based .... In 1974, when she was only 14, Jackie Fuchs would wake up way before her parents and catch a ride with friends from her house in the San Fernando Valley .... From Black Panther to Clueless, Dazed and Confused to Purple Rain, the music that has defined modern filmmaking. by: Pitchfork. February 19 2019.. The Runaways. 361K likes. The Official Facebook Page for The Runaways.. The Runaways were an all- female teenage American rock band that recorded and performed in the second half of the 1970s. The band released four studio albums and one live set during its run.. The Runaways were an American all-female hard rock band (1975-1979) The group, assisted by producer Kim Fowley, consisted initially of singer/guitarist Joan Jett, bassist Michael Steele and drummer Sandy West. The latest Tweets from The Runaways (@TheRunaways). Official account of the pioneering all-female rock band.. A coming- of-age biographical film about the 1970s teenage all-girl rock band The Runaways. The relationship between band members Cherie Currie and Joan Jett is also explored. -

In Communications Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research

Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications Spring 2011 Issue Published by the School of Communications Elon University Joining the World of Journals Welcome to the nation’s first and, to our knowledge, only undergraduate research journal in communi- cations. We discovered this fact while perusing the Web site of the Council on Undergraduate Research, which lists and links to the 60 or so undergraduate research journals nationwide (http://www.cur.org/ugjournal. html). Some of these journals focus on a discipline (e.g., Journal of Undergraduate Research in Physics), some are university-based and multidisciplinary (e.g., MIT Undergraduate Research Journal), and some are university-based and disciplinary (e.g., Furman University Electronic Journal in Undergraduate Mathematics). The Elon Journal is the first to focus on undergraduate research in journalism, media and communi- cations. The School of Communications at Elon University is the creator and publisher of the online journal. The first issue was published in Spring 2010 under the editorship of Dr. Byung Lee, associate professor in the School of Communications. The three purposes of the journal are: • To publish the best undergraduate research in Elon’s School of Communications each term, • To serve as a repository for quality work to benefit future students seeking models for how to do undergraduate research well, and • To advance the university’s priority to emphasize undergraduate student research. The Elon Journal is published twice a year, with spring and fall issues. Articles and other materials in the journal may be freely downloaded, reproduced and redistributed without permission as long as the author and source are properly cited. -

Excellent Tool for Standardized Test Preparation!

Excellent Tool for Standardized Test Preparation! • Latin and Greek roots • Figurative language • Reading comprehension • Fact and opinion • Predicting outcomes • Answer key Reading Grade 6 Frank Schaffer Publications® Spectrum is an imprint of Frank Schaffer Publications. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher, unless otherwise indicated. Frank Schaffer Publications is an imprint of School Specialty Publishing. Copyright © 2007 School Specialty Publishing. Send all inquiries to: Frank Schaffer Publications 8720 Orion Place Columbus, Ohio 43240-2111 Spectrum Reading—grade 6 ISBN 978-0-76823-826-6 Index of Skills Reading Grade 6 Numerals indicate the exercise pages on which these skills appear. Vocabulary Skills Drawing Conclusions 3, 7, 17, 23, 25, 29, 31, 33, 41, 43, 47, 51, 61, 65, 75, 79, 87, 89, 93, 95, 97, 99, 101, Abbreviations 5, 11, 15, 27, 39, 59, 61, 69, 79, 81, 103, 107, 109, 113, 117, 121, 123, 127, 133, 135, 111 139, 143, 151 Affixes 3, 9, 21, 29, 35, 51, 59, 65, 71, 77, 89, 95, Fact and Opinion 7, 31, 45, 53, 71, 83, 99, 115 109, 111, 117, 123, 125 Facts and Details all activity pages Antonyms 13, 31, 45, 53, 61, 67, 83, 91, 105, 135, 141 Fantasy and Reality 39, 57, 125, 143 Classification 5, 21, 41, 55, 125, 137, 151 Formulates Ideas and Opinions 103, 107, -

Health and Environmental Justice (HEJ)

Part Three: General Plan Elements – Health and Environmental Justice Health and Environmental Justice (HEJ) A. Introduction Public Health - A The way we design and build the human environment has a state of complete profound impact on both public health and environmental physical, mental, justice. Planning decisions related to transportation and social systems, density and intensity of uses, land use practices, wellbeing, not just and street design influence: how much we walk, ride a the absence of disease or bicycle, drive a car, or take public transportation; the level infirmity. (World of our stress; the types of food we eat; and the quality of Health our air and water – all factors which affect our health. For Organization) example, the more we drive, the more our vehicles emit Environmental harmful gases and particles into the air, which can lead to Justice – The fair respiratory problems such as asthma. A compact, mixed-use treatment and development pattern that reduces reliance on automobiles meaningful and increases public transit opportunities can improve air participation of quality and respiratory health1. people of all races, cultures, and incomes with In addition, the presence or absence of sidewalks and bike respect to the routes, heavy traffic, hills, street lights, enjoyable scenery, development, and observations of others exercising all impact our level of adoption, 2 implementation, physical activity . Regular physical activity is important to and enforcement build and maintain healthy bones, muscles, and joints and to of environmental help reduce the risk of developing heart disease, diabetes, laws, regulations, high blood pressure, colon and breast cancer, obesity, and and policies. -

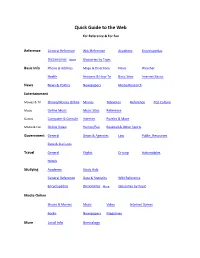

Quick Guide to the Web

Quick Guide to the Web For Reference & For Fun Reference General Reference Wiki Reference Academic Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Basic Info Phone & Address Maps & Directions News Weather Health Answers & How-To Basic Sites Internet Basics News News & Politics Newspapers Media Research Entertainment Movies & TV Shows/Movies Online Movies Television Reference Pop Culture Music Online Music Music Sites Reference Games Computer & Console Internet Puzzles & More Media & Fun Online Video Humor/Fun Baseball & Other Sports Government General Depts & Agencies Law Public_Resources Data & Statistics Travel General Flights Driving Automobiles Hotels Studying Academic Study Aids General Reference Data & Statistics Wiki Reference Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Media Online Shows & Movies Music Video Internet Games Books Newspapers Magazines More Local Info Genealogy Finding Basic Information Basic Search & More Google Yahoo Bing MSN ask.com AOL Wikipedia About.com Internet Public Library Freebase Librarian Chick DMOZ Open Directory Executive Library Web Research OEDB LexisNexis Wayback Machine Norton Site-Checker DigitalResearchTools Web Rankings Alexa Web Tools - Librarian Chick Web 2.0 Tools Top Reference & Resources – Internet Quick Links E-map | Indispensable Links | All My Faves | Joongel | Hotsheet | Quick.as Corsinet | Refdesk Tools | CEO Express Internet Resources Wayback Machine | Alexa | Web Rankings | Norton Site-Checker Useful Web Tools DigitalResearchTools | FOSS Wiki | Librarian Chick | Virtual