Prelude to the Voting Rights Act: the Suffrage Crusade, 1962-1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Algebra Project Newsletter

December 15, 2020 NEWSLETTER Math Literacy | Is the Key | to 21st Century Citizenship! A student’s math Student voices his math literacy journey: Jevonnie literacy journey: I struggled through middle school. I barely made it to high school. The Jevonnie, p. 1 summer between 8th and 9th grade all athletes were required to be involved with the Young People’s Project Jevonnie, a high school senior (YPP) and the Algebra Project. I was really in Broward County, FL, shares not optimistic because it was doing math in the summer and all I wanted to do was his math literacy journey. work out and play football. But it was a totally different experience than what I Bob Moses & Henry envisioned it to be. The Algebra Project Hipps’ Fireside classroom when we started school was the Chat, link: p same. I was like, “oh, my gosh! I have math at 7:30 in the morning, every day.” Then I went and I was like… “wow this doesn’t feel The Algebra Project like a math class.” For the majority of the class you are not sitting down. in Broward County You are walking around, collaborating, talking with your friends, your peers, doing work with them. Ms. Caicedo is breaking things down. We Public Schools - would be so intrigued and involved in the lesson.… video highlights, p.2 As a YPP Math Literacy Worker (MLW) I got to see things outside of what my mind was always fixed on, which was sports. The kids came in Office of Academics: https:// and we started teaching them and I got to see the ‘mini-me’s’ – I got to www.browardschools.com/ see how I was in them. -

Nandita Kathiresan the Forgotten Voices

Nandita Kathiresan The Forgotten Voices in the Fight to Suffrage Political cartoons are unique in the sense that they allocate many interpretations regarding a critical matter based on an individual's outlook of their environment. People of all backgrounds have a special ability to interpret these visuals differently which presents the issue, such as the effects of slavery, in diverse ways as opposed to words on paper. To begin, since the colonization of the United States, slavery was a broad topic that encompassed most, in not all parts of living during the time period. African-American men and women were restricted basic rights up until the end of the Civil War, where they were considered citizens, yet lacked the privilege of suffrage. After the 15th amendment, all men were granted this right, yet women were not presented with such a freedom. Consequently, during the time period of the mid-1800s, women within the country decided to share their voice surrounding the topic of suffrage. The rapidly changing environment in the country gave women the power and strength to fight for this piece of freedom during the Reconstruction Era in numerous marches, such as the Women’s Suffrage Procession. However, it is merely assumed that all women contributed as an equal voice to this important cause, yet black women fell short asserting their voices. This was not due to a lack of passion—rather is the suppression of the freedom of speech covered up by the white, female protesters. Despite living in a country with rapid, positive changes in society, black women were often the forgotten voices fighting for suffrage despite their hidden voice pleading for reform in the late 1800s. -

The First Section of This Document Narrates Southern Resistance to Integration from 1964 to 1967

q. # DOCUMENT RESUME ED 033.18 . VD 009..1,54. IMO . .. By-Bartley. Glenda: And Others Lawlessness and Disorder: Fourteen Years of Failure in Southern School Desegregation. Special Report. Southern Regional Council. Atlanta. Ca. Pub Date 1681 Note-66p. EDRS Price MF -$0.50 HC -$3.40 Descriptors -*Civil Rights Legislation. Discriminatory Legislation. Federal Government. Free Choice Transfer Programs. Integration Litigation. Law Enforcement. RacialIntegration. School Integration. School Segregation. Southern Attitudes. Southern Schools Identifiers-Alabama. Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title VI. Jefferson County. Macon County. U S Congress The first section of this document narrates Southern resistance to integration from 1964 to 1967. and the second relates the weakening of civil rights legislation through the influence of Southern Congressmen and other moderates in Congress. A detailed discussion of the Macon County and Jefferson County (Alabama) school desegregation decisions is presented in the Appendix. Charts are included. (KG) ANL 11111 OM_ SOUTHERN REGIONAL COUNCIL 5 Forsyth Street, N.W., Atlanta 3, Georgia LAWLESSNESS AND DISORDER Fourteen Years of Failurein Southern School Desegregation U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT.POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS, STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. LAWLESSNESS AND DISORDER Fourteen Years of Failure in Southern School Desegregation Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out F. the mote out of thy brother's eye. --Matthell, 7:5. Introduction. This report is the third in a period of four yearsin which the Southern Regional Council has attempted totell the nation of the deplorable degree of failurein the South to comply with the law of the land againstracial discrim- ination in education, and to suggest the terribleimplica- tions of this failure. -

V Proof of Residence for Voter Registration

v Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration What Do I Need To Know About Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration? A Proof of Residence document is a document that proves where you live in Wisconsin and is only used when registering to vote. Photo ID is separate, you only show photo ID to prove who you are when you request an absentee ballot or receive a ballot at your polling place. When Do I Have To Provide Proof Of Residence? All voters MUST provide a Proof of Residence Document. If you register to vote by mail, in-person in your clerk’s office, with a Election Registration Official, or at your polling place on Election Day, you need to provide a Proof of Residence document. * If you are an active military voter, or a permanent overseas voter (with no intent to return to the U.S.) you do not need to provide a Proof of Residence document. What Documents Can I Use As Proof Of Residence For Registering? All Proof of Residence documents must include the voter’s name and current residential address. • A current and valid State of Wisconsin Driver License or State ID card. • Any other official identification card or license issued by a Wisconsin governmental body or unit. • Any identification card issued by an employer in the normal course of business and bearing a photo of the card holder, but not including a business card. • A real estate tax bill or receipt for the current year or the year preceding the date of the election. • A university, college, or technical college identification card (must include photo) ONLY if the voter provides a fee receipt dated within the last 9 months or the institution provides a certified housing list, that indicates citizenship, to the municipal clerk. -

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in Mccomb, Mississippi, 1928-1964

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in McComb, Mississippi, 1928-1964 Alec Ramsay-Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2016 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For Dana Lynn Ramsay, I would not be here without your love and wisdom, And I miss you more every day. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: McComb and the Beginnings of Voter Registration .......................... 10 Chapter Two: SNCC and the 1961 McComb Voter Registration Drive .................. 45 Chapter Three: The Aftermath of the McComb Registration Drive ........................ 78 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 102 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 119 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have done this without my twin sister Hunter Ramsay-Smith, who has been a constant source of support and would listen to me rant for hours about documents I would find or things I would learn in the course of my research for the McComb registration -

The Making.Indd

PRIMARY SOURCE DOCUMENTARIES: The Making of “We’ll Never Turn Back” (1963) and “Dream Deferred” (1964) by Harvey Richards Written by Paul Richards, Ph.D. Photos by Harvey Richards In 1963 and 1964, my father, Harvey Richards, made two fi lms about the voter registration drives in Mississippi as part of the movement to end racial segregation in the United States. The fi lms are “We’ll Never Turn Back” (1963) and “Dream Deferred” (1964). They were a collaboration be- tween Harvey and Amzie Moore, a Cleveland, Mississippi resident and long time civil rights activist, designed to help organize and raise funds for the Student Non Violent Coor- dinating Committee (SNCC). The following is the story of how these fi lms were made. Late one February night in 1963, Harvey Richards drove his Oldsmobile station wagon full of sound and camera equip- ment, sporting a California license plate, up to the front door of Amzie Moore’s house in Cleveland, Mississippi. Cleve- land, Mississippi is a small delta town in the northern part of the state, about half a day’s drive from New Orleans, Loui- Harvey Richards (baseball cap) meeting with Amzie Moore (white overcoat) and (left to right) E.W.Steptoe, Bob Moses and unidentifi ed man. siana, where Harvey had spent the previous night. Amzie Moore opened his door and the two men, both 51 years old, met for the fi rst time. Harvey was around 6 foot tall, trim at 180 pounds, dressed in a warm canvas jacket and kaiki baseball cap. Amzie dressed in a plaid shirt and worn kaki pants, looked out his front door at this unannounced white stranger. -

Remembering the Struggle for Civil Rights – the Greenwood Sites

rallied a crowd of workers set up shop in a building that stood Union Grove M.B. Church protestors in this park on this site. By 1963, local participation in 615 Saint Charles Street with shouts of “We Civil Rights activities was growing, accel- Union Grove was the first Baptist church in want black power!” erated by the supervisors’ decision to halt Greenwood to open its doors to Civil Rights Change Began Here Greenwood was the commodity distribution. The Congress of activities when it participated in the 1963 midpoint of James Racial Equality (CORE), Council of Federated Primary Election Freedom Vote. Comedian GREENWOOD AND LEFLORE COUNTY, MISSISSIPPI Meredith’s “March Organizations (COFO), Southern Christian and activist Dick Gregory spoke at the church Against Fear” from Memphis to Jackson. in the spring of that year as part of his cam- Carmichael and two other marchers had paign to provide food and clothing to those been arrested for pitching tents on a school left in need after Leflore County Supervisors Birth of a Movement campus. By the time they were bailed out, discontinued federal commodities distribution. “In the meetings everything--- more than 600 marchers and local people uncertainty, fear, even desperation--- had gathered in the park, and Carmichael St. Francis Center finds expression, and there is comfort seized the moment to voice the “black 709 Avenue I power” slogan, which fellow SNCC worker This Catholic Church structure served as a and sustenance in talkin‘ ‘bout it.” Willie Ricks had originated. hospital for blacks and a food distribution – Michael Thelwell, SNCC Organizer center in the years before the Civil Rights First SNCC Office Movement. -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

February 2014

STATE GAZETTE I SUNDAY FEBRUAFY 2,2014 THE JACKSON SUN . SUNDAY,FEB.2,2014 UTM Ripley Center offers Internet UT Martin mu$Gum basics course The University of Ten- Gommemorates nessee Martin Office of exhibit Extended Campus and Online Studies is sponsor- ing an Internet basics 50th anniYcrsary of course. The course will be offered from 1, to 4 p.m. Thursday at the UT Tennessee sit-ins Martin Ripley Center. Tangelia Fayne-Yar- Special to the State Gazette bough will teach the MARTIN Tenn. - An intimate look at the role course, according-to a Tbnnessee students played in shaping the modern news reiease. The course Civil Rights Movement is explored in "We Shall Not is an opportunity to learn Be Moved: The 50th Anniversary of Tennessee's Civil how to navigate through Rights Sit-Ins" - an exhibit featured at the J. Houston the Internet, create an Gordon Museum at the University of Tennessee at email account, use Inter- Martin. net etiquette in sending fire exhibit, on display from Feb. l-March 14, fea- emails, attach documents tures artifacts, photographic images, and audiovisual to an email message, in- media related to the nonviolent direct-action cam- corporate text in the body of an email, create pargn to end racial segregation at lunch counters in folders for individual downtown Nashville which occurred from Feb. 13 to documents, store impor- May 10, 1960. tant documents for fu- Fifty years ago, a handfirl of Nashville college stu- ture use and delete items dents from Fisk University Tennessee A&I (later that are no longer need- Tennessee State) and American Baptist Theological ed. -

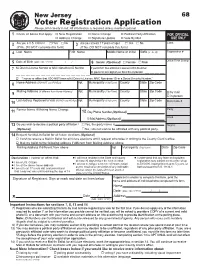

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please Print Clearly in Ink

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please print clearly in ink. All information is required unless marked optional. 1 Check all boxes that apply: o New Registration o Name Change o Political Party Affiliation FOR OFFICIAL o Address Change o Signature Update o Vote By Mail USE ONLY 2 Are you a U.S. Citizen? o Yes o No 3 Are you at least 17 years of age? o Yes o No Clerk (If No, DO NOT complete this form) (If No, DO NOT complete this form) 4 Last Name First Name Middle Name or Initial Suffix (Jr., Sr., III) Registration # Office Time Stamp 5 Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) / / 6 Gender (Optional) o Female o Male 7 NJ Driver’s License Number or MVC Non-driver ID Number If you DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License or MVC Non-Driver ID, provide the last 4 digits of your Social Security Number. __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ o “I swear or affirm that I DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License, MVC Non-driver ID or a Social Security Number.” Home Address (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 8 Mailing Address (If different from Home Address) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code o 9 by mail o in person Last Address Registered to Vote (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 10 Muni Code # Former Name if Making Name Change Party 11 12 Day Phone Number (Optional) Ward E-Mail Address (Optional) 13 Do you wish to declare a political party affiliation? o Yes, the party name is . -

~I~I ~I~ ~I~ Dfa-Aa

Date Printed: 02/05/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 52 Tab Number: 10 Document Title: NATIONAL CIVIC REVIEW: THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT AT THIRTY Document Date: 1995 Document Country: USA Document Language: ENG 1FES 1D: EL00754 ~I~I ~I~ ~I~ * 5 6 DFA-AA * WHEN REFORMED LOCAL GOVERNMENT DOESN'T WORK CINCINNATI CITIZENS DEFEND THE SYSTEM .......-VIEW THE C1 ; CONTENTS ________..... V.. OL,.UM __ E.. 84'''' ... NU... M iiiBE_R4 FALL-WINTER 1995 CHRISTOPHER T. GATES THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT Publisher DAVID LAMPE AT THIRTY Editor EDITORIAL BOARD Long considered the most successful civil rights refonn Itgislation o/the 19605, the Voting Rights Act Jaceson CHARLES K. BENS uncertain future as it enters its fourth decade. The principal Restoring Confidence assault involves challenges to outcome-based enforcement of BARRY CHECKOWAY the Act intended to ensure minority representation in addition Healthy Communities to electoral access. DAVID CHRISLIP Community Leadership PERRY DAVIS SYMPOSIUM Economic Development 287 ELECTION SYSTEMS AND WILLIAM R. DODGE REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY Strategic Planning By Joseph F. Zimmerman LEONARD j. DUHL Healthy Communities An overoiewofthe key prouisionsojthe Act and major amendments (1970, 1975 and 1982), with PAUL D. EPSTEIN discussion of landmark judicial opinions and their Government Performance impact on enforcement. SUZANNE PASS Government Performance 310 TENUOUS INTERPRETATION: JOHN GUNYOU SECTIONS 2 AND 5 OF THE Public Finance VOTING RIGHTS ACT HARRYHATRY By Olethia Davis Innovative Service Delivery A discussion of the general pattern of vacilla ROBERTA MILLER tion on the part of the Supreme Court in its interpre Community Leadership tation of the key enforcement provisions of the Act, CARL M. -

Will the Circle Be Unbroken?" Program Files and Sound Recordings, 1956-1999 (Bulk 1983-1998)

SOUTHERN REGIONAL COUNCIL "Will the Circle Be Unbroken?" program files and sound recordings, 1956-1999 (bulk 1983-1998) Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Southern Regional Council Title: "Will the Circle Be Unbroken?" program files and sound recordings, 1956-1999 (bulk 1983-1998) Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 934 Extent: 35 linear feet (55 boxes) and 82.7 MB born digital material (457 files) Abstract: Program files and sound recordings from the award winning radio documentary, "Will the Circle Be Unbroken?: An Audio History of the Civil Rights Movement in Five Southern Communities and the Music of Those Times," produced by the Southern Regional Council (SRC). The collections consists of interview transcripts, audiovisual materials, born digital materials, scripts, program research files, and production files. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Special restrictions also apply: The collection contains some copies of original materials held by other institutions; these copies may not be reproduced without the permission of the owner of the originals. Use copies have not been made for the audiovisual materials at this time. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance for access to these materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study.