The Truth About Voter Fraud 7 Clerical Or Typographical Errors 7 Bad “Matching” 8 Jumping to Conclusions 9 Voter Mistakes 11 VI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to Robert Duncan

August 24, 2020 Robert M. Duncan Chairman USPS Board of Governors 475 L'Enfant Plaza SW Washington, DC 20260 Mr. Duncan, With an expected onslaught of requests by Americans for mail-in ballots leading up to the 2020 election and repeated attacks by President Trump on the efficacy of voting by mail, it is essential now more than ever that those at the helm of the United States Postal Service (USPS) have the best interests of the American people, and the postal service as an institution, driving their actions. Due to your extensive past involvement in voter disenfranchisement efforts, we call on you to resign from the USPS Board of Governors. Your history raises significant concerns about your commitment to ensuring free, fair, and accessible voting. During your tenure as general counsel of the Republican National Committee and as a member of the Kentucky Republican Party’s executive committee, numerous state parties — including Kentucky’s — were accused of coordinated voter suppression efforts via the banned practice of voter caging1 in an attempt to sway the 2004 election.2 Despite the Republican National Committee being forbidden from conducting voter caging by a court-ordered consent decree in 1982,3 accusations surrounding Kentucky’s 2004 election suggest that you may have overseen this type of voter suppression — primarily in majority- minority metropolitan areas.4 Your role in the potential voter suppression tactic deployed by Kentucky’s Republican Party is particularly suspect given your positions in both the state party and the Republican National Committee, as internal emails suggest the groups were in close coordination to carry out these efforts.5 Your history in Kentucky alone should be reason for grave concern about your ability to protect Americans’ access to voting. -

V Proof of Residence for Voter Registration

v Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration What Do I Need To Know About Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration? A Proof of Residence document is a document that proves where you live in Wisconsin and is only used when registering to vote. Photo ID is separate, you only show photo ID to prove who you are when you request an absentee ballot or receive a ballot at your polling place. When Do I Have To Provide Proof Of Residence? All voters MUST provide a Proof of Residence Document. If you register to vote by mail, in-person in your clerk’s office, with a Election Registration Official, or at your polling place on Election Day, you need to provide a Proof of Residence document. * If you are an active military voter, or a permanent overseas voter (with no intent to return to the U.S.) you do not need to provide a Proof of Residence document. What Documents Can I Use As Proof Of Residence For Registering? All Proof of Residence documents must include the voter’s name and current residential address. • A current and valid State of Wisconsin Driver License or State ID card. • Any other official identification card or license issued by a Wisconsin governmental body or unit. • Any identification card issued by an employer in the normal course of business and bearing a photo of the card holder, but not including a business card. • A real estate tax bill or receipt for the current year or the year preceding the date of the election. • A university, college, or technical college identification card (must include photo) ONLY if the voter provides a fee receipt dated within the last 9 months or the institution provides a certified housing list, that indicates citizenship, to the municipal clerk. -

Local Election Act;

1 AN ACT 2 RELATING TO ELECTIONS; ENACTING THE LOCAL ELECTION ACT; 3 PROVIDING FOR A SINGLE ELECTION DAY AND UNIFORM PROCESSES FOR 4 CERTAIN LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS; PROVIDING THAT CERTAIN 5 BALLOT MEASURE ELECTIONS THAT ARE HELD AT TIMES OTHER THAN 6 WITH REGULAR LOCAL ELECTIONS ONLY BE CONDUCTED BY MAILED 7 BALLOT; REQUIRING SPECIAL STATEWIDE BALLOT QUESTION ELECTIONS 8 TO BE CONDUCTED BY MAILED BALLOT; PROHIBITING ADVISORY 9 QUESTIONS ON THE BALLOT; UPDATING CIRCUMSTANCES CAUSING A 10 VACANCY IN LOCAL OFFICE; NAMING CHAPTER 1, ARTICLE 24 NMSA 11 1978 THE "SPECIAL ELECTION ACT"; CHANGING THE LIMITS ON SOIL 12 AND WATER CONSERVATION LEVIES; REPEALING THE SCHOOL ELECTION 13 LAW, THE MAIL BALLOT ELECTION ACT, THE MUNICIPAL ELECTION 14 CODE AND OTHER PROVISIONS OF LAW IN CONFLICT WITH THE LOCAL 15 ELECTION ACT; MAKING CONFORMING AMENDMENTS TO OTHER SECTIONS 16 OF LAW; MAKING AN APPROPRIATION. 17 18 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF NEW MEXICO: 19 SECTION 1. Section 1-1-19 NMSA 1978 (being Laws 1969, 20 Chapter 240, Section 19, as amended) is amended to read: 21 "1-1-19. ELECTIONS COVERED BY CODE.-- 22 A. The Election Code applies to the following: 23 (1) general elections; 24 (2) primary elections; 25 (3) special elections; HLELC/HB 98 Page 1 1 (4) elections to fill vacancies in the 2 office of United States representative; 3 (5) local elections included in the Local 4 Election Act; and 5 (6) recall elections of county officers, 6 school board members or applicable municipal officers. 7 B. -

Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization

U. S. Department of Justice I Bureau of Justice Statistics I Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization by Herbert Koppel people's perception of the meaning of BJS Analyst March 1987 annual rates with respect to their own The Bureau of Justice Statistics lives. If the Earth revolved around the This report provides estimates of the National Crime Survey provides sun in 180 days, all of our annual crime likelihood that a person will become a annual victimization rates based rates would be halved, but we would not victim of crime during his or her life- on counts of the number of crimes be safer. time, or that a household will be vic- reported and not reported to timized during a 20-year period. This police in the United States. These Calculating lifetime victimization rates contrasts with the conventional use of a rates are based on interviews 1-year period in measuring crime and twice a year with about 101,000 For this report, lifetime likelihoods criminal victimization. Most promi- persons in approximately 49,000 of victimization were calculated from nently, the National Crime Survey nationally representative NCS annual victimization rates and life (NCS) surveys a sample of U.S. house- households. Those annual rates, tables published by the National Center holds and publishes annual victimization while of obvious utility to for Health statistics.% The probability rates, and the FBI's Uniform Crime policymakers, researchers, and that a person will be victimized at a Reports (UCR) provide annual rates of statisticians, do not convey to particular age basically depends upon crimes reported to the police. -

Vultures' Picnic

The wizard of ooze A 24-pAGE EXCERPT FROM VULtures’ Picnic IN PURSUIT OF PETROLEUM PIGS, POWER PIRATES, AND HIGH-FINANCE CARNIVORES BY GREG PALAST ColdType THE BOOK VULTUREs’ PICNIC: In Pursuit of Petroleum Pigs, Power Pirates and High- Finance Predators., is a tale of oil, sex, shoes, radiation and investigative reporting. From the Arctic Circle to the Islamic Republic of BP, from a burnt nuclear reactor in Japan to Mardi Gras in New Orleans, Palast uncovers a story you won’t get on CNN. Greg Palast’s crew of journalist-detectives chase down British Petroleum bag men, CIA operatives, nuclear power con men – and “The Vultures,” billionaire financial speculators who, through bribery, flim-flam and political muscle, take entire nations hostage for mega-profits. ISBN: 978-0-525-95207-7 THE AUTHOR Greg Palast is best known as the investigative reported who uncovered how Katherine Harris purged thousands of African-Americans from Florida oters rolls in the 2000 Presidential Election. He is author of the international bestsellers, The Best Democracy Money Can Buy and Armed Madhouse This excerpt is Chapter Six of Vultures’ Picnic, and is republished with permission of the author Published by Dutton, Price: $26.95 ($16.89 at Amazon.com) ColdType WRITING WORTH READING FROM AROUND THE WORLD www.coldtype.net CHAPTER 6 The Wizard of Ooze HELSINKI STATION Jack Grynberg said, How did you fi nd me? I looked under G. The old spook was a hunter, not used to being hunted. I’m not Sam Spade: Grynberg only gets found when he wants to be found. -

Elections--Equal Protection [Williams V

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 20 Issue 4 Article 10 1969 Recent Decisions: Constitutional Law--Elections--Equal Protection [Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968)] E. E. E. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation E. E. E., Recent Decisions: Constitutional Law--Elections--Equal Protection [Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968)], 20 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 892 (1969) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol20/iss4/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CASE WESTERN RESERVE LAW REVIEW [Vol. 20:892 CONSTITUTIONAL LAW - ELECTIONS - EQUAL PROTECTION Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968). While traditionally two political parties have dominated Amer- ican Presidential elections, there has frequently been a third-party candidate who, although never successful, has often provided color and dignity to an otherwise overbearing ritual. A primary reason for an independent party's lack of success has been its inability to comply with the rigid requirements of diverse state election laws. Usually, state statutes permit voters to write in a party or candidate's name only if that party or candidate has fulfilled certain conditions; moreover, in order to secure a printed position on the ballot, the same party or candidate must comply with more rigid statutory requirements. -

Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization

.,. u.s, Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics Lifetime Likelihood of Victimization by Het'bert Koppel people's perception of the meaning of BJS Analyst Mat'ch 1987 annual ra tes with respect to their own The Bureau of Justice Statistics lives. If the Earth revolved around the This report provides estimates of the National Crime Survey provides sun in 180 days, all of our annual crime likelihood that a person will become a annual victimization rates based rates would be halved, but we would not victim of crime during his or her life on counts of the number of crimes be safer. time, or that a household will be vic reported and not reported to timized during a 20-year pel'iod. This police in the United States. These Calculating lifetime victimization fates contrasts with the conventional use of a rates are based on interviews I-year period in measuring crime and twice a year with about lOl,OOO For this report, lifetime likelihoods criminal victimization. Most promi persons in approximately 49,000 of victimization were calculated from nently, the National Crime Survey na tionally representative NCS annual victimi.zation rates and life (NCS) surveys a sample of U.S. house households. Those annual ra ces, tables published by the National Center 2 holds and publishes annual victimization while of obvious utility to for Health Statistics. The probability rates, and the FBI's Uniform Crime policymakel's, researchers, and that a person will be victimized at a Reports (UCR) provide annual rates of statisticians, do not convey to particular age basically depends upon crimes reported to the police. -

Appropriations Committee

1 APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency Presented by Joseph L. LaFleur, Director Pennsylvania Lottery Presented by Secretary Rhodes Secretary of Revenue Eileen McNulty Stenographic transcript of meeting held the Finance Building and Hearing Room 140, the Main Capitol, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Wednesday March 10, 1993 At 10:10 o'clock a.m. EMBERS OF THE APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE: DWIGHT EVANS, Chairman GORDON LINTON, Vice Chairman RICHARD KASUNIC, Subc. Chairman of Capitol Budget JOSEPH BATTISTO, Subc. Chairman on Education BABETTE JOSEPHS, Subc. Chairman on Health/Welfare LEO TRICH, Secretary JOSEPH PITTS, Minority Chairman ALVIN C. BUSH, Min. Subc. Chairman, Capitol Budget PATRICK FLEAGLE, Min. Subc. Chairman on Education DAVID G. ARGALL, Min. Subc. Chairman, Health/Welfare HOLBERT ASSOCIATES DEBRA ROSE-KEENAN 2611 Doehne Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17110 HOLBERT ASSOCIATES \ r (717) 540-9669 \ 2 LAJORITY MEMBERS REPRESENTATIVE ANDREW CARN REPRESENTATIVE ANTHONY DELUCA REPRESENTATIVE MICHAEL GRUITZA REPRESENTATIVE EDWARD HALUSKA REPRESENTATIVE STANLEY JAROLIN REPRESENTATIVE FRANK LAGROTTA REPRESENTATIVE KEITH MCCALL REPRESENTATIVE KEITH MCCALL REPRESENTATIVE RICHARD OLASZ REPRESENTATIVE JOSEPH PRESTON REPRESENTATIVE WILLIAM ROBINSON REPRESENTATIVE EDWARD STABACK REPRESENTATIVE STEPHEN STETLER REPRESENTATIVE THOMAS TANGRETTI REPRESENTATIVE JOHN WOZNIAK MINORITY MEMBERS REPRESENTATIVE WILLIAM ADOLPH, JR. REPRESENTATIVE THERESA E. BROWN REPRESENTATIVE RAYMOND BUNT, JR. REPRESENTATIVE ELAINE FARMER REPRESENTATIVE ROBERT J. FLICK REPRESENTATIVE GEORGE T. KENNEY, JR. REPRESENTATIVE JERE W. SCHULER REPRESENTATIVE PAUL SEMMEL HOLBERT ASSOCIATES (717) 540-9669 3 CONTENTS iUEST SPEAKER PRESENTATION Foseph L. LaFleur 4 iecretary Rhodes 52 iecretary McNulty 52 HOLBERT ASSOCIATES (717) 540-9669 4 CHAIRMAN EVANS: What I would like to do is reconvene the House Appropriations Committee meeting from ;he tour that was excellent this morning, in a sense. -

Chapter 4: State Regulation of Ballot Measures

CHAPTER 4: STATE REGULATION OF BALLOT MEASURES I. Introduction A. Nature of Ballot Measures B. Types of Ballot Measures C. State Regulation of Ballot Measures II. State Regulation of Ballot Measure Ballot Access A. Presentation of Intent B. Measure Approved/Title Assigned/Petition Created C. Petition Circulation 1. Circulator Requirements 2. Signature Requirements a. Numerical Requirements b. Geographic Distribution Requirements c. Restrictions on Who May Sign the Petition 3. Witness/Attestation Requirements D. Certification for Ballot Access E. Required Ballot Information III. Court Involvement in Ballot Measure Issues A. Procedural Challenges B. Substantive Challenges 1. Single Issue 2. Constitutional Amendment vs. Revision 3. Measure Exceeds Legislative Authority 4. Constitutionality I. INTRODUCTION A. NATURE OF BALLOT MEASURES Many, but not all,1 states recognize a citizen’s right to place measures on the ballot by one or more of the processes known as initiative,2 referendum, and recall. In some states, these exercises in direct democracy are a reserved power of the people recognized by the state constitution, while in others the ability to propose ballot measures exists only through a legislative grant of authority.3 1 See INITIATIVE & REFERENDUM INSTITUTE, http://www.iandrinstitute.org/statewide_i&r.htm (last visited July 28, 2007) (listing state-by-state information on the initiative and referendum processes available). 2 An initiative is a voter-proposed statute or constitutional amendment that is placed on the ballot by petition. Citizens use initiatives to bypass their governmental representatives and enact change directly. 3 See, e.g., Hoyle v. Priest, 59 F. Supp. 2d 827, 835 (W.D. -

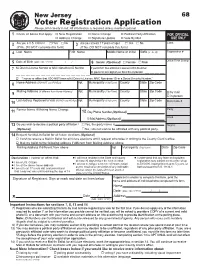

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please Print Clearly in Ink

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please print clearly in ink. All information is required unless marked optional. 1 Check all boxes that apply: o New Registration o Name Change o Political Party Affiliation FOR OFFICIAL o Address Change o Signature Update o Vote By Mail USE ONLY 2 Are you a U.S. Citizen? o Yes o No 3 Are you at least 17 years of age? o Yes o No Clerk (If No, DO NOT complete this form) (If No, DO NOT complete this form) 4 Last Name First Name Middle Name or Initial Suffix (Jr., Sr., III) Registration # Office Time Stamp 5 Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) / / 6 Gender (Optional) o Female o Male 7 NJ Driver’s License Number or MVC Non-driver ID Number If you DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License or MVC Non-Driver ID, provide the last 4 digits of your Social Security Number. __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ o “I swear or affirm that I DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License, MVC Non-driver ID or a Social Security Number.” Home Address (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 8 Mailing Address (If different from Home Address) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code o 9 by mail o in person Last Address Registered to Vote (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 10 Muni Code # Former Name if Making Name Change Party 11 12 Day Phone Number (Optional) Ward E-Mail Address (Optional) 13 Do you wish to declare a political party affiliation? o Yes, the party name is . -

The Donor Class: Campaign Finance, Democracy, and Participation

THE DONOR CLASS: CAMPAIGN FINANCE, DEMOCRACY, AND PARTICIPATION † SPENCER OVERTON As a result of disparities in resources, a small, wealthy, and homogenous donor class makes large contributions that fund the bulk of American politics. Even in the aftermath of recent campaign reforms, the donor class effectively de- termines which candidates possess the resources to run viable campaigns. This reality undermines the democratic value of widespread participation. Instead of preventing “corruption” or equalizing funds between candidates, the primary goal of campaign reform should be to reduce the impact of wealth disparities and empower more citizens to participate in the funding of campaigns. On av- erage, candidates should receive a larger percentage of their funds from a greater number of people in smaller contribution amounts. Reforms such as es- tablishing matching funds and providing tax credits for smaller contributions, combined with emerging technology, would enable more Americans to make con- tributions and would enhance their voices in our democracy. INTRODUCTION Opponents of campaign finance reform embrace a relatively lais- sez-faire reliance on private markets to fund campaigns for public of- fice. Although they champion the individual rights of those who con- † Associate Professor of Law, The George Washington University Law School. Mi- chael Abramowicz, Mark Alexander, Brandon Briscoe, Kim Christensen, Richard Ha- sen, Adam Lioz, Ira Lupu, Leslie Overton, Josiah Slotnick, Dan Solove, and Fane Wolfer read earlier drafts of this -

Twitter and Millennial Participation in Voting During Nigeria's 2015 Presidential Elections

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2021 Twitter and Millennial Participation in Voting During Nigeria's 2015 Presidential Elections Deborah Zoaka Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Deborah Zoaka has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Lisa Saye, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Raj Singh, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Christopher Jones, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer and Provost Sue Subocz, Ph.D. Walden University 2021 Abstract Twitter and Millennial Participation in Voting during Nigeria’s 2015 Presidential Elections by Deborah Zoaka MPA Walden University, 2013 B.Sc. Maiduguri University, 1989 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University May, 2021 Abstract This qualitative phenomenological research explored the significance of Twitter in Nigeria’s media ecology within the context of its capabilities to influence the millennial generation to participate in voting during the 2015 presidential election. Millennial participation in voting has been abysmally low since 1999, when democratic governance was restored in Nigeria after 26 years of military rule, constituting a grave threat to democratic consolidation and electoral legitimacy. The study was sited within the theoretical framework of Democratic participant theory and the uses and gratifications theory.