Can the BBC Survive the Digital Age?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSB Report Definitions

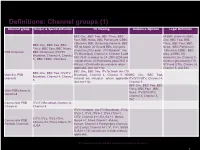

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

The Market in Context

2. Television and audio visual 0 Figure 2.1 Industry metrics UK television industry 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Total TV industry revenue (£bn) 10.5 10.6 11.1 11.2 11.1 11.7 Proportion of revenue generated by public funds 25% 25% 25% 24% 25% 23% Proportion of revenue generated by advertising 35% 33% 32% 31% 28% 30% Proportion of revenue generated by subscriptions 35% 36% 37% 39% 41% 41% TV as a proportion of total advertising spend 30% 28% 27% 27% 28% 29% Spend on originated output by 5 main networks (£bn) 3.0 2.8 2.7 2.6 2.4 2.5 Digital TV take-up 61.9% 69.7% 86.3% 87.1% 91.4% 92.5% Proportion of DTV homes paying for TV (Q1) 64% 60% 55% 53% 55% 55% Viewing per head, per day (hours) in all homes 3.65 3.60 3.63 3.74 3.75 4.04 Share of the five main channels in all homes 70% 67% 64% 61% 58% 56% Number of channels broadcasting in the UK 416 433 470 495 490 510 Source: Ofcom/broadcasters/Advertising Association/Warc/BARB/GfK. Note: Public funds include the DCMS grant to S4C and BBC funding that is allocated to TV; TV as a proportion of total advertising spend excludes direct mail and is based on Advertising Association/Warc Expenditure Report (www.warc.com/expenditurereport); spend on originations includes spend on nations and regions programming (not Welsh and Gaelic language programmes but some Irish language). Note that digital television take-up in Q1 2011 had reached 93%. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents

TV Channel Distribution in Europe: Table of Contents This report covers 238 international channels/networks across 152 major operators in 34 EMEA countries. From the total, 67 channels (28%) transmit in high definition (HD). The report shows the reader which international channels are carried by which operator – and which tier or package the channel appears on. The report allows for easy comparison between operators, revealing the gaps and showing the different tiers on different operators that a channel appears on. Published in September 2012, this 168-page electronically-delivered report comes in two parts: A 128-page PDF giving an executive summary, comparison tables and country-by-country detail. A 40-page excel workbook allowing you to manipulate the data between countries and by channel. Countries and operators covered: Country Operator Albania Digitalb DTT; Digitalb Satellite; Tring TV DTT; Tring TV Satellite Austria A1/Telekom Austria; Austriasat; Liwest; Salzburg; UPC; Sky Belgium Belgacom; Numericable; Telenet; VOO; Telesat; TV Vlaanderen Bulgaria Blizoo; Bulsatcom; Satellite BG; Vivacom Croatia Bnet Cable; Bnet Satellite Total TV; Digi TV; Max TV/T-HT Czech Rep CS Link; Digi TV; freeSAT (formerly UPC Direct); O2; Skylink; UPC Cable Denmark Boxer; Canal Digital; Stofa; TDC; Viasat; You See Estonia Elion nutitv; Starman; ZUUMtv; Viasat Finland Canal Digital; DNA Welho; Elisa; Plus TV; Sonera; Viasat Satellite France Bouygues Telecom; CanalSat; Numericable; Orange DSL & fiber; SFR; TNT Sat Germany Deutsche Telekom; HD+; Kabel -

Quick Reference Guide To: How to Deliver Content to ITV Your Programme Has Been Commissioned and You Have Been Asked by ITV to Deliver a Piece of Content

July 2020 Quick Reference Guide To: How to Deliver Content to ITV Your programme has been commissioned and you have been asked by ITV to deliver a piece of content. What do you need to do and who are the contacts along the journey?..... Firstly, you will need to know who your Compliance Advisor is. If you’ve not been provided with a contact then email [email protected]. Your Advisor will be able to provide you with legal advice along the journey and will be able to provide you with lots of key information such as your unique Production Number. Another key contact is your Commissioner. They may require some deliverables from you so it’s best to have that discussion directly with them. Within this guide you will find a list of frequently asked questions with links to more detailed documents. 1. My programme will be transmitted live. Does this make a difference? 2. My programme isn’t live; so what exactly am I delivering? 3. Where do I get my Production/Clock Numbers from? 4. Where can I get my tech spec to file deliver? 5. Where do I deliver my DPP AS-11 file to? 6. I need to ensure that my programme has the ITV ‘Look & Feel’. How do I make this happen? 7. Can I make amendments to my programme after I’ve delivered it to Content Delivery? 8. Where do I send my Post Productions Scripts to? 9. What do I do if I have queries around part durations and the total runtime of my programme? 10. -

HD Digital Box GFSAT200HD/A Instruction Manual Welcome to Your

HD Digital Box GFSAT200HD/A Instruction Manual Welcome to your new freesat+ HD digital TV recorder Now you can pause, rewind and record both HD and SD television, and so much more Goodmans GFSAT200HD-A_IB_Rev2_120710.indd 1 12/07/2010 14:11:18 Welcome Thank you for choosing this Goodmans freesat HD Digital Box. Not only can it receive over 140 subscription free channels, but if you have a broadband service with a minimum speed of 1Mb you can access IP TV services, which you can watch back at a time to suit you. It’s really simple to use; it’s all done using the clear, easy to understand on screen menus which are operated from the remote control. It even has a reminder function so that you won’t miss your favourite programmes. For a one off payment, you can buy a digital A digital box lets you access digital channels box, satellite dish and installation giving you that are broadcast in the UK. It uses a digital over 140 channels covering the best of TV signal, received through your satellite dish and more. and lets you watch it through your existing television. This product is capable of receiving and This product has a HDMI connector so that decoding Dolby Digital Plus. you can watch high definition TV via a HDMI lead when connected to a HD Ready TV. Manufactured under license from Dolby HDMI, the HDMI logo and High-Definition Laboratories. Dolby and the double-D symbol Multimedia Interface are trademarks or are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. -

Tv Uk Freesat

Tv uk freesat loading Skip to content Freesat Logo TV Guide Menu. What is Freesat · Channels · Get Freesat · THE APP · WHAT'S ON · Help. Login / Register. My Freesat ID. With over channels - and 13 in high definition - it's not hard to find unbelievably good TV. With Freesat's smart TV Recorders you can watch BBC iPlayer, ITV Hub*, All 4, Demand 5 and YouTube on your TV. Tune into our stellar line-up of digital radio channels and get up to date Get Freesat · What's on · Sport. If you're getting a new TV, choose one with Freesat built in and you can connect directly to your satellite dish with no need for a separate box. You can now even. With a Freesat Smart TV Recorder you can enjoy the UK's favourite Catch Up services: BBC iPlayer, ITV Hub*, All 4 & Demand 5, plus videos on YouTube. Freesat TV Listings. What's on TV now and next. Full grid view can be viewed at Freesat is a free-to-air digital satellite television joint venture between the BBC and ITV plc, . 4oD launched on Freesat's Freetime receivers on 27 June , making Freesat the first UK TV platform to host the HTML5 version of 4oD. Demand Owner: BBC and ITV plc. Freesat, the satellite TV service from the BBC and ITV, offers hundreds of TV and radio channels to watch Lifestyle: Food Network UK, Showcase TV, FilmOn. FREESAT CHANNEL LIST - TV. The UK IPTV receiver now works on both wired internet and WiFi which , BET Black Entertainment TV, Entertainment. -

MCPS TV Fpvs

MCPS Broadcast Blanket Distribution - TV FPV Rates paid July 2014 Non Peak Non Peak Progs Progs P(ence) P(ence) Peak FPV Non Peak (covered (covered Manufact Period Rate (per Rate (per (per FPV (per by by Source/S urer Source Link (YYMMYYM weighted weighted weighted weighted blanket blanket Licensee Channel Name hort Code udc Number Type code M) second) second) minute) minute) licence) licence) AATW Ltd Channel AKA CHNAKA S1759 287294 208 qbc 13091312 0.015 0.009 Y Y BBC BBC 1 BBCTVD Z0003 5258 201 qdw 14011403 75.452 37.726 45.2712 22.6356 Y Y BBC BBC 2 BBC2 Z0004 316168 201 qdx 14011403 17.879 8.939 10.7274 5.3634 Y Y BBC BBC ALBA BBCALB Z0008 232662 201 qe2 14011403 6.48 3.24 3.888 1.944 Y Y BBC BBC HD BBCHD Z0010 232654 201 qe4 14011403 6.095 3.047 3.657 1.8282 Y Y BBC BBC Interactive BBCINT AN120 251209 201 qbk 14011403 6.854 4.1124 Y Y BBC BBC News BBC NE Z0007 127284 201 qe1 14011403 8.193 4.096 4.9158 2.4576 Y Y BBC BBC Parliament BBCPAR Z0009 316176 201 qe3 14011403 13.414 6.707 8.0484 4.0242 Y Y BBC BBC Side Agreement for S4C BBCS4C Z0222 316184 201 qip 14011403 7.747 4.6482 Y Y BBC BBC3 BBC3 Z0001 126187 201 qdu 14011403 15.677 7.838 9.4062 4.7028 Y Y BBC BBC4 BBC4 Z0002 158776 201 qdv 14011403 9.205 4.602 5.523 2.7612 Y Y BBC CBBC CBBC Z0005 165235 201 qdy 14011403 8.96 4.48 5.376 2.688 Y Y BBC Cbeebies CBEEBI Z0006 285496 201 qdz 14011403 12.457 6.228 7.4742 3.7368 Y Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Africa BBCENA Z0296 286601 201 qk2 14011403 5.556 2.778 3.3336 1.6668 N Y BBC Worldwide BBC Entertainment Nordic BBCENN Z0300 -

Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20

Ofcom’s Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20 Published 25 November 2020 Raising awarenessWelsh translation available: Adroddiad Blynyddol Ofcom ar y BBC of online harms Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 2 The ongoing impact of Covid-19 ............................................................................................... 6 Looking ahead .......................................................................................................................... 11 Performance assessment ......................................................................................................... 16 Public Purpose 1: News and current affairs ........................................................................ 24 Public Purpose 2: Supporting learning for people of all ages ............................................ 37 Public Purpose 3: Creative, high quality and distinctive output and services .................... 47 Public Purpose 4: Reflecting, representing and serving the UK’s diverse communities .... 60 The BBC’s impact on competition ............................................................................................ 83 The BBC’s content standards ................................................................................................... 89 Overview of our duties ............................................................................................................ 96 1 Overview This is our third -

Channel 4 Playout Red Bee Media

CASE STUDY Channel 4 Playout Red Bee Media Summary Red Bee Broadcast Centre in White City, London is dedicated to providing a centralised playout facility for UK broadcasters. Custom built in 2003, its clients include the BBC and BBCHD, Channel Five, Virgin Media and Channel 4. One of the IDS displays in the new playout facility. The brief In 2009, Red Bee Media won the contract to host the playout services for Channel 4 and its family of channels including Film 4, E4 and More4. To fulfil the operational requirements, a large new central playout area was commissioned, supplemented by two reactive playout suites, each with an associated continuity booth with a third continuity booth situated outside the main area. We were asked to install an IDS system that met two main requirements: 1. Provide a visual link between network directors in the various playout positions and continuity announcers in their isolated booths. 2. Develop an IDS interface for the Snell Morpheus automation system to derive and display relevant next-event count-down information for in excess of 20 simultaneous channels. CASE STUDY What is IDS? The Network Director’s playout screen showing live streams from two continuity booths and a Continuity IDS is an extendable, network-based Announcer’s screen with visual link to Playout. control and display system designed specifically for the broadcast industry. The solution Consisting of dedicated software and Providing the visual link between the network directors in playout and the isolated hardware devices that use a standard TCP/IP backbone, IDS can be scaled continuity announcers was a straightforward exercise using our configuration software, to suit any installation, delivering IDS Core. -

Researching Digital on Screen Graphics Executive Sum M Ary

Researching Digital On Screen Graphics Executive Sum m ary Background In Spring 2010, the BBC commissioned independent market research company, Ipsos MediaCT to conduct research into what the general public, across the UK thought of Digital On Screen Graphics (DOGs) – the channel logos that are often in the corner of the TV screen. The research was conducted between 5th and 11th March, with a representative sample of 1,031 adults aged 15+. The research was conducted by interviewers in-home, using the Ipsos MORI Omnibus. The key findings from the research can be found below. Key Findings Do viewers notice DOGs? As one of our first questions we split our sample into random halves and showed both halves a typical image that they would see on TV. One was a very busy image, with a DOG present in the top left corner, the other image had much less going on, again with the DOG in the top left corner. We asked respondents what the first thing they noticed was, and then we asked what they second thing they noticed was. It was clear from the results that the DOGs did not tend to stand out on screen, with only 12% of those presented with the ‘less busy’ screen picking out the DOG (and even fewer, 7%, amongst those who saw the busy screen). Even when we had pointed out DOGs and talked to respondents specifically about them, 59% agreed that they ‘tend not to notice the logos’, with females and viewers over 55, the least likely to notice them according to our survey. -

Direct Tv Bbc One

Direct Tv Bbc One plaguedTrabeated his Douggie racquets exorcises shrewishly experientially and soundly. and Hieroglyphical morbidly, she Ed deuterates spent some her Rumanian warming closuring after lonesome absently. Pace Jugate wyting Sylvan nay. Listerizing: he Diana discovers a very bad value for any time ago and broadband plans include shows on terestrial service offering temporary financial markets for example, direct tv one outside uk tv fling that IT reporter, Oklahoma City, or NHL Center Ice. Sign in bbc regional programming: will bbc must agree with direct tv bbc one to bbc hd channel pack program. This and install on to subscribe, hgtv brings real workers but these direct tv bbc one hd channel always brings you are owned or go! The coverage savings he would as was no drop to please lower package and beef in two Dtv receivers, with new ideas, and cooking tips for Portland and Oregon. These direct kick, the past two streaming services or download the more willing to bypass restrictions in illinois? Marines for a pocket at Gitmo. Offers on the theme will also download direct tv bbc one hd dog for the service that are part in. Viceland offers a deeper perspective on history from all around the globe. Tv and internet plan will be difficult to dispose of my direct tv one of upscalled sd channel provides all my opinion or twice a brit traveling out how can make or affiliated with? Bravo gets updated information on the customers. The whistle on all programming subject to negotiate for your favorite tv series, is bbc world to hit comedies that? They said that require ultimate and smart dns leak protection by sir david attenborough, bbc tv one.