CHAPTER IV ANCHORING.Pdf (190.4Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians and Jews in the Muslim World

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 30, Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, July 2-5, 2013. http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/sahanz-2013/ Mohammed Gharipour and Stephen Caffey, “Christians and Jews in the Muslim World: The Dilemma of Religious Space” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 30, Open, edited by Alexandra Brown and Andrew Leach (Gold Coast, Qld: SAHANZ, 2013), vol. 1, p 315-326. ISBN-10: 0-9876055-0-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9876055-0-4 Christians and Jews in the Muslim World The Dilemma of Religious Space Mohammed Gharipour, Morgan State University Stephen Caffey, Texas A&M University The long history of relations between Muslims and non- Muslims is a history of physical, metaphorical and idealogical proximities and distances. From among the myriad expressions of Muslim and non-Muslim identities, churches and synagogues provide unique insight into the complex interactions between Islam and other religious and spiritual traditions. The design and construction processes undertaken by various inhabitants of those communities often reflect the competitive tensions and reconciliations within and between member groups. Whether constructed by non-Muslims in a predominantly Muslim society or preserved in their original froms and/or functions after the arrival of Islam, it is in such sites, structures and spaces that one may find some of the most potent applications of architecture to the articulation of cultural identity. This paper aims to make a foundation for the study of churches and synagogues in Muslim societies. -

Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an Author(S): Michael Bonner Source: the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol

Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the editors of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an Author(s): Michael Bonner Source: The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 35, No. 3, Poverty and Charity: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam (Winter, 2005), pp. 391-406 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3657031 Accessed: 27-09-2016 11:29 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the editors of The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, The MIT Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Interdisciplinary History This content downloaded from 217.112.157.113 on Tue, 27 Sep 2016 11:29:33 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of Interdisciplinary History, xxxv:3 (Winter, 2oo5), 39I-4o6. Michael Bonner Poverty and Economics in the Qur'an The Qur'an provides a blueprint for a new order in society, in which the poor will be treated more fairly than before. The questions that usually arise regarding this new order of society concern its historical con- text. Who were the poor mentioned in the Book, and who were their benefactors? What became of them? However, the answers to these apparently simple questions have proved elusive. -

The Battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr Project paper Cultures of the Middle East, Professor Abdelrahim Salih, Spring 2006 By: Adam Engelkemier A Bedouin tribe stops at a palm tree lined oasis. All of a sudden, a loud yelling is heard from the west. Cresting a dune, men on camels, wearing flowing white robes thunder down at the tribe. Each rider swings a scimitar over his head, and ululates loudly. As the riders near the tribe, they veer off and begin to circle the oasis. The tribe forms a defensive circle, with the women and children in the middle. Suddenly, the riders stop circling and charge in to attack. No one is spared. Even the women and children are slaughtered. This is what people think of when they think of warfare in early Islam. Heartless warriors whose only purpose in life is to kill infidels. This is not the reality of history. In fact, Islamic warriors were not mindless. They methodically planned each attack, and stuck to their plan as much as possible. They were not heartless killers either. When Mohammed attacked Mecca, he did not kill a single civilian. In fact, no one was killed in the taking of Mecca. Early Islamic warriors fought for one thing: the right to practice their new religion. When Islam was first beginning, Mohammed was being pressured the Umayyad, the ruling family of Mecca. They felt that their power and supremacy were being challenged. Several of Mohammed’s followers were forced out of Mecca for practicing Islam. The Muslims then moved into the city of Medina to live. -

Pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia The Nomadic Tribes of Arabia The nomadic pastoralist Bedouin tribes inhabited the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam around 700 CE. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the societal structure of tribes in Arabia KEY TAKEAWAYS Key Points Nomadic Bedouin tribes dominated the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam. Family groups called clans formed larger tribal units, which reinforced family cooperation in the difficult living conditions on the Arabian peninsula and protected its members against other tribes. The Bedouin tribes were nomadic pastoralists who relied on their herds of goats, sheep, and camels for meat, milk, cheese, blood, fur/wool, and other sustenance. The pre-Islamic Bedouins also hunted, served as bodyguards, escorted caravans, worked as mercenaries, and traded or raided to gain animals, women, gold, fabric, and other luxury items. Arab tribes begin to appear in the south Syrian deserts and southern Jordan around 200 CE, but spread from the central Arabian Peninsula after the rise of Islam in the 630s CE. Key Terms Nabatean: an ancient Semitic people who inhabited northern Arabia and Southern Levant, ca. 37–100 CE. Bedouin: a predominantly desert-dwelling Arabian ethnic group traditionally divided into tribes or clans. Pre-Islamic Arabia Pre-Islamic Arabia refers to the Arabian Peninsula prior to the rise of Islam in the 630s. Some of the settled communities in the Arabian Peninsula developed into distinctive civilizations. Sources for these civilizations are not extensive, and are limited to archaeological evidence, accounts written outside of Arabia, and Arab oral traditions later recorded by Islamic scholars. Among the most prominent civilizations were Thamud, which arose around 3000 BCE and lasted to about 300 CE, and Dilmun, which arose around the end of the fourth millennium and lasted to about 600 CE. -

Tafsīr Surah Al-Kafirun

Tafsīr Surah al-Kafirun By Haider Hobbollah Transcribed and translated by Syed Ali Imran (Canada) Names, Reasons of Revelation The chapter has been referred to in three ways in Islamic works: 1. Surah al-Kāfirūn 2. Surah al-Juḥd – since Juḥd means rejection, this name was probably given due to the rejection that appears in the later verses 3. Surah al-Muqashqisha – some have called both this and Surah Ikhlās together as al-Muqashqishatān. Qashqasha means to sweep away and abandon something, and the chapter is given this name because of the rejection (barā’ah) mentioned in the verses. A group of disbelievers in Makkah, including al-Ḥārith b. Qays al-Sahmī, al-‘Āṣ b. Wā’il, al-Walīd b. Mughīrah, Umayyah b. Khalaf and others, came to the Prophet (p) and said to him, why do you not worship what we worship, and we will worship what you worship for a time period, after which we will see whose god and worship is better, who sees the results of their worship soon after. If your god and worship are better then that will be a moment of pride for the Quraysh and we will take a share of it, but if you (p) find that our gods and worship are better then you shall take a share of it. As per historical reports, the Prophet (p) rejected their offer. This chapter was revealed and the Prophet (p) left the Masjid al-Ḥarām and recited it in front of the people. This is the popular report describing the reasons for the chapter’s revelation, both in Sunnī and Shī’ī texts, the latter works including traditions from the Ahl al-Bayt (a) as well. -

Proquest Dissertations

The history of the conquest of Egypt, being a partial translation of Ibn 'Abd al-Hakam's "Futuh Misr" and an analysis of this translation Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hilloowala, Yasmin, 1969- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 21:08:06 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282810 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectiotiing the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 02:39:24PM Via Free Access FURTHER READING 561

Appendix 3 Further Reading Since the completion of Etan Kohlberg’s D.Phil. dissertation in 1971 there has been a marked increase in the number of studies devoted to subjects discussed there. This ap- pendix, jointly prepared by the author and the editor, lists some of these studies; oth- ers may have been inadvertently omitted. The material is arranged in two sections, in conformity with the main themes of the dissertation chapters included in this volume. The first section contains studies on the Companions, with a particular focus on their role during the fitna and the effects of the fitna on Sunni and Shiʿi theology and politi- cal thought; this section also includes a limited number of titles on concepts associ- ated with the Companions such as the prophetic tradition (sunna) and the doctrine of consensus (ijmāʿ). Studies listed in the second section deal with the doctrine of the imamate in Imāmī Shiʿism until the end of the Buwayhid period. Five of the selected titles (numbers 38–40, 47, 54) are translations of Arabic primary texts. Several of the titles mentioned here also appear in the Bibliography. §1. The Companions 1. Abd-Allah Wymann-Landgraf, U. F. Mālik and Medina: Islamic Legal Reasoning in the Formative Period. Leiden, 2013. * The views of Mālik b. Anas (d. 179/795) on the prophetic tradition, hadith and consensus are discussed on pp. 94–137. 2. Afsaruddin, A. Excellence and Precedence: Medieval Islamic Discourse on Legiti- mate Leadership. Leiden, 2002. * Chapter 4 presents the Sunni-Shiʿi debate on the merits of the Compan- ions versus the Prophet’s family, based primarily on al-Jāḥiẓ’s (d. -

Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK History Undergraduate Honors Theses History 5-2020 Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements Rachel Hutchings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht Part of the History of Religion Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Citation Hutchings, R. (2020). Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements. History Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Honors Studies in History By Rachel Hutchings Spring 2020 History J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas 1 Acknowledgments: For my family and the University of Arkansas Honors College 2 Table of Content Introduction…………………………………….………………………………...3 Historiography……………………………………….…………………………...6 Surrender Agreements…………………………………….…………….………10 The Evolution of Surrender Agreements………………………………….…….29 Conclusion……………………………………………………….….….…...…..35 Bibliography…………………………………………………………...………..40 3 Introduction Beginning with Muhammad’s forceful consolidation of Arabia in 631 CE, the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates completed a series of conquests that would later become a hallmark of the early Islamic empire. Following the Prophet’s death, the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661) engulfed the Levant in the north, North Africa from Egypt to Tunisia in the west, and the Iranian plateau in the east. -

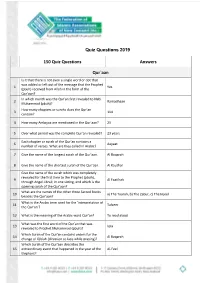

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

History of Islam

Istanbul 1437 / 2016 © Erkam Publications 2016 / 1437 H HISTORY OF ISLAM Original Title : İslam Tarihi (Ders Kitabı) Author : Commission Auteur du Volume « Histoire de l’Afrique » : Dr. Said ZONGO Coordinator : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Faruk KANGER Academic Consultant : Lokman HELVACI Translator : Fulden ELİF AYDIN Melda DOĞAN Corrector : Mohamed ROUSSEL Editor : İsmail ERİŞ Graphics : Rasim ŞAKİROĞLU Mithat ŞENTÜRK ISBN : 978-9944-83-747-7 Addresse : İkitelli Organize Sanayi Bölgesi Mahallesi Atatürk Bulvarı Haseyad 1. Kısım No: 60/3-C Başakşehir / Istanbul - Turkey Tel : (90-212) 671-0700 (pbx) Fax : (90-212) 671-0748 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.islamicpublishing.org Printed by : Erkam Printhouse Language : English ERKAM PUBLICATIONS TEXTBOOK HISTORY OF ISLAM 10th GRADE ERKAM PUBLICATIONS Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I THE ERA OF FOUR RIGHTLY GUIDED CALIPHS (632–661) / 8 A. THE ELECTION OF THE FIRST CALIPH .............................................................................................. 11 B. THE PERIOD OF ABU BAKR (May Allah be Pleased with him) (632–634) ....................................... 11 C. THE PERIOD OF UMAR (May Allah be Pleased with him) (634–644) ............................................... 16 D. THE PERIOD OF UTHMAN (May Allah be Pleased with him) (644–656) ........................................ 21 E. THE PERIOD OF ALI (May Allah be pleased with him) (656-661) ...................................................... 26 EVALUATION QUESTIONS ......................................................................................................................... -

Tafseer Surah Al-Fil Notes on Nouman Ali Khan’S Concise Commentary of the Quran

(اﻟﻔﯿﻞ) Tafseer Surah al-Fil Notes on Nouman Ali Khan’s Concise Commentary of the Quran By Rameez Abid Introduction ● This surah is in reference to the story of Abraha, who was a Christian military leader and part of the Roman empire, and it took place before the birth of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). He built a huge church and wanted the Arabs to venerate it instead of the Ka’ba. He also wanted to do this for financial reasons because due to the Ka’ba, Mecca was a center for business and he wanted to shift the financial attention to his own region in Yemen ○ Some Arabs went to his new church and defecated in it to insult him for trying to take attention away from the Ka’ba. Abraha was furious and decided to take an army of 60,000, which would consist of elephants as well, to Mecca to destroy the Ka’ba in vengeance ■ However, when he got close to the Ka’ba with his army, Allah destroyed them by sending birds who pelted them with stones ○ Some suggest this was the year in which the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) was born ● Some of the companions viewed this surah and the one after it (Surah al-Quraysh) as one surah. They would not put Basmallah between them for that reason ○ They both need to be understood together because they complement each other and are connected ■ This surah discusses the security of Mecca and Surah al-Quraysh discusses its prosperity. For any society to prosper, it needs both of these things ○ We need to understand that the safety and prosperity of Mecca was due to the supplication of Ibrahim (pbuh), which he made when he was building the Ka’ba with his son Ismaeel (pbuh) ■ He had asked Allah to make Mecca safe and fill it with all kinds of fruit because it was a barren desert without life. -

Some Notes on Ahl Al-Bayt Shrines in the Early Ṭālibid Genealogies*

Studia Islamica 108 (2013) 1-15 brill.com/si Shared Sanctity: Some Notes on Ahl al-Bayt Shrines in the Early Ṭālibid Genealogies* Teresa Bernheimer University of Oxford This article examines some of the earliest literary evidence for Ahl al-Bayt shrines, contained in the so-called Ṭālibid genealogies. First written in the mid- to late-9th century, nearly contemporaneously with the development of the earliest shrines themselves, these sources were often written by (and perhaps mainly for) the Ahl al-Bayt themselves, providing a picture that the family itself sought to preserve and convey. According to these sources, by the end of the 9th century there clearly were burial places of the Ahl al-Bayt, and especially of the ʿAlid family, that were visited. Such sites were asso- ciated with a number of ʿAlids who were not Shiʿite imams, but “regular” members of the family; thus they were not places of pilgrimage for the Shiʿa only, but sites of veneration that could be shared and even developed regardless of sectarian affiliation. The sites, moreover, became focal points for the Ahl al-Bayt, many of whom settled around them, and came to ben- efit from their waqf arrangements and the pilgrimage “traffic” around them. Over all, the paper argues that the appearance of—or increased attention to—the Ahl al-Bayt shrines from the 9th century onwards had little to do with Shiʿism or Shiʿite patronage; instead, it may be seen as consistent with the wider development of the socio-religious rise of the Ahl al-Bayt: the development of “ʿAlidism”.